An Ecocritical Approach to Alexandre Hogue's Erosion Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dallas Fine Art Auction 2235 Monitor Street Dallas, TX 75207

Dallas Fine Art Auction 2235 Monitor Street Dallas, TX 75207 Phone: 214-653-3900 Fax: 214-653-3912 January 28, 2012 1/28/2012 LOT # LOT # 1 Alexandre Hogue (1898-1994), "Rattler" lithograph. 5 Edward Dawson-Watson (1893-1978), "Buckin' Steer" Sight: 6.25"H x 11.25"W; Frame: 14''H x tempera on paper board. Image: 5"H x 8.25"W; 18.25''W. Signed and dated lower right, Frame: 11.75"H x 15"W. Signed lower right in "Alexandre Hogue - 1938"; titled and numbered pencil on mat: "Edward Dawson Watson"; titled 13/50 lower left. The theme of man versus lower left in pencil on mat. nature is found in Hogue's paintings during the 800.00 - 1,200.00 1930s. This lithograph of "Rattler" is an excellent example of that. The horseshoe, symbolizing man's presence, and of course the snake being nature. 6 Reveau Bassett (1897-1981), "Ducks" (1) pencil 1,500.00 - 3,000.00 drawing and (1) corresponding etching. Sight: 10"H x 13"W; Frame: 15.25"H x 18.75"W. Signed lower right in pencil, "Reveau Bassett". 1,500.00 - 2,500.00 2 Frank Reaugh (1860-1945), "Untitled" (Creek Scene ) 1896 pastel on paper. Paper: 9.25"H x 4.75"W. Unsigned. A letter of authenticity from Mr. Michael Grauer, Associate 7 Donna Howell-Sickles (b. 1949), "Cowgirls" mixed Director for Curatorial Affairs/Curator for Art, media on canvas. Canvas: 48"H x 48"W; Frame: Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum, Canyon, 49''H x 49''W. -

THE DIGNITY of WORK Exploring Early Texas Art

THE DIGNITY OF WORK Exploring Early Texas Art North Texas Institute for Educators on the Visual Arts Center for the Advancement and Study of Early Texas Art 2005 THE DIGNITY OF WORK Exploring Early Texas Art A Unit of Instruction prepared for The Center for the Advancement and Study of Early Texas Art and The Texas A&M Research Foundation by the North Texas Institute for Educators on the Visual Arts School of Visual Arts University of North Texas 2005 Cover Image: Theodore Gentilz (1819 – 1906), Tamalero, Seller of Tamales, San Antonio, n.d., 7 X 9”, oil, Courtesy of the Witte Museum, San Antonio, Texas Curriculum Developers Lisa Galaviz, M.S. Research Assistant Sarita Talusani, M.Ed. Research Assistant Curriculum Consultants D. Jack Davis, Ph.D. Professor and Director North Texas Institute for Educators on the Visual Arts Jacqueline Chanda, Ph.D. Professor and Chair Division of Art Education and Art History School of Visual Arts University of North Texas Denton, Texas May 2005 This unit of instruction is designed for fourth grade students. Teachers may adapt if for use with other grade levels No part of this unit may be reproduced without the written permission of The North Texas Institute for Educators on the Visual Arts and/or The Center for the Advancement and Study of Early Texas Art THE DIGNITY OF WORK Exploring the Lives of Texans through Early Texas Art The dignity of hard work was and is still a part of the Texas mentality. It is prevalent in the history of Texas, the culture of Texans, and the art that represents the people of Texas. -

Central University Libraries Paid Southern Methodist University Southern Methodist PO Box 750135 University Dallas, Texas 75275-0135

