Of Invasive Alien Species (IAS) Status and Management Federation of St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

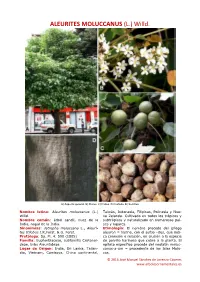

ALEURITES MOLUCCANUS (L.) Willd

ALEURITES MOLUCCANUS (L.) Willd. A) Aspecto general. B) Flores. C) Frutos. D) Corteza. E) Semillas Nombre latino: Aleurites moluccanus (L.) Taiwán, Indonesia, Filipinas, Polinesia y Nue- Willd. va Zelanda. Cultivado en todos los trópicos y Nombre común: árbol candil, nuez de la subtrópicos y naturalizado en numerosos paí- India, nogal de la India. ses y lugares. Sinonimias: Jatropha moluccana L., Aleuri- Etimología: El nombre procede del griego tes trilobus J.R.Forst. & G. Forst. aleuron = harina, con el sufijo –ites, que indi- Protólogo: Sp. Pl. 4: 590 (1805) ca conexión o relación, en alusión a la especie Familia: Euphorbiaceae, subfamilia Crotonoi- de polvillo harinoso que cubre a la planta. El deae, tribu Aleuritideae. epíteto específico procede del neolatín moluc- Lugar de Origen: India, Sri Lanka, Tailan- canus-a-um = procedente de las Islas Molu- dia, Vietnam, Camboya, China continental, cas. © 2016 José Manuel Sánchez de Lorenzo‐Cáceres www.arbolesornamentales.es Descripción: árbol siempreverde, monoico, obovoides, comprimidas dorsiventralmente, de 5-10 m de altura en cultivo, pudiendo al- de 2,3-3,2 x 2-3 cm, grisáceas con moteado canzar más de 30 en sus zonas de origen, con castaño. el tronco recto y la corteza lisa, grisácea o castaño rojiza, con lenticelas y fisurada con el Fenología: aunque dependiendo del clima paso del tiempo; copa frondosa, más o menos tiene flores y frutos gran parte del año, flore- piramidal, con las ramillas jóvenes puberulen- ce mayormente de Abril a Noviembre y fructi- tas, con indumento de pelos estrellados grisá- fica de Octubre a Diciembre, permaneciendo ceos o plateado-amarillentos, a veces algo los frutos en el árbol casi un año sin abrir, rojizos. -

New Records of Some Pests of the Coconut Inflorescence and Developing Fruit and Their Natural Enemies in Sri Lanka

COCOS, (1987) 5, 39—42 Printed in Sri Lanka New Records of some Pests of the Coconut Inflorescence and Developing Fruit and Their Natural Enemies in Sri Lanka L. C. P. FERNANDO and P. KANAGARATNAM Coconut Research Institute, Lunuwila, Sri Lanka. ABSTRACT A survey was carried out at Bandirippuwa Estate, Kirimetiyana Estate and at Isolated Seed Garden, Rajakadaluwa for the pests of coconut inflorescence and developing fruits. The mite, Dolichotetranychus sp. (Tenuipalpidae) which lives beneath the perianth and feeds on the epicarp, causes considerable damage to the developing fruit. Bi-monthly observations on the intensity of infestation of nuts among different forms of coconut indicated a significant difference among forms in their susceptibility to mite damage. Pseudococcus cocotis (Maskell) (Pseudococcidae), Pseudococcus citriculus Green (Pseudococcidae) and Planococcus lilacinus (Cockereli) (Pseudococcidae), when feeding in large numbers on the peduncle, cause button nut shedding and drying up of the inflo rescence. The parasitoids and predators of these mealybugs recorded for the first time in Sri Lanka are Promuscidea unfasciativentris Girault (Aphelinidae) Platygaster sp. (Platygastridae), Anagyrus sp. nr. pseudococci (Girault) (Encyrtidae) Coccodiplosis sp. (Cecidomyiidae), Cryptogonus bryanti Kapur (Coccinellidae) and Pseudoscymnus sp. (Coccinellidae). Several species of scale insects namely, Coccus hesperidum (Linnaeus) (Coccidae) Aulacaspis sp. (Diaspididae), Pseudaulacaspis cockerelli (Cooley) (Diaspididae), Aoni- diella orientalis (Newstead) (Diaspididae), and Pinnaspis strachani (Cooley) (Diaspididae) are recorded as minor pests of the developing fruits of coconut. Coccophagus silvestrii Compere (Aphelinidae), Scymnus sp. (Coccinellidae), Pseudoscymnus sp. (Coccinellidae) Telsimia ceylonica (Weise) (Coccinellidae), Cryptogonus bryanti Kapur (Coccinellidae) and Cybocephalus sp. (Nitidulidae) are recorded as their parasitoids and predators. These natural enemies are probably responsible for the control of these pests in the field. -

