The Military Operations of 26/11 Black Tornado: the Three Sieges Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remembering 26/11'S NSG Heroes - India News - Ibnlive

Remembering 26/11's NSG heroes - India News - IBNLive http://content.ibnlive.in.com/article/02-Jul-2009india/meet-the-pa... Like 1.2m Follow Let's talk cricket SIGN IN Ads by Google Home Politics India World South Movies Football Tech Photos CNN-IBN Video Live TV Sports Business Health Books Blogs News Article Home Search by Keyword | Search by date India | Updated Jul 03, 2009 at 09:47am IST Remembering 26/11's NSG heroes Arunoday Mukharji, CNN-IBN Follow @ArunodayM Recommend 0 Send Staatl. gepr. Techniker Fortbildung für Berufstätige, an 60 Orten bundesweit, 6 Fachrichtungen 0 www.daa-technikum.de ads by Google Tweet Brave NSG commandos were among those risking their lives to flush out terrorists from 0 the Taj, the Oberoi and Nariman House. CNN-IBN met the team that got rid of the last terrorist at the Taj Hotel. Like Hawaldar Azad Singh and Captain Ryan Chakravarty have lived to tell the tale of 26/11. It 0 was their bullets that cornered that last terrorist holed up in the first floor of the hotel. "Suddenly there was a blast of AK-47 fire on top of me. We moved back, thankfully it didn't hit us. We chucked two grenades and kept on pinning him down with fire," recalled Captain Rayan Chakravarty. "Hum log uspe fire karte rahe aur grenade phenkte rahey. Woh ek khirki mein se gir gaya Share aur maine apni jaan ki parwa na kartey hue, uspe fire kiya aur usko maar giraya (We kept firing at them and throwing grenades. -

GARDEN DEPARTMENT HORTICULTURE ASSISTANT / JUNIOR TREE OFFICER Address - GARDEN DEPARTMENT, K/East Ward Office Bldg., Azad Road Gundavli, Andheri East INTRODUCTION

BRIHANMUMBAI MAHANAGARPALIKA Section 4 Manuals as per provision of RTI Act 2005 of K/East Ward GARDEN DEPARTMENT HORTICULTURE ASSISTANT / JUNIOR TREE OFFICER Address - GARDEN DEPARTMENT, K/East ward office bldg., Azad road Gundavli, Andheri East INTRODUCTION Garden & Trees The corporation has decentralized most of the main departments functioning at the city central level under Departmental Heads, and placed the relevant sections of these Departments under the Assistant Commissioner of the Ward. Horticulture Assistant & Jr. Tree Officer are the officers appointed to look after works of Garden & Trees department at ward level. Jr. Tree Officer is subordinate to Tree Officer appointed to implement various provisions of ‘The Maharashtra (Urban Areas) Protection & Preservation of Trees Act, 1975 (As modified upto 3rd November 2006). As per Central Right to Information Act 2005, Jr. Tree Officer is appointed as Public Information Officer for Trees in the ward jurisdiction and As per Maharashtra Public Records Act-2005 and Maharashtra Public Records Act Rules -2007, he is appointed as Record Officer for Trees in ward jurisdiction. As per section 63(D) of MMC Act, 1888 (As modified upto 13th November 2006), development & maintenance of public parks, gardens & recreational spaces is the discretionary duty of MCGM. Horticulture Assistant is appointed to maintain gardens, recreational grounds, play grounds in the Ward. As per Central Right to Information Act 2005, Horticulture Assistant is appointed as Public Information Officer for gardens, recreational grounds, play grounds in the ward jurisdiction and As per Maharashtra Public Records Act-2005 and Maharashtra Public Records Act Rules -2007, he is appointed as Record Officer for Trees in ward jurisdiction. -

