The Original Pinettes and Black Feminism in New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mount Shasta Annotated Bibliography Chapter 18

Mount Shasta Annotated Bibliography Chapter 18 Legends: Other This section contains a number of unrelated entries, including material about the oft-mentioned bell legends, the little people legends, and UFO legends. Some miscellaneous entries, arguably termed legends, include an entry about two Alaskan mountains named for Mt. Shasta, and an entry for the 1930s' slang phrase "From Mt. Shasta." Some of the materials exhibit a rare originality, especially Caroling's comic-book styled Mount Shasta and the Galaxy People. This section also includes a number of miscellaneous entries which in one way or another convey the mystic and spiritual expectations of some visitors to Mt. Shasta. The [MS number] indicates the Mount Shasta Special Collection accession numbers used by the College of the Siskiyous Library. [MS2156]. Avenell, Bruce K. Mount Shasta: The Vital Essence, A Spiritual Explorers Guide. Escondido: Eureka Society, 1999. 154 pp. Subtitle: To the Natural and Man-Made Consciousness-Enhancing Structures on Mt. Shasta The author recounts spiritual lessons and experiences from several decades of travel to Mount Shasta. Sand Flat, Grey Butte, Panther Meadows, etc, are described as special places. The author has a spiritual communication with a spiritual being named Duja, on Mt. Shasta and elsewhere. The book begins: 'A small group of very dedicated people, The Eureka Society has been coming to Mt. Shasta, California, for thirty years. They come to communicate with a spiritual being with whom many of them have had spiritual experiences while camping, hiking, and meditating on the mountain.' (p. ix). 'Although Duja, or any of the spirit beings on the mountain for that matter, may appear to be standing still she must have complete control of attitude, conscious focus, mental velocity and be monitoring the expenditure of energy necessary for you to see her. -

Navigating Jazz: Music, Place, and New Orleans by Sarah Ezekiel

Navigating Jazz: Music, Place, and New Orleans by Sarah Ezekiel Suhadolnik A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Musicology) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Chair Professor David Ake, University of Miami Associate Professor Stephen Berrey Associate Professor Christi-Anne Castro Associate Professor Mark Clague © Sarah Ezekiel Suhadolnik 2016 DEDICATION To Jarvis P. Chuckles, an amalgamation of all those who made this project possible. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation was made possible by fellowship support conferred by the University of Michigan Rackham Graduate School and the University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities, as well as ample teaching opportunities provided by the Musicology Department and the Residential College. I am also grateful to my department, Rackham, the Institute, and the UM Sweetland Writing Center for supporting my work through various travel, research, and writing grants. This additional support financed much of the archival research for this project, provided for several national and international conference presentations, and allowed me to participate in the 2015 Rackham/Sweetland Writing Center Summer Dissertation Writing Institute. I also remain indebted to all those who helped me reach this point, including my supervisors at the Hatcher Graduate Library, the Music Library, the Children’s Center, and the Music of the United States of America Critical Edition Series. I thank them for their patience, assistance, and support at a critical moment in my graduate career. This project could not have been completed without the assistance of Bruce Boyd Raeburn and his staff at Tulane University’s William Ransom Hogan Jazz Archive of New Orleans Jazz, and the staff of the Historic New Orleans Collection. -

Black Pearls

Number 22 The Journal of the AMERICAN BOTANI CAL COUNCU.. and the HERB RESEARCH FOUNDATION Hawthorn -A Literature Review Special Report: Black Pearls - Prescription Drugs Masquerade as Chinese Herbal Arthritis Formula FROM THE EDITOR In This Issue his issue of HerbalGram offers some good news and some herbal combination for use in rheumatoid arthritis and related bad news. First the good news. Our Legal and Regulatory inflammatory conditions, this product has been tested repeatedly Tsection is devoted to a recent clarification by the Canadian and shown positive for the presence of unlabeled prescription drugs. Health Protection Branch (Canada's counterpart to our FDA)of its Herb Research Foundation President Rob McCaleb and I have willingness to grant "Traditional Medicine" status to many medici spent several months researching the latest resurgence in sales of nal herb products sold in Canada under the already existing approval this and related products. We have made every attempt to follow up process for over-the-counter remedies. This announcement has on many avenues to determine whether these products contain un been hailed as a positive step by almost everyone with whom we labeled drugs, and whether or not they are being marketed fraudu have talked, both in academia and in the herb industry. lently. Herb marketers and consumers alike should be concerned More good news is found in the literature review on Hawthorn. whenever prescription drugs are presented for sale as "natural" and Steven Foster has joined Christopher Hobbs in preparing a compre "herbal." You will find our report on page 4. hensive view of a plant with a long history of use as both food and In addition, we present the usual array of interesting blurbs, medicine. -

