Sport and Leisure in Rome from the Fascist Years to the Olympic Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Il 6 Nazioni. All’Olimpico

IL 6 NAZIONI. ALL’OLIMPICO. ITALIA VS FRANCIA 3 FEBBRAIO ITALIA VS GALLES 23 FEBBRAIO ITALIA VS IRLANDA 16 MARZO © 2012 adidas AG. adidas, the 3-Bars logo and the 3-Stripes mark are registered trademarks of the adidas Group. trademarks registered mark are and the 3-Stripes logo adidas, the 3-Bars © 2012 adidas AG. l’italia del rugby veste adidas Indossa la nuova maglia ufficiale della Nazionale Italiana di Rugby e fai sentire la tua voce su vocidelrugby.com adidas.com M0203_150x210_MediaGuide_AD_Mischia.indd 1 15/01/13 14:31 INDICE Il saluto del Presidente . 2 Il saluto del Presidente del CONI . 4 Il saluto del Sindaco di Roma . 5 La Federazione Italiana Rugby . 6 Il calendario del 6 Nazioni 2013 . 7 Gli arbitri del 6 Nazioni 2013 . 8 La storia del Torneo . 9 L’Albo d’oro del Torneo . 11 Il Torneo dal 2000 ad oggi . 13 I tabellini dell’Italia nel 6 Nazioni . 26 Le avversarie dell’Italia Francia . 38 Scozia . 40 Galles . 42 Inghilterra . 44 Irlanda . 46 Italia . 48 Lo staff azzurro . 50 Il gruppo azzurro . 57 Statistiche . 74 Programma stampa Nazionale Italiana . 84 Gli alberghi dell’Italia . 86 Contatti utili . 86 Calendario 6 Nazioni 2013 Femminile . 88 Le Azzurre e lo Staff . 89 Calendario 6 Nazioni 2013 Under 20 . 92 Gli Azzurrini e lo Staff . 93 media guide 2013 1 Il saluto del Presidente E’ per me un grande piacere rivolgere un caloroso saluto, a nome mio personale e di tutta la Federazione Italiana Rugby, al pubblico, agli sponsor, ai media che seguiranno gli Azzurri nel corso dell’RBS 6 Nazioni 2013. -

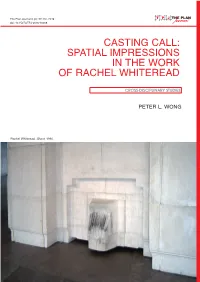

Casting Call: Spatial Impressions in the Work of Rachel Whiteread

The Plan Journal 0 (0): 97-110, 2016 doi: 10.15274/TPJ-2016-10008 CASTING CALL: SPATIAL IMPRESSIONS IN THE WORK OF RACHEL WHITEREAD CROSS-DISCIPLINARY STUDIES PETER L. WONG Rachel Whiteread, Ghost, 1990. Casting Call: Spatial Impressions in the Work of Rachel Whiteread Peter L. Wong ABSTRACT - For more than 20 years, Rachel Whiteread has situated her sculpture inside the realm of architecture. Her constructions elicit a connection between: things and space, matter and memory, assemblage and wholeness by drawing us toward a reciprocal relationship between objects and their settings. Her chosen means of casting solids from “ready- made” objects reflect a process of visual estrangement that is dependent on the original artifact. The space beneath a table, the volume of a water tank, or the hollow undersides of a porcelain sink serve as examples of a technique that aligns objet-trouvé with a reverence for the everyday. The products of this method, now rendered as space, acquire their own autonomous presence as the formwork of things is replaced by space as it solidifies and congeals. The effect is both reliant and independent, familiar yet strange. Much of the writing about Whiteread’s work occurs in the form of art criticism and exhibition reviews. Her work is frequently under scrutiny, fueled by the popular press and those holding strict values and expectations of public art. Little is mentioned of the architectural relevance of her process, though her more controversial pieces are derived from buildings themselves – e,g, the casting of surfaces (Floor, 1995), rooms (Ghost, 1990 and The Nameless Library, 2000), or entire buildings (House, 1993). -