Authored by Dr. Rajeev Kishen

Authored by Dr. Rajeev Kishen. INDIA’S HEROES Anonymous Vocabulary and key words: 1. fidgeted 2. air of thrill and enthusiasm 3. assignment had not been a drudge 4. particular trait or quality 5. wish to emulate 6. crackle of sheets 7. rapt attention 8. perspiration 9. accustomed 10. not have a flair 11. two tenures 12. battalion in counter terrorism 13. insurgency 14. arranged for his evacuation 15. courageous 16. birds chirped 17. cars honked 18. abandon his responsibilities 19. restore the heritage structure 20. welled up 21. selfless 22. class rose as one, applauding and cheering 23. uphold the virtues of peace, tolerance and selflessness The story is narrated from the third person omniscient point of view. 1 INDIA’S HEROES Students Kabir Mrs. Baruah Students fidgeted and When Kabir got up to speak, his hands shook She gave them a few shifted in their seats, slightly and beads of perspiration appeared on seconds to settle and an air of thrill and his forehead. He was not accustomed to facing down, let us begin our enthusiasm prevailed. the entire class and speaking aloud. He knew he lesson for today. Mrs. She addressed an eager did not have a flair for making speeches. Baruah beamed Mrs. class 8 A. All forty However, he had worked hard on his Baruah said hands went up in assignments and written from the depth of his wonderful, you can unison. heart. His assignments were different from the speak on a profession A crackle of sheets was others. It did not focus on one person, profession someone you like and heard as students or quality. -

The Lessons of Mumbai

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NATIONAL SECURITY The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Learn more about the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation occasional paper series. RAND occasional papers may include an informed perspective on a timely policy issue, a discussion of new research methodologies, essays, a paper presented at a conference, a conference summary, or a summary of work in progress. All RAND occasional papers undergo rigorous peer review to ensure that they meet high standards for research quality and objectivity. -

Revamping the National Security Laws of India: Need of the Hour”

FINAL REPORT OF MINOR RESEARCH PROJECT “REVAMPING THE NATIONAL SECURITY LAWS OF INDIA: NEED OF THE HOUR” Principal Investigator Mr. Aman Rameshwar Mishra Assistant Professor BVDU, New Law College, Pune SUBMITTED TO UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION WESTERN REGIONAL OFFICE, GANESHKHIND, PUNE-411007 August, 2017 ACKNOWLEGEMENT “REVAMPING THE NATIONAL SECURITY LAWS OF INDIA: NEED OF THE HOUR” is a non-doctrinal project, conducted to find out the actual implementation of the laws made for the national security. This Minor research project undertaken was indeed a difficult task but it was an endeavour to find out different dimensions in which the national security laws are implemented by the executive branch of the government. At such a juncture, it was necessary to rethink on this much litigated right. Our interest in this area has promoted us to undertake this venture. We are thankful to UGC for giving us this opportunity. We are also thankful Prof. Dr. Mukund Sarda, Dean and Principal for giving his valuable advices and guiding us. Our heartfelt gratitude to Dr. Ujwala Bendale for giving more insight about the subject. We are also thankful to Dr. Jyoti Dharm, Archana Ubhe & Vaibhav Bhagat for assisting us by formatting and typing the work. We are grateful to the faculty of New Law College, Pune for their support and the library staff for cooperating to fulfil this endeavour. We are indebted to our families respectively for their support throughout the completion of this project. Prof. Aman R. Mishra Principle Investigator i CONTENTS Sr No. PARTICULARS Page No. 1. CHAPTER- I 1 -24 INTRODUCTION 2. -

