1. British-Irish Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Best of the British Isles VIPP July 29

The Best of the British Isles VIPP (England, Scotland, Ireland & Wales! July 29 - Aug. 12, 2022 (14 nights ) on the ISLAND PRINCESS Pauls’ Top Ten List: (Top 10 reasons this vacation is for you! ) 10. You’ll visit 10 ports of call in 4 countries- England, Scotland, Wales & Ireland 9. You & your luggage don’t have to be on a tour bus at 6 a.m each day! 8. You’ll have a lot of fun- Tom & Rita Paul are personally escorting this trip! 7. You & your luggage don’t have to be on a tour bus at 6 a.m each day!! 6. At least 36 meals are included - more, if you work at it! 5. You & your luggage don’t have to be on a tour bus at 6 a.m each day!!! 4. Texas is too hot in August to stay here! 3. You & your luggage don’t have to be on a tour bus at 6 a.m each day!!!! 2. You deserve to see the British Isles (maybe for the second time) in sheer luxury! # 1 reason: You & your luggage don’t have to be on a tour bus at 6 a.m each day!!!!! So, join us! Just think-no nightly hotels, packing & unpacking, we’re going on a real vacation! New ports too! We sail from London (Southampton) to GUERNSEY (St. Peter Port), England- a lush, green island situated near France. CORK (Ireland) allows a chance to “kiss the Blarney stone” as well as enjoy the scenic countryside and villages! On to HOLYHEAD (Wales) then BELFAST (N. -

The Genetic Landscape of Scotland and the Isles

The genetic landscape of Scotland and the Isles Edmund Gilberta,b, Seamus O’Reillyc, Michael Merriganc, Darren McGettiganc, Veronique Vitartd, Peter K. Joshie, David W. Clarke, Harry Campbelle, Caroline Haywardd, Susan M. Ringf,g, Jean Goldingh, Stephanie Goodfellowi, Pau Navarrod, Shona M. Kerrd, Carmen Amadord, Archie Campbellj, Chris S. Haleyd,k, David J. Porteousj, Gianpiero L. Cavalleria,b,1, and James F. Wilsond,e,1,2 aSchool of Pharmacy and Molecular and Cellular Therapeutics, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin D02 YN77, Ireland; bFutureNeuro Research Centre, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin D02 YN77, Ireland; cGenealogical Society of Ireland, Dún Laoghaire, Co. Dublin A96 AD76, Ireland; dMedical Research Council Human Genetics Unit, Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh EH4 2XU, Scotland; eCentre for Global Health Research, Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH8 9AG, Scotland; fBristol Bioresource Laboratories, Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 2BN, United Kingdom; gMedical Research Council Integrative Epidemiology Unit at the University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 2BN, United Kingdom; hCentre for Academic Child Health, Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 1NU, United Kingdom; iPrivate address, Isle of Man IM7 2EA, Isle of Man; jCentre for Genomic and Experimental Medicine, Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University -

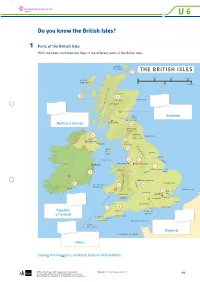

Do You Know the British Isles?

Download (GL 2, U 6, pp. 108–109) 3339a2 U 6 Do you know the British Isles? 1 Parts of the British Isles Fill in the boxes and draw the fl ags of the different parts of the British Isles. SE36834220_British_Isles_GL2.pdfSE36834220_British_Isles_GL2.pdf 1 10.02.2016 1 10.02.2016 10:04:15 10:04:15 O R K N E YO R K N E Y I S L A N D SI S L A N D S 7 THETHE BRITISH BRITISH ISLES ISLES 0 0 100 100 200 200 300 km300 km O U T E R O U T E R H E B R I D E S H E B R I D E S 0 100 EnglandEngland ScotlandScotlandNorthernNorthern Ireland Ireland 0 100 200 miles200 miles s s d d n n InvernessInverness a a l 14 l h h 8 g g Loch Ness AberdeenAberdeen i Loch Ness i H “Union“ JackUnion” Jack” H Ben NevisBen Nevis Firth of Firth of Scotland Forth Forth EdinburghEdinburgh GlasgowGlasgow Northern Ireland 16 EdinburghEdinburgh Castle Castle Hadrian’sHadrian’s 11 NewcastleNewcastle Wall Tyne Giant’s Giant’s Wall Tyne CausewayCauseway Lake Lake BelfastBelfast DistrictDistrict P P e e 12 n I S L E I S L E n n O F O F n i i York York M A N M A N n n e e s s Hull Hull AtlanticAtlantic Ocean Ocean Irish IrishSea Sea 4 6 Humber Humber Galway Galway LiverpoolLiverpool ManchesterManchester DublinDublin 1 Nottingham The SnowdonSnowdon Nottingham The Wash Wash s 9 s Trent Trent n n i i a a t t n n u u o o BirminghamBirmingham Severn Severn M M CambridgeCambridge n 15 St. -

