Equine Science Breeding and Stud Management, Writtle College and the University of Essex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EQUUS Film Festival 2016 – GUEST ON-LINE Please Be Polite and Be in Your Seat at the Start Time for the BLOCK of the Film Or Films You Wish to Screen

EQUUS Film Festival 2016 – GUEST ON-LINE Please be polite and be in your seat at the start time for the BLOCK of the film or films you wish to screen. ALL Times Are Subject to Change Without Notice – We reserve the RIGHT to substitute Films Featured Trailers: Apple Of My Eye – Trailer PREMIER from Sony Pictures Theater 1 – Friday – 12:00 p.m. Film Block – Film # 1 Theater 1 – Saturday – 12:00 p.m. Film Block – Film # 3 Lobby Loop Directed by: Castille Landon A young girl struggles after a traumatic horse riding accident causes her to lose her eyesight. CHARLES, the head trainer of Southeastern Guide Dogs, trains Apple, a miniature horse, to be her companion and surrogate eyes Writer: Castille Landon / Starring: Amy Smart, AJ Michalka, Burt Reynolds Horsepower: The Slaughter & Rescue of American Horses – USA Theater 2 – Saturday – 8:15 p.m. Film Block – Film # 1 Lobby Loop 06:34 Min / Directed by: Ry Wardwell 17 - Equestrian Documentary – Mini Trailer: http://www.horsepowerthemovie.com/ Horse auctioneers, rescues and ranchers battle each other to protect or slaughter horses that no longer have homes. While the struggle to protect wild horses also continues, "Horsepower" introduces us to the key issues, the auctions, and the “kill buyers” that are fueling the little-known, nationwide massacre of the American horse. Li’l Herc – Portugal Theater 1 – Friday – 12:00 p.m. Film Block – Film # 2 Theater 1 – Saturday – 12:00 p.m. Film Block – Film # 2 Lobby Loop 3:00 min / by Beatrice Bulteau & Suzanne Kopp-Moskow Trailer: http://www.lilhercworld.com/ Li'l Herc is based on a live Lusitano ("Hercules"); created for the enjoyment of folks of all ages by Suzanne Kopp-Moskow and Beatrice Bulteau. -

National Hunt Grade 1S 200 OLBG DAVID NICHOLSON Contest

DATA BOOK STAKES RESULTS National Hunt Grade 1s 200 OLBG DAVID NICHOLSON contest. This daughter of King’s UN DE SCEAUX b g 2008 (out of the Irish 1,000 Guineas winner MARES’ HURDLE G1 Theatre had finished a fine second to Classic Park) hasn’t been widely used Pampapaul Yellow God Quevega in the 2014 Mares’ Hurdle Pampalina in France, to the extent that he has CHELTENHAM. Mar 10. 4yo+f. 20f. Pampabird and she again looked destined to play Wood Grouse Celtic Ash only 120 foals in his first four crops. 1. GLENS MELODY (IRE) 7 11-5 £56,270 French Bird b m by King’s Theatre - Glens Music (Orchestra) second fiddle to a stablemate in DENHAM RED b 92 He is based nowadays at Haras Giboulee Northern Dancer 2015, when she came to the final Victory Chant des Granges and his fee in 2015 is O- Ms Fiona McStay B- Mrs F. McStay Nativelee TR- W. P. Mullins flight four lengths adrift of Annie Native Berry Ribero only 1,500. His best representative 2. Polly Peachum (IRE) 7 11-5 £21,200 Power. However, Annie Power Noble Native on the Flat has been Dance In The b m by Shantou - Miss Denman (Presenting) Kaldoun Caro crashed to the ground and Glens Katana Park, a Group-placed Listed winner. O- Lady Tennant B- C. O’Flynn April Night Melody gamely came out on top in a My Destiny Chaparral Douvan, though, was bred with a TR- Nicky Henderson Carmelite 3. Bitofapuzzle (GB) 7 11-5 £10,610 three-way finish. -

