Interview with Terrell (Terry) E. Arnold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music in the Heart of Manila: Quiapo from the Colonial Period to Contemporary Times: Tradition, Change, Continuity Ma

Music in The Heart of Manila: Quiapo from the Colonial Period to Contemporary Times: Tradition, Change, Continuity Ma. Patricia Brillantes-Silvestre A brief history of Quiapo Quiapo is a key district of Manila, having as its boundaries the winding Pasig River and the districts of Sta. Cruz, San Miguel and Sampaloc. Its name comes from a floating water lily specie called kiyapo (Pistia stratiotes), with thick, light-green leaves, similar to a tiny, open cabbage. Pre-1800 maps of Manila show Quiapo as originally a cluster of islands with swampy lands and shallow waters (Andrade 2006, 40 in Zialcita), the perfect breeding place for the plant that gave its name to the district. Quiapo’s recorded history began in 1578 with the arrival of the Franciscans who established their main missionary headquarters in nearby Sta. Ana (Andrade 42), taking Quiapo, then a poor fishing village, into its sheepfold. They founded Quiapo Church and declared its parish as that of St. John the Baptist. The Jesuits arrived in 1581, and the discalced Augustinians in 1622 founded a chapel in honor of San Sebastian, at the site where the present Gothic-style basilica now stands. At about this time there were around 30,000 Chinese living in Manila and its surrounding areas, but the number swiftly increased due to the galleon trade, which brought in Mexican currency in exchange for Chinese silk and other products (Wickberg 1965). The Chinese, noted for their business acumen, had begun to settle in the district when Manila’s business center shifted there in the early 1900s (originally from the Parian/Chinese ghetto beside Intramuros in the 1500s, to Binondo in the 1850s, to Sta.Cruz at the turn of the century). -

Producing Rizal: Negotiating Modernity Among the Filipino Diaspora in Hawaii

PRODUCING RIZAL: NEGOTIATING MODERNITY AMONG THE FILIPINO DIASPORA IN HAWAII A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ASIAN STUDIES AUGUST 2014 By Ai En Isabel Chew Thesis Committee: Patricio Abinales, Chairperson Cathryn Clayton Vina Lanzona Keywords: Filipino Diaspora, Hawaii, Jose Rizal, Modernity, Rizalista Sects, Knights of Rizal 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………..…5 Chapter 1 Introduction: Rizal as a Site of Contestation………………………………………………………………………………………....6 Methodology ..................................................................................................................18 Rizal in the Filipino Academic Discourse......................................................................21 Chapter 2 Producing Rizal: Interactions on the Trans-Pacific Stage during the American Colonial Era,1898-1943…………………………..………………………………………………………...29 Rizal and the Philippine Revolution...............................................................................33 ‘Official’ Productions of Rizal under American Colonial Rule .....................................39 Rizal the Educated Cosmopolitan ..................................................................................47 Rizal as the Brown Messiah ...........................................................................................56 Conclusion ......................................................................................................................66 -

Countdown to Martial Law: the U.S-Philippine Relationship, 1969

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Graduate Masters Theses Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses 8-31-2016 Countdown to Martial Law: The .SU -Philippine Relationship, 1969-1972 Joven G. Maranan University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umb.edu/masters_theses Part of the Asian History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Maranan, Joven G., "Countdown to Martial Law: The .SU -Philippine Relationship, 1969-1972" (2016). Graduate Masters Theses. 401. https://scholarworks.umb.edu/masters_theses/401 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Doctoral Dissertations and Masters Theses at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COUNTDOWN TO MARTIAL LAW: THE U.S.-PHILIPPINE RELATIONSHIP, 1969-1972 A Thesis Presented by JOVEN G. MARANAN Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2016 History Program © 2016 by Joven G. Maranan All rights reserved COUNTDOWN TO MARTIAL LAW: THE U.S.-PHILIPPINE RELATIONSHIP 1969-1972 A Thesis Presented by JOVEN G. MARANAN Approved as to style and content by: ________________________________________________ Vincent Cannato, Associate Professor Chairperson of Committee ________________________________________________ David Hunt, Professor Member ________________________________________________ Christopher Capozzola, Associate Professor MIT Member _________________________________________ Vincent Cannato, Program Director History Graduate Program _________________________________________ Tim Hascsi, Chairperson History Department ABSTRACT COUNTDOWN TO MARTIAL LAW: THE U.S.-PHILIPPINE RELATIONSHIP, 1969-1972 August 2016 Joven G. -