Japan Loves New Orleans's Music

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Senior Honors Theses Undergraduate Showcase 5-2017 Nihon Wa New Orleans No Ongaku Ga Daisukidesu (Japan Loves New Orleans’s Music): A Look at Japanese Interest in New Orleans Music from the 1940s to 2017 William Archambeault University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/honors_theses Part of the Oral History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Archambeault, William, "Nihon Wa New Orleans No Ongaku Ga Daisukidesu (Japan Loves New Orleans’s Music): A Look at Japanese Interest in New Orleans Music from the 1940s to 2017" (2017). Senior Honors Theses. 94. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/honors_theses/94 This Honors Thesis-Unrestricted is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Honors Thesis-Unrestricted in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Honors Thesis-Unrestricted has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nihon Wa New Orleans No Ongaku Ga Daisukidesu (Japan Loves New Orleans’s Music): A Look at Japanese Interest in New Orleans Music from the 1940s to 2017 An Honors Thesis Presented to the Department of Interdisciplinary Studies of the University of New Orleans In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Interdisciplinary Studies, with University High Honors and Honors in Interdisciplinary Studies by William Archambeault May 2017 Archambeault i Acknowledgments This undergraduate Honors thesis is dedicated to Travis “Trumpet Black” Hill, a New Orleans trumpeter who died in Tokyo, Japan, on May 4, 2015, while touring Japan. -

First Steps with the Drum Set a Play Along Approach to Learning the Drums

First Steps With The Drum Set a play along approach to learning the drums JOHN SAYRE www.JohnSayreMusic.com 1 CONTENTS Page 5: Part 1, FIRST STEPS Money Beat, Four on the Floor, Four Rudiments Page 13: Part 2, 8th NOTES WITH ACCENTS Page 18: Part 3, ROCK GROOVES 8th notes, Queen, R.E.M., Stevie Wonder, Nirvana, etc. Page 22: Part 4, 16th NOTES WITH ACCENTS Page 27: Part 5, 16th NOTES ON DRUM SET Page 34: Part 6, PLAYING IN BETWEEN THE HI-HAT David Bowie, Bob Marley, James Brown, Led Zeppelin etc. Page 40: Part 7, RUDIMENTS ON THE DRUM SET Page 46: Part 8, 16th NOTE GROOVES Michael Jackson, Erykah Badu, Imagine Dragons etc. Page 57: Part 9, TRIPLETS Rudiments, Accents Page 66: Part 10, TRIPLET-BASED GROOVES Journey, Taj Mahal, Toto etc. Page 72: Part 11, UNIQUE GROOVES Grateful Dead, Phish, The Beatles etc. Page 76: Part 12, DRUMMERS TO KNOW 2 INTRODUCTION This book focuses on helping you get started playing music that has a backbeat; rock, pop, country, soul, funk, etc. If you are new to the drums I recommend working with a teacher who has a healthy amount of real world professional experience. To get the most out of this book you will need: -Drumsticks -Access to the internet -Device to play music -Good set of headphones—I like the isolation headphones made by Vic Firth -Metronome you can plug headphones into -Music stand -Basic understanding of reading rhythms—quarter, eighth, triplets, and sixteenth notes -Drum set: bass drum, snare drum, hi-hat is a great start -Other musicians to play with Look up any names, bands, and words you do not know. -