April 4-6 Contents

MEDIA GUIDE #TheWorldIsWatching APRIL 4-6 CONTENTS CHAIRMAN’S WELCOME 3 2018 WINNING OWNER 50 ORDER OF RUNNING 4 SUCCESSFUL OWNERS 53 RANDOX HEALTH GRAND NATIONAL FESTIVAL 5 OVERSEAS INTEREST 62 SPONSOR’S WELCOME 8 GRAND NATIONAL TIMELINE 64 WELFARE & SAFETY 10 RACE CONDITIONS 73 UNIQUE RACE & GLOBAL PHENOMENON 13 TRAINERS & JOCKEYS 75 RANDOX HEALTH GRAND NATIONAL ANNIVERSARIES 15 PAST RESULTS 77 ROLL OF HONOUR 16 COURSE MAP 96 WARTIME WINNERS 20 RACE REPORTS 2018-2015 21 2018 WINNING JOCKEY 29 AINTREE JOCKEY RECORDS 32 RACECOURSE RETIRED JOCKEYS 35 THIS IS AN INTERACTIVE PDF MEDIA GUIDE, CLICK ON THE LINKS TO GO TO THE RELEVANT WEB AND SOCIAL MEDIA PAGES, AND ON THE GREATEST GRAND NATIONAL TRAINERS 37 CHAPTER HEADINGS TO TAKE YOU INTO THE GUIDE. IRISH-TRAINED WINNERS 40 THEJOCKEYCLUB.CO.UK/AINTREE TRAINER FACTS 42 t @AINTREERACES f @AINTREE 2018 WINNING TRAINER 43 I @AINTREERACECOURSE TRAINER RECORDS 45 CREATED BY RACENEWS.CO.UK AND TWOBIRD.CO.UK 3 CONTENTS As April approaches, the team at Aintree quicken the build-up towards the three-day Randox Health Grand National Festival. Our first port of call ahead of the 2019 Randox welfare. We are proud to be at the forefront of Health Grand National was a media visit in the racing industry in all these areas. December, the week of the Becher Chase over 2019 will also be the third year of our the Grand National fences, to the yard of the broadcasting agreement with ITV. We have been fantastically successful Gordon Elliott to see delighted with their output and viewing figures, last year’s winner Tiger Roll being put through not only in the UK and Ireland, but throughout his paces. -

Moonshine Memories Looks to Recall Top Form in Raven

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 20, 2018 LITTLES CARRY ON WITH BRAINS AND CLASS MOONSHINE MEMORIES by Jessica Martini LOOKS TO RECALL TOP When Marvin Little, Jr. passed away in July of 2017, the legendary horseman left one goal unfulfilled. The breeder of FORM IN RAVEN RUN 1991 GI Preakness S. and GI Belmont S. winner Hansel wanted that missing jewel in the Triple Crown. A year plus later and Little=s daughters Teresa and Marilyn hope to accomplish that dream on behalf of their late father. The sisters will take a first step in their mission with their first consignment under the Little=s Bloodstock banner at the Fasig-Tipton October Sale. AThe one dream my father had, he won the Preakness and he won the Belmont, he won the Tremont and the Breeders= Cup, but he never won the Kentucky Derby,@ Teresa Little said. AAt my father=s funeral, I sang >My Old Kentucky Home,= and people said that wasn=t a good thing to do. But it was for me because it=s the only thing my father wanted to win. He wanted to breed or sell the winner of the Kentucky Derby.@ Cont. p3 IN TDN EUROPE TODAY Moonshine Memories | Benoit GOSDEN HOLDS STRONG CHAMPIONS HAND Coolmore and Bridlewood Farm=s Moonshine Memories John Gosden has already collected seven British Group 1s (Malibu Moon) looked well on her way to a divisional this year, and he could come away with a few more trophies championship after back-to-back Grade I wins last September, on British Champions Day. Click or tap here to go straight to TDN Europe. -