PDF Download a History of the British Isles Prehistory to the Present 1St Edition Pdf Free Download

A HISTORY OF THE BRITISH ISLES PREHISTORY TO THE PRESENT 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kenneth L Campbell | 9781474216678 | | | | | A History of the British Isles Prehistory to the Present 1st edition PDF Book About two to four millennia later, Great Britain became separated from the mainland. Perhaps the most prestigious megalithic monument of Europe is Stonehenge, the stone circle presiding on the rolling hills of Salisbury in Wiltshire, England. The earliest known references to the islands as a group appeared in the writings of seafarers from the ancient Greek colony of Massalia. In: English Heritage. We are independent, we are not part of Britain, not even in geographical terms. In time, Anglo-Saxon demands on the British became so great that they came to culturally dominate the bulk of southern Great Britain, though recent genetic evidence suggests Britons still formed the bulk of the population. English colonialism in Ireland of the 16th century was extended by large-scale Scottish and English colonies in Ulster. Allen, Stephen Lehmberg Request examination copy. However, the terms were never honoured and a new monarchy was installed. Reports on its findings are presented to the Governments of Ireland and the United Kingdom. Section 2 Greek text and English translation at the Perseus Project. The Red Lady of Paviland. The Britons. Request examination copy. In one section, the author explains that the geographic mobility traditionally considered one of the consequences of the 14th- century Black Death actually had begun before the outbreak of the epidemic, as had political discontent among the population, also traditionally attributed to the plague's aftermath. -

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland Is Situated on the British Isles

Дата: 15.10.2020 Группа: 102Фк Специальность: Лечебное дело Тема: The United Kingdom. England. Scotland. Задание лекции: перевести слова под текстом. Домашнее задание – найти: 1) Столицы стран Великобритании 2) Символы стран Великобритании 3) Флаги стран Великобритании 4) Национальные блюда стран Великобритании The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is situated on the British Isles. The British Isles consist of two large islands, Great Britain and Ireland, and about five thousands small islands. Their total area is over 244 000 square kilometres. The United ingdom is one o! the world"s smaller #ountries. Its population is over $% million. &bout '0 (er#ent o! the (o(ulation is urban. The United ingdom is made up of !our #ountries) *ngland, +ales, ,#otland and -orthern Ireland. Their #a(itals are .ondon, /ardi0, *dinburgh and Bel!ast res(e#tivel1. Great Britain #onsists o! *ngland, ,#otland and +ales and does not include -orthern Ireland. But in everyday s(ee#h 2Great Britain» is used in the meaning o! the 2United ingdom o! Great Britain and -orthern Ireland3. The #a(ital o! the U is .ondon. The British Isles are separated from the /ontinent by the -orth ,ea, the *nglish /hannel and the ,trait o! 4over. The western #oast o! Great Britain is washed by the &tlanti# 5#ean and the Irish ,ea. The surface o! the British Isles varies very mu#h. The north o! ,#otland is mountainous and is #alled 6ighlands. The south, whi#h has beauti!ul valleys and plains, is #alled .owlands. The north and west o! *ngland are mountainous, but the eastern, #entral and south-eastern (arts o! *ngland are a vast (lain. -

Offshore Relocations Moving to the Channel Islands the Channel Islands Are a Beautiful and Secure Location Offering an Ideal Base for Families and Businesses

