Three Chords and the Truth Part I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Twenty Greatest Music Concerts I've Ever Seen

THE TWENTY GREATEST MUSIC CONCERTS I'VE EVER SEEN Whew, I'm done. Let me remind everyone how this worked. I would go through my Ipod in that weird Ipod alphabetical order and when I would come upon an artist that I have seen live, I would replay that concert in my head. (BTW, since this segment started I no longer even have an ipod. All my music is on my laptop and phone now.) The number you see at the end of the concert description is the number of times I have seen that artist live. If it was multiple times, I would do my best to describe the one concert that I considered to be their best. If no number appears, it means I only saw that artist once. Mind you, I have seen many artists live that I do not have a song by on my Ipod. That artist is not represented here. So although the final number of concerts I have seen came to 828 concerts (wow, 828!), the number is actually higher. And there are "bar" bands and artists (like LeCompt and Sam Butera, for example) where I have seen them perform hundreds of sets, but I counted those as "one," although I have seen Lecompt in "concert" also. Any show you see with the four stars (****) means they came damn close to being one of the Top Twenty, but they fell just short. So here's the Twenty. Enjoy and thanks so much for all of your input. And don't sue me if I have a date wrong here and there. -

L the Charlatans UK the Charlatans UK Vs. the Chemical Brothers

These titles will be released on the dates stated below at physical record stores in the US. The RSD website does NOT sell them. Key: E = Exclusive Release L = Limited Run / Regional Focus Release F = RSD First Release THESE RELEASES WILL BE AVAILABLE AUGUST 29TH ARTIST TITLE LABEL FORMAT QTY Sounds Like A Melody (Grant & Kelly E Alphaville Rhino Atlantic 12" Vinyl 3500 Remix by Blank & Jones x Gold & Lloyd) F America Heritage II: Demos Omnivore RecordingsLP 1700 E And Also The Trees And Also The Trees Terror Vision Records2 x LP 2000 E Archers of Loaf "Raleigh Days"/"Street Fighting Man" Merge Records 7" Vinyl 1200 L August Burns Red Bones Fearless 7" Vinyl 1000 F Buju Banton Trust & Steppa Roc Nation 10" Vinyl 2500 E Bastille All This Bad Blood Capitol 2 x LP 1500 E Black Keys Let's Rock (45 RPM Edition) Nonesuch 2 x LP 5000 They's A Person Of The World (featuring L Black Lips Fire Records 7" Vinyl 750 Kesha) F Black Crowes Lions eOne Music 2 x LP 3000 F Tommy Bolin Tommy Bolin Lives! Friday Music EP 1000 F Bone Thugs-N-Harmony Creepin' On Ah Come Up Ruthless RecordsLP 3000 E David Bowie ChangesNowBowie Parlophone LP E David Bowie ChangesNowBowie Parlophone CD E David Bowie I’m Only Dancing (The Soul Tour 74) Parlophone 2 x LP E David Bowie I’m Only Dancing (The Soul Tour 74) Parlophone CD E Marion Brown Porto Novo ORG Music LP 1500 F Nicole Bus Live in NYC Roc Nation LP 2500 E Canned Heat/John Lee Hooker Hooker 'N Heat Culture Factory2 x LP 2000 F Ron Carter Foursight: Stockholm IN+OUT Records2 x LP 650 F Ted Cassidy The Lurch Jackpot Records7" Vinyl 1000 The Charlatans UK vs. -

Ill Sleep When Im Dead: the Dirty Life and Times of Warren Zevon Free

FREE ILL SLEEP WHEN IM DEAD: THE DIRTY LIFE AND TIMES OF WARREN ZEVON PDF Crystal Zevon | 480 pages | 07 Jan 2009 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780060763497 | English | New York, United States Ill Sleep When Im Dead: The Dirty Life and Times of Warren Zevon by Crystal Zevon - PopMatters Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. When Warren Zevon died inhe left behind both a fanatical cult following and a rich catalog of dark, witty rock-n-roll classics that includes "Lawyers, Guns, and Money," "Excitable Boy," and the immortal "Werewolves of London. As Warren When Warren Zevon died inhe left behind both a fanatical cult following and a rich catalog of dark, witty rock-n-roll classics that includes "Lawyers, Guns, and Money," "Excitable Boy," and the immortal "Werewolves of London. As Warren once said, "I got to be Jim Morrison a lot longer than he did. Narrated by his former wife and longtime co-conspirator, Crystal Zevon, the book draws on over eighty interviews with the likes of Bruce Springsteen, Stephen King, Billy Bob Thornton, Jackson Browne, Bonnie Raitt, and countless others who came under his mischievous spell. The result is a raucous and moving tale of love and obsession, creative genius and epic bad behavior. Told in the words and images of the friends, lovers, and legends Ill Sleep When Im Dead: The Dirty Life and Times of Warren Zevon knew him best, I'll Sleep When I'm Dead captures Warren Zevon in all his turbulent glory. -