British Jump Pattern and Listed Races 2019/2020

BritishBritish JumpJump PatternPattern andand ListedListed RacesRaces 2019/20202019/2020 The Jump Pattern and Listed Race Book is an official publication of the British Horseracing Authority Limited. Registered Office: 75 High Holborn, London, WC1V 6LS. Registered Number 2813358 England. Telephone: 020 7152 0000 Fax: 020 7152 0001. Email: [email protected] PUBLISHED BY THE BRITISH HORSERACING AUTHORITY ©BRITISH HORSERACING AUTHORITY LTD., 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this material may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording or re-publication without the written permission of the British Horseracing Authority to whom such application for permission should be addressed. Such written permission must also be obtained if any part hereof is stored on a retrieval system of any nature. HANDICAPS AND OTHER RATING RELATED RACES HANDICAP RATING FOR QUALIFICATION Before making entries for Handicaps and other Rating Related races, reference must be made to the qualifying Rating Lists published on the Information area of the British Horseracing Authority Racing Administration Service Internet site each Tuesday. These ratings will apply for qualification purposes for races closing on the Tuesday of publication through to the following Monday. Amendments to these qualifying ratings will also be published, for information, on the Information area of the Racing Administration Internet site. HANDICAPS WITH SPLIT ENTRY STAKE FEES For those Handicap races which have a split entry stake fee dependent on the Handicap rating of the horse, i.e. £xx stake if the horse is rated aa or higher, or £yy stake if the horse is rated bb or lower with £zz extra if the horse is declared to run The relevant stake fee shall be determined by the Handicap rating used to calculate the weight for each horse entered in the race in question, and not by the published qualifying rating, if any. -

2015 GRAND NATIONAL SWEEPSTAKE KIT Crabbie’S Grand National Chase, Aintree, 4.15Pm, CH4 4M3f

2015 GRAND NATIONAL SWEEPSTAKE KIT Crabbie’s Grand National Chase, Aintree, 4.15pm, CH4 4m3f 1 LORD WINDERMERE 9 11-10 21 MONBEG DUDE 10 10-7 J H CULLOTY R MCNAMARA M SCUDAMORE L TREADWELL 2 MANY CLOUDS 8 11-9 22 CORRIN WOOD 8 10-7 O SHERWOOD L ASPELL D MCCAIN D J CASEY 3 UNIONISTE 7 11-6 23 THE RAINBOW HUNTER 11 10-7 P NICHOLLS N FEHILY K BAILEY D BASS 4 ROCKY CREEK 9 11-3 24 SAINT ARE 9 10-6 P NICHOLLS S TWISTON-DAVIES T GEORGE P BRENNAN 5 FIRST LIEUTENANT 10 11-3 25 ACROSS THE BAY 11 10-6 M F NORRIS MS N CARBERRY D MCCAIN H BROOKE 6 BALTHAZAR KING 11 11-2 26 TRANQUIL SEA 13 10-5 P HOBBS R JOHNSON W GREATREX G SHEEHAN 7 SHUTTHEFRONTDOOR 8 11-2 27 OSCAR TIME 14 10-5 J O’NEILL A P MCCOY R WALEY-COHEN MR S WALEY-COHEN 8 PINEAU DE RE 12 11-0 28 BOB FORD 8 10-4 DR R NEWLAND D JACOB R CURTIS P TOWNEND 9 BALLYCASEY 8 10-13 29 SUPER DUTY 9 10-4 W P MULLINS R WALSH I WILLIAMS W KENNEDY 10 SPRING HEELED 8 10-12 30 WYCK HILL 11 10-4 J H CULLOTY N SCHOLFIELD D BRIDGWATER T CANNON 11 REBEL REBELLION 10 10-12 31 GAS LINE BOY 9 10-4 P NICHOLLS R MAHON P HOBBS J BEST 12 DOLATULO 8 10-11 32 CHANCE DU ROY 11 10-4 W GREATREX D COSTELLO P HOBBS T O’BRIEN 13 MON PARRAIN 9 10-11 33 PORTRAIT KING 10 10-3 P NICHOLLS S BOWEN M PHELAN D CONDON 14 34 OWEGA STAR 8 10-3 NON-RUNNER P FAHEY R POWER 15 NIGHT IN MILAN 9 10-9 35 RIVER CHOICE 12 10-3 K REVELEY J REVELEY R CHOTARD D COTTIN 16 RUBI LIGHT 10 10-9 36 COURT BY SURPRISE 10 10-3 R A HENNESSY A E LYNCH E LAVELLE R MCLERNON 17 THE DRUIDS NEPHEW 8 10-9 37 ALVARADO 10 10-3 N MULHOLLAND A COLEMAN F O’BRIEN P MOLONEY 18 CAUSE OF CAUSES 7 10-9 38 SOLL 10 10-2 G ELLIOTT P CARBERRY D PIPE T SCUDAMORE 19 GODSMEJUDGE 9 10-8 39 ELY BROWN 10 10-2 A KING W HUTCHINSON C LONGSDON B HUGHES 20 AL CO 10 10-8 40 ROYALE KNIGHT 9 10-2 P BOWEN D O’REGAN DR R NEWLAND B POWELL 2015 GRAND NATIONAL SWEEPSTAKE KIT 1) Get your friends together and decide how much you want to stake (e.g. -

