How Safe and Inclusive Are Otago Secondary Schools?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2015

Annual Report 2015 1 2015 Netball South Annual Report Netball South Board Members Contents Board Members, Staff & Life Members . 1 Chairman’s Report . 2 Chief Executive’s Report . 3 Ascot Park Hotel Southern Steel . 5 Sponsors and Funding . 7 Netball South board members (from left) Kerry Seymour, Paul Buckner Performance Programme (Chair), Angee Shand, Adrienne Ensor, Alastair McKenzie and Colin Weatherall (NNZ delegate). Report . 9 Community Netball Netball South Staff Members Manager’s Report . 11 Lana Winders Chief Executive Officer Umpire Development Sue Clarke Chief Executive Officer (until February 2015) Rosie De Goldi Community Netball Manager Report . 14 Kate Buchanan Corporate and Communications Manager Jo Morrison Performance Manager (until August 2015) Competitions . 16 Jan Proctor Office Manager Sonya Fleming Event Manager Honours and Carla O’Meara Marketing and Event Coordinator Achievements . 18 Colleen Bond Umpire Development Officer Brooke Morshuis Otago Development Officer Statement of Accounts . 21 Hannah Coutts Southland Development Officer Paula Kay-Rogers Central Development Officer Netball South Life Members Listed below are the combined life members of Netball Otago and Netball Southland which have been transferred into Netball South Mrs J Barr^, Ngaire Benfell, Margaret Bennie, Mrs C Bond MNZM, Yvonne Brew, Mrs R Broughton ONZM+, Ms K Brown, Mrs V Brown+, Margaret Bruss, Mrs M Burns ONZM+, Norma Burns, Violet Byers, Lyn Carwright, Ann Conder, Mrs O Crighton^, Joan Davey, Pauline Dodds, Mrs S Faithful+, Liz Farquhar, -

The New Zealand Gazette 443

H MARCH THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 443 $ $ The Duke of Edinburgh's Award in New Zealand ...... 200 N.Z. Foundation for the B1ind----Oamaru Advisory Otago Gymnastic Association 300 Committee ...... ...... ...... ..... ...... 50 Dynex Gymnastic Club (Inc.) 100 Salvation Army Advisory Trust Board, Glenside Lodge 50 Ralph Ham Park 100 Kurow Scout and Guide Building Committee 50 The Navy League Otago (N.Z.) Inc. 200 Balclutha Branch of the Plunket Society ...... 100 Otago Youth Adventure Trust Inc. 1,000 St. John Ambulance Association, South Otago 300 Pleasant Valley Baptist Trust Board 200 Scout Association of N.Z., Clutha District ...... 200 Waianakarua Youth Camp 100 Kaitangata Scout Group ...... ...... 50 Wesleydale Camp 200 Girl Guides Association Clutha District Committee Otago Presbyterian Campsites Committee 100 Shepard Campsite Fund ...... ...... 200 Youth Hostels Association of N.Z., Dunedin Branch 200 Balclutha Swimming and Surf Life-saving Club 100 Y.W.C.A. 500 Kaitangata Baths Appeal Committee ...... ...... 100 Y.M.C.A. 400 Balclutha Primary School Parent Teachers Association 200 King's High School Parents Association Inc. 400 Warepa Home and School Association 50 King Edward Techn1ical High School Parent Teacher Waiwera South School Committee 50 Association ..... 200 Clinton Play Centre 50 Andersons Bay School Committee 100 Owaka Play Centre ...... ...... 50 Tomahawk School and Ocean Grove District Baths P.S.S.A. on behalf of Holmdene Home 200 Committee ..... 100 South Otago Histori'cal Society ...... ...... 50 East Otago High School Parent Teacher Association ..... 200 Catlins Historical Society ...... ...... 50 Assumption Convent 400 Alexandra Sub-branch of the Plunket Society 100 Little Sisters of the Poor 400 Clyde Sub-branch of the Plunket Society ..... -