HIGH SOUTH a Change in the Wind with Impressive Three-Part Harmonies, a Dedication to Songwriting, and Unwavering Optimism

HIGH SOUTH A Change in the Wind With impressive three-part harmonies, a dedication to songwriting, and unwavering optimism, the Nashville-based band High South has developed a dedicated following across Europe, where they’ve been touring regularly there since 2015. Now they’re breaking into the American market with A Change in the Wind, a captivating project that draws comparisons to classic rock bands like the Eagles, Doobie Brothers, and Crosby, Stills and Nash. The group – composed of Jamey Garner, Kevin Campos, and Phoenix Mendoza – sums up it this way: “As vocalists we are always drawn to harmony. It’s such a naturally pleasing sound that we're absolutely hooked on -- and it was never more prevalent than the 1970s. Every kid learns from their environment and we were all fortunate to have parents that exposed us to the music of this era. In a sense, it’s in our soul.” With a desire to carry on that iconic ‘70s vibe, High South teamed with producer Josh Leo, known for his work with Glenn Frey, Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, Jimmy Buffett, and Kim Carnes, as well as No. 1 hits for country artists Love & Theft and Emerson Drive. Other collaborators on A Change in the Wind include engineer Niko Bolas (Neil Young, Don Henley, Warren Zevon), guitarist Jack Pearson (Allman Brothers Band), keyboard player Tony Harrell (Flying Burrito Brothers), drummer Nir Z (Genesis), and singer Raul Malo (The Mavericks). Although the band released several singles internationally through Universal Germany, A Change in the Wind is their first release with distribution in America. -

Rock, Blues, R&B

When your club or special event is ready to party, call the party band that brings a professional look, sound and attitude. Where’s Eddie will have your guest participating in the celebration of great music, played well with quality sound and lights. Meet the Band: What we’re currently playing: Country & Southern Rock Beer In Mexico Kenny Chesney Beer Money Kip Moore Drink In My Hand Eric Church Every Time I Roll The Dice Delbert McClinton Gimme Three Steps Lynyrd Skynyrd Honey Bee Blake Shelton Honky Tonk Woman Rolling Stones How Country Feels Randy Houser Keep Your Hands to Yourself Georgia Satellites Lights Come On Jason Aldean Save A Horse Big & Rich Sweet Home Alabama Lynyrd Skynyrd Tattoos On This Town Jason Aldean T-Shirt Thomas Rhett Ticks Brad Paisley You Look Good In My Shirt Keith Urban You Look Like I Need A Drink Justin Moore Rock, Blues, R&B Addicted To Love Robt. Palmer Just What I Needed Cars Aint No Sunshine Bill Withers Learn To Fly Foo Fighters Lonely Boy Black Keys All Summer Long Kid Rock American Girl Tom Petty Overkill Men at Work/Lazlo Bane Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jet Pink Houses Mellencamp Basket Case Green Day Rock & Roll All Night Kiss Birthday Beatles Start It Up Robben Ford Brown Sugar Stones Superstition Stevie Wonder/SRV Crossfire Stevie Ray Vaughn The Boys Of Summer Eagles/Ataris Feelin' Alright Traffic/Joe Cocker The Middle Jimmy Eat World Fly Away Lenny Kravitz Tumblin Dice Rolling Stones Hard to Handle Otis/Black Crowes Use Me Bill Withers Harder to Breathe Maroon 5 Werewolves of London Warren Zevon Hey Jealousy Gin Blossoms Wild Nights Van /Mellencamp How You Like Me Now The Heavy You May Be Right Billy Joel I Don't Wanna Be Gavin DeGraw You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC I'll Be Your Man The Black Keys Use Somebody Kings of Leon Jealous Again Black Crowes As you can see, there’s a wide variety of music available for your event. -