Cosmetic Ingredients Found Safe As Used (1398 Total, Through February, 2012)

Cosmetic ingredients found safe as used (1398 total, through February, 2012) Ingredient # "As used" concentration for safe as used conclusion Acacia Senegal Gum and Acacia Senegal Gum Extract 2 up to 9% Acetic Acid 1 up to 0.3% Acetylated Lanolin 1 up to 7% Acetylated Lanolin Alcohol 1 up to 16% Acetyl Tributyl Citrate 1 up to 7% Acetyl Triethyl Citrate 1 up to 7% Acetyl Trihexyl Citrate 1 not in use at the time* Acetyl Trioctyl Citrate 1 not in use at the time* Acrylates/Dimethiconol Acrylate Copolymer (Dimethiconol and its Esters and Reaction Products) 1 up to 0.5% Actinidia Chinensis (Kiwi) Seed Oil 1 up to 0.1% Adansonia Digitata Oil 1 up to 0.01% Adansonia Digitata Seed Oil 1 not in use at the time* Adipic Acid (Dicarboxylic Acids and their Salts and Esters) 1 0.000001% in leave on; 18% in rinse off Alcohol Denat. denatured with t-Butyl Alcohol, Denatonium Benzoate, Diethyl Phthalate, or Methyl 4 up to 99% Alcohol Aleurites Moluccanus Bakoly Seed Oil 1 not in use at the time* Aleurities Moluccana Seed Oil 1 0.00001 to 5% Allantoin 1 up to 2% Allantoin Ascorbate 1 up to 0.05% Allantoin Biotin and Allantoin Galacturonic Acid 2 not in use at the time* Allantoin Glycyrrhetinic Acid, Allantoin Panthenol, and Allantoin Polygalacturonic Acid 3 concentration not reported* Almond Meal (aka- Prunus Amygdalus Dulcis) Alumnina Magnesium Silicate 1 up to 0.01% Alumnium Calcium Silicate 1 up to 6% Aluminum Dimyristate 1 up to 3% Aluminum Distearate 1 up to 5% Aluminum Iron Silicates 1 not in use at the time* Aluminum Isostearates/Myristates, Calcium -

New Data on the Whiteflies (Insecta: Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) of Montenegro, Including Three Species New for the Country

