The East Anglian Foldcourse: Some Queries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baptism Data Available

Suffolk Baptisms - July 2014 Data Available Baptism Register Deanery or Grouping From To Acton, All Saints Sudbury 1754 1900 Akenham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1903 Aldeburgh, St Peter & St Paul Orford 1813 1904 Alderton, St Andrew Wilford 1754 1902 Aldham, St Mary Sudbury 1754 1902 Aldringham cum Thorpe, St Andrew Dunwich 1813 1900 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul Sudbury 1754 1901 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul (BTs) Sudbury 1780 1792 Ampton, St Peter Thedwastre 1754 1903 Ashbocking, All Saints Bosmere 1754 1900 Ashby, St Mary Lothingland 1813 1900 Ashfield cum Thorpe, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Great Ashfield, All Saints Blackbourn 1765 1901 Aspall, St Mary of Grace Hartismere 1754 1900 Assington, St Edmund Sudbury 1754 1900 Athelington, St Peter Hoxne 1754 1904 Bacton, St Mary Hartismere 1754 1901 Badingham, St John the Baptist Hoxne 1813 1900 Badley, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1902 Badwell Ash, St Mary Blackbourn 1754 1900 Bardwell, St Peter & St Paul Blackbourn 1754 1901 Barham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Barking, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1900 Barnardiston, All Saints Clare 1754 1899 Barnham, St Gregory Blackbourn 1754 1812 Barningham, St Andrew Blackbourn 1754 1901 Barrow, All Saints Thingoe 1754 1900 Barsham, Holy Trinity Wangford 1813 1900 Great Barton, Holy Innocents Thedwastre 1754 1901 Barton Mills, St Mary Fordham 1754 1812 Battisford, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1899 Bawdsey, St Mary the Virgin Wilford 1754 1902 Baylham, St Peter Bosmere 1754 1900 09 July 2014 Copyright © Suffolk Family History Society 2014 Page 1 of 12 Baptism Register Deanery or Grouping -

Role Description LVNB Team Vicar 50% Fte 2019

Role description signed off by: Archdeacon of Sudbury Date: April 2019 To be reviewed 6 months after commencement of the appointment, and at each Ministerial Development Review, alongside the setting of objectives. 1 Details of post Role title Team Vicar 50% fte, held in plurality with Priest in Charge 50% fte Barrow Benefice Name of benefices Lark Valley & North Bury Team (LVNB) Deanery Thingoe Archdeaconry Sudbury Initial point of contact on terms of Archdeacon of Sudbury service 2 Role purpose General To share with the Bishop and the Team Rector both in the cure of souls and in responsibility, under God, for growing the Kingdom. To ensure that the church communities in the benefice flourish and engage positively with ‘Growing in God’ and the Diocesan Vision and Strategy. To work having regard to the calling and responsibilities of the clergy as described in the Canons, the Ordinal, the Code of Professional Conduct for the Clergy and other relevant legislation. To collaborate within the deanery both in current mission and ministry and, through the deanery plan, in such reshaping of ministry as resources and opportunities may require. To attend Deanery Chapter and Deanery Synod and to play a full part in the wider life of the deanery. To work with the ordained and lay colleagues as set out in their individual role descriptions and work agreements, and to ensure that, where relevant, they have working agreements which are reviewed. This involves discerning and developing the gifts and ministries of all members of the congregations. To work with the PCCs towards the development of the local church as described in the benefice profile, and to review those needs with them. -

