The Heroic Age of Geometry*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson 3: Rectangles Inscribed in Circles

NYS COMMON CORE MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM Lesson 3 M5 GEOMETRY Lesson 3: Rectangles Inscribed in Circles Student Outcomes . Inscribe a rectangle in a circle. Understand the symmetries of inscribed rectangles across a diameter. Lesson Notes Have students use a compass and straightedge to locate the center of the circle provided. If necessary, remind students of their work in Module 1 on constructing a perpendicular to a segment and of their work in Lesson 1 in this module on Thales’ theorem. Standards addressed with this lesson are G-C.A.2 and G-C.A.3. Students should be made aware that figures are not drawn to scale. Classwork Scaffolding: Opening Exercise (9 minutes) Display steps to construct a perpendicular line at a point. Students follow the steps provided and use a compass and straightedge to find the center of a circle. This exercise reminds students about constructions previously . Draw a segment through the studied that are needed in this lesson and later in this module. point, and, using a compass, mark a point equidistant on Opening Exercise each side of the point. Using only a compass and straightedge, find the location of the center of the circle below. Label the endpoints of the Follow the steps provided. segment 퐴 and 퐵. Draw chord 푨푩̅̅̅̅. Draw circle 퐴 with center 퐴 . Construct a chord perpendicular to 푨푩̅̅̅̅ at and radius ̅퐴퐵̅̅̅. endpoint 푩. Draw circle 퐵 with center 퐵 . Mark the point of intersection of the perpendicular chord and the circle as point and radius ̅퐵퐴̅̅̅. 푪. Label the points of intersection . -

Squaring the Circle a Case Study in the History of Mathematics the Problem

Squaring the Circle A Case Study in the History of Mathematics The Problem Using only a compass and straightedge, construct for any given circle, a square with the same area as the circle. The general problem of constructing a square with the same area as a given figure is known as the Quadrature of that figure. So, we seek a quadrature of the circle. The Answer It has been known since 1822 that the quadrature of a circle with straightedge and compass is impossible. Notes: First of all we are not saying that a square of equal area does not exist. If the circle has area A, then a square with side √A clearly has the same area. Secondly, we are not saying that a quadrature of a circle is impossible, since it is possible, but not under the restriction of using only a straightedge and compass. Precursors It has been written, in many places, that the quadrature problem appears in one of the earliest extant mathematical sources, the Rhind Papyrus (~ 1650 B.C.). This is not really an accurate statement. If one means by the “quadrature of the circle” simply a quadrature by any means, then one is just asking for the determination of the area of a circle. This problem does appear in the Rhind Papyrus, but I consider it as just a precursor to the construction problem we are examining. The Rhind Papyrus The papyrus was found in Thebes (Luxor) in the ruins of a small building near the Ramesseum.1 It was purchased in 1858 in Egypt by the Scottish Egyptologist A. -

P. 1 Math 490 Notes 7 Zero Dimensional Spaces for (SΩ,Τo)

p. 1 Math 490 Notes 7 Zero Dimensional Spaces For (SΩ, τo), discussed in our last set of notes, we can describe a basis B for τo as follows: B = {[λ, λ] ¯ λ is a non-limit ordinal } ∪ {[µ + 1, λ] ¯ λ is a limit ordinal and µ < λ}. ¯ ¯ The sets in B are τo-open, since they form a basis for the order topology, but they are also closed by the previous Prop N7.1 from our last set of notes. Sets which are simultaneously open and closed relative to the same topology are called clopen sets. A topology with a basis of clopen sets is defined to be zero-dimensional. As we have just discussed, (SΩ, τ0) is zero-dimensional, as are the discrete and indiscrete topologies on any set. It can also be shown that the Sorgenfrey line (R, τs) is zero-dimensional. Recall that a basis for τs is B = {[a, b) ¯ a, b ∈R and a < b}. It is easy to show that each set [a, b) is clopen relative to τs: ¯ each [a, b) itself is τs-open by definition of τs, and the complement of [a, b)is(−∞,a)∪[b, ∞), which can be written as [ ¡[a − n, a) ∪ [b, b + n)¢, and is therefore open. n∈N Closures and Interiors of Sets As you may know from studying analysis, subsets are frequently neither open nor closed. However, for any subset A in a topological space, there is a certain closed set A and a certain open set Ao associated with A in a natural way: Clτ A = A = \{B ¯ B is closed and A ⊆ B} (Closure of A) ¯ o Iτ A = A = [{U ¯ U is open and U ⊆ A}. -