2019 National School Downhill Results.Pdf

CYCLING NZ SCHOOLS 2019 NATIONAL MOUNTAIN BIKE CHAMPIONSHIPS - PRESENTED BY EVO CYCLES FOX DOWNHILL RESULTS SIGNAL HILL, DUNEDIN Saturday 5 October UNDER 20 BOYS PLACE NAME SURNAME # FROM TIME GAP OVERALL PL- SEEDING 1 Albert Snep 416 Scots College 3:19.13 +0:00.00 1 2- 3:36.51 2 Todd Ballance 354 Nelson College 3:20.44 +0:01.31 2 1- 3:34.48 3 Indy Hawthorne 421 Shirley Boys High School 3:24.94 +0:05.81 3 4- 3:47.68 4 Luke Gill 399 Rangiora High School 3:27.07 +0:07.94 4 5- 3:50.56 5 Jordan Sutherland 430 Shirley Boys High School 3:36.23 +0:17.10 9 8- 4:00.56 6 Harlen Hancock 206 Dunstan High School 3:37.33 +0:18.20 11 7- 3:57.76 7 Zac Pearson 231 Fiordland College 3:39.41 +0:20.28 12 10- 4:11.13 8 Max Taylor 393 Palmerston North Boys High School 3:41.63 +0:22.50 16 6- 3:53.35 9 Elliot Wareing 182 Christchurch Boys High School 3:43.63 +0:24.50 20 20- 4:48.70 10 Lui Arnold 283 Lincoln High School 3:43.67 +0:24.54 22 24- 5:25.72 11 Ethan Burns 454 St Patrick's College, Silverstream 3:44.82 +0:25.69 28 9- 4:01.94 12 Connor Leov 357 Nelson College 3:49.16 +0:30.03 33 14- 4:20.42 13 Joshua Bryant 449 St Kevin's College 3:49.79 +0:30.66 34 11- 4:11.44 14 Joshua Pearson 230 Fiordland College 3:52.70 +0:33.57 36 23- 5:14.10 15 Dominic Sutherland 489 Verdon College 3:56.64 +0:37.51 42 16- 4:23.34 16 Angus Moody 391 Palmerston North Boys High School 3:57.38 +0:38.25 43 19- 4:48.57 17 Jack Murray 255 John McGlashan College 4:02.84 +0:43.71 52 12- 4:12.58 18 Will Morshuis 254 John McGlashan College 4:03.72 +0:44.59 54 17- 4:33.30 19 Ned Hudson 336 -

Become Part of Our Story YOUR STORY BEGINS Welcome

Become part of our story YOUR STORY BEGINS Welcome Haere mai ki te Welcome to Columba College, where our aim is tohatoha tō korero to instil in every student a love of learning and an understanding that education matters. For over ki a mātou, kei reira a century, we have been preparing students to contribute and succeed, wherever their path may koe tau ai. take them. Columba is unique. A state-integrated, special character school, it is co-educational from years 0-6, and then Come and share offers single sex girls’ education and boarding from your story with us, years 7-13. Founded as a Presbyterian school in 1915, the and find the place Presbyterian faith has long been associated with where you belong. education, and service within the community. In an inclusive environment, students are taught to respond generously and compassionately, and to look after one another and those within their community. At Columba we have a clear academic focus and encourage excellence in sport and cultural pursuits, while being mindful of each student's wellbeing. Pauline Duthie We teach our students to think creatively and critically Principal in all aspects of their lives and to know that each and everyone of them can make a difference. 2 3 MISSION STATEMENT With grace and good discipline, we are dedicated to all Columba College students being lifelong learners committed to personal excellence, ethical behaviour and service to others. 4 VALUES AND MISSION Our History Columba was founded in 1915, the amalgamation of two earlier girls’ schools, Girton College and Braemar House School. -