WSC Planning Applications 51/19

LIST 51 20 December 2019 Applications Registered between 16.12.2019 – 20.12.2019 PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED The following applications for Planning Permission, Listed Building, Conservation Area and Advertisement Consent and relating to Tree Preservation Orders and Trees in Conservation Areas have been made to this Council. A copy of the applications and plans accompanying them may be inspected on our website www.westsuffolk.gov.uk. Representations should be made in writing, quoting the application number and emailed to [email protected] to arrive not later than 21 days from the date of this list. Note: Representations on Brownfield Permission in Principle applications and/or associated Technical Details Consent applications must arrive not later than 14 days from the date of this list. Application No. Proposal Location DC/19/2449/EIASCR EIA Screening Opinion under Regulation 6 Proposed Development VALID DATE: (1) of the Environmental Impact Assessment At 18.12.2019 Regulations 2017 on the matter of whether St Genevieve Lakes or not the proposed development is Road From Bury Road EXPIRY DATE: considered that there are likely significant To B1106 08.01.2020 environmental impacts for which an Timworth Environmental Statement would be required Suffolk WARD: Pakenham & - 65no. holiday lodges Troston APPLICANT: Mr Ian Brooker PARISH: Ampton, Little GRID REF: Livermere & Timworth 585161 269093 CASE OFFICER: Penny Mills DC/19/2428/PIP Permission in Principal - 2-5no. dwellings Land Rear Of VALID DATE: Barrow Road 12.12.2019 -

Bury St Edmunds May 2018

May 2018 BURY ST EDMUNDS RESPOND INSPECTOR MATT DEE Police in Bury St Edmunds are currently investigating a series of Exposure offences that have taken place in the area of Moreton Hall. Offences have occurred on the 29th March, 22nd April, 3rd May and 6th May in the late afternoon. The offender is sometimes using a black and white bike and is described as either mixed race or tanned skinned male, aged late 20's to early 30's and short dark brown hair. Any witnesses or anyone with information are urged to come forward. MAKING YOUR COMMUNITY SAFER The SNT have attended a number of initiatives over the past month giving crime prevention advice and reassurance at different venues. PCSO Pooley attended a Fraud awareness day at Barclays bank, offering advice on keeping your bank account and personal finances safe. PCSO Howell attended Beetons Lodge, offering advice on personal safety and security. PCSO Chivers attended the first 'Meet up Monday' event at The Boosch Bar, a new initiative set up to lend a friendly ear to anyone FUTURE EVENTS vulnerable, lonely or even new to the area. The future events that your SNT are involved in, and will give you an opportunity to chat to them to raise your concerns are: PREVENTING, REDUCING AND SOLVING CRIME AND ASB 9th May - Great Whelnetham Parish PC Fox has investigated a series of three theft of peddle cycles meeting that were left insecure outside one of our town Upper schools. 10th May - Fornahm St Martin Parish Having reviewed the CCTV, the suspects were identified and meeting 13th May - South Suffolk Show offenders have all been caught. -

Bury St Edmunds

October 2017 BURY ST EDMUNDS RESPOND INSPECTOR MATT DEE On 29th September 2017 Bury St Edmunds Police responded to a large Fire at Cylce King, Bury St Edmunds. We worked with our colleagues from the fire service to evacuate the area, close the roads and secure the arrests of two males, on suspicion of Arson. In the aftermath of the fire we worked with our partners from the fire service and St Edmundsbury Borough Council to secure evidence, make the area safe, offering support to local businesses affected by the fire and to re-open the road as soon as possible to cause minimum disruption to the local community. MAKING YOUR COMMUNITY SAFER Bury SNT executed a drugs warrant in Rougham, after receiving and developing some community intelligence. 18 Cannabis Plants and growing equipment were seized, and a male was arrested for Cultivation of Cannabis. Bury SNT and Emergency Service Cadets assisted with the St Nicholas Hospice charity 'Girls Night Out', where over 2,500 ladies took to the FUTURE EVENTS street of the town in a sponsored walk, providing support and The future events that your SNT are reassurance to all involved. involved in, and will give you an opportunity to chat to them to raise your concerns are PREVENTING, REDUCING AND SOLVING CRIME AND ASB 9th October - PC Ellis will be at Lackford Bury SNT have been working in partnership with Havebury Housing Association to Parish Council meeting 7.30 pm, Lackford combat anti-social behaviour in Greene Road, BSE that has had a detrimental effect Church to the quality of lives of the local residents. -

