Interview #72

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Headquarters, Department of the Army

Headquarters, Department of the Army Department of the Army Pamphlet 27-50-396 May 2006 Articles Nation-Building in Afghanistan: Lessons Identified in Military Justice Reform Major Sean M. Watts & Captain Christopher E. Martin The Solomon Amendment: A War on Campus Major Anita J. Fitch TJAGLCS Practice Note The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School New Resources for Servicemembers Civil Relief Act (SCRA) and Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act (USERRA) Practitioners Center for Law and Military Operations (CLAMO) Practice Notes The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School Update on Department of State and Department of Defense Coordination of Reconstruction and Stabilization Assistance Joint Multinational Readiness Center Transformation: An Adaptive Expeditionary Mindset Book Review Announcements CLE News Current Materials of Interest Editor, Major Anita J. Fitch Assistant Editor, Captain Colette E. Kitchel Technical Editor, Charles J. Strong The Army Lawyer (ISSN 0364-1287, USPS 490-330) is published monthly submitted via electronic mail to [email protected] or on 3 1/2” by The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School, Charlottesville, diskettes to: Editor, The Army Lawyer, The Judge Advocate General’s Virginia, for the official use of Army lawyers in the performance of their Legal Center and School, U.S. Army, 600 Massie Road, ATTN: ALCS- legal responsibilities. Individual paid subscriptions to The Army Lawyer are ADA-P, Charlottesville, Virginia 22903-1781. Articles should follow The available for $45.00 each ($63.00 foreign) per year, periodical postage paid at Bluebook, A Uniform System of Citation (18th ed. 2005) and Military Charlottesville, Virginia, and additional mailing offices (see subscription form Citation (TJAGLCS, 10th ed. -

PDF Download Yeah Baby!

YEAH BABY! PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jillian Michaels | 304 pages | 28 Nov 2016 | Rodale Press Inc. | 9781623368036 | English | Emmaus, United States Yeah Baby! PDF Book Writers: Donald P. He was great through out this season. Delivers the right impression from the moment the guest arrives. One of these was Austin's speech to Dr. All Episodes Back to School Picks. The trilogy has gentle humor, slapstick, and so many inside jokes it's hard to keep track. Don't want to miss out? You should always supervise your child in the highchair and do not leave them unattended. Like all our highchair accessories, it was designed with functionality and aesthetics in mind. Bamboo Adjustable Highchair Footrest Our adjustable highchair footrests provide an option for people who love the inexpensive and minimal IKEA highchair but also want to give their babies the foot support they need. FDA-grade silicone placemat fits perfectly inside the tray and makes clean-up a breeze. Edit page. Scott Gemmill. Visit our What to Watch page. Evil delivers about his father, the entire speech is downright funny. Perfect for estheticians and therapists - as the accent piping, flattering for all design and adjustable back belt deliver a five star look that will make the staff feel and However, footrests inherently make it easier for your child to push themselves up out of their seat. Looking for something to watch? Plot Keywords. Yeah Baby! Writer Subscribe to Wethrift's email alerts for Yeah Baby Goods and we will send you an email notification every time we discover a new discount code. -

Commissioned Officer and Warrant Officer Career Management Program

Kansas Army National Guard Standard Operating Procedure 600-100-1 Personnel – Officer and Warrant Officer Commissioned Officer and Warrant Officer Career Management Program Adjutant General’s Department Headquarters, Kansas Army National Guard Topeka, Kansas 15 April 2021 UNCLASSIFIED SUMMARY OF CHANGE KSARNG 600-100-1 SOP 2021 Officer and Warrant Officer Career Management Program This revision, dated 15 April 2021 o Updates References to Publications and Forms (Throughout) o Added Enterprise Marketing & Behavioral Economics FA (58) to Operations Support Division (CH 2- 1.b.(1)) o Removed Electronic Warfare FA (29) from Information Dominance Division (FA 29 was rescinded effective October 2018) (CH 2-1.d) o Added SSC MSO information (CH 2-2.b.5) o Clarifies requirement for Commander KSARNG Medical Detachment, KSARNG Senior TJAG, and KSARNG Senior Chaplain to brief specialty branch officer assignments in conjunction with the LDAP (CH 2-3.c) o Specifies requirement to submit Officer Personnel Action Requests using the IPPS-A Customer Relations Management Ticket System with IPPS-A (CH 2-4) o Clarifies the authority of The Adjutant General and the LDAP to re-branch an officer without their consent (CH 3-2) o Adds responsibility for OPM to prepare annual accession and branching mission (CH 3-3.k.2a-b) o Adds details and branch detailing to branch assignment process (CH 3-3.1.2.b-c) o Modifies battalion command assignment consideration timeline (CH 3-6.i.(1)(a)(ii)) o Changes timeline for officer assignment projections by MSCs (CH 3-6.j) o -