Secondary Schools of New Zealand

All Secondary Schools of New Zealand Code School Address ( Street / Postal ) Phone Fax / Email Aoraki ASHB Ashburton College Walnut Avenue PO Box 204 03-308 4193 03-308 2104 Ashburton Ashburton [email protected] 7740 CRAI Craighead Diocesan School 3 Wrights Avenue Wrights Avenue 03-688 6074 03 6842250 Timaru Timaru [email protected] GERA Geraldine High School McKenzie Street 93 McKenzie Street 03-693 0017 03-693 0020 Geraldine 7930 Geraldine 7930 [email protected] MACK Mackenzie College Kirke Street Kirke Street 03-685 8603 03 685 8296 Fairlie Fairlie [email protected] Sth Canterbury Sth Canterbury MTHT Mount Hutt College Main Road PO Box 58 03-302 8437 03-302 8328 Methven 7730 Methven 7745 [email protected] MTVW Mountainview High School Pages Road Private Bag 907 03-684 7039 03-684 7037 Timaru Timaru [email protected] OPHI Opihi College Richard Pearse Dr Richard Pearse Dr 03-615 7442 03-615 9987 Temuka Temuka [email protected] RONC Roncalli College Wellington Street PO Box 138 03-688 6003 Timaru Timaru [email protected] STKV St Kevin's College 57 Taward Street PO Box 444 03-437 1665 03-437 2469 Redcastle Oamaru [email protected] Oamaru TIMB Timaru Boys' High School 211 North Street Private Bag 903 03-687 7560 03-688 8219 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TIMG Timaru Girls' High School Cain Street PO Box 558 03-688 1122 03-688 4254 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TWIZ Twizel Area School Mt Cook Street Mt Cook Street -

Terranet - Property Information Online

Street Address: 28 Columba Avenue, Calton Hill, Dunedin Zoned Schools for this Property Primary / Intermediate Schools LIBERTON CHRISTIAN SCHOOL 6.7 km Secondary Schools COLUMBA COLLEGE 4.4 km JOHN MCGLASHAN COLLEGE 5.3 km KAVANAGH COLLEGE 3.6 km KINGS HIGH SCHOOL (DUNEDIN) 2.4 km ST HILDAS COLLEGIATE 4.5 km Early Childhood Education Concord Kindergarten 93 Mulford Street Distance: 0.8 km Concord 20 Hours Free: Yes Dunedin Type: Free Kindergarten Ph. 03-4876704 Authority: Community Based Corstorphine Kindergarten 10 Lockerbie Street Distance: 1.4 km Dunedin 20 Hours Free: Yes Ph. 03-4878295 Type: Free Kindergarten Authority: Community Based Richard Hudson Kindergarten 42 Rutherford Street Distance: 1.4 km Caversham 20 Hours Free: Yes Dunedin Type: Free Kindergarten Ph. 03-4558565 Authority: Community Based Riselaw Road Playcentre 38 Riselaw Road Distance: 0.2 km Corstorphine 20 Hours Free: No Dunedin Type: Playcentre Ph. 03-4876847 Authority: Community Based Tino- E-Tasi Preschool 10 Stenhope Crescent Distance: 1.3 km Corstorphine 20 Hours Free: Yes Dunedin Type: Education & Care Service Ph. 03-4877522 Authority: Privately Owned Primary / Intermediate Schools BALACLAVA SCHOOL 2 Mercer Street Distance: 1.0 km Balaclava Decile: 8 Dunedin Age Range: Contributing Ph. 03 488 4667 Authority: State Gender: Co-Educational School Roll: 199 Zoning: Out of Zone Report Date: 03 Nov 2019 Source: Terranet - Property Information Online. http://www.terranet.co.nz/ Page 1 of 4 CONCORD SCHOOL 5 Thoreau Street Distance: 1.0 km Concord Decile: 4 Dunedin Age Range: Contributing Ph. 03 488 2204 Authority: State Gender: Co-Educational School Roll: 134 Zoning: No Zone Carisbrook School 217 South Road Distance: 1.5 km Caversham Decile: 3 Dunedin Age Range: Full Primary Ph. -