NON-PROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE Central University Libraries PAID Southern Methodist University SOUTHERN METHODIST PO Box 750135 UNIVERSITY Dallas, Texas 75275-0135 Central University Libraries ANNUAL REPORT 2009-2010 CONTENTS YES, WE STILL HAVE BOOKS . But we might also have been occupied by the Lyle School of Clearly these cultural and technological 2 CUL 2.0: Resources for the digital age vooks and Nooks, keitai shousetsu and Engineering for so many years. Stay shifts come with some challenges. 3 Moving forward with generous support gigaku masks, sheriff’s badges and stereo- tuned for exciting developments on our New research suggests that the digital view photographs. From Skype to Swype, library renovation! environment may be fundamentally 4 Collection paints a complete portrait the Central University Libraries are a changing how the human mind acquires This is the brave new world of informa- SMU’s libraries have the best Friends far cry from our grandmothers’ libraries. and retains knowledge. Our librarians 5 tion access – our students want and Our grandmothers would probably be need to anticipate these changes and And the first Literati Award goes to … expect to have it all at the swipe of a mystified by students clustering around are working hard to retool their finger. If they can’t find it quickly on computers or displaying printed pages services. At any given moment, librarians 6 Patricia Van Zandt: Leading a revolution Google, it might just as well not exist. We on electronic readers. Our library is are responding to electronic reference have provided a new “discovery layer,” SMU’s ‘Best Place To Study’ abuzz, and if anyone is saying “shush,” it is questions from around the world, which sits on top of our online catalog the students and not the librarians. -

HETAG: the Houston Earlier Texas Art Group

HETAG: The Houston Earlier Texas Art Group Newsletter, June 2017 Harry Worthman [On the Gulf Coast] 1973, oil on board At the Shore Here it is summer already and for many of us that means it’s time to head for the shore. It meant that for lots of Earlier Houston Artists too, so June seems like a good time to do an At the Shore issue of the Newsletter. There will be Galveston and other Gulf Coast shores, of course, but our artists did a good job of getting around, so there will be quite a few more exotic shores too. Don’t forget to put on your sunscreen. Emma Richardson Cherry Long Beach [California] c.1922, oil on board; Jack Boynton Beach Formation 1953, oil on canvas. HETAG: The Houston Earlier Texas Art Group Eva McMurrey [At the Lake] c. 1959, oil on board Don’t Mess With Texas Art: Tam Kiehnhoff, HETAG member and collector extraordinaire, has done a terrific podcast on the adventures and joys of collecting Texas art, as part of the series “Collecting Culture.” You can hear it here: Collecting Culture – Episode 6: Don’t Mess With Texas Art HETAG Newsletter online (soon): I’m pleased to announce that back issues of the HETAG Newsletter will soon be available online, thanks to our friends at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston’s Hirsch Library. I’m talking about you, Jon Evans, librarian. In fact, they already are available if you’re on the MFAH campus, but plans are to lift that restriction as soon as some technical issues can be addressed. -

THE DALLAS NINE & THEIR CIRCLE: TEXAS ART of the 1930S at TURNER HOUSE

For Immediate Release June 7, 2010 Contact: Russ Aikman, 214-946-3813 THE DALLAS NINE & THEIR CIRCLE: TEXAS ART OF THE 1930s AT TURNER HOUSE The Oak Cliff Society of Fine Arts will hold its annual Wine & Art Fundraiser on Saturday, July 24th at Turner House (401 North Rosemont). We are excited to announce this year’s theme: The Dallas Nine & Their Circle: Texas Art of the 1930s. This show will feature paintings from a small group of influential Texas artists who rejected European tradition and instead created a new style of art intended to capture the realities of everyday life in the southwest during the Great Depression. This is the first show dedicated strictly to The Dallas Nine & Their Circle in the DFW area since a major retrospective was held at the Dallas Museum of Art in 1985. Dr. Sam Ratcliffe, head of the Bywaters Special Collections Wing of the Harmon Arts Library at Southern Methodist University, will speak during a pre-show program about The Dallas Nine and their impact on Texas art. The show is being curated by George Palmer and Konrad Shields, who are Directors of the Texas Art Collectors Association. The exhibition of art in this year’s show will include paintings from numerous Texas artists including Jerry Bywaters, Alexandre Hogue, Everett Spruce and Otis Dozier. The main exhibit opens for viewing at 7PM, along with live music from Western swing band Shoot Low Sherriff, heavy hors d’oeuvres & desserts based on Southern cooking traditions, and regional wine. DATE: Saturday, July 24th LOCATION: Turner House - 401 North Rosemont, Dallas, TX 75208 TIME: 6 – 7PM – Pre-Event Presentation on The Dallas Nine by Dr. -