Scs-Swim-Guide.Pdf (Socalswim.Org

SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA SWIMMING, INC. (CA) CA is a Local Swimming Committee of USA SWIMMING, INC 2021 Swim Guide Published by the House of Delegates of Southern California Swimming Terry Stoddard, General Chairman SWIM OFFICE 28000 S. Western Ave., #226 San Pedro, CA 90732 -or- Postal Annex – Rancho Palos Verdes Attn: Southern California Swimming 28625 S. Western Ave., Box #182 Rancho Palos Verdes, CA 90275 (310) 684-1151 Monday - Friday, 8:30 a.m. - 4 p.m. Visit Southern California Swimming (CA) on the internet at https://www.socalswim.org Email: [email protected] NOTE: Updates to the 2021 Swim Guide will be available during the calendar year online at socalswim.org 1 Greetings, and Welcome to Southern California Swimming (CA)! CA is one of 59 Local Swimming Committees (LSCs) within USA Swimming. USA Swimming is one of the National Governing Bodies (NGBs) under the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) and the USOC is part of the Federation Internationale de Natation (FINA). FINA is the swimming organization within the International Olympic Committee (IOC)….the group that organizes the Olympics. So, your club is the grassroots level of membership for swimming that goes all the way up to the Olympics! From San Luis Obispo down to San Clemente and over to Las Vegas, we have about 25,000 athletes, coaches, officials and parent volunteers in our membership. Because our LSC is so large--the largest membership in the country--we have 6 Geographic sub- Committees: Coastal, Desert, Eastern, Metro, Pacific and Orange to help with administration and local competitions. CA oversees registration for all our clubs and individual members, swim meet sanctions—roughly 400 swim meets per year are sanctioned/approved by CA, multiple camps and all-star teams, as well as educational programs for everyone. -

Al-Hadl Yahya B. Ai-Husayn: an Introduction, Newly Edited Text and Translation with Detailed Annotation

Durham E-Theses Ghayat al-amani and the life and times of al-Hadi Yahya b. al-Husayn: an introduction, newly edited text and translation with detailed annotation Eagle, A.B.D.R. How to cite: Eagle, A.B.D.R. (1990) Ghayat al-amani and the life and times of al-Hadi Yahya b. al-Husayn: an introduction, newly edited text and translation with detailed annotation, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/6185/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ABSTRACT Eagle, A.B.D.R. M.Litt., University of Durham. 1990. " Ghayat al-amahr and the life and times of al-Hadf Yahya b. al-Husayn: an introduction, newly edited text and translation with detailed annotation. " The thesis is anchored upon a text extracted from an important 11th / 17th century Yemeni historical work. -

Season Ticket Guide 2020-2021 Season

SEASON TICKET GUIDE 2020-2021 SEASON KEEP CALM AND JAZZ ON JAZZARTSGROUP.ORG JAG.TV Don’t miss a single exciting moment of the 2020-2021 season, and now enjoy it all from the comfort and safety of home Go to www.JAG.tv to purchase your season packages and single tickets. JAZZ at the SOUTHERN THEATRE PACKAGE $90 • Package of all four (4) on-demand concerts: $90 (sold at www.JAG.tv) • Individual on-demand concerts: $25 (sold at www.JAG.tv) • Limited in-theatre individual socially-distanced seating: $70 (sold one-week in advance of the concert at www.CBUSArts.com. Full package purchasers will receive a $25 discount on in-theatre ticket purchases.) JAZZ at the LINCOLN THEATRE PACKAGE $50 • Package of all four (4) live-streamed and on-demand concerts: $50 (sold at www.JAG.tv) • Individual live-streamed and on-demand concerts: $15 (sold at www.JAG.tv) • Limited in-theatre individual socially-distance searing: $30 (go on-sale one-week in advance of concert, sold at www.CBUSArts.com) I WANT IT ALL! PACKAGE $200 Includes ALL on-demand JAZZ at the SOUTHERN THEATRE concerts + ALL live-streamed and on-demand JAZZ at the LINCOLN THEATRE concerts + ALL PBJ & Jazz online concerts + ALL Offstage Live online interviews and artist Q&As throughout the season: $200. The I WANT IT ALL! package also includes advance purchase and discount opportunities for the in-theatre JAZZ at the SOUTHERN THEATRE experience. Full and prorated packages are available for purchase at www.JAG.tv Prices shown do not include CAPA facility fee or City of Columbus Arts & Culture fee for in-theatre tickets, or processing fee for online/on-demand purchases. -