Team Registrations.Xlsx

Dunedin Netball Y7/8 Competition Festival Game Play R1 Game Play R2 School Game Play Courts* Pod 4.10pm 4.21pm Balmacewen Intermediate Balmac Yellow 5 5 Tahuna Normal Intermediate Tahuna 7A 5 9 A: 3.30pm Taieri College Taieri College Comets 9 5 Balmacewen Intermediate Balmac Grey 9 9 Bathgate Park School BGP Coyotes 8 8 Green Island School Green Island Steel 8 10 B: 3.30pm Kaikorai Valley College Whero 10 8 Liberton Christian School Liberton Gold 10 10 Balmacewen Intermediate Balmac Gold 11 11 Columba College Columba 8A 11 13 C: 3.30pm Taieri College Taieri College Tactix 13 11 Taieri College Taieri College Steel 13 13 Columba College Columba 7A 12 12 Kavanagh College Kavanagh 7 Gold 12 14 D: 3.30pm Tahuna Normal Intermediate Tahuna 7B 14 12 Balmacewen Intermediate Balmac Orange 14 14 Arthur Street School Arthur Street Steel 15 15 Kavanagh College Kavanagh 7/8 Blue 15 17 Kaikorai Valley College Kowhai 16 16 E: 3.30pm Portobello School Baybellos 16 15 Kavanagh College Kavanagh 7/8 Gold 17 17 Dunedin Rudolf Steiner School Steiner Salts 17 16 Balmacewen Intermediate Balmac Maroon 19 19 Kaikorai Valley College Matai 19 21 F: 3.30pm Bathgate Park School BGP Hyenas 21 19 Fairfield School (Dunedin) Fairfield Steel 21 21 *Please note teams go to these courts after completing the Dunedin Netball led NetballSmart Warmup. After 8mins they play another team from their pod. Dunedin Netball Y7/8 Competition Festival Game Play R1 Game Play R2 Game Play R3 School Game Play Courts* Pod 5.10pm 5.21pm 5.33pm Balmacewen Intermediate Balmac Silver 5 5 Dunedin -

South Island Championship Dunedin

Draw for South Island Championship 31st August - 4th September, Dunedin Boys Girls Pool A Pool B Pool A Pool B Dunstan High School Toko-LAS Waitaki Girls High School St Peters College, Gore Geraldine High School Lincoln High School Cromwell College St Kevins College Riccarton High School Roncali College Timaru Girls High School Otago Girls High School St Peters College, Gore St Kevins College Cromwell College Shirley Boys High School John McGlashan College 2XI Taieri College Pool C Pool D Marian College Kaipoi High School Dunstan High School Roncali College Riccarton High School Taieri College St Hildas Collegiate 2XI Rangi Ruru Girls School 2XI Monday 31st August 2020 Round 1 & 2 Team A Team B Pool Turf 8:00am Marian College V St Hildas Collegiate 2XI Girls C OPT 8:00am Dunstan High School V Riccarton High School Girls C LFT 9:00am Cromwell College V Timaru Girls High School Pool A OPT 9:00am Kaipoi High School V Rangi Ruru Girls School 2XI Pool D LFT 10:00am Waitaki Girls High School V St Peters College , Gore Girls A/B NON COMP OPT 10:00am St Kevins College V Otago Girls High School Pool B LFT 11:00am Roncali College V Taieri College Pool D OPT 11:00am Dunstan High School V John Mcglashan College 2XI Boys A LFT 12:00pm Geraldine High School V Cromwell College Boys A OPT 12:00pm Riccarton High School V St Peters College , Gore Boys A LFT 1:00pm Toko - LAS V Taieri College Boys B OPT 1:00pm Lincoln High School V Shirley Boys High School Boys B LFT 2:00pm Roncali College V St Kevins College Boys B OPT 2:00pm Marian College V Riccarton -

