Scraping the Sky Verticality in American Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago Neighborhood Resource Directory Contents Hgi

CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD [ RESOURCE DIRECTORY san serif is Univers light 45 serif is adobe garamond pro CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY CONTENTS hgi 97 • CHICAGO RESOURCES 139 • GAGE PARK 184 • NORTH PARK 106 • ALBANY PARK 140 • GARFIELD RIDGE 185 • NORWOOD PARK 107 • ARCHER HEIGHTS 141 • GRAND BOULEVARD 186 • OAKLAND 108 • ARMOUR SQUARE 143 • GREATER GRAND CROSSING 187 • O’HARE 109 • ASHBURN 145 • HEGEWISCH 188 • PORTAGE PARK 110 • AUBURN GRESHAM 146 • HERMOSA 189 • PULLMAN 112 • AUSTIN 147 • HUMBOLDT PARK 190 • RIVERDALE 115 • AVALON PARK 149 • HYDE PARK 191 • ROGERS PARK 116 • AVONDALE 150 • IRVING PARK 192 • ROSELAND 117 • BELMONT CRAGIN 152 • JEFFERSON PARK 194 • SOUTH CHICAGO 118 • BEVERLY 153 • KENWOOD 196 • SOUTH DEERING 119 • BRIDGEPORT 154 • LAKE VIEW 197 • SOUTH LAWNDALE 120 • BRIGHTON PARK 156 • LINCOLN PARK 199 • SOUTH SHORE 121 • BURNSIDE 158 • LINCOLN SQUARE 201 • UPTOWN 122 • CALUMET HEIGHTS 160 • LOGAN SQUARE 204 • WASHINGTON HEIGHTS 123 • CHATHAM 162 • LOOP 205 • WASHINGTON PARK 124 • CHICAGO LAWN 165 • LOWER WEST SIDE 206 • WEST ELSDON 125 • CLEARING 167 • MCKINLEY PARK 207 • WEST ENGLEWOOD 126 • DOUGLAS PARK 168 • MONTCLARE 208 • WEST GARFIELD PARK 128 • DUNNING 169 • MORGAN PARK 210 • WEST LAWN 129 • EAST GARFIELD PARK 170 • MOUNT GREENWOOD 211 • WEST PULLMAN 131 • EAST SIDE 171 • NEAR NORTH SIDE 212 • WEST RIDGE 132 • EDGEWATER 173 • NEAR SOUTH SIDE 214 • WEST TOWN 134 • EDISON PARK 174 • NEAR WEST SIDE 217 • WOODLAWN 135 • ENGLEWOOD 178 • NEW CITY 219 • SOURCE LIST 137 • FOREST GLEN 180 • NORTH CENTER 138 • FULLER PARK 181 • NORTH LAWNDALE DEPARTMENT OF FAMILY & SUPPORT SERVICES NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY WELCOME (eU& ...TO THE NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY! This Directory has been compiled by the Chicago Department of Family and Support Services and Chapin Hall to assist Chicago families in connecting to available resources in their communities. -

Early 'Urban America'

CCAPA AICP Exam Presentation Planning History, Theory, and Other Stuff Donald J. Poland, PhD, AICP Senior VP & Managing Director, Urban Planning Goman+York Property Advisors, LLC www.gomanyork.com East Hartford, CT 06108 860-655-6897 [email protected] A Few Words of Advice • Repetitive study over key items is best. • Test yourself. • Know when to stop. • Learn how to think like the test writers (and APA). • Know the code of ethics. • Scout out the test location before hand. What is Planning? A Painless Intro to Planning Theory • Rational Method = comprehensive planning – Myerson and Banfield • Incremental (muddling through) = win little battles that hopefully add up to something – Charles Lindblom • Transactive = social development/constituency building • Advocacy = applying social justice – Sherry Arnstein’s Ladder of Public Participation – Paul Davidoff – advocacy planning American Planning before 1800 • European Traditions – New England, New Amsterdam, & the village tradition – Tidewater and the ‘Town Acts’ – The Carolinas/Georgia and the Renaissance Style – L’Enfant, Washington D.C., & Baroque Style (1791) • Planning was Architectural • Planning was plotting street layouts • There wasn’t much of it… The 1800’s and Planning Issues • The ‘frontier’ is more distant & less appealing • Massive immigration • Industrialization & Urbanization • Problems of the Industrial City – Poverty, pollution, overcrowding, disease, unrest • Planning comes to the rescue – NYC as epicenter – Central Park 1853 – 1857 (Olmsted & Vaux) – Tenement Laws Planning Prior to WWI • Public Awareness of the Problems – Jacob Riis • ‘How the Other Half Lives’ (1890) • Exposed the deplorable conditions of tenement house life in New York City – Upton Sinclair • ‘The Jungle’ (1905) – William Booth • The Salvation Army (1891) • Solutions – Zoning and the Public Health Movement – New Towns, Garden Cities, and Streetcar Suburbs – The City Beautiful and City Planning Public Health Movement • Cities as unhealthy places – ‘The Great Stink’, Cholera, Tuberculosis, Alcoholism…. -