Download RIPH

UNIT 4: Social, Political, Economic and Cultural Issues in Philippine History IV. Topic: Social, political, economic and cultural issues in Philippine history: Mandated topics: 1. Land and Agrarian Reform Policies 2. The Philippine Constitutions of 1899, 1935, 1973 and 1987 3. Taxation Additional topics: Filipino Cultural heritage; Filipino-American relations; Government peace treaties with the Muslim Filipinos; Institutional history of schools, corporations, industries, religious groups and the like; Biography of a prominent Filipino Learning Outcomes: Effectively communicate, using various techniques and genres, their historical analysis of a particular event or issue that could help other people understand the chosen topic; Propose recommendations or solutions to present day problems based on their own understanding of their root causes, and their anticipation of future scenarios; Display the ability to work in a multi-disciplinary team and can contribute to a group endeavor; Methodology: Lecture/Discussion; Library and Archival research; Document analysis Group reporting; Documentary Film Showing Readings: 4.1. Land and Agrarian Reform: Primary Sources: a. the American period and Quezon administration : "The Philippine Rice Share Tenancy Act of 1933 (Act 4054) http://www.chanrobles.com/acts/actsno4054.html b. the Magsaysay administration: "Agricultural Tenancy Act of the Philippines of 1954 (R.A. 1199) http://www.lawphil.net/statutes/repacts/ra1954/ra_1199_1954.html c. the Macapagal administration : Agricultural Land Reform Code of 1963 (R.A 3844) http://www.lawphil.net/statutes/repacts/ra1963/ra_3844_1963.html d. the Marcos regime and under Martial Law P.D. 27 of 1972 http://www.lawphil.net/statutes/presdecs/pd1972/pd_27_1972.html e. the Cory Aquino administration Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program of 1988 (R.A. -

Beyond Boxers Or Briefs Educate Early, Vote Often by Joshua Levy an Interview with Civicyouth.Org’S Peter Levine Letters to the Editor

CHAPTER NEWS MEMBER NEWS AND MORE TVNNFS 2008 :PVOH7PUFST "DUJWJTUTBSF3FBEZUPCF)FBSE .JTTJPOUP.BOHV[J QH $BMMFEUP"GSJDB 8F'PVOE0VSTFMWFT CZ#SJDF/JFMTFO 04 .FNPJSTPGB4USFFU.BSDIFS QH 12 .Z"DUJWJTNJO3FUSPTQFDU CZ+PTF%BMJTBZ+S #FZPOE#PYFSTPS#SJFGT "DUJWJTU 5FDI8BUDIFS+PTIVB-FWZ QH 14 5BDLMFT/FX.FEJBBOE1PMJUJDT &EVDBUF&BSMZ 7PUF0GUFO $SVODIJOHUIF/VNCFST QH 18 XJUI$*3$-&µT1FUFS-FWJOF The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the staff of Phi Kappa Phi Forum or the Board of Directors of The Honor Society of Phi Kappa Phi. phi kappa phi forum (issn 1538-5914) is published quarterly by The Honor Society of Phi Kappa Phi, 7576 Goodwood Blvd., Baton Rouge, la 70806. Printed at R.R. Donnelley, 1160 N. Main, Pontiac, il 61764. the honor society of phi kappa phi was founded in ©The Honor Society of Phi 1897 and became a national organization through the Kappa Phi, 008. All rights efforts of the presidents of three state universities. Its reserved. Non-member primary objective has from the first been the recognition subscriptions $30 per and encouragement of superior scholarship in all fields of year. Single copies $10 study. Good character is an essential supporting attribute each. Periodicals postage for those elected to membership. The motto of the Society paid Baton Rouge, la and additional mailing is phiosophia krateito phótón, which is freely translated as offices. Material intended “Let the love of learning rule humanity.” for publication should be Phi Kappa Phi encourages and recognizes academic addressed to Traci Navarre, excellence through several programs. Through its The Honor Society of Phi Kappa Phi, 7576 Goodwood awards and grants programs, the Society each triennium Blvd., Baton Rouge, la 70806. -