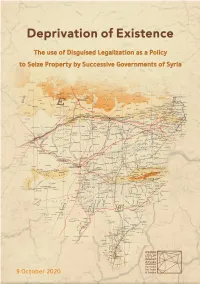

In PDF Format, Please Click Here

Deprivatio of Existence The use of Disguised Legalization as a Policy to Seize Property by Successive Governments of Syria A special report sheds light on discrimination projects aiming at radical demographic changes in areas historically populated by Kurds Acknowledgment and Gratitude The present report is the result of a joint cooperation that extended from 2018’s second half until August 2020, and it could not have been produced without the invaluable assistance of witnesses and victims who had the courage to provide us with official doc- uments proving ownership of their seized property. This report is to be added to researches, books, articles and efforts made to address the subject therein over the past decades, by Syrian/Kurdish human rights organizations, Deprivatio of Existence individuals, male and female researchers and parties of the Kurdish movement in Syria. Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) would like to thank all researchers who contributed to documenting and recording testimonies together with the editors who worked hard to produce this first edition, which is open for amendments and updates if new credible information is made available. To give feedback or send corrections or any additional documents supporting any part of this report, please contact us on [email protected] About Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) STJ started as a humble project to tell the stories of Syrians experiencing enforced disap- pearances and torture, it grew into an established organization committed to unveiling human rights violations of all sorts committed by all parties to the conflict. Convinced that the diversity that has historically defined Syria is a wealth, our team of researchers and volunteers works with dedication at uncovering human rights violations committed in Syria, regardless of their perpetrator and victims, in order to promote inclusiveness and ensure that all Syrians are represented, and their rights fulfilled. -

Turning FOB Blackhawk Over to Iraq

in the Vol. II, Issue 4 ZONE September 2009 1 in the ZONE September 2009 —Table of Contents— 3 From the Top in the 5 Farewell Baghdad E.R. Troops render a final salute to Ibn Sina Hospital ZONE 6 Opening new doors NATO mission has new home 7 Monday Morning Football Wisconsin troops cheer for the Packers 8 Baghdad Yacht Club Soldiers take remote controlled boats for a spin 10 A learning opportunity An Iraqi General shares personal insights with JASG troops 11 A doctor treating different breeds Vet clinic keeps working dogs mission-ready 13 The changing face of the IZ Produced by the Joint Area Turning FOB Blackhawk over to Iraq Support Group-Central Public 14 Chaplain’s word Affairs Office New strength 15 JAG brief Family support JASG-C Commander: 16 Outside the zone: Camp Bucca Col. Steven Bensend 18 Know where to go: Life on the FOBs JASG-C CSM: Command Sgt. Maj. Edgar Hansen 19 Around the zone 20 End zone The last page JASG-C Public Affairs Officer: Lt. Col. Tim Donovan In The Zone editor: Sgt. Michelle Gonzalez JASG-C Public Affairs Staff: Capt. Joy LeMay Sgt. Frank Merola Spc. Tyler Lasure In The Zone is published monthly as an electronic news magazine under provisions of AR 360-1, para 3-6 by the Command Director- Sgt. Carl Seim retrieves his boat from one of Prosperity’s lakes ate’s (JASG-C) Command for all after competing against two other members of Prosperity’s military personnel serving in the Baghdad Yacht Club. -

Nickelodeon Greenlights Daddy's Home, the First-Ever Original Comedy Pilot for Nick at Nite, Starring Scott Baio As a Stay-At-Home Dad