Molecular Symmetry

Molecular Symmetry Symmetry helps us understand molecular structure, some chemical properties, and characteristics of physical properties (spectroscopy) – used with group theory to predict vibrational spectra for the identification of molecular shape, and as a tool for understanding electronic structure and bonding. Symmetrical : implies the species possesses a number of indistinguishable configurations. 1 Group Theory : mathematical treatment of symmetry. symmetry operation – an operation performed on an object which leaves it in a configuration that is indistinguishable from, and superimposable on, the original configuration. symmetry elements – the points, lines, or planes to which a symmetry operation is carried out. Element Operation Symbol Identity Identity E Symmetry plane Reflection in the plane σ Inversion center Inversion of a point x,y,z to -x,-y,-z i Proper axis Rotation by (360/n)° Cn 1. Rotation by (360/n)° Improper axis S 2. Reflection in plane perpendicular to rotation axis n Proper axes of rotation (C n) Rotation with respect to a line (axis of rotation). •Cn is a rotation of (360/n)°. •C2 = 180° rotation, C 3 = 120° rotation, C 4 = 90° rotation, C 5 = 72° rotation, C 6 = 60° rotation… •Each rotation brings you to an indistinguishable state from the original. However, rotation by 90° about the same axis does not give back the identical molecule. XeF 4 is square planar. Therefore H 2O does NOT possess It has four different C 2 axes. a C 4 symmetry axis. A C 4 axis out of the page is called the principle axis because it has the largest n . By convention, the principle axis is in the z-direction 2 3 Reflection through a planes of symmetry (mirror plane) If reflection of all parts of a molecule through a plane produced an indistinguishable configuration, the symmetry element is called a mirror plane or plane of symmetry . -

History of Mathematics

Georgia Department of Education History of Mathematics K-12 Mathematics Introduction The Georgia Mathematics Curriculum focuses on actively engaging the students in the development of mathematical understanding by using manipulatives and a variety of representations, working independently and cooperatively to solve problems, estimating and computing efficiently, and conducting investigations and recording findings. There is a shift towards applying mathematical concepts and skills in the context of authentic problems and for the student to understand concepts rather than merely follow a sequence of procedures. In mathematics classrooms, students will learn to think critically in a mathematical way with an understanding that there are many different ways to a solution and sometimes more than one right answer in applied mathematics. Mathematics is the economy of information. The central idea of all mathematics is to discover how knowing some things well, via reasoning, permit students to know much else—without having to commit the information to memory as a separate fact. It is the reasoned, logical connections that make mathematics coherent. The implementation of the Georgia Standards of Excellence in Mathematics places a greater emphasis on sense making, problem solving, reasoning, representation, connections, and communication. History of Mathematics History of Mathematics is a one-semester elective course option for students who have completed AP Calculus or are taking AP Calculus concurrently. It traces the development of major branches of mathematics throughout history, specifically algebra, geometry, number theory, and methods of proofs, how that development was influenced by the needs of various cultures, and how the mathematics in turn influenced culture. The course extends the numbers and counting, algebra, geometry, and data analysis and probability strands from previous courses, and includes a new history strand. -