Classic Rock/ Metal/ Blues

CLASSIC ROCK/ METAL/ BLUES Caught Up In You- .38 Special Girls Got Rhythm- AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long- AC/DC Angel- Aerosmith Rag Doll- Aerosmith Walk This Way- Aerosmith What It Takes- Aerosmith Blue Sky- The Allman Brothers Band Melissa- The Allman Brothers Band Midnight Rider- The Allman Brothers Band One Way Out- The Allman Brothers Band Ramblin’ Man- The Allman Brothers Band Seven Turns- The Allman Brothers Band Soulshine- The Allman Brothers Band House Of The Rising Sun- The Animals Takin’ Care Of Business- Bachman-Turner Overdive You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet- Bachman-Turner Overdrive Feel Like Makin’ Love- Bad Company Shooting Star- Bad Company Up On Cripple Creek- The Band The Weight- The Band All My Loving- The Beatles All You Need Is Love- The Beatles Blackbird- The Beatles Eight Days A Week- The Beatles A Hard Day’s Night- The Beatles Hello, Goodbye- The Beatles Here Comes The Sun- The Beatles Hey Jude- The Beatles In My Life- The Beatles I Will- Beatles Let It Be- The Beatles Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)- The Beatles Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da- The Beatles Oh! Darling- The Beatles Rocky Raccoon- The Beatles She Loves You- The Beatles Something- The Beatles CLASSIC ROCK/ METAL/ BLUES Ticket To Ride- The Beatles Tomorrow Never Knows- The Beatles We Can Work It Out- The Beatles When I’m Sixty-Four- The Beatles While My Guitar Gently Weeps- The Beatles With A Little Help From My Friends- The Beatles You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away- The Beatles Johnny B. -

Led Zeppelin R.E.M. Queen Feist the Cure Coldplay the Beatles The

Jay-Z and Linkin Park System of a Down Guano Apes Godsmack 30 Seconds to Mars My Chemical Romance From First to Last Disturbed Chevelle Ra Fall Out Boy Three Days Grace Sick Puppies Clawfinger 10 Years Seether Breaking Benjamin Hoobastank Lostprophets Funeral for a Friend Staind Trapt Clutch Papa Roach Sevendust Eddie Vedder Limp Bizkit Primus Gavin Rossdale Chris Cornell Soundgarden Blind Melon Linkin Park P.O.D. Thousand Foot Krutch The Afters Casting Crowns The Offspring Serj Tankian Steven Curtis Chapman Michael W. Smith Rage Against the Machine Evanescence Deftones Hawk Nelson Rebecca St. James Faith No More Skunk Anansie In Flames As I Lay Dying Bullet for My Valentine Incubus The Mars Volta Theory of a Deadman Hypocrisy Mr. Bungle The Dillinger Escape Plan Meshuggah Dark Tranquillity Opeth Red Hot Chili Peppers Ohio Players Beastie Boys Cypress Hill Dr. Dre The Haunted Bad Brains Dead Kennedys The Exploited Eminem Pearl Jam Minor Threat Snoop Dogg Makaveli Ja Rule Tool Porcupine Tree Riverside Satyricon Ulver Burzum Darkthrone Monty Python Foo Fighters Tenacious D Flight of the Conchords Amon Amarth Audioslave Raffi Dimmu Borgir Immortal Nickelback Puddle of Mudd Bloodhound Gang Emperor Gamma Ray Demons & Wizards Apocalyptica Velvet Revolver Manowar Slayer Megadeth Avantasia Metallica Paradise Lost Dream Theater Temple of the Dog Nightwish Cradle of Filth Edguy Ayreon Trans-Siberian Orchestra After Forever Edenbridge The Cramps Napalm Death Epica Kamelot Firewind At Vance Misfits Within Temptation The Gathering Danzig Sepultura Kreator -