Arnold, Terrell E

Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project TERRELL (TERRY) E. ARNOLD Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview dates: March 9, 2000 Copyright 2003 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born and raised in West Virginia U.S. Navy, World War II, Korean War China Columbia University (Champlain) (SUNY); San Jose State College, Stanford University Teacher, Oakland, California - 1954-1956 Entered Foreign Service - 1959 State Department - INR - Latin American Affairs 1958-1959 Mexico Cairo, Egypt - Economic Officer 1959-1961 Nasser Environment Petroleum Israel Suez Contacts Aswan Dam UAR splits Calcutta, India - Economic Officer 1962-1964 Economy AID Environment Mother Theresa Tea U.S. military aid University of California - Economic Training 1964-1965 Theory versus practice Free Speech Movement Terrorist groups State Department - Economic Bureau - Food Policy 1965-1969 Africa Disease Competition Colombo, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) - DCM 1969-1970 Politics Tamils Madam Bandaranaike election National War College 1970-1971 Vietnam Manila, Philippines - Economic/Commercial Counselor 1971-1976 U.S. presence/interests Laurel-Langley Agreement Marcoses Vietnam refugees State Department - Senior Inspector 1976-1978 Post inspections Sao Paulo, Brazil - Consul General 1978-1980 U.S. interests Environment Economy Relations Human rights USIS National War College - Faculty Member 1980-1983 Courses of study Counterterrorism State Department support State Department - Counterterrorism - Deputy Assistant Secretary 1983-1985 Near East terrorism FBI State-sponsored terrorism Israel State Department - Counterterrorism - Consultant 1985-1986 State-sponsored terrorism Fighting Back Intelligence community Iran-Contra State Department - Emergency Management Training 1986 INTERVIEW Q: This is an interview with Terrell E. Arnold. This is being done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, and I'm Charles Stuart Kennedy. -

The Entertainment Capital of Southeast Asia Manila

Manila The Entertainment Capital The Philippines is a country of 7,107 vibrant and colourful islands, all pulsating with life and teeming of Southeast Asia with flavour. Yet, it is in Manila where you can LAOAG hear its heart beating the loudest! Manila is a Banaue sophisticated capital - the seat of power, centre Getting there Manila Luzon of trade and industry, commerce, education, Major Airport Gateways: PHILIPPINE SEA entertainment and the arts. It is an invigorating Ninoy Aquino International Airport (NAIA) Airport Code MNL blend of some of the country’s oldest and MANILAMANILA richest heritage treasures, and the most modern Air Transport: Aside from being a major international gateway city, metropolitan features of the Philippine landscape. Mindoro Its people have acquired an urban cosmopolitan Manila is also a jump off point for intra-regional air travel. The Ninoy Aquino International Airport services over Boracay air about them, but have managed to retain their Aklan Samar 40 airlines providing daily services to more than 26 cities warm and friendly smiles that have made Filipino Visayas and 19 countries worldwide. Duty-free centres, tourist Palawan Panay Iloilo Cebu hospitality renowned throughout the world. Leyte information counters, hotel and travel agency CEBUCEBU representatives, banks, postal services, a medical clinic, and Manila started as a small tribal settlement along the a baggage deposit area support airport operations. NAIA is Negros Bohol Pasig River before it became the seat of Spanish also a series of domestic airport terminals that act as hubs SULU SEA colonial rule in Asia during the 16th century. to various regional and provincial airports in the country. -

ANG Expand and Strengthen the Protest Movement Against Aquino's

Pahayagan ng Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas ANG Pinapatnubayan ng Marxismo-Leninismo-Maoismo English Edition Vol. XLIV No. 17 September 7, 2013 www.philippinerevolution.net Editorial Expand and strengthen the protest movement against Aquino's corruption he huge August 26 demonstration at the Luneta Park in Manila the broad masses of the people. and various other places here and abroad was an indicator of It now faces the widespread Tthe Filipino people's widespread anger at the pork barrel sys- hatred of the middle strata of tem. Through this protest, the people demonstrated their wrath at professionals, teachers and oth- the bureaucratic plunder of public funds and their use by the ruling er employees, doctors, nurses Aquino regime to dominate reactionary politics. and health workers, church peo- ple and lawyers. All of them The pork barrel issue has their apathy at the glaring gap were at the receiving end of further laid bare the ruling between their affluence and the Aquino's attempts to entice classes' greed and underscored hard, deprived and wretched them with propaganda on re- their deliberate refusal to heed lives of the toiling masses. form and good governance. the people's grievances and Only at the middle of its six- The huge protest action and year term, continually expanding move- the Aquino ment against the pork barrel regime is now comprise an important leap in severely iso- the widespread participation of lated from ordinary folk in political action. The people's burgeoning an- ger is rooted in the deepening and expanding socio-economic In this issue... Protests greet key US officials 5 Raid and ambush in ComVal and Agusan Sur 8 Antimining datu in Davao del Sur killed 11 crisis. -