2021 Evo Cycles Otago Southland Secondary School Mtb Championships Cross Country Results Sunday 21 February

2021 EVO CYCLES OTAGO SOUTHLAND SECONDARY SCHOOL MTB CHAMPIONSHIPS CROSS COUNTRY RESULTS SUNDAY 21 FEBRUARY UNDER-13 BOYS PLACE NAME # SCHOOL TIME TIME+ LAP-1 LAP-2 LAP-3 1 Samuel Lawrence 67 Southland Boys High 0:35:30 +0:00:00 1- 0:11:58 1- 0:11:28 1- 0:12:04 2 Daniel Grieve 64 John Mcglashan College 0:37:20 +0:01:50 2- 0:12:32 2- 0:12:21 2- 0:12:27 3 Ryan McRitchie-King 69 Halfmoon Bay School 0:37:47 +0:02:17 4- 0:12:56 3- 0:12:30 3- 0:12:21 4 Oscar Chapman 60 St Marys School 0:38:44 +0:03:14 3- 0:12:34 4- 0:12:56 4- 0:13:14 5 Hunter Dobson 62 St Marys School 0:38:46 +0:03:16 5- 0:13:00 5- 0:12:32 5- 0:13:14 6 Quinn Moffat 70 Fiordland College 0:42:21 +0:06:51 6- 0:13:50 6- 0:13:20 6- 0:15:11 7 Xavia Hurring 66 Dundin North Intermediate 0:48:56 +0:13:26 7- 0:16:28 7- 0:15:55 7- 0:16:33 UNDER-13 GIRLS PLACE NAME # SCHOOL TIME TIME+ LAP-1 LAP-2 LAP-3 1 Paige Adams 10 The Terrace Primary School 0:37:56 +0:00:00 1- 0:12:58 1- 0:12:21 1- 0:12:37 UNDER-14 BOYS PLACE NAME # SCHOOL TIME TIME+ LAP-1 LAP-2 LAP-3 LAP-4 1 Cam Moir 87 Dunstan High School 0:43:11 +0:00:00 1- 0:10:41 1- 0:10:37 1- 0:11:07 1- 0:10:46 2 William Miller 86 Dunstan High School 0:47:21 +0:04:10 5- 0:12:50 4- 0:11:36 3- 0:11:37 2- 0:11:18 3 Elijah Le 83 Balmacewen 0:47:44 +0:04:33 2- 0:11:50 2- 0:11:49 2- 0:12:15 3- 0:11:50 4 Liam Rasmussen 88 Queenstown Primary School 0:48:53 +0:05:42 3- 0:12:11 3- 0:11:52 4- 0:12:05 4- 0:12:45 5 Jakob Dobson 82 Kings High School 0:51:01 +0:07:50 4- 0:12:30 5- 0:12:20 5- 0:13:00 5- 0:13:11 6 Charlie Byrne 80 Fiordland College 0:53:15 +0:10:04 -

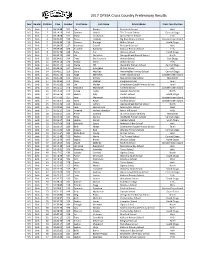

2017 OPSSA Cross Country Preliminary Results

2017 OPSSA Cross Country Preliminary Results Year Gender Position Time Number First Name Last Name School Name Cross Country Zone Yr5 Girls 1 08:59.88 161 Lila Rhodes Portobello School Ariki Yr5 Girls 2 09:14.10 143 Summer Liddell The Terrace School Central Otago Yr5 Girls 3 09:18.68 131 Molly Goldsmith Arthur Street School Hills Yr5 Girls 4 09:22.45 129 Tessa Gabbott Big Rock Primary School Greater Green Island Yr5 Girls 5 09:26.49 110 Gemma Burleigh Milton School South Otago Yr5 Girls 6 09:28.00 117 Kotomiyo Cowell Portobello School Ariki Yr5 Girls 7 09:29.56 106 Anabelle Batchelor Kaikorai Primary School Hills Yr5 Girls 8 09:31.78 128 Ruby Fox Weston school North Otago Yr5 Girls 9 09:33.72 159 Isla Nicholson George Street Normal School North Yr5 Girls 10 09:34.81 124 Freya Des Fountain Waitati School East Otago Yr5 Girls 11 09:36.14 176 Hayley Ward Wakari School Hills Yr5 Girls 12 09:37.17 134 Madie Hill Alexandra Primary School Central Otago Yr5 Girls 13 09:38.14 127 Jasmyn Evangelou St Clair School Ariki Yr5 Girls 14 09:40.01 150 Siena Mackley Remarkables Primary School Central Otago Yr5 Girls 15 09:45.78 156 Paige Merrilees Green Island School Greater Green Island Yr5 Girls 16 09:47.40 141 Nicola Kinney Maniototo Area School Maniototo Yr5 Girls 17 09:49.88 179 Olivia Webber Elmgrove School Taieri Yr5 Girls 18 09:50.93 189 Lily Walker Silverstream South Primary School Taieri Yr5 Girls 19 09:52.11 148 Michaela MacDonell Fairfield School Greater Green Island Yr5 Girls 21 09:54.19 173 Aimee Taylor Sawyers Bay School North Yr5 Girls -