Nickelodeon Greenlights Daddy's Home, the First-Ever Original Comedy Pilot for Nick at Nite, Starring Scott Baio as a Stay-at-Home Dad Multi-Camera Pilot Created by Tina Albanese and Patrick Labyorteaux; Executive Produced by Eric Bischoff, Jason Hervey, Albanese, Labyorteaux and Baio SANTA MONICA, Calif., Oct. 24, 2011 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ -- Nickelodeon has ordered its first-ever original scripted comedy pilot, Daddy's Home, starring Scott Baio, it was announced today by Marjorie Cohn, President, Original Programming and Development, Nickelodeon. A multi-camera, half-hour comedy for Nick at Nite, Daddy's Home follows David Hobbs (Baio) an actor who, after ten years of starring as America's favorite TV dad, becomes a stay-at-home father to honor the deal he made with his soap star wife so that she may return to the limelight. The project comes from creators/executive producers Tina Albanese and Patrick Labyorteaux and is helmed by executive producers Eric Bischoff and Jason Hervey through their production company Bischoff Hervey Entertainment (BHE), along with Baio. Daddy's Home marks Hervey and Baio's return to scripted comedy, with BHE having previously collaborated on three acclaimed unscripted series including Scott Baio is 45 and Single, Scott Baio is 46 and Pregnant, and Confessions of a Teen Idol. "Scott Baio is an actor known and beloved by today's Nick at Nite viewers, many of whom are parents," said Cohn. "His new project will put a contemporary and comedic twist on parenthood that will make for a great addition to our existing slate of family programming." "It's nice to be back home in an arena where I'm completely comfortable and with a show idea that I love," added Baio. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

Comprehensive Review of the DON Uniformed Legal Communities

(PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK) Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Background ........................................................................................................ 2 1.3 Core Themes — The Panel “Lens” .................................................................... 4 1.4 Report Structure ................................................................................................. 8 1.5 Findings & Recommendations ........................................................................... 8 1.6 Implementation Oversight ................................................................................ 11 1.7 Submission of Report ....................................................................................... 12 2. REVIEW SCOPE AND METHODOLOGY .............................................................. 13 2.1 SECNAV Direction ........................................................................................... 13 2.2 Previous Reviews ............................................................................................. 14 2.3 Information Gathering ...................................................................................... 16 2.3.1 Navy Working Group Summary ................................................................. 16 2.3.2 Marine Corps Working Group Summary -

'GOOD WITCH' Cast Bios CATHERINE BELL

‘GOOD WITCH’ Cast Bios CATHERINE BELL (Cassie Nightingale) – Catherine Bell is best known for her work as the headstrong Marine Corps attorney Lt. Sarah ‘Mac’ MacKenzie on the action drama series “JAG” and in the ensemble drama series “Army Wives,” as Denise Sherwood, a devoted wife who has returned to work as a nurse while her husband is a major in Iraq and whose son was killed in combat in Afghanistan. Bell was born in London and moved to Los Angeles with her family at the young age of three. While studying biomedical engineering at UCLA, Bell ventured into modeling, which soon led to immediate recognition in both the United States and overseas. Building on her success as a model, she decided to pursue an acting career, which was launched soon thereafter. While working in television, Bell has also generated a loyal fan base with Hallmark Channel’s “The Good Witch” movie franchise, always among the highest-rated original movie premieres on the network. Starring as Cassandra “Cassie” Nightingale, Bell completed seven Original Movies in the franchise, including “The Good Witch,” “The Good Witch’s Garden,” “The Good Witch’s Gift,” “The Good Witch’s Family,” “The Good Witch’s Charm,” “The Good Witch’s Destiny” and “The Good Witch’s Wonder.” Other TV credits include Lifetime’s “Still Small Voices” and “Last Man Standing,” CBS’ “Company Town” and TNT’s “Good Morning Killer” as well as guest starring roles on “Law & Order: Special Victims Unit,” “Friends,” “Dream On” and “King & Maxwell.” Bell’s feature film credits include Universal’s mega-hit “Bruce Almighty” opposite Jim Carrey, as well as “Men of War,” and Netflix’s “The Do-Over” alongside Adam Sandler.