Chicago from 1871-1893 Is the Focus of This Lecture

Chicago from 1871-1893 is the focus of this lecture. [19 Nov 2013 - abridged in part from the course Perspectives on the Evolution of Structures which introduces the principles of Structural Art and the lecture Root, Khan, and the Rise of the Skyscraper (Chicago). A lecture based in part on David Billington’s Princeton course and by scholarship from B. Schafer on Chicago. Carl Condit’s work on Chicago history and Daniel Hoffman’s books on Root provide the most important sources for this work. Also Leslie’s recent work on Chicago has become an important source. Significant new notes and themes have been added to this version after new reading in 2013] [24 Feb 2014, added Sullivan in for the Perspectives course version of this lecture, added more signposts etc. w.r.t to what the students need and some active exercises.] image: http://www.richard- seaman.com/USA/Cities/Chicago/Landmarks/index.ht ml Chicago today demonstrates the allure and power of the skyscraper, and here on these very same blocks is where the skyscraper was born. image: 7-33 chicago fire ruins_150dpi.jpg, replaced with same picture from wikimedia commons 2013 Here we see the result of the great Chicago fire of 1871, shown from corner of Dearborn and Monroe Streets. This is the most obvious social condition to give birth to the skyscraper, but other forces were at work too. Social conditions in Chicago were unique in 1871. Of course the fire destroyed the CBD. The CBD is unique being hemmed in by the Lakes and the railroads. -

VILLAGE WIDE ARCHITECTURAL + HISTORICAL SURVEY Final

VILLAGE WIDE ARCHITECTURAL + HISTORICAL SURVEY Final Survey Report August 9, 2013 Village of River Forest Historic Preservation Commission CONTENTS INTRODUCTION P. 6 Survey Mission p. 6 Historic Preservation in River Forest p. 8 Survey Process p. 10 Evaluation Methodology p. 13 RIVER FOREST ARCHITECTURE P. 18 Architectural Styles p. 19 Vernacular Building Forms p. 34 HISTORIC CONTEXT P. 40 Nineteenth Century Residential Development p. 40 Twentieth Century Development: 1900 to 1940 p. 44 Twentieth Century Development: 1940 to 2000 p. 51 River Forest Commercial Development p. 52 Religious and Educational Buildings p. 57 Public Schools and Library p. 60 Campuses of Higher Education p. 61 Recreational Buildings and Parks p. 62 Significant Architects and Builders p. 64 Other Architects and Builders of Note p. 72 Buildings by Significant Architect and Builders p. 73 SURVEY FINDINGS P. 78 Significant Properties p. 79 Contributing Properties to the National Register District p. 81 Non-Contributing Properties to the National Register District p. 81 Potentially Contributing Properties to a National Register District p. 81 Potentially Non-Contributing Properties to a National Register District p. 81 Noteworthy Buildings Less than 50 Years Old p. 82 Districts p. 82 Recommendations p. 83 INVENTORY P. 94 Significant Properties p. 94 Contributing Properties to the National Register District p. 97 Non-Contributing Properties to the National Register District p. 103 Potentially Contributing Properties to a National Register District p. 104 Potentially Non-Contributing Properties to a National Register District p. 121 Notable Buildings Less than 50 Years Old p. 125 BIBLIOGRAPHY P. 128 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS RIVER FOREST HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSION David Franek, Chair Laurel McMahon Paul Harding, FAIA Cindy Mastbrook Judy Deogracias David Raino-Ogden Tom Zurowski, AIA PROJECT COMMITTEE Laurel McMahon Tom Zurowski, AIA Michael Braiman, Assistant Village Administrator SURVEY TEAM Nicholas P. -