Offshore relocations Moving to the Channel Islands The Channel Islands are a beautiful and secure location offering an ideal base for families and businesses. Offshore relocations Moving to the Channel Islands The traditional arguments made for relocating to the Channel Islands used to revolve around unspoiled beaches, sunshine, great restaurants, golf courses and low tax rates. Today, those arguments still hold As well as the traditional market of Government true – but more and more the retirees, the Channel Islands are relocation agency things that are swaying people drawing more and more towards Jersey and Guernsey are entrepreneurs and people with Locate Jersey saw about the high quality of lifestyle, young families, lured by a 155 inquiries about healthcare and education, strong combination of the lifestyle and high value residency and reliable travel links, a thriving sports on offer, as well as the entrepreneurial culture and the friendly and secure environment, relocations in 2017, availability of quality property. and the infrastructure in terms of and had 31 new travel, health and education inward investment The process of moving offshore services. businesses approved. needs specialist advice, which is why our relocation teams are Navigating through the process of Official figures called in to assist on the residency moving offshore requires expertise process, wealth structuring, and in the residency process itself, the buying property – as well as being process of finding and buying (and From 2016 to 2018, able to guide clients to trusted often extending or adapting) a contacts in the property, tax and property, and in terms of wealth relocation agency banking fields for expert bespoke structuring advice. -

Jersey Location Geography Climate

Jersey Location The Bailiwick of Jersey is located in Europe and has a total area of 45 square miles. Jersey is the largest of the Channel Islands, which are located in the English Channel, off the coast of Normandy, France, and include Guernsey, Alderney, Sark, Herm, and Jethou. Jersey is 9 miles long and 5 miles wide. The island is 14 miles north of France and 100 miles south of Great Britain. It is bordered on the north by the English Channel and on the south by the Bay of Mont St Michel. Its political boundaries also include the reefs of Minquiers and the Ecrehous. (Jones) Geography The geography of the island is mainly gentle and rolling, with rougher hills along the northern coast with the English Channel. The highest point is 143 meters, while sea level is the island’s lowest point. The island’s location in between the Bay of Mont St Michel and the English Channel gives the island tidal ranges of over 40 feet, among the largest range in the world. Most of the island is a plateau which sweeps towards sea level as one travels south. The west end of the island features St Ouen’s Pond, which is Jersey’s largest fresh water source. The interior of the island is home to pastoral grazing lands and home to most of Jersey’s agriculture. Climate Jersey’s climate is quite temperate, due to its location in the English Channel. The island is the sunniest place in the British Isles with an average of over 1,951 hours per year. -

The Union Flag and Flags of the British Isles the Union Flag, Also Known As the Union Jack, Is the National Flag of the United Kingdom

The Union Flag and Flags of the British Isles The Union Flag, also known as the Union Jack, is the national flag of the United Kingdom. It is the British flag. It is called the Union Flag because it stands for the union of the countries of the United Kingdom under one King or Queen. How Was the Union Flag made? The Union Flag is made up of the flags of three of the United Kingdom's countries; the countries of England, of Scotland and of Northern Ireland. England is represented by the flag of its patron saint St. George. The Cross of St. George is a red cross on a white background. Scotland is represented by the flag of its patron saint St. Andrew. The Cross of St. Andrew is a diagonal white cross or saltire on a blue background. In 1603, when King James VI of Scotland became King James I of England, it was a Union of the Crowns, but not of nations. Each country still kept its own parliament. James wanted England and Scotland to be a united kingdom but which flag would be used? The answer was the creation of the first Union Flag. On 12 April 1606, the National Flags of Scotland and England were united for use at sea, making the first Union Jack. The reason for the use of the name ‘Jack’ is not certain. It may have been because the jack was a small flag flown from the jack-staff at a ship’s bow or it may have come from the name of King James. -

Multiple Sclerosis in Island Populations: Prevalence in the Bailiwicks of Guernsey Andj7ersey 23

222Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1995;58:22-26 Multiple sclerosis in island populations: J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.58.1.22 on 1 January 1995. Downloaded from prevalence in the Bailiwicks of Guernsey and Jersey G Sharpe, S E Price, A Last, R J Thompson Abstract ous neurological disability in young adults; it The aim of this study was to establish for affects some 60 000 people in the United the first time the prevalence of multiple Kingdom and perhaps two million people sclerosis in the Bailiwicks of Guernsey worldwide.' The disease shows an unusual and Jersey, as representing the most geographical distribution in becoming com- southerly part of the British Isles. All moner with increasing distance from the patients with multiple sclerosis in the Equator in both the northern and southern Channel Islands resident on prevalence hemispheres.2 There is evidence for a similar day were identified by contacting all geographical gradient in the British Isles.2 medical practices, Multiple Sclerosis, Different studies have reported multiple scle- and Action Research for Multiple rosis to be 1 9 to 3 1 times commoner in Sclerosis societies by letter and visits. women than men and to have a peak age of The crude overall prevalence rates were onset of about 30 years, being rare in child- 1131100 000 (95% confidence interval hood and after the age of 50.2 The clinical fea- (95% CI) 90-3-135.7) and 86-7/100 000 tures, sex ratio, and age specific incidence (95% CI 63.3-110.0) for the Bailiwicks of curves for multiple sclerosis are similar what- Jersey and Guernsey respectively. -