Schedule of Highways Maintainable at Public Expense Within West Suffolk District

Schedule of Highways Maintainable at Public Expense within West Suffolk District Hint: To find a parish or street use Ctrl F The information in this “List of Streets” was derived from Suffolk County Council’s digital Local Street Gazetteer. While considerable care is taken to ensure the accuracy of the Street Gazetteer, Suffolk County Council cannot accept any responsibility for errors, omissions, or positional accuracy. There are no warranties, expressed or implied, including the warranty of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose, accompanying this product. However, notification of any errors will be appreciated. Street Part public location Length Km NSG Ref Route No. Ampton Carriageway Folly Lane 1.55 37403388 A134 Ingham Road 0.82 37403542 C650 New Road 2.17 37400982 C650, U6307 Public footpath Ampton Footpath 001 0.60 37490130 Y108/001/0 Bardwell Page 1 of 148 01/03/2021 Street Part public location Length Km NSG Ref Route No. Carriageway Bowbeck 2.06 37403082 C643 Church Road 0.31 37400567 U6429 Daveys Lane 0.74 37400639 U6439 Ixworth Road 0.84 37403548 C642 Ixworth Thorpe Road 1.04 37403552 U6428 Knox Lane 0.61 37400871 U6441 Lammas Close 0.18 37400877 U6430 Low Street 0.81 37400911 C642 Quaker Lane 0.65 37401072 C642 Road From A1088 To B1111 0.72 37401684 C643 Road From C642 To C643 0.86 37401745 U6424 Road From C644 And C642 To A1088 2.29 37401749 C642 School Lane 0.38 37401118 U6428 Spring Road 1.40 37401160 C642 Stanton Road 0.63 37401182 U6432 The Croft 0.42 37401222 U6430 The Green 0.34 37403966 U6439 Up Street -

MASTERPLAN December 2017

MASTERPLAN December 2017 01 INTRODUCTION 1.1 ABOUT THIS DOCUMENT Thank you for taking the time to consider the new masterplan proposals for St. Genevieve Lakes. St. Genevieve Lakes is the new name for the site at Park Farm, Ingham. This masterplan for St Genevieve Lakes builds on Policy RV6 and it’s adopted concept statement. This masterplan has been prepared by Corylus Planning and Environmental Ltd to promote high standards of design for the land identified by Policy RV6 of the Rural Vision 2031 Local Plan Document. A ‘Masterplan’ displays more detail than the preceding concept statement and provides a basis for later planning applications. Whilst the details are indicative, the document seeks to lay out the type of opportunities and uses that would allow the site to provide an alternative destination that could absorb the pressures of visitors to the area and mitigate potential effects on the Breckland Special Protection Area (SPA) of tourism. 1.2 TOURISM AND LEISURE AT ST GENEVIEVE LAKES “The restoration of the land has brought forward the opportunity for the creation of recreational, leisure and tourism facilities serving both the locality and the wider area which will bring both economic and community benefits to the area.” - Quoted Para 15.16 of St Edmundsbury Rural Vision 2031 3 02 POLICY CONTEXT AND THE CONCEPT STATEMENT 2.1 POLICY OVERVIEW The masterplan seeks to show the development • Policy DM2 & DM3 within the context of current and emerging national and local planning policies and local • Concept Statements environmental and infrastructure constraints. • any relevant design guidance Whilst Policy RV6 is a primary guide, proposals • any development briefs approved by the for development of sites subject to Masterplans Local Planning Authority require consideration against a range of policy documents, including: • any adopted supplementary planning documents. -