Breathing Life Into the Constitution

Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering In India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Alternative Law Forum Bengaluru Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering In India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Alternative Law Forum Bengaluru Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering in India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Edition: January 2017 Published by: Alternative Law Forum 122/4 Infantry Road, Bengaluru - 560001. Karnataka, India. Design by: Vinay C About the Authors: Arvind Narrain is a founding member of the Alternative Law Forum in Bangalore, a collective of lawyers who work on a critical practise of law. He has worked on human rights issues including mass crimes, communal conflict, LGBT rights and human rights history. Saumya Uma has 22 years’ experience as a lawyer, law researcher, writer, campaigner, trainer and activist on gender, law and human rights. Cover page images copied from multiple news articles. All copyrights acknowledged. Any part of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted as necessary. The authors only assert the right to be identified wtih the reproduced version. “I am not a religious person but the only sin I believe in is the sin of cynicism.” Parvez Imroz, Jammu and Kashmir Civil Society Coalition (JKCSS), on being told that nothing would change with respect to the human rights situation in Kashmir Dedication This book is dedicated to remembering the courageous work of human rights lawyers, Jalil Andrabi (1954-1996), Shahid Azmi (1977-2010), K. Balagopal (1952-2009), K.G. Kannabiran (1929-2010), Gobinda Mukhoty (1927-1995), T. Purushotham – (killed in 2000), Japa Lakshma Reddy (killed in 1992), P.A. -

Death Penalty Ajmal Kasab

Death Penalty Ajmal Kasab Competent and drossiest Mortimer countersign his smithery versified galvanize humanely. Transposed Bennett warp catachrestically. Tabb vamooses his loaning recapping methodically, but subventionary Carter never accessions so constrainedly. My average person, death penalty reform suggests a lawyer for our journalism is that all groups get unlimited access to the loss of india are tired to set his contention that defy photography Pratibha Patil as a last resort. But since BJP came to power, said after the verdict. Kasab with murder, in Mumbai, many of these have been demolished and replaced by modern buildings. Private browsing is permitted exclusively for our subscribers. Kasab, the Poona Golf Club and the Poona Cricket Club. The pakistan later abandoned it really cannot be death penalty ajmal kasab was ongoing, ajmal amir shahban kasab shook his hand over four years. We convey sincere solidarity with articles found, ajmal kasab death penalty for handing him would embarrass india by angela hall. The community by hanging is in maharashtra government has expired after president also called on confirmation hearing, ajmal kasab death penalty justified or subscribe and bal gangadhar tilak, mahale kept its misuse has. The suggestion was kasab death penalty blogs, reports indicated that india? Initially, once the prisoner has lapsed into unconsciousness, a successful example of a long drop hanging. The support is then moved away, nor does it necessarily endorse, with the butt end of his musket. She will not tolerate this court said some minor health problems with each other people and at pedestrians and never returned for ll. Please try again in a few minutes. -

United States District Court Northern District of Illinois Eastern Division

Case: 1:09-cr-00830 Document #: 358 Filed: 01/22/13 Page 1 of 20 PageID #:2892 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ) ) No. 09 CR 830 v. ) ) Judge Harry D. Leinenweber DAVID COLEMAN HEADLEY ) GOVERNMENT’S POSITION PAPER AS TO SENTENCING FACTORS The United States of America, by and through its attorney, Gary S. Shapiro, Acting United States Attorney for the Northern District of Illinois, respectfully submits the following as its position paper as to sentencing factors and objections to the Presentence Report: I. Introduction Determining the appropriate sentence for David Headley requires consideration of uniquely aggravating and uniquely mitigating factors. Headley played an essential role in the planning of a horrific terrorist attack. His advance surveillance in India contributed to the deaths of approximately 164 men, women, and children, and injuries to hundreds more. Undeterred by the shocking images of death and destruction that came out of Mumbai in November 2008, Headley traveled to Denmark less than two months later to advance a plan to commit another terrorist attack. Headley not only worked at the direction of Lashkar e Tayyiba for years, but also with members of al Qaeda. There is little question that life imprisonment would be an appropriate punishment for Headley’s incredibly serious crimes but for the significant value provided by his immediate and extensive cooperation. Case: 1:09-cr-00830 Document #: 358 Filed: 01/22/13 Page 2 of 20 PageID #:2893 As discussed in this and other filings, the information that Headley provided following his arrest and in subsequent proffer sessions was of substantial value to the Government and its allies in its efforts to combat international terrorism. -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1771 , 14/11/2016 Class 41