Directions to the Chicago Office

Directions to the Chicago Office 70 W. Madison St. Suite 3100 Chicago, IL 60602 P: +1: 312.372.1121 Nearby Subways: CTA Blue train – exit at Dearborn & Monroe CTA Red train – exit at Monroe & State street CTA Green, Brown, Orange, Pink, Purple trains – exit Madison & Wabash Metra Electric, South Shore trains – exit at Millennium Station Metra Rock Island Train – exit at LaSalle street station Metra South West, Heritage Corridor, BNSF , Milwaukee West, North, North Central trains – exit at Union Station Metra Union Pacific North, Union Pacific West, Union Pacific NW trains – exit at Ogilvie Station Nearby Buses: CTA 14 Jeffrey Express, 19 United Center Express, 20 Madison, 20x Washington/Madison Express – stops in front of the building on Madison CTA 22 Clark, 24 Wentworth, 129 West Loop/South Loop ‐ stops on the corner of Clark and Madison CTA 22 Clark, 24 Wentworth, 36 Broadway, 52 Archer, 129 West Loop/South Loop‐ stops on the corner of Dearborn and Madison From O’Hare Airport – • Take I‐190 E ramp • Continue onto I‐90E (Kennedy expressway) for 13.6 miles • Exit 51H‐I (I‐290W, Eishenhower expressway) • Take exit 51I (Congress Pkwy, Chicago Loop) on the left • Continue onto W. Congress Pkwy • Take Wacker Drive (Franklin Street) exit on the right • Take Wacker Drive ramp on the left • Continue onto S Upper Wacker Drive • Turn right onto W. Monroe Street • Turn left onto S. Dearborn Street • Turn left onto W. Madison Street From Midway Airport – • Go south on IL‐50 S (S. Cicero Av) • Make a U‐turn onto IL‐50 N (S. -

Reciprocal Sites Membership Program

2015–2016 Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Membership Program The Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Program includes 30 historic sites across the United States. FLWR on your membership card indicates that you enjoy the National Reciprocal sites benefit. Benefits vary from site to site. Please check websites listed in this brochure for detailed information on each site. ALABAMA ARIZONA CALIFORNIA FLORIDA 1 Rosenbaum House 2 Taliesin West 3 Hollyhock House 4 Florida Southern College 601 RIVERVIEW DRIVE 12621 N. FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BLVD BARNSDALL PARK 750 FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT WAY FLORENCE, AL 35630 SCOTTSDALE, AZ 85261-4430 4800 HOLLYWOOD BLVD LAKELAND, FL 33801 256.718.5050 480.860.2700 LOS ANGELES, CA 90027 863.680.4597 ROSENBAUMHOUSE.COM FRANKLLOYDWRIGHT.ORG 323.644.6269 FLSOUTHERN.EDU/FLW WRIGHTINALABAMA.COM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION BARNSDALL.ORG FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: 9AM–4PM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: TOUR HOURS: BOOKSHOP HOURS: 8:30AM–6PM TOUR HOURS: THURS–SUN, 11AM–4PM OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT TOUR TICKETS AVAILABLE AT THE THANKSGIVING, CHRISTMAS AND NEW Experience firsthand Frank Lloyd MAJOR HOLIDAYS. HOLLYHOCK HOUSE VISITOR’S CENTER YEAR’S DAY. 10AM–4PM Wright’s brilliant ability to integrate TUES–SAT, 10AM–4PM IN BARNSDALL PARK. VISITOR CENTER & GIFT SHOP HOURS: SUN, 1PM–4PM indoor and outdoor spaces at Taliesin Hollyhock House is Wright’s first 9:30AM–4:30PM West—Wright’s winter home, school The Rosenbaum House is the only Los Angeles project. Built between and studio from 1937-1959, located Discover the largest collection of Frank Lloyd Wright-designed 1919 and 1923, it represents his on 600 acres of dramatic desert. -