Acta entomologica serbica, 2015, 20: 29-41 UDC 595.754(497.16)"2012" DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.44654 NEW DATA ON THE WHITEFLIES (INSECTA: HEMIPTERA: ALEYRODIDAE) OF MONTENEGRO, INCLUDING THREE SPECIES NEW FOR THE COUNTRY CHRIS MALUMPHY1, SANJA RADONJIĆ2, SNJEŽANA HRNČIĆ2 and M ILORAD RAIČEVIĆ2 1 The Food and Environment Research Agency, Sand Hutton, YO41 1LZ, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] 2 Biotechnical Faculty of the University of Montenegro, Podgorica, Montenegro Abstract Collection data on nine species of whitefly collected in the coastal and central regions of Montenegro during October 2012 are presented. Three species are recorded from Montenegro for the first time: Aleuroclava aucubae (Kuwana), Aleurotuba jelinekii (Frauenfeld) and Bemisia afer (Priesner & Hosny) complex. Two of the species, A. aucubae and B. afer complex were found in Tološi, on Citrus sp. and Laurus nobilis, respectively. Aleurotuba jelinekii was found in Podgorica on Viburnum tinus. KEY WORDS: Whiteflies, Aleyrodidae, Montenegro Introduction Whiteflies comprise a single family, Aleyrodidae, which currently contains 1556 extant species in 161 genera (Martin & Mound, 2007). Fifty-six species occur outdoors in Europe and the Mediterranean basin (Martin et al., 2000). All whiteflies are phytophagous and have three developmental stages: egg, larval (with four larval instars) and adult. Many species are economically important plant pests of outdoor crops, ornamentals and indoor plantings. Feeding by immature whiteflies reduces plant vigor by depletion of plant sap, and foliage becomes contaminated with eliminated honeydew on which black sooty mold grows, thereby reducing the photosynthetic area and lowering the aesthetic appearance of ornamentals. Adults of a small number of species, most notably Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius), are important vectors of plant viruses (Jones, 2003). -

Pharmacognostical and Physico–Chemical Standardization of Leaves of Caesalpinia Pulcherrima

IJRPC 2011, 1(4) Pawar et al. ISSN: 22312781 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH IN PHARMACY AND CHEMISTRY Available online at www.ijrpc.com Research Article PHARMACOGNOSTICAL AND PHYSICO–CHEMICAL STANDARDIZATION OF LEAVES OF CAESALPINIA PULCHERRIMA C. R. Pawar1*, R. B. Kadtan1, A. A. Gaikwad1 and D. B. Kadtan2 1S.N.D. College of Pharmacy, Babhulgaon, Yeola, Nasik (Dt.), Maharashtra, India. 2R.C. Patel institute of pharmacy, Shirpur, Dhule, Maharashtra, India. *Corresponding Author: [email protected] ABSTRACT Caesalpinia pulcherrima belonging to family Caesalpiniaceae is distributed throught out India. Commonly it is known as Peacock-flower. Plant shows diterpenoids, isovouacaperol, sitosterol and flavonoids. The plant is considered as emmenagogue, purgative and stimulant, abotificient and also used in bronchitis, asthma and malarial fever, leaves used as antipyretic, antimicrobial. Flower also shows antioxidant and antiviral activity. The present study deals with the macroscopical and microscopical studies of Caesalpinia pulcherrima leaf. Macroscopically, the Caesalpinia pulcherrima is compound leaf, ovate shape, entire margin and glabrous surface, asymmetrical base, small petiole. The microscopic study showed presence of collenchyma, vascular bundle, spongy parenchyma, palisade cells, stomata. Some distinct characters were observed while studying the transverse sections. Physiochemical studies revealed total ash, acid insoluble ash, water insoluble ash, loss on drying, alcohol soluble extractive, water soluble extractive and preliminary phytochemical studies of the leaves were also carried out. The present study might be useful to supplement information in regard to its identification parameters. Keywords: Caesalpinia pulcherrima, physico-chemical analysis, phytochemical study. INTRODUCTION diterpenoids, isovouacaperol, sitosterol also Caesalpinia pulcherrima is also known as present. Caesalpinia pulcherrima is used for a peacock flower1 is the type of genus fabaceae various purpose of herbal medicine. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

EVALUATION OF Rhyzobius lophanthae (BLAISDELL) AND Cryptolaemus montrouzieri MULSANT (COLEOPTERA: COCCINELLIDAE) AS PREDATORS OF Aulacaspis yasumatsui TAKAGI (HEMIPTERA: DIASPIDIDAE) By GRETA THORSON A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2009 1 © 2009 Greta Thorson 2 To my family for their constant support and encouragement, as well as past and present colleagues and mentors who helped inspire me along the way 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my family for their enthusiasm in helping me collect insects and willingness to store countless specimens in their freezers over the years. I’d especially like to thank my major professor and committee members for lending their experience and encouragement. I’d like to also thank my past mentors who inspired me to pursue entomology as a profession. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 LIST OF TABLES...........................................................................................................................7 LIST OF FIGURES .........................................................................................................................8 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS........................................................................................................10 ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................................11 -