Smarterinsighttm

TM smarterinsight Grand National Tips 17th March, 2016 Confidential. Copyright © 2016. All rights reserved . 1 | P a g e 2016 Grand National Tips Spring got off to a great start with an early Easter and brighter evenings and it also means it’s time for QED’s Grand National tips! For those of you in a hurry, my tips are at the end of this article. Disclaimer - I have not enjoyed great Grand National success over the years, but that won't stop me from sharing my tips and tactics with you. But, before we get into the euphoria of all that, you would be disappointed if I did not throw in a few ‘risk warnings’: Risk warnings Tipping horses is not an activity regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Betting on a horse is a gamble not an investment. A bit like high tech stocks on P/E ratios of 200 plus in 2000. I have no qualifications or expertise in horse racing and my past performance is no indication of future performance (which is a good thing?). What goes up might come down and not get up again. Especially over Becher’s Brook. Only bet for fun and with an amount you would be happy to lose. If you want decent long term returns send your money to QED not Ladbrokes. Your relationship might be at risk if you don’t place your partner’s (or boss’!) winning bet. A word on Efficient Markets … In an efficient market the price contains all the known information. If new information arrives it can change the price. -

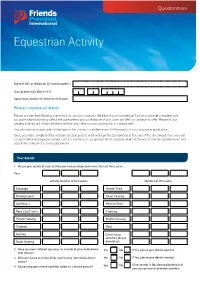

Equestrian Activity Questionnaire

Questionnaire Equestrian Activity Name in full (as shown on ID card/passport) Date of birth (DD/MM/YYYY) Application number or reference (if known) Please complete all details. Please answer the following questions fully and accurately to the best of your knowledge. Failure to provide complete and accurate information may affect the assessment and acceptance of any cover we offer or continue to offer. Please do not assume that we will obtain information from any other sources we may be in contact with. Any information you provide will be kept in the strictest confidence and will form part of your insurance application. Once you have completed the relevant section, please read and sign the Declaration at the end of this document. If you run out of space when writing your answers, please continue on a separate sheet of paper, make reference to it in the questionnaire and attach the extra sheets to this document. Your details 1 Please give details of each activity you have participated in over the last three years. Year Activity Number of Occasions Number of Occasions Dressage Hunter Trials Driving Events Team Chasing Gymkhana Point to Point Pony Club Events Eventing Private Hacking Hunter Chasing Showing Polo Hunting Other riding activities, please Show Jumping give details 2 Have you ever suffered any injury as a result of your involvement Yes No If Yes, please give details overleaf with horses? 3 Will your future activities differ significantly from those shown Yes No If Yes, please give details overleaf above? If the answer is No, please give details of 4 Do you engage in these activities solely as a leisure pursuit? Yes No your occupation involvement overleaf Data Protection This form collects your personal data. -

Welcome to Glenrothes Pony Club!