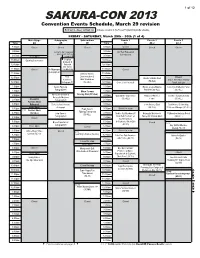

Sakura-Con 2013

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2013 Convention Events Schedule, March 29 revision FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (4 of 4) Panels 4 Panels 5 Panels 6 Panels 7 Panels 8 Workshop Karaoke Youth Console Gaming Arcade/Rock Theater 1 Theater 2 Theater 3 FUNimation Theater Anime Music Video Seattle Go Mahjong Miniatures Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Gaming Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 4C-4 401 4C-1 Time 3AB 206 309 307-308 Time Time Matsuri: 310 606-609 Band: 6B 616-617 Time 615 620 618-619 Theater: 6A Center: 305 306 613 Time 604 612 Time Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed 7:00am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (1 of 4) 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Main Stage Autographs Sakuradome Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Time 4A 4B 6E Time 6C 4C-2 4C-3 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Swasey/Mignogna showcase: 8:00am The IDOLM@STER 1-4 Moyashimon 1-4 One Piece 237-248 8:00am 8:00am TO Film Collection: Elliptical 8:30am 8:30am Closed 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am (SC-10, sub) (SC-13, sub) (SC-10, dub) 8:30am 8:30am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Orbit & Symbiotic Planet (SC-13, dub) 9:00am Located in the Contestants’ 9:00am A/V Tech Rehearsal 9:00am Open 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am AMV Showcase 9:00am 9:00am Green Room, right rear 9:30am 9:30am for Premieres -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 © Copyright by Benjamin Grant Doleac 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “We Made It Through That Water”: Rhythm, Dance, and Resistance in the New Orleans Second Line by Benjamin Grant Doleac Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Cheryl L. Keyes, Chair The black brass band parade known as the second line has been a staple of New Orleans culture for nearly 150 years. Through more than a century of social, political and demographic upheaval, the second line has persisted as an institution in the city’s black community, with its swinging march beats and emphasis on collective improvisation eventually giving rise to jazz, funk, and a multitude of other popular genres both locally and around the world. More than any other local custom, the second line served as a crucible in which the participatory, syncretic character of black music in New Orleans took shape. While the beat of the second line reverberates far beyond the city limits today, the neighborhoods that provide the parade’s sustenance face grave challenges to their existence. Ten years after Hurricane Katrina tore up the economic and cultural fabric of New Orleans, these largely poor communities are plagued on one side by underfunded schools and internecine violence, and on the other by the rising tide of post-disaster gentrification and the redlining-in- disguise of neoliberal urban policy. -

Pollution and Pandemic

WITHOUT F EAR OR FAVOUR Nepal’s largest selling English daily Vol XXVIII No. 253 | 8 pages | Rs.5 O O Printed simultaneously in Kathmandu, Biratnagar, Bharatpur and Nepalgunj 31.2 C -0.7 C Monday, November 09, 2020 | 24-07-2077 Biratnagar Jumla As winter sets in, Nepal faces double threat: Pollution and pandemic Studies around the world show the risk of Covid-19 fatality is higher with longer exposure to polluted air which engulfs the country as temperatures plummet. ARJUN POUDEL Kathmandu, relative to other cities in KATHMANDU, NOV 8 respective countries. Prolonged exposure to air pollution Last week, a 15-year-old boy from has been linked to an increased risk of Kathmandu, who was suffering from dying from Covid-19, and for the first Covid-19, was rushed to Bir Hospital, time, a study has estimated the pro- after his condition started deteriorat- portion of deaths from the coronavi- ing. The boy, who was in home isola- rus that could be attributed to the tion after being infected, was first exacerbating effects of air pollution in admitted to the intensive care unit all countries around the world. and later placed on ventilator support. The study, published in “When his condition did not Cardiovascular Research, a journal of improve even after a week on a venti- European Society of Cardiology, esti- lator, we performed an influenza test. mated that about 15 percent of deaths The test came out positive,” Dr Ashesh worldwide from Covid-19 could be Dhungana, a pulmonologist, who is attributed to long-term exposure to air also a critical care physician at Bir pollution. -

"Born in a Second Line": Glen David Andrews Shares New Orleans Musical Heritage with the World