EPPO Reporting Service, 1996, No. 2

EPPO Reporting Service Paris, 1996-01-02 Reporting Service 1996, No. 02 CONTENTS 96/021 - EPPO Electronic Documentation Service 96/022 - Situation of Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) solanacearum in France and Portugal 96/023 - Fireblight foci in Puy-de-Dôme (FR) 96/024 - Toxoptera citricida found in Florida (US) 96/025 - Hyphantria cunea found in Tessin (CH) 96/026 - Bactrocera dorsalis trapped in California and Florida (US) 96/027 - Anastrepha ludens trapped in California (US) 96/028 - Further spread of Maconellicoccus hirsutus in the Caribbean 96/029 - Tilletia controversa is not present in Germany 96/030 - Present situation of citrus tristeza closterovirus in Spain 96/031 - Citrus whiteflies in Spain 96/032 - Proposed names for citrus greening bacterium and lime witches' broom phytoplasma 96/033 - Report of phytoplasma infection in European plums in Italy 96/034 - Susceptibility of potato cultivars to Synchytrium endobioticum 96/035 - Specific ELISA detection of the Andean strain of potato S carlavirus 96/036 - NAPPO quarantine lists for potato pests 96/037 - Studies on the possible use of sulfuryl fluoride fumigation against Ceratocystis fagacearum 96/038 - Treatments of orchid blossoms against Thrips palmi and Frankliniella occidentalis 96/039 - Soil solarization to control Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis 96/040 - Metcalfa pruinosa: a new pest in Europe 96/041 - Phytophthora disease of common alder 96/042 - Potential spread of Artioposthia triangulata (New Zealand flatworm) and Australoplana sanguinea var. alba to continental Europe EPPO Reporting Service 96/021 EPPO Electronic Documentation Service EPPO Electronic Documentation is a new service developed by EPPO to make documents available in electronic form to EPPO correspondents. -

Report and Recommendations on Cycad Aulacaspis Scale, Aulacaspis Yasumatsui Takagi (Hemiptera: Diaspididae)

IUCN/SSC Cycad Specialist Group – Subgroup on Invasive Pests Report and Recommendations on Cycad Aulacaspis Scale, Aulacaspis yasumatsui Takagi (Hemiptera: Diaspididae) 18 September 2005 Subgroup Members (Affiliated Institution & Location) • William Tang, Subgroup Leader (USDA-APHIS-PPQ, Miami, FL, USA) • Dr. John Donaldson, CSG Chair (South African National Biodiversity Institute & Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden, Cape Town, South Africa) • Jody Haynes (Montgomery Botanical Center, Miami, FL, USA)1 • Dr. Irene Terry (Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA) Consultants • Dr. Anne Brooke (Guam National Wildlife Refuge, Dededo, Guam) • Michael Davenport (Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, Miami, FL, USA) • Dr. Thomas Marler (College of Natural & Applied Sciences - AES, University of Guam, Mangilao, Guam) • Christine Wiese (Montgomery Botanical Center, Miami, FL, USA) Introduction The IUCN/SSC Cycad Specialist Group – Subgroup on Invasive Pests was formed in June 2005 to address the emerging threat to wild cycad populations from the artificial spread of insect pests and pathogens of cycads. Recently, an aggressive pest on cycads, the cycad aulacaspis scale (CAS)— Aulacaspis yasumatsui Takagi (Hemiptera: Diaspididae)—has spread through human activity and commerce to the point where two species of cycads face imminent extinction in the wild. Given its mission of cycad conservation, we believe the CSG should clearly focus its attention on mitigating the impact of CAS on wild cycad populations and cultivated cycad collections of conservation importance (e.g., Montgomery Botanical Center). The control of CAS in home gardens, commercial nurseries, and city landscapes is outside the scope of this report and is a topic covered in various online resources (see www.montgomerybotanical.org/Pages/CASlinks.htm). -