Unbridled Achievement SMU 2011-12 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE of CONTENTS

UNBRIDLED ACHIEVEMENT SMU 2011-12 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 | SMU BOARD OF TRUSTEES 2011–12 5 | LETTER FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES 6 | SMU ADMINISTRATION 2011–12 7 | LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT 8 | THE SECOND CENTURY CELEBRATION 14 | PROGRESS REPORT Student Quality Faculty and Academic Excellence Campus Experience 38 | FINANCIAL REPORT Consolidated Financial Statements Expenditures Toward Strategic Goals Endowment Report Campaign Update Yearly Giving 48 | HONOR ROLLS Second Century Campaign Donors New Endowment Donors New Dallas Hall Society Members President’s Associates Corporations, Foundations and Organizations Hilltop Society 2 | SMU.EDU/ANNUALREPORT In 2011-12 SMU celebrated the second year of the University’s centennial commemoration period marking the 100th anniversaries of SMU’s founding and opening. The University’s progress was marked by major strides forward in the key areas of student quality, faculty and academic excellence and the campus experience. The Second Century Campaign, the largest fundraising initiative in SMU history, continued to play an essential role in drawing the resources that are enabling SMU to continue its remarkable rise as a top educational institution. By the end of the fiscal year, SMU had received commitments for more than 84 percent of the campaign’s financial goals. Thanks to the inspiring support of alumni, parents and friends of the University, SMU is continuing to build a strong foundation for an extraordinary second century on the Hilltop. SMU BOARD OF TRUSTEES 2011-12 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES Caren H. Prothro, Chair Gerald J. Ford ’66, ’69 Helmut Sohmen ’66 Civic and Philanthropic Leader Diamond A Ford Corporation BW Corporation Limited Michael M. -

DALLAS (SMU) – Jerry Bywaters Cochran, Daughter of Renowned Texas Artist Jerry Bywaters, Has Donated 65 Works of Art to SMU, Including 49 by Jerry Bywaters

GIFT OF TEXAS ART PRESENTED TO MEADOWS MUSEUM Contribution represents one of the largest gifts of art ever presented to the University DALLAS (SMU) – Jerry Bywaters Cochran, daughter of renowned Texas artist Jerry Bywaters, has donated 65 works of art to SMU, including 49 by Jerry Bywaters. The works of art feature a variety of subjects created over the length of Bywaters’ career in media ranging from oils and watercolors to pastels, graphite drawings and prints. Together with a bequest of additional works deeded to the museum, Mrs. Cochran’s contribution represents one of the largest gifts of art presented to the University. “This tremendous gift will enhance the University’s role in preserving the art of this region and will make the Meadows Museum the largest depository of works by Jerry Bywaters, considered one of Texas’ most important artists,” says Mark A. Roglán, director of Meadows Museum. “We are deeply grateful for Mrs. Cochran’s most thoughtful and generous gift.” The gift will become part of SMU’s University Art Collection, which includes Bywaters’ Where the Mountains Meet the Plains (1939), considered one of his greatest landscapes, and will significantly augment the museum’s holdings of Texas regionalist art, Roglán says. The new works of art will be exhibited at Meadows Museum this summer in The Collection of Calloway and Jerry Bywaters Cochran: In honor of a Lone Star Legend, June 3 through August 19, 2012. The art complements the Jerry Bywaters Collection on Art of the Southwest at SMU’s Hamon Arts Library, creating a Jerry Bywaters comprehensive view of the artist’s legacy. -

Artists Active in Texas and Represented in Dallas Museum of Art Collections As of September 2011 for Questions, Contact [email protected] Or 214-922-1277