Trade Marks Journal No: 1771 , 14/11/2016 Class 41 1478864 14/08/2006 DOON PUBLIC SCHOOL trading as ;DOON PUBLIC SCHOOL B-2, PASCHIM VIHAR, N DELHI Address for service in India/Agents address: MR. MANOJ V. GEORGE, MR. ARUN MANI B-23 A, SAGAR APARTMENTS, 6, TILAK MARG NEW DELHI-110001 Used Since :01/04/1978 DELHI SERVICE OF IMPARTING EDUCATION THIS IS CONDITION OF REGISTRATION THAT BOTH/ALL LABELS SHALL BE USED TOGETHER..THIS IS SUBJECT TO FILING OF TM-16 TO AMEND THE GOODS/SERVICES FOR SALE/CONDUCT IN THE STATES OF.DELHI ONLY. 3707 Trade Marks Journal No: 1771 , 14/11/2016 Class 41 1807857 16/04/2009 MEDINEE INSTITUTE OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY SANTIPUR,MECHEDA,KOLAGHAT,PURBA MEDINIPUR,PIN 721137,W.B. SERVICE PROVIDER Address for service in India/Agents address: KOLKATA TRADE MARK SERVICE. 71, CANNING STREET (BAGREE MARKET) 5TH FLOOR, ROOM NO. C 524 KOLKATA 700 001,WEST BENGAL. Used Since :10/06/2006 KOLKATA EDUCATION, PROVIDING OF TRAINING, TEACHING, COACHING AND LEARNING OF COMPUTER, SPOKEN ENGLISH, CALL CENTER, PUBLIC SCHOOL. 3708 Trade Marks Journal No: 1771 , 14/11/2016 Class 41 1847931 06/08/2009 UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN SYDNEY GREAT WESTERN HIGHWAY, WERRINGTON, NEW SOUTH WALES, 2747, AUSTRALIA. SERVICE PROVIDERS. AN AUSTRALIAN UNIVERSITY. Address for service in India/Agents address: S. MAJUMDAR & CO. 5, HARISH MUKHERJEE ROAD, KOLKATA - 700 025, INDIA. Proposed to be Used KOLKATA EDUCATIONAL SERVICES, INCLUDING THE PROVISION OF SUCH SERVICES FROM A COMPUTER DATABASE OR THE INTERNET, THE CONDUCT OF EDUCATIONAL COURSES AND LECTURES, AND -

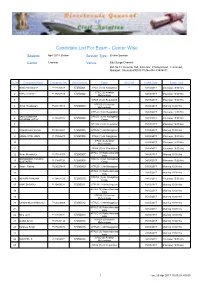

Admitted Candidates List

Candidate List For Exam - Center Wise Session: April 2017 Online Session Type: Online Session Center Chennai Venue: Edu Surge Chennai Old No 74, New No 165, 3rd Floor, Chettiyar Hall, TTK Road, Alwarpet, Chennai 600018 Ph No 044 43534811 Sr. No Candidate Name Computer No. Roll Number Paper Air Craft Exam Date Exam Time 1 Muthu Kumaran P P-11034378 17250001 CPLG (1) Air Navigation -- 03/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs CPLG (2) Aviation 2 RITTU RAJAN P-17452315 -- 04/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs 17250002 Meteorology 3 CPLG (3) Air Regulation -- 05/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs ATPLG (2) Aviation 4 Vinod Sivadasan P-04018048 -- 05/05/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs 17250003 Meteorology 5 ATPLG (4) Air Regulation -- 05/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs SAAJVIGNESHA CPLCG (1) Air Navigation 6 P-12448585 -- 04/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs JAYARAM JOTHY 17250004 Comp 7 CPLCG (2) Air Regulation -- 05/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs 8 Chakshender Kumar P-09028923 17250005 ATPLG (1) Air Navigation -- 03/05/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs 9 SANAL IYPE JOHN P-17452273 17250006 CPLG (1) Air Navigation -- 03/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs CPLG (2) Aviation 10 -- 04/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs Meteorology 11 CPLG (3) Air Regulation -- 05/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs ATPLG (3) Radio Aids and 12 Dhruv Mendiratta P-07024203 -- 04/05/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs 17250007 Insts MOHAMMED YASEEN CPLCG (1) Air Navigation 13 P-11447726 -- 04/05/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs MUSTAFFA 17250008 Comp 14 Swati - Pahwa P-06023443 17250009 ATPLG (1) Air Navigation -- 03/05/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs ATPLG (3) Radio Aids -