Your Name Here

PISTAS QUIMIOSSENSORIAIS DE PREDADORES E CONCORRENTES INFLUENCIANDO NA BUSCA POR REFÚGIO NO FRUTO PELO ÁCARO DO COQUEIRO Aceria guerreronis KEIFER (ACARI: ERIOPHYIDAE) por ÉRICA COSTA CALVET (Sob Orientação do Professor Manoel Guedes Correa Gondim Jr. – UFRPE) RESUMO Os organismos são adaptados para reconhecer pistas ambientais que podem fornecer informações sobre risco de predação ou competição. Os ácaros eriofiídeos não-vagrantes evitam a predação utilizando principalmente habitat de difícil acesso para os predadores (galha, minas ou espaços confinados nas plantas), como a região meristemática do coco, habitada pelos ácaros fitófagos Aceria guerreronis e Steneotarsonemus concavuscutum. O objetivo deste estudo foi investigar a resposta de A. guerreronis às pistas dos predadores Neoseiulus baraki e Amblyseius largoensis em frutos de coco, pistas de coespecíficos (A. guerreronis sacrificado) e pistas do fitófago S. concavuscutum. O ensaio foi realizado liberando cerca de 300 indivíduos de A. guerreronis em um fruto previamente tratados com pistas de predadores ou fitófagos coespecífico ou heteroespecífico. Para cada tratamento, foram feitas 20 repetições. Observamos também o caminhamento de A. guerreronis mediado por pistas químicas no equipamento de filmagem Viewpoint por 10min. A infestação de frutos por A. guerreronis foi maior na presença de pistas de predadores e reduzida na presença de pistas de S. concavuscutum, as pistas de coespecífico sacrificado não interferiram no processo de infestação. Além disso, as pistas testadas também alteraram os parâmetros de caminhamento de A. guerreronis. Ele caminhou mais em resposta a i pistas de predadores e ao fitófago heteroespecífico. Além disso, A. guerreronis teve mais tempo em atividade nos tratamentos com pistas em comparação com o tratamento de controle. -

BACKYARD BUDDIES Information Sheet Chilocorus Circumdatus for Scale

BACKYARD BUDDIES Information Sheet Luke - adult & larvae Chilocorus circumdatus for Scale Red Chilocorus (Luke) is a helmet-shaped ladybird beetle, approximately 5 mm in length. Adults are a rich orange colour with a fine black margin around the base of their wing covers. Adult females lay cylindrical eggs, 1 mm in length, beneath the cover of scale insects. At 25˚C the eggs take about one week to hatch. Chilocorus larvae are voracious feeders and have pronounced spines that cover their body. After ten days or so larvae then migrate to a secluded position and pupate. The adult beetles emerge between seven and nine days later, to mate and lay their eggs. Egg laying starts approximately ten days after emergence. At an optimum temperature of 28˚C, their life cycle takes approximately one month. Chilocorus beetles live for between four and eight weeks. Target pests Armoured scale insects, including: Red scale Aonidiella aurantii Oriental scale Aonidiella orientalis Oleander scale Aspidiotus nerii White louse scale (citrus snow scale) Unaspis citri Scale-eating ladybirds prey on a range of armoured scale insects. Red Chilocorus beetles feed readily on white louse scale (citrus snow scale), oleander scale, oriental and red scale. Scale insects feed by sucking sap from plants. A heavy infestation may cause discolouration, leaf drop and shoot distortion, which can lead to twig dieback and even plant death. Chemical control of scale is difficult because they have hard, waxy protective covers and remain stationary for most of their live. The resistance of scale insects to pesticides is a problem in many regions. -

Preliminary Checklist of Extant Endemic Species and Subspecies of the Windward Dutch Caribbean (St