Artists active in Texas and represented in Dallas Museum of Art Collections as of September 2011 For questions, contact [email protected] or 214-922-1277 Last Name First Name Display Name Nationality and Dates Adams Eleanor Eleanor Adams American, born 1909 Adams Wayman Wayman Adams American, 1883 - 1959 Adickes David David Adickes American, born 1927 Alexander John John Alexander American, born 1945 Allan William William Allan American, born 1936 Allen Terry Terry Allen American, born 1943 Altman Helen Helen Altman American, born 1958 Amado Jesse Jesse Amado American, born 1951 Amerine Wayne Wayne V. Amerine American, born 1928 Arpa y Perea José José Arpa y Perea Spanish, active in America, 1860 - 1952 Austin Dorothy Dorothy Austin American, 1911 - 2011 Avery Eric Eric Avery American, born 1948 Aylsworth David David Aylsworth American, born 1966 Bagley Frances Frances Bagley American, born 1946 Baker David David Baker American, born 1953 Baker Gus Gus Baker American Baker James James Baker American, born 1951 Barber Scott Scott Barber American, 1963 - 2005 Barrera Jose Jose Luis Rivera Barrera American, born 1946 Barsotti Daniel Daniel Barsotti American, born 1950 Bassett Reveau Reveau Bassett American, 1897 - 1981 Bates David David Bates American, born 1952 Batterton Robert Robert E. Batterton American, born 1951 Bearden Edward Edward Bearden American, 1919 - 1980 Bess Forrest Forrest Bess American, 1911 - 1977 Best Rebecca Rebecca Best American, born 1949 Bewley Murray Murray Percival Bewley American, 1884 - 1964 Biggers John John Thomas Biggers American, 1924 - 2001 Black Harding Harding Black American, born 1912 Blackburn Ed Ed Blackburn American, born 1940 Bodycomb Rosalyn Rosalyn Bodycomb American, born 1958 Bomar Bill Bill Bomar American, born 1919 Boshier Derek Derek Boshier British, born 1937 Bowling Charles Charles T. -

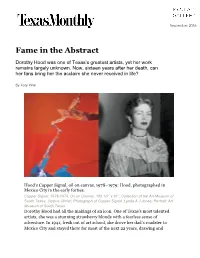

Fame in the Abstract

September 2016 Fame in the Abstract Dorothy Hood was one of Texas’s greatest artists, yet her work remains largely unknown. Now, sixteen years after her death, can her fans bring her the acclaim she never received in life? By Katy Vine Hood’s Copper Signal, oil on canvas, 1978–1979; Hood, photographed in Mexico City in the early forties. Copper Signal, 1978-1979, Oil on Canvas, 109 1/2” x 81”; Collection of the Art Museum of South Texas, Corpus Christi; Photograph of Copper Signal: Lynda A J Jones; Portrait: Art Museum of South Texas Dorothy Hood had all the makings of an icon. One of Texas’s most talented artists, she was a stunning strawberry blonde with a fearless sense of adventure. In 1941, fresh out of art school, she drove her dad’s roadster to Mexico City and stayed there for most of the next 22 years, drawing and painting alongside Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Roberto Montenegro, and Miguel Covarrubias. Pablo Neruda wrote a poem about her paintings. José Clemente Orozco befriended and encouraged her. The Bolivian director and composer José María Velasco Maidana fell hard for her and later married her. And after a brief stretch in New York City, she and Maidana moved to her native Houston, where she produced massive paintings of sweeping color that combined elements of Mexican surrealism and New York abstraction in a way that no one had seen before, winning her acclaim and promises from museums of major exhibits. She seemed on the verge of fame. “She certainly is one of the most important artists from that generation,” said art historian Robert Hobbs. -