British Isles

British Isles The British Isles are a group of islands off the northwest coast of continental Europe that include the islands of Great Britain and Ireland and over six thousand smaller islands. There are two sovereign states located on the islands: the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (commonly known as the United Kingdom, U.K.) and Ireland (also described as the Republic of Ireland). Great Britain Great Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island. With a population of about 62.5 million people it is the third most populated island on Earth. Great Britain is surrounded by over 1,000 smaller islands. The island of Ireland lies to its west. Great Britain comprises the territory of England, Scotland and Wales and their respective capital cities are London, Edinburgh, and Cardiff. So, the United Kingdom is formed by Great Britain and Northern Ireland; Great Britain is formed by England, Scotland and Wales. Queen Elizabeth II is the head of state of all of them, and London is the capital of England, of Great Britain and of the United Kingdom. The English Channel separates Great Britain from the rest of Europe. The flag The "Union Jack" or "Union Flag" is a composite design made up of three different national symbols, three different flags with different crosses: The cross of St.George, the patron saint of England; The cross of St. Andrews, the patron saint of Scotland; The cross of St. Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland. -

Jersey Fast-Track Procedure to Obtain Jersey Grant

Jersey fast-track procedure to obtain Jersey grant The Probate (Jersey) Law 1998 (as amended) introduced a Upon receipt of the above, we will be required to draft an ‘Fast-Track’ procedure to obtain a Jersey Grant of Probate/ Oath to send for the executors/administrators to sign in the Letters of Administration in estates where the deceased died presence of an authorised witness. Once completed, the Oath domiciled in the British Isles and a corresponding British Grant should be sent back to us and we can then make the of Probate/Letters of Administration has already been application for the Jersey Grant. The Jersey Grant will be issued obtained. The Fast-Track process is therefore only applicable within 3-5 working days of the application having being made. to estates where the deceased died domiciled in England and Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland, Guernsey or the Isle of Man. Our fees for dealing with a Fast-Track estate tend to amount to between £550-£750 with additional fees being charged on a In order to obtain a Jersey Grant, we will require the following: time-costed basis if we are also instructed to deal with the • The original or a Court sealed and certified copy of the collection and distribution of the Jersey assets. British Grant and Will (if the deceased left a Will). If sending Stamp duty is payable to the Jersey Royal Court upon copy documents, please do ensure that both the Will and application for the Jersey Grant at a rate of 0.5% of the date of Grant are separately certified by the Court that issued the death value of the estate (which is rounded up to the nearest original and that each page bears the Court’s seal. -

The British Isles= ______+ ______• the UK = Great Britain + Northern Ireland

• The UK= __________ + _________ • Great Britain= _____ + ________ + ________ • The British Isles= ___________ + __________ • The UK = _Great Britain_ + _Northern Ireland_ • Great Britain = _England_ + _Wales_ + _Scotland_ • The British Isles = _the UK_ + _Ireland_ The UK = Great Britain + Northern Ireland • United Kingdom, island country located off the northwestern coast of mainland Europe. The United Kingdom comprises the whole of the island of Great Britain—which contains England,Wales, and Scotland—as well as the northern portion of the island of Ireland. The capital is London , which is among the world’s leading commercial, financial, and cultural centres. Other major cities include: • Birmingham, Liverpool, and Manchester in England, • Belfast and Londonderry in Northern Ireland, • Edinburgh and Glasgow in Scotland, • Swansea and Cardiff in Wales. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/615557/United-Kingdom Great Britain = England + Wales + Scotland • Great Britain , also known as Britain , is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, off the north-western coast of continental Europe. • It is the ninth largest island in the world and the largest island in Europe. • With a population of about 62 million people in mid- 2010, it is the third most populous island in the world, after Java (Indonesia) and Honshū (Japan). • It is surrounded by over 1,000 smaller islands and islets. • Politically, Great Britain refers to the island together with a number of surrounding islands, which constitute the territory of England, Scotland and Wales. • The island is part of the sovereign state of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, constituting most of its territory: most of England, Scotland and Wales are on the island of Great Britain, with their respective capital cities, London, Edinburgh and Cardiff.