84 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

84 bus time schedule & line map 84 Thetford - Barnham - Ingham - Bury St Edmunds View In Website Mode The 84 bus line (Thetford - Barnham - Ingham - Bury St Edmunds) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bury St Edmunds: 6:30 AM - 4:45 PM (2) Thetford: 7:15 AM - 6:15 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 84 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 84 bus arriving. Direction: Bury St Edmunds 84 bus Time Schedule 28 stops Bury St Edmunds Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 6:30 AM - 4:45 PM Bus Interchange, Thetford 15 Water Lane, Thetford Tuesday 6:30 AM - 4:45 PM St Marys Church, Thetford Wednesday 6:30 AM - 4:45 PM 39 Bury Road, Thetford Thursday 6:30 AM - 4:45 PM Queensway, Thetford Friday 6:30 AM - 4:45 PM 140 Bury Road, Thetford Saturday 7:30 AM - 4:45 PM Bracken Road, Thetford Raf Camp, Barnham Mill Lane, Barnham 84 bus Info Direction: Bury St Edmunds School, Barnham Stops: 28 Trip Duration: 32 min Rymer Farm, Rymer Point Line Summary: Bus Interchange, Thetford, St Marys Church, Thetford, Queensway, Thetford, Bracken Sevenhills Lane, Seven Hills Road, Thetford, Raf Camp, Barnham, Mill Lane, Barnham, School, Barnham, Rymer Farm, Rymer The Cadogan, Ingham Point, Sevenhills Lane, Seven Hills, The Cadogan, Ingham, St Bartholomew's Church, Ingham, Timworth Farm, Timworth, Oak Close, Fornham St St Bartholomew's Church, Ingham Genevieve, Village Sign, Fornham St Martin, The Woolpack, Fornham St Martin, Barton Hill, Fornham Timworth Farm, Timworth St Martin, Tollgate Lane, Bury St Edmunds, Thingoe Bury Road, Timworth Civil Parish Hill, Bury St Edmunds, Fornham Road, Bury St Edmunds, Railway Station, Bury St Edmunds, Bus Oak Close, Fornham St Genevieve Station, Bury St Edmunds, Arc Shopping Centre, Bury Gleneagles Close, Fornham St. -

WSC Planning Decisions 09/20

PLANNING AND REGULATORY SERVICES DECISIONS WEEK ENDING 28/02/2020 PLEASE NOTE THE DECISIONS LIST RUN FROM MONDAY TO FRIDAY EACH WEEK DC/19/2449/EIASCR EIA Screening Opinion under Regulation 6 Proposed Development At DECISION: (1) of the Environmental Impact St Genevieve Lakes EIA Not Required Assessment Regulations 2017 on the Road From Bury Road To DECISION TYPE: matter of whether or not the proposed B1106 Delegated development is considered that there are Timworth ISSUED DATED: likely significant environmental impacts for Suffolk 27 Feb 2020 which an Environmental Statement would WARD: Pakenham & be required - 65no. holiday lodges Troston PARISH: Ampton, Little APPLICANT: Mr Ian Brooker Livermere & Timworth DC/19/2414/HH Householder Planning Application - (i) 3 St Martins Meadow DECISION: Single storey side and rear extensions Barnham Approve Application IP24 2NX DECISION TYPE: APPLICANT: Mr & Mrs J. Hemingfield Delegated ISSUED DATED: AGENT: Sturdivant Design Consultants Ltd 27 Feb 2020 WARD: Bardwell PARISH: Barnham DC/18/1551/OUT Outline Planning Application (all matters Land Adjacent North Court DECISION: reserved) - Woodland Retirement Village Brandon Road Refuse Application comprising of (i) 30no. dwellings and (ii) Brandon DECISION TYPE: community centre with leisure and health Suffolk Delegation Panel facilities ISSUED DATED: 28 Feb 2020 APPLICANT: TUFARNN LLAP, Farrukh & WARD: Brandon West Tuba Bajwa PARISH: Brandon AGENT: Abby Gretton - Clayland Architects Planning and Regulatory Services, West Suffolk Council, West Suffolk -

Schedule of Highways Maintainable at Public Expense Within West Suffolk District

Schedule of Highways Maintainable at Public Expense within West Suffolk District Hint: To find a parish or street use Ctrl F The information in this “List of Streets” was derived from Suffolk County Council’s digital Local Street Gazetteer. While considerable care is taken to ensure the accuracy of the Street Gazetteer, Suffolk County Council cannot accept any responsibility for errors, omissions, or positional accuracy. There are no warranties, expressed or implied, including the warranty of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose, accompanying this product. However, notification of any errors will be appreciated. Street Part public location Length Km NSG Ref Route No. Ampton Carriageway Folly Lane 1.55 37403388 A134 Ingham Road 0.82 37403542 C650 New Road 2.17 37400982 C650, U6307 Public footpath Ampton Footpath 001 0.60 37490130 Y108/001/0 Bardwell Page 1 of 148 01/04/2021 Street Part public location Length Km NSG Ref Route No. Carriageway Bowbeck 2.06 37403082 C643 Church Road 0.31 37400567 U6429 Daveys Lane 0.74 37400639 U6439 Ixworth Road 0.84 37403548 C642 Ixworth Thorpe Road 1.04 37403552 U6428 Knox Lane 0.61 37400871 U6441 Lammas Close 0.18 37400877 U6430 Low Street 0.81 37400911 C642 Quaker Lane 0.65 37401072 C642 Road From A1088 To B1111 0.72 37401684 C643 Road From C642 To C643 0.86 37401745 U6424 Road From C644 And C642 To A1088 2.29 37401749 C642 School Lane 0.38 37401118 U6428 Spring Road 1.40 37401160 C642 Stanton Road 0.63 37401182 U6432 The Croft 0.42 37401222 U6430 The Green 0.34 37403966 U6439 Up Street -