Hotel-Map.Pdf

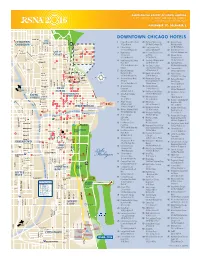

RADIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF NORTH AMERICA 102ND SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY AND ANNUAL MEETING McCORMICK PLACE, CHICAGO NOVEMBER 27 – DECEMBER 2 DOWNTOWN CHICAGO HOTELS OLD CLYBOURN 1 Palmer House Hilton Hotel 28 Fairmont Hotel Chicago 61 Monaco Chicago, CORRIDOR TOWN 17 East Monroe 200 North Columbus Dr. A Kimpton Hotel 2 Hilton Chicago 29 Four Seasons Hotel 225 North Wabash 23 720 South Michigan Ave. 120 East Delaware Pl. 62 Omni Chicago Hotel GOLD 60 70 3 Hyatt Regency 30 Freehand Chicago Hostel 676 North Michigan Ave. COAST 29 87 38 66 Chicago Hotel and Hotel 63 Palomar Chicago, 89 68 151 East Wacker Dr. 19 East Ohio St. A Kimpton Hotel 80 47 4 Hyatt Regency McCormick 31 The Gray, A Kimpton Hotel 505 North State St. Place Hotel 122 W. Monroe St. 64 Park Hyatt Hotel 2233 South Martin Luther 32 The Gwen, a Luxury 800 North Michigan Ave. King Dr. Collection Hotel, Chicago 65 Peninsula Hotel 5 Marriott Downtown 521 North Rush St. 108 East Superior St. 79 Magnificent Mile 33 Hampton Inn & Suites 66 Public Chicago 86 540 North Michigan Ave. 33 West Illinois St. 78 1301 North State Pkwy. Sheraton Chicago Hotel Hampton Inn Chicago 75 6 34 67 Radisson Blu Aqua & Towers Downtown Magnificent Mile 73 Hotel Chicago 301 East North Water St. 160 East Huron 221 N. Columbus Dr. 64 7 AC Hotel Chicago 35 Hampton Majestic 68 Raffaello Hotel NEAR 65 59 Downtown 22 West Monroe St. 201 East Delaware Pl. 62 10 34 42 630 North Rush St. NORTH 36 Hard Rock Hotel Chicago 69 Renaissance Chicago 46 21 MAGNIFICENT 230 North Michigan Ave. -

Lbbert Wayne Wamer a Thesis Presented to the Graduate

I AN ANALYSIS OF MULTIPLE USE BUILDING; by lbbert Wayne Wamer A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Committee of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Science in Civil Engineering Lehigh University 1982 TABLE OF CCNI'ENTS ABSI'RACI' 1 1. INTRODlCI'ICN 2 2. THE CGJCEPr OF A MULTI-USE BUILDING 3 3. HI8rORY AND GRami OF MULTI-USE BUIIDINCS 6 4. WHY MULTI-USE BUIIDINCS ARE PRACTICAL 11 4.1 CGVNI'GJN REJUVINATICN 11 4. 2 EN'ERGY SAVIN CS 11 4.3 CRIME PREVENTIOO 12 4. 4 VERI'ICAL CANYOO EFFECT 12 4. 5 OVEOCRO'IDING 13 5. DESHN CHARACTERisriCS OF MULTI-USE BUILDINCS 15 5 .1 srRlCI'URAL SYSI'EMS 15 5. 2 AOCHITECI'URAL CHARACTERisriCS 18 5. 3 ELEVATOR CHARACTERisriCS 19 6. PSYCHOI..OCICAL ASPECTS 21 7. CASE srUDIES 24 7 .1 JOHN HANCOCK CENTER 24 7 • 2 WATER TOiVER PlACE 25 7. 3 CITICORP CENTER 27 8. SUMMARY 29 9. GLOSSARY 31 10. TABLES 33 11. FIGJRES 41 12. REFERENCES 59 VITA 63 iii ACKNCMLEI)(}IIENTS The author would like to express his appreciation to Dr. Lynn S. Beedle for the supervision of this project and review of this manuscript. Research for this thesis was carried out at the Fritz Engineering Laboratory Library, Mart Science and Engineering Library, and Lindennan Library. The thesis is needed to partially fulfill degree requirenents in Civil Engineering. Dr. Lynn S. Beedle is the Director of Fritz Laboratory and Dr. David VanHom is the Chainnan of the Department of Civil Engineering. The author wishes to thank Betty Sumners, I:olores Rice, and Estella Brueningsen, who are staff menbers in Fritz Lab, for their help in locating infonnation and references. -