THE ROCKIN' RAVERS SONG LIST C/O Jerry Bruno Productions

THE ROCKIN' RAVERS SONG LIST C/O Jerry Bruno Productions MUSIC FROM 2000 TO PRESENT Here It Goes Again--OK GO Vertigo--U2 Are You Gonna Be My Girl—Jet Dirty Little Secret--All-American Rejects Heaven—Los Lonely Boys Can't Get Enough Of You Baby--Smash Mouth Times Like These—Foo Fighters The First Cut Is The Deepest—Sheryl Crow The Middle—Jimmy Eat World I’m A Believer—Smash Mouth Have Love Will Travel--The Black Keys Kryptonite--Three Doors Down Absolutely (Story of a Girl)—Ninedays MUSIC FROM 1990s I'll Be -- Edwin McCain Slide – Goo Goo Dolls The Way – Fastball All The Small Things – Blink 182 Mr. Jones – Counting Crows All For You – Sister Hazel Little Miss Can’t Be Wrong – Spin Doctors Good – Better Than Ezra Found Out About You – Gin Blossoms Again Tonight – John Cougar Mellencamp Wicked Game – Chris Isaak Have I Told You Lately That I Love You – Van Morrison Lay-heed – James Save Tonight – Eagle-eye Cherry There She Goes – The La’s/Sixpence None The Richer Breakfast At Tiffany’s – Deep Blue Something Wild Night – John Cougar Mellencamp/Van Morrison All Shook Up – Paul McCartney/Elvis Presley MUSIC FROM 1980s Jessie's Girl -- Rick Springfield Summer of '69 -- Bryan Adams What I Like About You -- Romantics I Got You -- Split Enz I Won't Back Down -- Tom Petty Sweet Child O' Mine -- Guns n' Roses Authority Song – John Cougar Mellencamp Start Me Up – Rolling Stones 500 Miles – Proclaimers Old Time Rock And Roll – Bob Seger Melt With You – Modern English The One I Love – R.E.M. -

Pink Floyd - Dark Side of the Moon Speak to Me Breathe on the Run Time the Great Gig in the Sky Money Us and Them Any Colour You Like Brain Damage Eclipse

Pink Floyd - Dark Side of the Moon Speak to Me Breathe On the Run Time The Great Gig in the Sky Money Us and Them Any Colour You Like Brain Damage Eclipse Pink Floyd – The Wall In the Flesh The Thin Ice Another Brick in the Wall (Part 1) The Happiest Days of our Lives Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2) Mother Goodbye Blue Sky Empty Spaces Young Lust Another Brick in the Wall (Part 3) Hey You Comfortably Numb Stop The Trial Run Like Hell Laser Queen Bicycle Race Don't Stop Me Now Another One Bites The Dust I Want To Break Free Under Pressure Killer Queen Bohemian Rhapsody Radio Gaga Princes Of The Universe The Show Must Go On 1 Laser Rush 2112 I. Overture II. The Temples of Syrinx III. Discovery IV. Presentation V. Oracle: The Dream VI. Soliloquy VII. Grand Finale A Passage to Bangkok The Twilight Zone Lessons Tears Something for Nothing Laser Radiohead Airbag The Bends You – DG High and Dry Packt like Sardine in a Crushd Tin Box Pyramid song Karma Police The National Anthem Paranoid Android Idioteque Laser Genesis Turn It On Again Invisible Touch Sledgehammer Tonight, Tonight, Tonight Land Of Confusion Mama Sussudio Follow You, Follow Me In The Air Tonight Abacab 2 Laser Zeppelin Song Remains the Same Over the Hills, and Far Away Good Times, Bad Times Immigrant Song No Quarter Black Dog Livin’, Lovin’ Maid Kashmir Stairway to Heaven Whole Lotta Love Rock - n - Roll Laser Green Day Welcome to Paradise She Longview Good Riddance Brainstew Jaded Minority Holiday BLVD of Broken Dreams American Idiot Laser U2 Where the Streets Have No Name I Will Follow Beautiful Day Sunday, Bloody Sunday October The Fly Mysterious Ways Pride (In the Name of Love) Zoo Station With or Without You Desire New Year’s Day 3 Laser Metallica For Whom the Bell Tolls Ain’t My Bitch One Fuel Nothing Else Matters Master of Puppets Unforgiven II Sad But True Enter Sandman Laser Beatles Magical Mystery Tour I Wanna Hold Your Hand Twist and Shout A Hard Day’s Night Nowhere Man Help! Yesterday Octopus’ Garden Revolution Sgt. -

Script-Howlers

BLACK SCREEN. In white the words appear; "IF YOU HEAR HIM HOWLIN' 'ROUND YOUR KITCHEN DOOR YOU BETTER NOT LET HIM IN" Werewolves of London W. Zevon This is replaced with; "THE FOLLOWING EVENTS ARE BASED ON A TRUE STORY..." CLAWS slash through the screen. FADE IN: EXT. COUNTRYSIDE-NIGHT. The moon is full and hangs like a cold, harsh white-blue rock on the black velvet that is the night sky. There is no cloud cover. GAZ, over-weight, bearded, in his early 30s. He is wearing a quiver filled with arrows and is carrying a bow. He is a lifelong failing criminal, and part-time poacher, and; DAZ, skinny, early 30s, has spent his whole life following Gaz to absolutely nowhere. He is the type of person who thinks being on The Jeremy Kyle Show is something to aspire to. They are stood on the edge of woodland, and about to cross the treeline. They are dressed quite warmly, although both are in trainers and tracksuit bottoms, proving that they don't really know what they're doing. DAZ Jesus, can we hurry this up? It's freezing. GAZ I know it's freezing, you girl. But I don't want to cock this up. DAZ What do you want to cock up? GAZ I'd say your mam, but there's a queue. 2. DAZ (quietly) Mam? GAZ Now have you got the bags? DAZ No, I just stand like this because it's cold. GAZ I'm going to bloody swing for you in a minute. -