Preliminary checklist of extant endemic species and subspecies of the windward Dutch Caribbean (St. Martin, St. Eustatius, Saba and the Saba Bank) Authors: O.G. Bos, P.A.J. Bakker, R.J.H.G. Henkens, J. A. de Freitas, A.O. Debrot Wageningen University & Research rapport C067/18 Preliminary checklist of extant endemic species and subspecies of the windward Dutch Caribbean (St. Martin, St. Eustatius, Saba and the Saba Bank) Authors: O.G. Bos1, P.A.J. Bakker2, R.J.H.G. Henkens3, J. A. de Freitas4, A.O. Debrot1 1. Wageningen Marine Research 2. Naturalis Biodiversity Center 3. Wageningen Environmental Research 4. Carmabi Publication date: 18 October 2018 This research project was carried out by Wageningen Marine Research at the request of and with funding from the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality for the purposes of Policy Support Research Theme ‘Caribbean Netherlands' (project no. BO-43-021.04-012). Wageningen Marine Research Den Helder, October 2018 CONFIDENTIAL no Wageningen Marine Research report C067/18 Bos OG, Bakker PAJ, Henkens RJHG, De Freitas JA, Debrot AO (2018). Preliminary checklist of extant endemic species of St. Martin, St. Eustatius, Saba and Saba Bank. Wageningen, Wageningen Marine Research (University & Research centre), Wageningen Marine Research report C067/18 Keywords: endemic species, Caribbean, Saba, Saint Eustatius, Saint Marten, Saba Bank Cover photo: endemic Anolis schwartzi in de Quill crater, St Eustatius (photo: A.O. Debrot) Date: 18 th of October 2018 Client: Ministry of LNV Attn.: H. Haanstra PO Box 20401 2500 EK The Hague The Netherlands BAS code BO-43-021.04-012 (KD-2018-055) This report can be downloaded for free from https://doi.org/10.18174/460388 Wageningen Marine Research provides no printed copies of reports Wageningen Marine Research is ISO 9001:2008 certified. -

Caesalpinia Pulcherrima (Dwarf Poinciana) Size/Shape

Caesalpinia pulcherrima (Dwarf Poinciana) The dwarf Poinciana is a fast growing large shrub or small tree Leaves are bright green bi-pinnate feathery. Flowers are very showy yellow and orange in the middle appearing throughout the year. The fruits are pod. Makes a good specimen and used as barrier. All plant parts are poisonous. Grows well in drained sandy soil and needs full sun. Landscape Information French Name: Césalpinie la plus belle, Petit Flamboyant Pronounciation: sez-al-PIN-ee-uh pul-KAIR- ih-muh Plant Type: Shrub Origin: South America Heat Zones: 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Hardiness Zones: 9, 10, 11, 12 Uses: Specimen, Border Plant, Container, Windbreak, Reclamation Size/Shape Growth Rate: Fast Tree Shape: Round Plant Image Canopy Symmetry: Irregular Canopy Density: Medium Canopy Texture: Fine Height at Maturity: 3 to 5 m Spread at Maturity: 1.5 to 3 meters Time to Ultimate Height: 5 to 10 Years Caesalpinia pulcherrima (Dwarf Poinciana) Botanical Description Foliage Leaf Arrangement: Opposite Leaf Venation: Pinnate Leaf Persistance: Evergreen Leaf Type: Bipinnately compound Leaf Blade: Less than 5 Leaf Shape: Oblong Leaf Margins: Entire Leaf Textures: Rough Leaf Scent: No Fragance Color(growing season): Green Color(changing season): Green Flower Image Flower Flower Showiness: True Flower Size Range: 3 - 7 Flower Type: Raceme Flower Sexuality: Monoecious (Bisexual) Flower Scent: No Fragance Flower Color: Yellow Seasons: Year Round Trunk Trunk Susceptibility to Breakage: Suspected to breakage Number of Trunks: Multi-Trunked,