The Influence of International Town Planning Ideas Upon Marcello Piacentini’S Work

Bauhaus-Institut für Geschichte und Theorie der Architektur und Planung Symposium ‟Urban Design and Dictatorship in the 20th century: Italy, Portugal, the Soviet Union, Spain and Germany. History and Historiography” Weimar, November 21-22, 2013 ___________________________________________________________________________ About the Internationality of Urbanism: The Influence of International Town Planning Ideas upon Marcello Piacentini’s Work Christine Beese Kunsthistorisches Institut – Freie Universität Berlin – Germany [email protected] Last version: May 13, 2015 Keywords: town planning, civic design, civic center, city extension, regional planning, Italy, Rome, Fascism, Marcello Piacentini, Gustavo Giovannoni, school of architecture, Joseph Stübben Abstract Architecture and urbanism generated under dictatorship are often understood as a materialization of political thoughts. We are therefore tempted to believe the nationalist rhetoric that accompanied many urban projects of the early 20th century. Taking the example of Marcello Piacentini, the most successful architect in Italy during the dictatorship of Mussolini, the article traces how international trends in civic design and urban planning affected the architect’s work. The article aims to show that architectural and urban form cannot be taken as genuinely national – whether or not it may be called “Italian” or “fascist”. Concepts and forms underwent a versatile transformation in history, were adapted to specific needs and changed their meaning according to the new context. The challenge is to understand why certain forms are chosen in a specific case and how they were used to create displays that offer new modes of interpretation. The birth of town planning as an architectural discipline When Marcello Piacentini (1881-1960) began his career at the turn of the 20th century, urban design as a profession for architects was a very young discipline. -

Falda's Map As a Work Of

The Art Bulletin ISSN: 0004-3079 (Print) 1559-6478 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art Sarah McPhee To cite this article: Sarah McPhee (2019) Falda’s Map as a Work of Art, The Art Bulletin, 101:2, 7-28, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 Published online: 20 May 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 79 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art sarah mcphee In The Anatomy of Melancholy, first published in the 1620s, the Oxford don Robert Burton remarks on the pleasure of maps: Methinks it would please any man to look upon a geographical map, . to behold, as it were, all the remote provinces, towns, cities of the world, and never to go forth of the limits of his study, to measure by the scale and compass their extent, distance, examine their site. .1 In the seventeenth century large and elaborate ornamental maps adorned the walls of country houses, princely galleries, and scholars’ studies. Burton’s words invoke the gallery of maps Pope Alexander VII assembled in Castel Gandolfo outside Rome in 1665 and animate Sutton Nicholls’s ink-and-wash drawing of Samuel Pepys’s library in London in 1693 (Fig. 1).2 There, in a room lined with bookcases and portraits, a map stands out, mounted on canvas and sus- pended from two cords; it is Giovanni Battista Falda’s view of Rome, published in 1676. -

Watergate Landscaping Watergate Innovation

Innovation Watergate Watergate Landscaping Landscape architect Boris Timchenko faced a major challenge Located at the intersections of Rock Creek Parkway and in creating the interior gardens of Watergate as most of the Virginia and New Hampshire Avenues, with sweeping views open grass area sits over underground parking garages, shops of the Potomac River, the Watergate complex is a group of six and the hotel meeting rooms. To provide views from both interconnected buildings built between 1964 and 1971 on land ground level and the cantilivered balconies above, Timchenko purchased from Washington Gas Light Company. The 10-acre looked to the hanging roof gardens of ancient Babylon. An site contains three residential cooperative apartment buildings, essential part of vernacular architecture since the 1940s, green two office buildings, and a hotel. In 1964, Watergate was the roofs gained in popularity with landscapers and developers largest privately funded planned urban renewal development during the 1960s green awareness movement. At Watergate, the (PUD) in the history of Washington, DC -- the first project to green roof served as camouflage for the underground elements implement the mixed-use rezoning adopted by the District of of the complex and the base of a park-like design of pools, Columbia in 1958, as well as the first commercial project in the fountains, flowers, open courtyards, and trees. USA to use computers in design configurations. With both curvilinear and angular footprints, the configuration As envisioned by famed Italian architect Dr. Luigi Moretti, and of the buildings defines four distinct areas ranging from public, developed by the Italian firm Società Generale Immobiliare semi-public, and private zones. -