Polling Districts and Places Where No Changes Are Proposed

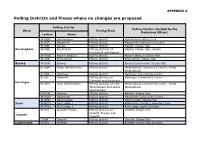

APPENDIX 2 Polling Districts and Places where no changes are proposed Polling District Polling Station (decided by the Ward Polling Place Returning Officer) Letters Name W-BGM Barningham Polling district Barningham Village Hall W-HEP Hepworth Polling district Hepworth Community Pavilion W-HOP Hopton Polling district Hopton Village Hall Barningham W-KNE Knettishall Polling districts of Hopton Village Hall, Hopton Knettishall and Hopton W-MWE Market Weston Polling district Market Weston Village Hall W-THE Thelnetham Polling district Thelnetham Village Hall Exning W-EXN Exning Polling district Exning Community Church Hall B-GWH Great Whelnetham Polling district Whelnetham Community Centre, Great Whelnetham B-HOR Horringer Polling district Horringer Community Centre B-ICK Ickworth Polling districts of Horringer Community Centre Ickworth and Horringer Horringer B-LWH Little Whelnetham Polling districts of Little Whelnetham Community Centre, Great Whelnetham and Great Whelnetham Whelnetham B-NOW Nowton Polling district Nowton Village Hall W-HAW Hawstead Polling district Hawstead Community Centre W-HER Herringswell Polling district Herringswell Village Hall Iceni W-REL1 Red Lodge 1 Polling district Millennium Centre, Lavender Close W-REL2 Red Lodge 2 Polling district Red Lodge Sports Pavilion W-IXT Ixworth Thorpe Polling districts of Ixworth Village Hall Ixworth Thorpe and Ixworth Ixworth I-IXW Ixworth Polling district Ixworth Village Hall Lakenheath W-ELV Elveden Polling district Elveden Village Hall, Elveden APPENDIX 2 Polling District Polling -

The Reduced Population and Wealth of Early Fifteenth

THE REDUCED POPULATION AND WEALTH OF EARLY FIFTEENTH-CENTURY SUFFOLK by DAVID DYMOND, M.A., F.S.A. and ROGER VIRGOE, PH.D., F.R.HIST.S. IN THE SESSION of Parliament which met between 27 January and 25 March 1428, the Council governing England during Henry VI's minority asked for subsidies to pay for the continuing war in France and for the safe-keeping of the sea. In response the Commons made three grants.' The first was of tunnage and poundage for a year; the second a grant of 6s. 8d. per knight' s fee, a traditional and by now obsolescent feudal aid; the third was a novel, if not quite unprecedented, tax levied on parishes and not, like the normal fifteenth and tenth, on townships.' The last of these grants is the most interesting. Payment had to be made by each rural parish which had ten households or more. If the living of the church was assessed for clerical taxes at less than ten marks, householders were to pay half a mark (6s. 8d.); if it was assessed at ten marks or more, they were to pay at the rate of one mark (13s. 4d.) for each ten marks' valuation. In boroughs the householders of each parish were to pay at the rate of 2s. for every £1 in the valuation of the living. Those parishes which contained fewer than ten households were exempt from payment. It is not the purpose of this paper to examine the reasons for this peculiar hybrid tax, which was not repeated.' For the local historian the most interesting information in the returns is the listing of exempt parishes with small populations.