Newsletter 3 Community Notices

11 13September March 2020 2020 NEWSLETTERNEWSLETTER 8 3 13 - 14 September - OSS Netball Promoting academic excellence is an ongoing focus for our Board and staff. We have recently created an Academic Honours Board celebrating students 17 September - BoT Student who have achieved Excellence Endorsements in their NCEA. We have also Election voting closes midday awarded badges for Merit Endorsement for the first time this year. I commend the initiative by prefect Daniel Helms who is establishing an Academic 18 September - Staff Only Day Committee so that students are enabled to take a lead with this focus. The draft vision and mission of this group are: 23 September - CO Volleyball Tournament Vision Dance Workshops Creating a culture where academic pursuit and excellence is aspired to 25 September - SIT Open Day and valued by all in our school community. Mission 25 September - Last Day Students leading, inspiring and encouraging their fellow students to of Term Three excel academically through the promotion, celebration and support for 12 October - First Day academic endeavour within our kura. of Term Four Students have self nominated and the committee aims to meet before the end of this term. 17 October - School Ball Tamara Hansen has given so much and gained so much 20 - 21 October - Year 10 from her dedicated service to St John Youth over the past 10 Exam period years. To have been named the South Island Regional Cadet of the Year is a huge honour and fitting recognition for 26 October - Labour Day her mahi. I know that she is excited to be supporting, 5 November - Last day of encouraging and inspiring other cadets across Te Wai school for Years 11-13, Senior Pounamu (South Island) when she starts her role next year. -

SI Info 1 for 2003

SOUTH ISLAND SECONDARY SCHOOLS' ATHLETIC CHAMPIONSHIPS Information One DATE: Saturday 29th – Sunday 30th March 2003 TIME: Commencing at 8:45am VENUE: Trafalgar Park, Trafalgar St, Nelson COST: As this event is not yet sponsored. An entry fee or gate admission may need to apply to all competitors, school officials, spectators and supporters. ENTRY: Is through Regional Selectors only. Entry forms will be sent to these once notice as to who they are has been received. Entries must be received by 5pm on Monday 24th March 2003. ACCOMMODATION: Accommodation for all teams has been reserved at a variety of places in Nelson by Nelson Tourism Service. Prices range between $15-$40 Per person per night, depending on type of accommodation. Bookings are easy, simply fill in the booking form which will be sent out to all schools with the registration packs in February. For further information contact the accommodation co-ordinators Nelson Tourism Services on 03 –546 6338 or email [email protected]. ORGANISATIONAL TIMELINE: January 22nd Wednesday Preliminary information distributed through Regional Sports Directors February 7th Friday Information one sent to all eligible South Island Schools March 24th Monday Entries close at 5pm March 28th Friday AGM of SI Athletics Teachers Association. Manager’s packs distributed. March 29th – 30th Sat/Sun SISS Athletic Championship, Trafalgar Park, Nelson This mailing includes: 1 Notice of Managers Meeting & Annual General Meeting (Information packs available at this meeting) 2 Information for competitors (specifications & notes ) 3 List of potential competing schools (with the 4 letter code and uniform) (If this information is incorrect, please fax corrected information to Westpac Tasman Sports Director, fax: 03546 3300.