Gerry Mulligan Discography

GERRY MULLIGAN DISCOGRAPHY GERRY MULLIGAN RECORDINGS, CONCERTS AND WHEREABOUTS by Gérard Dugelay, France and Kenneth Hallqvist, Sweden January 2011 Gerry Mulligan DISCOGRAPHY - Recordings, Concerts and Whereabouts by Gérard Dugelay & Kenneth Hallqvist - page No. 1 PREFACE BY GERARD DUGELAY I fell in love when I was younger I was a young jazz fan, when I discovered the music of Gerry Mulligan through a birthday gift from my father. This album was “Gerry Mulligan & Astor Piazzolla”. But it was through “Song for Strayhorn” (Carnegie Hall concert CTI album) I fell in love with the music of Gerry Mulligan. My impressions were: “How great this man is to be able to compose so nicely!, to improvise so marvellously! and to give us such feelings!” Step by step my interest for the music increased I bought regularly his albums and I became crazy from the Concert Jazz Band LPs. Then I appreciated the pianoless Quartets with Bob Brookmeyer (The Pleyel Concerts, which are easily available in France) and with Chet Baker. Just married with Danielle, I spent some days of our honey moon at Antwerp (Belgium) and I had the chance to see the Gerry Mulligan Orchestra in concert. After the concert my wife said: “During some songs I had lost you, you were with the music of Gerry Mulligan!!!” During these 30 years of travel in the music of Jeru, I bought many bootleg albums. One was very important, because it gave me a new direction in my passion: the discographical part. This was the album “Gerry Mulligan – Vol. 2, Live in Stockholm, May 1957”. -

Palermo, City of Syncretism: Recovering a Complex

Proceedings of the 3r International Conference on Best Practices in World Heritage: Integral Actions Menorca, Spain, 2-5 May 2018 PALERMO, CITY OF SYNCRETISM: RECOVERING A COMPLEX HISTORIC CENTRE HELPED BY AN AWARE LOCAL COMMUNITY Palermo, ciudad sincrética: recuperar un centro histórico complejo con la ayuda de una comunidad local consciente Giorgio Faraci (1) (1) Università degli Studi di Palermo - DARCH Dipartimento di Architettura, Palermo, Italia, [email protected] ABSTRACT The Italian site of Arab-Norman Palermo and the Cathedral Churches of Cefalú and Monreale was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2015 as an example of a social- cultural syncretism between Western, Islamic and Byzantine cultures. Palermo has maintained its identity over the centuries as a complex and multicultural site. In 1993 the local government of Palermo, supported by the Sicilian Region with specific Laws and funds, launched a process of regeneration of the historic centre, restoring public monuments as well as encouraging recovery of private houses. A specific planning instrument such as the Piano Particolareggiato Esecutivo (PPE) was implemented and a special office was established to coordinate activities and funding. Local community developed a pro-active attitude over the years, demanding local government to promote more cooperation and coordination between the different stakeholders involved in the recovery process. The civil society emphasised the need to intervene not only on the urban and building fabric but also on the social one, starting from the weakest sections of the population. The support of civil society, with its bottom up approach, and the strong political will of local government, determined in the regeneration of the historic centre, made possible to speed up the process. -