Thanks for Coming out Tonight. Look Over the List and Let Me Know What You’D Like to Hear

Thanks for coming out tonight. Look over the list and let me know what you’d like to hear. Above all else . Have a good time! I also write a lot of music. My songs are listed first on the list and are in red. CD’s are $10. Enjoy. --- Domenick Domenick Swentosky Times they are A-Changin’ --(My Original Songs)-- All Along the Watchtower Dire Staits The Great Divide Shelter from the Storm Romeo and Juliet Liar Bob Marley Dispatch Walking Bob Dylan Redemption Song The General Goodbye Goldie Bobby McFerrin Don Maclean Afterlife Don’t Worry, Be Happy American Pie Grandfather Bob Seger The Doors Louisiana Poor Turn the Page Love Me Two Times Never Leave Against the Wind The Eagles Here Bon Jovi Take It Easy Haunted Dead or Alive Elton John Downtown Bowling For Soup Daniel Ever Be Come Back to Texas Tiny Dancer Saturday Brian Adams Rocketman Joyride Summer of ‘69 Levon Runnin’ Free Bright Eyes Elvis Presley Good Enough First Day of My Life Return to Sender Discover Bruce Hornsby Eric Clapton Six Strings The Way It Is San Francisco Bay Blues Come On Around Buffalo Springfield Layla The Last Time For What It’s Worth Everlast Storm Inside the Calm Bush What It’s Like Hideaway Machinehead Fall Out Boy The Postage Glycerine Sugar We’re Going Down The Simple Life Cat Stevens Five For Fighting Aerosmith Wild World America Town FINE First Cut is the Deepest Fleetwood Mac Alan Jackson CCR Landslide 5:00 Somewhere Have You Ever Seen the Rain Foo Fighters Alien Ant Farm Bad Moon Rising Learn To Fly Smooth Criminal The Clarks Everlong Allman Brothers Born -

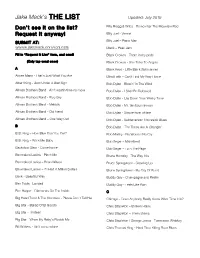

Jake Mack's the LIST

Jake Mack’s THE LIST Updated: July 2019 Don’t see it on the list? Billy Bragg & Wilco - Remember The Mountain Bed Request it anyway! Billy Joel - Vienna SUBMIT AT: Billy Joel – Piano Man wwww.jakemack.com/requests Black – Pearl Jam Fill in “Request It Live” form, and send! Black Crowes - Thorn in my pride (Only tap send once) Black Crowes - She Talks To Angels A Black Keys - Little Black Submarines Aimee Mann - That’s Just What You Are Blind Faith – Can’t Find My Way Home Albert King - Born Under A Bad Sign Bob Dylan - Blowin’ in The Wind Allman Brothers Band - Ain’t wastin time no more Bob Dylan - I Shall Be Released Allman Brothers Band - Blue Sky Bob Dylan - Lay Down Your Weary Tune Allman Brothers Band - Melissa Bob Dylan - Mr. tambourine man Allman Brothers Band - Old friend Bob Dylan - Simple twist of fate Allman Brothers Band – One Way Out Bob Dylan - Subterranean Homesick Blues B Bob Dylan – The Times Are A-Changin’ B.B. King – How Blue Can You Get? Bob Marley - No Woman No Cry B.B. King – Rock Me Baby Bob Seger – Mainstreet Backdoor Slam - Come home Bob Seger – Turn The Page Barenaked Ladies - Pinch Me Bruce Hornsby - The Way It Is Barenaked Ladies – Brian Wilson Bruce Springsteen - Growing Up Barenaked Ladies – If I Had A Million Dollars Bruce Springsteen - My City Of Ruins Beck - Beautiful Way Buddy Guy - Champagne and Reefer Ben Folds - Landed Buddy Guy - Feels Like Rain Ben Harper - Diamonds On The Inside C Big Head Todd & The Monsters - Please Don’t Tell Her Chicago - Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is? Big Star - Ballad