COVER STORY "Born in a Second Line": Glen David Andrews shares New Orleans musical heritage with the world By Dean M. Shapiro Over a long, stellar career filled with honors, awards and international accolades, Glen David Andrews has just added another milestone to his list of accomplish- ments: his own namesake record label! The New Orleans born-and-raised trom- bonist and vocalist with possibly the most distinguished musical lineage in the city’s history, is touting his latest release, a digital album titled “Live in My Living Room” on the Glen David Andrews Records label (a subsidiary of Louisiana Red Hot Records). Recorded live in his French Quarter living room during the COVID-19 quarantine, the album is already making the rounds and available for downloading from Andrews’ Facebook page and website. Backed by the six-piece Glen David Andrews Band plus himself on vocals, Andrews penned five of the disc’s eight cuts. These include the lead track, “Treme Hideaway,” a tribute to a music club recently opened by his older brother, Grammy Award-winning drum- mer Derrick Tabb of the Rebirth Brass Band, in the city’s musically rich 6th Ward where the two of them grew up. As he explained in the accompanying liner notes, “This album was done to give you the experience of my live shows. Due to the current situation we couldn’t go in the studio to record this record, but nothing can stop the Spirit of the New Orleans musicians so we decided to record it live.” Despite being unable to perform in clubs, go on tour or play for special events, Andrews has not been idle. -

2008 State of New Orleans' Music Community Report

2008 State of New Orleans’ Music Community Report Copyright page Date, etc. Sweet Home New Orleans Board of Sweet Home New Orleans Staff Directors • Ali Abdin, Case Manager • Kim Foreman • Kate Benson, Program Director • Bethany Bultman • Aimee Bussells • Kat Dobson, Communications Director • Tamar Shapiro • Helene Greece, MSW, Social Worker • “Deacon” John Moore • Armand Richardson • Klara Hammer, Financial Director • Cherice Harrison-Nelson • Jordan Hirsch, Executive Director • Reid Wick • Lauren Anderson • James Morris, GSW, Director of Social Services • Scott Aiges • Lynn O’Shea, MNM, Director of Organizational • Tamara Jackson Development • Lauren Cangelosi • Joe Stern, Case Manager • David Freedman • Paige Royer (please alphabetize board list) (possible heading or title here) This report represents the culmination of three years of our direct service to New Orleans’ music community. Renew Our Music, founded as New Orleans Musicians Hurricane Relief Fund, began issuing relief checks to New Orleans artists while floodwaters still covered parts of the city. Sweet Home New Orleans evolved in 2006 to provide case management and housing assistance to the musicians, Mardi Gras Indians, and Social Aid & Pleasure Club members struggling to return to their neighborhoods. In 2008, these agencies merged to form a holistic service center for the music community, assisting with everything from home renovations to instrument repair. As of the third anniversary of the storm, we have distributed $2,000,000 directly to more than 2,000 of New Orleans’ cultural tradition bearers. Our case workers assess clients’ individual needs to determine how our resources, and those of our partnering agencies, can most effectively assist them in perpetuating our city’s unique music culture. -

Dirty Dozen Brass Band from Purists to Those Who Prefer Fourth Offering in the Formation Call 463-9670

Page 6. The VMI Cadet. February s. 1967 At Ease Sound Off Curran Bowen by: Scott McCumber The Housemartins—"London Mid-Winter 0 Hull 4" Once gain, the subject of this week's column is an English band, and once again, the music Weekend is good. Sorry to disappoint all the American music lovers, but Mid winters already 1 Can you together a great show not to be the sad fact is that a rather believe it? There is no need wor- missed. large majority of the new music rying about what's happening. Also Saturday is the continua- is from England. It is time to take a break from tion of the W&L Superdance. Another new band, "The the books and recouperate this This fund raiser for Muscular Housemartin's "London O Hull weekend. Distrophy Association features 4" is an exceptional piece of Friday night is the formal hop SG & L and the White Animals. work. (By the way, anyone who right here at VMI in Cocke Hall. Cost is about $10. Look for a knows the meaning behind the The gals will be dolled up and possible permit. (Thanks Kevin album's title feel free to let me ready to party with the Mighty Alvis.) know). The music on the album Majors. Don't let them down And to cap off this weekend, is fast paced and exciting. Most fellas. as if it's not enough, ZoUman's of the songs contain a "guitar If Post is cramping your style Pavillion opens Sunday from 1 Billy Idol *'Whiplash Smile' solo of some repute," and there and you are on the road, then to 5 p.m.