The Six Nations Rugby Song Book Free Download

THE SIX NATIONS RUGBY SONG BOOK FREE DOWNLOAD Huw James | 64 pages | 31 Dec 2010 | Y Lolfa Cyf | 9781847712066 | English | Talybont, United Kingdom Six Nations Championship Retrieved 29 September Categories : Six Nations Championship establishments in Europe Rugby union competitions in Europe for national teams Recurring sporting events established in International rugby union competitions hosted by England International rugby union competitions hosted by France International rugby union competitions hosted by Ireland International rugby union competitions hosted by Scotland International rugby union competitions hosted by Wales International rugby union competitions hosted by Italy England national rugby union team France national rugby union team Ireland national rugby union team The Six Nations Rugby Song Book national rugby union team Wales national rugby union team Italy national rugby union team. Rugby union in Italy. Retrieved 6 January Entrepreneur, 27, who forced himself on woman, 33, at Royal Festival Hall Christmas bash is told to expect It was surreal and everything that rugby and team sport is not, edgy, individualistic. Library of Wales. John Leslie thanks his supporters and says he will be spending time 'putting his family back together again' Within the mahogany base is a concealed drawer which contains six alternative finialseach a silver replica of one of the team emblems, which can be screwed on the detachable lid. The Guinness Six Nations logo. And The Six Nations Rugby Song Book the Irish go one better when playing in Dublin — two anthems and song. The first ever Home Nations International Championship was played in National anthems are relatively young but then a The Six Nations Rugby Song Book in the sense of a geographic area with a single government is a relatively new concept. -

The Watergate Project: a Contrapuntal Multi-Use Urban Complex in Washington, Dc

THE WATERGATE PROJECT: A CONTRAPUNTAL MULTI-USE URBAN COMPLEX IN WASHINGTON, DC Adrian Sheppard, FRAIC Professor of Architecture McGill University Montreal Canada INTRODUCTION Watergate is one of North America’s most imaginative and powerful architectural ensembles. Few modern projects of this scale and inventiveness have been so fittingly integrated within an existing and well-defined urban fabric without overpowering its neighbors, or creating a situation of conflict. Large contemporary urban interventions are usually conceived as objects unto themselves or as predictable replicas of their environs. There are, of course, some highly successful exceptions, such as New York’s Rockefeller Centre, which are exemplars of meaningful integration of imposing projects on an existing city, but these are rare. By today’s standards where significance in architecture is measured in terms of spectacle and flamboyance, Watergate is a dignified and rigorous urban project. Neither conventional as an urban design project, nor radical in its housing premise, it is nevertheless as provocative as anything in Europe. Because Moretti grasped the essence of Washington so accurately, he was able to bring to the city a new vision of urbanity. Watergate would prove to be an unequivocally European import grafted unto a typical North-American city, its most remarkable and successful characteristic being its relationship to its immediate context and the city in general. As an urban intervention, Watergate is an inspiring example of how a Roman architect, Luigi Moretti, succeeded in introducing a project of considerable proportions in the fabric of Washington, a city he had never visited before he received the commission. 1 Visually and symbolically, the richness of the traditional city is derived from the fact that there exists a legible distinction and balance between urban fabric and urban monument. -

PDF Download

OPEN ACCESS CC BY 4.0 ©The Authors. The contents of this volume are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. For a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. This license allows for copying and adapting any part of the work for personal and commercial use, providing appropriate credit is clearly stated. ISSN: 2532-3512 How to cite this volume: Please use AJPA as abbreviation and ‘Archeostorie. Journal of Public Archaeology’ as full title. Published by: Center for Public Archaeology Studies ‘Archeostorie’ - cultural association via Enrico Toti 14, 57128 Livorno (ITALY) / [email protected] First published 2018. Archeostorie. Journal of Public Archaeology is registered with the Court of Livorno no. 2/2017 of January 24, 2017. ARCHEOSTORIE TM VOLUME 2 / 2018 www.archeostoriejpa.eu Editor in chief Cinzia Dal Maso - Center for Public Archaeology Studies ‘Archeostorie’ Luca Peyronel - University of Milan Advisory board Chiara Bonacchi - University of Stirling Luca Bondioli - Luigi Pigorini National Museum of Prehistory and Ethnography, Rome Giorgio Buccellati - University of California at Los Angeles Aldo Di Russo - Unicity, Rome Dora Galanis - Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports Filippo Maria Gambari - Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage Peter Gould - University of Pennsylvania and The American University of Rome Christian Greco - Egyptian Museum, Turin Richard -