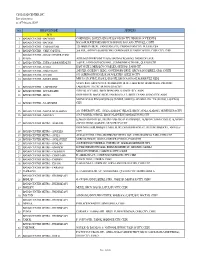

CIS BAYAD CENTER, INC. List of Partners As of February 2020*

CIS BAYAD CENTER, INC. List of partners as of February 2020* NO. BRANCH NAME ADDRESS BCO 1 BAYAD CENTER - BACOLOD COKIN BLDG. LOPEZ JAENA ST.,BACOLOD CITY, NEGROS OCCIDENTAL 2 BAYAD CENTER - BACOOR BACOOR BOULEVARD, BRGY. BAYANAN, BACOOR CITY HALL, CAVITE 3 BAYAD CENTER - CABANATUAN 720 MARILYN BLDG., SANGITAN ESTE, CABANATUAN CITY, NUEVA ECIJA 4 BAYAD CENTER - CEBU CAPITOL 2nd FLR., AVON PLAZA BUILDING, OSMENA BOULEVARD CAPITOL. CEBU CITY, CEBU BAYAD CENTER - DAVAO CENTER POINT 5 PLAZA ATRIUM CENTERPOINT PLAZA, MATINA CROSSING, DAVAO DEL SUR 6 BAYAD CENTER - EVER COMMONWEALTH 2ndFLR., EVER GOTESCO MALL, COMMONWEALTH AVE., QUEZON CITY 7 BAYAD CENTER - GATE2 EAST GATE 2, MERALCO COMPLEX, ORTIGAS, PASIG CITY 8 BAYAD CENTER - GMA CAVITE 2ND FLR. GGHHNC 1 BLDG., GOVERNORS DRVE, BRGY SAN GABRIEL, GMA, CAVITE 9 BAYAD CENTER - GULOD 873 QUIRINO HWAY,GULOD,NOVALICHES, QUEZON CITY 10 BAYAD CENTER - KASIGLAHAN MWCI.SAT.OFFICE, KASIGLAHAN VIL.,BRGY.SAN JOSE,RODRIGUEZ, RIZAL SPACE R-O5 GROUND FLR. REMBRANDT BLDG. LAKEFRONT BOARDWALK, PRESIDIO 11 BAYAD CENTER - LAKEFRONT LAKEFRONT, SUCAT, MUNTINLUPA CITY 12 BAYAD CENTER - LCC LEGAZPI 4TH FLR. LCC MALL, BRGY.DINAGAAN, LEGASPI CITY, ALBAY 13 BAYAD CENTER - LIGAO GROUND FLR. MA-VIC BLDG, SAN ROQUE ST., BRGY. DUNAO, LIGAO CITY, ALBAY MAYNILAD LAS PIÑAS BUSINESS CENTER, MARCOS ALVAREZ AVE. TALON UNO, LAS PIÑAS 14 BAYAD CENTER - M. ALVAREZ CITY 15 BAYAD CENTER - MAYNILAD ALABANG 201 UNIVERSITY AVE., AYALA ALABANG VILLAGE, BRGY. AYALA ALABANG, MUNTINLUPA CITY 16 BAYAD CENTER - MAYSILO 479-F MAYSILO CIRCLE, BRGY. PLAINVIEW, MANDALUYONG CITY LOWER GROUND FLR., METRO GAISANO SUPERMARKET, ALABANG TOWN CENTER, ALABANG- 17 BAYAD CENTER METRO - ALABANG ZAPOTE ROAD, ALABANG, MUNTINLUPA CITY GROUND FLOOR,MARQUEE MALL BLDG, DON BONIFACIO ST., PULUNG MARAGUL, ANGELES 18 BAYAD CENTER METRO - ANGELES CITY 19 BAYAD CENTER METRO - AYALA AYALA CENTER, CEBU ARCHBISHOP REYES AVE., CEBU BUSINESS PARK, CEBU CITY 20 BAYAD CENTER METRO - AYALA FELIZ MARCOS HI-WAY, LIGAYA, CORNER JP RIZAL, PASIG CITY 21 BAYAD CENTER METRO - BANILAD A.S FORTUNA CORNER H. -