Welcome to Glenrothes Pony Club! Thank you for joining Glenrothes Branch of the Pony Club. We are a very friendly little Club, who pride ourselves on being welcoming, fun, supportive and encouraging. As a branch, we aim to provide fun with a competitive edge. We encourage our members to take part in all disciplines - we try to avoid specialisation too early, because we think it’s far more important that the children have fun, make friends and learn to look after their horses and ponies well. We run a varied programme of events over the year which although fun, encourages progression through the various equestrian disciplines. We welcome and encourage feedback as this is the only way that we can make things better for YOUR Club and its Members. If after reading this pack you still have questions, please feel free to contact Audrey, Diane, your Buddy or any Committee Member who will endeavour to help you. Audrey Nairns, District Commissioner Diane Hill, Assistant District Commissioner About this Pack: In this pack, we’ll try to explain: A bit about Glenrothes Branch Who we are What we do Where we go What to do and what to wear Where to find out more Who to contact and, finally, we’ll try to answer some of your questions Frequently Asked Questions About Glenrothes: Glenrothes Branch covers a very wide geographical area, from St Andrews to Kinross, Kirkcaldy to Tayport. We accept Members aged from 3 to 25! Currently we have about 35 members, the youngest being 4 and the oldest 22! The senior’s often help out at Rallies and Camp, and are encouraged to act as role models for the younger Members. -

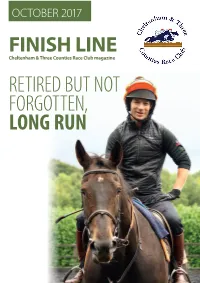

Retired but Not Forgotten, Long Run Welcome to the October Newsletter

OC TOBER 2017 FINISH LINE Cheltenham & Three Counties Race Club magazine RETIRED BUT NOT FORGOTTEN, LONG RUN WELCOME TO THE OCTOBER NEWSLETTER CONTENTS Have you bought your Cheltenham Annual ‘Events’. Next stable visit is to Gordon Elliott on Membership yet? Don’t forget the season Oct 18th and Dec 2nd. We also have visits to Olly starts on 27th/28th October and as a Murphy and Laura Hurley on the cards. member of CTCRC you get the £100 joining Editors Introduction 3 The Leading Jockey at Worcester presentation fee waived. Can I remind all members that Sarah-Jane Muirie guest column 4-5 will be held on the last day of the season we have a stand at this meeting and still which is Wednesday 25th October and is also McCoy's award winners 5-9 need volunteers to man it. If you can help the ‘Brush Hurdle Series Final Day’ as well as Overbury Stud visit 10-11 out for an hour please email David Bishop Halloween Raceday. Don’t forget CTCRC 2 for 1 Jo Collinson column 12-15 on [email protected] offer at Worcester. Please phone the day before Vet Section 16-17 I would like to take this opportunity to say a with membership number not on raceday. Dodge's new adventure 18-19 BIG ‘Thank You’ to Steve Ennis for all his hard Please remember we are also on social media. Neil Mulholland column 20-21 work on the newsletter and hope he enjoys his Facebook: www.facebook.com/ Nick Scholfield column 22 retirement from the monthly deadlines. -