The Rookery Building and Chicago-Kent

Chicago-Kent College of Law Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law 125th Anniversary Materials 125th Anniversary 2-23-2013 The Rookery Building and Chicago-Kent A. Dan Tarlock Chicago-Kent College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/docs_125 Part of the Legal Commons, Legal Education Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Tarlock, A. Dan, "The Rookery Building and Chicago-Kent" (2013). 125th Anniversary Materials. 12. https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/docs_125/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 125th Anniversary at Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in 125th Anniversary Materials by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 14 Then & Now: Stories of Law and Progress Rookery Building, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress. THE ROOKERY BUILDING AND CHICAGO-KENT A. Dan Tarlock hicago-Kent traces its ori- sustain Chicago as a world city, thus gin to the incorporation of making it an attractive and exciting the Chicago College of Law in place to practice law to the benefit C1888. Chicago-Kent’s founding coin- of all law schools in Chicago in- cided with the opening of the Rook- cluding Chicago-Kent. ery Building designed by the preem- The Rookery is now a classic ex- inent architectural firm of Burnham ample of the first school of Chica- and Root. There is a direct connec- go architecture which helped shape tion between the now iconic Rook- modern Chicago and continues to ery Building, located at Adams and make Chicago a special place, de- LaSalle, and the law school building spite decades of desecration of this further west on Adams. -

QUES in ARCH HIST I Jump to Today Questions in Architectural History 1

[email protected] - QUES IN ARCH HIST I Jump to Today Questions in Architectural History 1 Faculty: Zeynep Çelik Alexander, Reinhold Martin, Mabel O. Wilson Teaching Fellows: Oskar Arnorsson, Benedict Clouette, Eva Schreiner Thurs 11am-1pm Fall 2016 This two-semester introductory course is organized around selected questions and problems that have, over the course of the past two centuries, helped to define architecture’s modernity. The course treats the history of architectural modernity as a contested, geographically and culturally uncertain category, for which periodization is both necessary and contingent. The fall semester begins with the apotheosis of the European Enlightenment and the early phases of the industrial revolution in the late eighteenth century. From there, it proceeds in a rough chronology through the “long” nineteenth century. Developments in Europe and North America are situated in relation to worldwide processes including trade, imperialism, nationalism, and industrialization. Sequentially, the course considers specific questions and problems that form around differences that are also connections, antitheses that are also interdependencies, and conflicts that are also alliances. The resulting tensions animated architectural discourse and practice throughout the period, and continue to shape our present. Each week, objects, ideas, and events will move in and out of the European and North American frame, with a strong emphasis on relational thinking and contextualization. This includes a historical, relational understanding of architecture itself. Although the Western tradition had recognized diverse building practices as “architecture” for some time, an understanding of architecture as an academic discipline and as a profession, which still prevails today, was only institutionalized in the European nineteenth century. -