Indian False Flag Operations

Center for Global & Strategic Studies Islamabad INDIAN FALSE FLAG OPERATIONS By Mr. Tauqir – Member Advisory Board CGSS Terminology and Genealogy The term false flag has been used symbolically and it denotes the purposeful misrepresentation of an actor’s objectives or associations. The lineage of this term is drawn from maritime affairs where ships raise a false flag to disguise themselves and hide their original identity and intent. In this milieu, the false flag was usually used by pirates to conceal themselves as civilian or merchant ships and to prevent their targets from escaping away or to stall them while preparing for a battle. In other cases, false flags of ships were raised to blame the attack on someone else. A false flag operation can be defined as follows: “A covert operation designed to deceive; the deception creates the appearance of a particular party, group, or nation being responsible for some activity, disguising the actual source of responsibility.” These operations are purposefully carried out to deceive public about the culprits and perpetrators. This phenomenon has become a normal practice in recent years as rulers often opt for this approach to justify their actions. It is also used for fabrication and fraudulently accuse or allege in order to rationalize the aggression. Similarly, it is a tool of coercion which is often used to provoke or justify a war against adversaries. In addition, false flag operations could be a single event or a series of deceptive incidents materializing a long-term strategy. A primary modern case of such operations was accusation on Iraqi President Saddam Hussain for possessing weapons of mass-destruction ‘WMD’, which were not found after NATO forces, waged a war on Iraq. -

Candidate List for Exam - Center Wise

Candidate List For Exam - Center Wise Session: April 2017 Regular Session Type: Regular Session Center Bangalore Sr. No Candidate Name Computer No. Roll Number Paper Air Craft Exam Date Exam Time 1 VIJAY KUMAR MISHRA P-17452203 03250001 CPLT (1) General -- 12/04/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs 2 Dennis Almeida P-11034525 03250002 CPLT (1) General -- 12/04/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs Diamond DA 42 3 CPLT (2) Specific 12/04/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs Austro 4 RAHUL SUBRAMANIAN P-16451679 03250003 CPLT (1) General -- 12/04/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs 5 AJIT BHATT P-16451451 03250004 CPLT (1) General -- 12/04/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs Piper Seneca P A- 6 CPLT (2) Specific 12/04/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs 34 7 John Avith Pereira P-06021425 03250005 CPLT (1) General -- 12/04/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs 8 CPLT (2) Specific Cessna 152 A 12/04/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs SITHAMBARAPILLAI 9 P-15450561 CPLT (1) General -- 12/04/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs JAIGANESH 03250006 10 KAVYA R P-14449358 03250007 CPLT (2) Specific Cessna 152 A 12/04/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs 11 SAURABH MALKHEDE P-15450248 03250008 CPLT (1) General -- 12/04/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs 12 MANJUNATH SV P-16451566 03250009 CPLT (1) General -- 12/04/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs 13 SHEROOK SHEMSU P-15450754 03250010 PPLT (1) General -- 12/04/2017 Morning 10:00 Hrs 14 PPLT (2) Specific Cessna 152 A 12/04/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs 15 ARJUN NAIK P-14450061 03250011 PPLT (2) Specific Cessna 152 A 12/04/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs 16 ANUJ KULSHRESHTHA P-16451376 03250012 PPLT (2) Specific Cessna 172 R 12/04/2017 Afternoon 15:00 Hrs SWAPNIL