Sports Quiz 2016

SPORTS QUIZ 2016 Q1 – 5 Multiple Choice - Easy for Starters! Q1) Adolf Dassler founded which sports company in 1948? a) Adidas b) Nike c) Mizuno Q2) From which seaport town does the Fastnet yachting race embark? a) Grimsby b) Cowes c) Portsmouth Q3) What is the first name of horse racing trainer Ted Walsh’s jockey son? a) Emerald b) Topaz c) Ruby Q4) Which golfing major title did Zach Johnson win in 2007? a) US Open b) Masters c) Olympics Q5) During the 2007 Cricket World Cup, South Africa’s Herschelle Gibbs hit a record number of runs in one over, how many? a) 28 b) 34 c) 36 Q6 – 20 2015 – What Do You Remember? Q6) Who won the Barclays Premier League Golden Boot (14/15)? Sergio Aguero Q7) Who won the FA Cup? Arsenal Q8) Who won the Europa Cup? Sevilla Q9) Who was the BBC Sports Personality of the Year? Andy Murray Q10) Which horse won the Cheltenham Gold Cup? Coneygree Q11) Who won the Open Golf? Zach Johnson Q12) Who won the Carling Cup? Chelsea Q13) Who won the Women’s Wimbledon title? Serena Williams Q14) Who won Cricket’s Twenty 20 Blast? Lancashire Q15) Who won Snooker’s World Championship? Stuart Bingham Q16) Who won the Six Nations Rugby Union? Ireland Q17) Who won Rugby League’s Super League Grand Final? Leeds Rhinos Q18) Which horse won the Grand National? Many Clouds Q19) Who won the Men’s Wimbledon title? Novak Djokovic Q20) Who won Football League Championship (14/15) Bournemouth Q21 – 25 Football Club Nicknames Q21) Addicks Charlton Q22) Cod Army Fleetwood Town Q23) Glovers Yeovil Town Q24) Saddlers Walsall Q25) Tigers Hull -

Magna Grecia, Calyx to Join Coolmore's Australian Team

Saturday, April 25, 2020 | Dedicated to the Australasian bloodstock industry - subscribe for free: Click here Magna Grecia, Calyx Read Tomorrow's Issue For: Saturday’s Stakes Reviews & Results to join Coolmore’s What's on Stakes races: Rosehill (NSW) - Hawkesbury Guineas (Gr 3, 1400m), Hawkesbury Gold Australian team Cup (Gr 3, 1500m), Hawkesbury Crown (Gr Sons of Invincible Spirit and Kingman set to join Everest winner 3, 1300m), Hawkesbury Gold Rush (Listed, Yes Yes Yes 1100m). Flemington (VIC) - VRC St Leger (Listed, 2800m), Anzac Day Stakes (Listed, 1400m). Morphettville (QLD) - Chairman’s Stakes (Gr 3, 2000m), Breeders’ Stakes (Gr 3, 1200m), City Of Adelaide Handicap (Listed, 1400m), H C Nitschke Stakes (Listed, 1400m). Ascot (WA) - Sheila Gwynne Classic (Listed, 1400m) Metropolitan meetings: Rosehill (NSW), Flemington (VIC), Sunshine Coast (QLD), Morphettville Parks (SA), Ascot (WA) Race meetings: Gosford (NSW), Bathurst (NSW), Moe (VIC), Dalby (QLD), Emerald (QLD), Kalgoorlie (WA), Pioneer Park (NT) Barrier trials/ Jump-outs: Armidale (NSW), Bathurst (NSW), Kempsey (NSW), Murwillumbah (NSW) International meetings: Tokyo (JPN), Kyoto (JPN), Fukushima (JPN), Taipa (MAC) International Group races: Fukushima (JPN) Magna Grecia COOLMORE - Fukushima Himba Stakes (Gr 3, 1800m) The trio will join a loaded cohort that includes BY ANDREW HAWKINS | @ANZ_NEWS the evergreen Fastnet Rock (Danehill), two oolmore Stud announced last Golden Slipper Stakes (Gr 1, 1200m) winners in night that European first season Vancouver (Medaglia d’Oro) and Pierro (Lonhro), sires Magna Grecia (Invincible dual hemisphere sensations So You Think (High Spirit) and Calyx (Kingman) will Chaparral) and Merchant Navy (Fastnet Rock) Cjoin The Everest (1200m) winner Yes Yes Yes and two American Triple Crown winners, (Rubick) as new additions to their Australian American Pharoah (Pioneerof The Nile) and roster for the 2020 breeding season.