2021 Chicago Hotels

2021 PEI CONVENTION AT THE NACS SHOW - CHICAGO, IL - OCTOBER 5 - 8, 2021 2021 PEI HOTELS ARE INCDICATED IN RED 2021 CHICAGO HOTELS 1 21c Museum Hotel Chicago 23 Hotel EMC2, Autograph Collection 2 AC Hotel Chicago Downtown 24 Hyatt Centric Chicago Magnificent Mile 3 Allerton Warwick Hotel 25 Hyatt Place Chicago River 4 Aloft Chicago Downtown North River North 26 Hyatt Regency Chicago 44 5 Cambria Hotel Chicago 31 40 48 46 Loop 27 Hyatt Regency McCormick Place PEI HQ HOTEL 6 Chicago Marriott Downtown Magnificent Mile 28 InterContinental Chicago 3 15 21 Magnificent Mile 33 7 2 24 11 Courtyard Chicago 23 48 1 10 8 Downtown/River North 29 LondonHouse Chicago 6 32 18 4 28 9 8 25 12 Doubletree Chicago 30 Marriott Marquis Chicago 7 41 Magnificent Mile McCormick Place 37 39 22 29 26 9 Embassy Suites by Hilton 31 Millennium Knickerbocker 38 42 16 36 Chicago Downtown 13 35 Magnificent Mile 32 Moxy Chicago Downtown 5 10 Embassy Suites Chicago 33 Omni Chicago Hotel - An All Downtown Suite Property 45 34 11 Fairfield Inn & Suites 34 Palmer House Hilton Chicago Downtown/ Magnificent Mile 35 Radisson Blu Aqua Hotel Chicago 12 Fairfield Inn & Suites Chicago Downtown/ 36 Renaissance Chicago RiverNorth Downtown Hotel 13 Fairmont Chicago 37 Residence Inn Chicago 43 Millennium Park Downtown Magnificent Mile 17 14 Hampton Inn by Hilton 38 Residence Inn Chicago Chicago McCormick Place Downtown River North 15 Hampton Inn Chicago 39 Royal Sonesta Chicago Downtown Magnificent Mile Riverfront 16 Hampton Inn Chicago 40 Sheraton Grand Chicago Downtown/N Loop/ Michigan Ave 41 SpringHill Suites Chicago River North 17 Hilton Chicago 42 Swissôtel Chicago 18 Hilton Garden Inn 43 The Blackstone Hotel, 19 Hilton Garden Inn Chicago Autograph Collection McCormick Place 44 The Drake, a Hilton Hotel 20 Home 2 Suites by Hilton 31 Chicago McCormick Place 45 The Silversmith Hotel & 21 20 15 Suites 28 21 Homewood Suites by Hilton Chicago Magnificent Mile 46 The Talbott Hotel 22 Hotel Chicago, A Marriott 47 W Chicago Lakeshore Autograph Collection Hotel 48 Westin Michigan Avenue Chicago. -

Read More and Download The

Case Study: Vista Tower, Chicago A New View, and a New Gateway, for Chicago Abstract Upon completion, Vista Tower will become Chicago’s third tallest building, topping out the Lakeshore East development, where the Chicago River meets Lake Michigan. Juliane Wolf will participate in the Session 7C panel discussion High-Rise Occupying a highly visible site on a north- Design Drivers: Now to 2069, on Jeanne Gang Juliane Wolf south view corridor within the city’s grid, and in Wednesday, 30 October. Vista Tower is the subject of the off-site close proximity to the Loop, the river, and the program on Thursday, Authors city’s renowned lakefront park system, this 31 October. Jeanne Gang, Founding Principal and Partner Juliane Wolf, Design Principal and Partner mixed-use supertall building with a porous Studio Gang 1520 West Division Street base is simultaneously a distinctive landmark Chicago, IL 60642 USA at the scale of the city and a welcoming connector at the ground plane. Clad in a t: +1 773 384 1212 gradient of green-blue glass and supported by a reinforced concrete structure, the e: [email protected] studiogang.com tower is composed of an interconnected series of stacked, frustum-shaped volumes that move rhythmically in and out of plane and extend to various heights. The Jeanne Gang, architect and MacArthur Fellow, is the Founding Principal and Partner of Studio tower is lifted off the ground plane at the center, creating a key gateway for Gang, an architecture and urban design practice headquartered in Chicago with offices in New York, pedestrians accessing the Riverwalk from Lakeshore East Park.