Divine Mercy in the Philippines

Divine Mercy in the Philippines A collective work by Ann T. Burgos, Edita T. Burgos, Manman L. Dejeto, Lourdes M. Fernandez, Renato L. Fider, Alma A. Ocampo, Joel C. Paredes, Teofilo P. Pescones , Filemon L. Salcedo and Monina S. Tayamen The Editorial Board Edita T. Burgos, Lourdes M. Fernandez, Renato L. Fider, Alma A. Ocampo, Joel C. Paredes, Teofilo P. Pescones, Filemon L. Salcedo and Monina S. Tayamen Book Editors Lourdes M. Fernandez and Joel C. Paredes Writers Paul C. Atienza, Ann T. Burgos, Manuel Cayon, Ian Go, Wilfredo Rodolfo III and Ramona M. Villarica Cover Design Leonilo Doloricon Photographers Rhoy Cobilla, Manman L. Dejeto, Roy Domingo, Gabriel Visaya Sr. and Sammy Yncierto Layout Benjamin G. Laygo, Jr. Editorial and Production Coordination Ressie Q. Benoza Finance Dioscora C. Amante, Virginia S. Barbers, Elizabeth T. Delarmente, Nora S. Santos and Linda C. Villamor Editorial Concept and Design by People and Advocacy Published by the Divine Mercy Apostolate of the Philippines Makati, Philippines April 2008 2 Divine Mercy in the Philippines In Memory of St. Maria Faustina Kowalska and Pope John Paul II, the messengers of global peace. This book is also a tribute to all those who have opened their lives to accept the devotion to the DIVINE MERCY, especially the members of the clergy, the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church and the lay people. In the Philippines, we dedicate this collective work to the untiring effort of Monsignor Josefino S. Ramirez, the first Filipino priest who relentlessly embraced our devotion. Divine Mercy in the Philippines 3 Table of contents Benefactors, Sponsors and Patrons 6 The Mercy Centers 40 Foreword 7 The first Divine Mercy Shrine 44 A devotion unfolds 8 Divine Mercy Apostolate- Archdiocese of Manila 48 A Bishop’s constant message: Mercy is all we need 32 Divine Mercy Movement in the Philippines and the Marians of the Immaculate Conception 50 St. -

Download the Case Study Report on Prevention in the Philippines Here

International Center for Transitional Justice Disrupting Cycles of Discontent TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE AND PREVENTION IN THE PHILIPPINES June 2021 Cover Image: Relatives and friends hold balloons during the funeral of three-year-old Kateleen Myca Ulpina on July 9, 2019, in Rodriguez, Rizal province, Philippines. Ul- pina was shot dead by police officers conducting a drug raid targeting her father. (Ezra Acayan/Getty Images) Disrupting Cycles of Discontent TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE AND PREVENTION IN THE PHILIPPINES Robert Francis B. Garcia JUNE 2021 International Center Disrupting Cycles of Discontent for Transitional Justice About the Research Project This publication is part of an ICTJ comparative research project examining the contributions of tran- sitional justice to prevention. The project includes country case studies on Colombia, Morocco, Peru, the Philippines, and Sierra Leone, as well as a summary report. All six publications are available on ICTJ’s website. About the Author Robert Francis B. Garcia is the founding chairperson of the human rights organization Peace Advocates for Truth, Healing, and Justice (PATH). He currently serves as a transitional justice consultant for the Philippines’ Commission on Human Rights (CHR) and manages Weaving Women’s Narratives, a research and memorialization project based at the Ateneo de Manila University. Bobby is author of the award-winning memoir To Suffer thy Comrades: How the Revolution Decimated its Own, which chronicles his experiences as a torture survivor. Acknowledgments It would be impossible to enumerate everyone who has directly or indirectly contributed to this study. Many are bound to be overlooked. That said, the author would like to mention a few names represent- ing various groups whose input has been invaluable to the completion of this work. -

Duterte Mediated Populism Mccargo .Pdf

This is a repository copy of Duterte's Mediated Populism. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/123686/ Version: Accepted Version Article: McCargo, D orcid.org/0000-0002-4352-5734 (2016) Duterte's Mediated Populism. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 38 (2). pp. 185-190. ISSN 0129-797X https://doi.org/10.1355/cs38-2a This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Contemporary Southeast Asia. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Duterte’s Mediated Populism DUNCAN McCARGO DUNCAN McCARGO is Professor of Political Science at the University of Leeds and a Visitor at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton. Postal address: School of Politics and International Studies, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK; email: [email protected] Rodrigo Duterte’s final miting de avance election rally in the capital’s Luneta Park was a spectacular event, just two nights before the 9 May polls.