Mussolini's Ambiguous and Opportunistic Conception of Romanità

“A Mysterious Revival of Roman Passion”: Mussolini’s Ambiguous and Opportunistic Conception of Romanità Benjamin Barron Senior Honors Thesis in History HIST-409-02 Georgetown University Mentored by Professor Foss May 4, 2009 “A Mysterious Revival of Roman Passion”: Mussolini’s Ambiguous and Opportunistic Conception of Romanità CONTENTS Preface and Acknowledgments ii List of Illustrations iii Introduction 1 I. Mussolini and the Power of Words 7 II. The Restrained Side of Mussolini’s Romanità 28 III. The Shift to Imperialism: The Second Italo-Ethiopian War 1935 – 1936 49 IV. Romanità in Mussolini’s New Roman Empire 58 Conclusion 90 Bibliography 95 i PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I first came up with the topic for this thesis when I visited Rome for the first time in March of 2008. I was studying abroad for the spring semester in Milan, and my six-month experience in Italy undoubtedly influenced the outcome of this thesis. In Milan, I grew to love everything about Italy – the language, the culture, the food, the people, and the history. During this time, I traveled throughout all of Italian peninsula and, without the support of my parents, this tremendous experience would not have been possible. For that, I thank them sincerely. This thesis would not have been possible without a few others whom I would like to thank. First and foremost, thank you, Professor Astarita, for all the time you put into our Honors Seminar class during the semester. I cannot imagine how hard it must have been to read all of our drafts so intently. Your effort has not gone unnoticed. -

Download All Beautiful Sites

1,800 Beautiful Places This booklet contains all the Principle Features and Honorable Mentions of 25 Cities at CitiesBeautiful.org. The beautiful places are organized alphabetically by city. Copyright © 2016 Gilbert H. Castle, III – Page 1 of 26 BEAUTIFUL MAP PRINCIPLE FEATURES HONORABLE MENTIONS FACET ICON Oude Kerk (Old Church); St. Nicholas (Sint- Portugese Synagoge, Nieuwe Kerk, Westerkerk, Bible Epiphany Nicolaaskerk); Our Lord in the Attic (Ons' Lieve Heer op Museum (Bijbels Museum) Solder) Rijksmuseum, Stedelijk Museum, Maritime Museum Hermitage Amsterdam; Central Library (Openbare Mentoring (Scheepvaartmuseum) Bibliotheek), Cobra Museum Royal Palace (Koninklijk Paleis), Concertgebouw, Music Self-Fulfillment Building on the IJ (Muziekgebouw aan 't IJ) Including Hôtel de Ville aka Stopera Bimhuis Especially Noteworthy Canals/Streets -- Herengracht, Elegance Brouwersgracht, Keizersgracht, Oude Schans, etc.; Municipal Theatre (Stadsschouwburg) Magna Plaza (Postkantoor); Blue Bridge (Blauwbrug) Red Light District (De Wallen), Skinny Bridge (Magere De Gooyer Windmill (Molen De Gooyer), Chess Originality Brug), Cinema Museum (Filmmuseum) aka Eye Film Square (Max Euweplein) Institute Musée des Tropiques aka Tropenmuseum; Van Gogh Museum, Museum Het Rembrandthuis, NEMO Revelation Photography Museums -- Photography Museum Science Center Amsterdam, Museum Huis voor Fotografie Marseille Principal Squares --Dam, Rembrandtplein, Leidseplein, Grandeur etc.; Central Station (Centraal Station); Maison de la Berlage's Stock Exchange (Beurs van