HETAG: the Houston Earlier Texas Art Group

HETAG: The Houston Earlier Texas Art Group Jack Boynton Sunstone 1957, mixed media on canvas, 44 x 77 in. a magnificent painting from Boynton’s prime, at Foltz Fine Art. HETAG Newsletter No. 36, August 2019 This issue of the HETAG Newsletter is filled with a variety of things to provide some Earlier Houston Art diversion during the long, hot August days when it’s too late to get a plane to cooler places, and too early to nap or drink. There is news of a great little show at MFAH celebrating the art savvy and philanthropy of Miss Ima Hogg, and a rediscovered travelogue by two Houstonians in Europe in 1949; notice of an upcoming show focusing on Modernism in Houston and Dallas in the 1930s, and an invitation to float down the Seine with other HETAGers on a river cruise in 2020. Maybe you’ll find something to take your mind off the weather, and remind you that good times with Houston art are in your future. John T. Biggers History of Education in Morris County, Texas 1954/55, casein on muslin, 5.5 x 22 ft., one of the magnificent works by Houston artists on view at the Witte Museum. HETAG: The Houston Earlier Texas Art Group Off to Europe, 1949! Part 1 of a travelogue wherein Houstonians Gene Charlton (1909-1979) and Jon Chaudier (1921-?) set out for a year in Europe (France, Italy, Spain and Morocco) – serialized weekly in the pages of the Houston Post from May 1949 to March 1950 – recently rediscovered in the digitized version of the newspaper, available at Rice University Library. -

READ ME FIRST Here Are Some Tips on How to Best Navigate, find and Read the Articles You Want in This Issue

READ ME FIRST Here are some tips on how to best navigate, find and read the articles you want in this issue. Down the side of your screen you will see thumbnails of all the pages in this issue. Click on any of the pages and you’ll see a full-size enlargement of the double page spread. Contents Page The Table of Contents has the links to the opening pages of all the articles in this issue. Click on any of the articles listed on the Contents Page and it will take you directly to the opening spread of that article. Click on the ‘down’ arrow on the bottom right of your screen to see all the following spreads. You can return to the Contents Page by clicking on the link at the bottom of the left hand page of each spread. Direct links to the websites you want All the websites mentioned in the magazine are linked. Roll over and click any website address and it will take you directly to the gallery’s website. Keep and fi le the issues on your desktop All the issue downloads are labeled with the issue number and current date. Once you have downloaded the issue you’ll be able to keep it and refer back to all the articles. Print out any article or Advertisement Print out any part of the magazine but only in low resolution. Subscriber Security We value your business and understand you have paid money to receive the virtual magazine as part of your subscription. Consequently only you can access the content of any issue. -

Danville Chadbourne West Texas Triangle

DANVILLE CHADBOURNE WEST TEXAS TRIANGLE THE TRANSIENT PERMANENCE OF THE AUSPICIOUS MOMENT 1996 Museum of the Southwest Front Cover THE INEVITABLE QUESTION 2007-10 Ellen Noël Art Museum DANVILLE CHADBOURNE WEST TEXAS TRIANGLE 2013 THE GRACE MUSEUM Abilene, Texas May 30 – August 15 THE OLD JAIL ART CENTER Albany, Texas June 1 – September 1 ELLEN NOËL ART MUSEUM Odessa, Texas June 7 – August 25 MUSEUM OF THE SOUTHWEST Midland, Texas June 7 – August 25 SAN ANGELO MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS San Angelo, Texas July 5 – September 1 THE SPACE FOR ART In January of 2006, Marilyn Bassinger, then director of the Ellen Noël Art Museum in Odessa, called together colleagues from four other art museums in West Texas to explore possible collaborations for The Year of the Museum, a loosely themed program that the American Association of Museums was promoting for 2006. Although all thought it a worthy idea, the directors agreed that even beginning in January, they were behind the curve to accomplish something for 2006. Instead, they began to talk about other ways to collaborate—especially in marketing institutions that are distant from metropolitan centers and widely spread in an area the size of Ohio. Four of the museums were accredited (and the fifth subsequently gained accreditation), marking them among the most elite in the nation. Each knew it was serving its own community superbly, but all wanted to reach wider audiences. With small individual marketing budgets, these museums reasoned they could have a bigger impact trumpeting themselves collectively. The museums were: The Ellen Noël Museum of the Permian Basin, Odessa; The Grace Museum, Abilene; the Museum of the Southwest, Midland; the Old Jail Art Center, Albany; and the San Angelo Museum of Fine Arts, San Angelo.