Chapter 5 Dimensional Analysis and Similarity

Chapter 5 Dimensional Analysis and Similarity Motivation. In this chapter we discuss the planning, presentation, and interpretation of experimental data. We shall try to convince you that such data are best presented in dimensionless form. Experiments which might result in tables of output, or even mul- tiple volumes of tables, might be reduced to a single set of curves—or even a single curve—when suitably nondimensionalized. The technique for doing this is dimensional analysis. Chapter 3 presented gross control-volume balances of mass, momentum, and en- ergy which led to estimates of global parameters: mass flow, force, torque, total heat transfer. Chapter 4 presented infinitesimal balances which led to the basic partial dif- ferential equations of fluid flow and some particular solutions. These two chapters cov- ered analytical techniques, which are limited to fairly simple geometries and well- defined boundary conditions. Probably one-third of fluid-flow problems can be attacked in this analytical or theoretical manner. The other two-thirds of all fluid problems are too complex, both geometrically and physically, to be solved analytically. They must be tested by experiment. Their behav- ior is reported as experimental data. Such data are much more useful if they are ex- pressed in compact, economic form. Graphs are especially useful, since tabulated data cannot be absorbed, nor can the trends and rates of change be observed, by most en- gineering eyes. These are the motivations for dimensional analysis. The technique is traditional in fluid mechanics and is useful in all engineering and physical sciences, with notable uses also seen in the biological and social sciences. -

And Are Congruent Chords, So the Corresponding Arcs RS and ST Are Congruent

9-3 Arcs and Chords ALGEBRA Find the value of x. 3. SOLUTION: 1. In the same circle or in congruent circles, two minor SOLUTION: arcs are congruent if and only if their corresponding Arc ST is a minor arc, so m(arc ST) is equal to the chords are congruent. Since m(arc AB) = m(arc CD) measure of its related central angle or 93. = 127, arc AB arc CD and . and are congruent chords, so the corresponding arcs RS and ST are congruent. m(arc RS) = m(arc ST) and by substitution, x = 93. ANSWER: 93 ANSWER: 3 In , JK = 10 and . Find each measure. Round to the nearest hundredth. 2. SOLUTION: Since HG = 4 and FG = 4, and are 4. congruent chords and the corresponding arcs HG and FG are congruent. SOLUTION: m(arc HG) = m(arc FG) = x Radius is perpendicular to chord . So, by Arc HG, arc GF, and arc FH are adjacent arcs that Theorem 10.3, bisects arc JKL. Therefore, m(arc form the circle, so the sum of their measures is 360. JL) = m(arc LK). By substitution, m(arc JL) = or 67. ANSWER: 67 ANSWER: 70 eSolutions Manual - Powered by Cognero Page 1 9-3 Arcs and Chords 5. PQ ALGEBRA Find the value of x. SOLUTION: Draw radius and create right triangle PJQ. PM = 6 and since all radii of a circle are congruent, PJ = 6. Since the radius is perpendicular to , bisects by Theorem 10.3. So, JQ = (10) or 5. 7. Use the Pythagorean Theorem to find PQ. -

High School Geometry Model Curriculum Math.Pdf

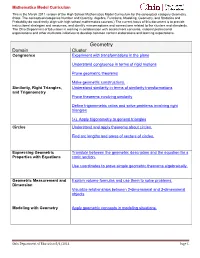

Mathematics Model Curriculum This is the March 2011 version of the High School Mathematics Model Curriculum for the conceptual category Geometry. (Note: The conceptual categories Number and Quantity, Algebra, Functions, Modeling, Geometry, and Statistics and Probability do not directly align with high school mathematics courses.) The current focus of this document is to provide instructional strategies and resources, and identify misconceptions and connections related to the clusters and standards. The Ohio Department of Education is working in collaboration with assessment consortia, national professional organizations and other multistate initiatives to develop common content elaborations and learning expectations. Geometry Domain Cluster Congruence Experiment with transformations in the plane Understand congruence in terms of rigid motions Prove geometric theorems Make geometric constructions. Similarity, Right Triangles, Understand similarity in terms of similarity transformations and Trigonometry Prove theorems involving similarity Define trigonometric ratios and solve problems involving right triangles (+) Apply trigonometry to general triangles Circles Understand and apply theorems about circles. Find arc lengths and areas of sectors of circles. Expressing Geometric Translate between the geometric description and the equation for a Properties with Equations conic section. Use coordinates to prove simple geometric theorems algebraically. Geometric Measurement and Explain volume formulas and use them to solve problems. Dimension -

Descriptive Geometry Section 10.1 Basic Descriptive Geometry and Board Drafting Section 10.2 Solving Descriptive Geometry Problems with CAD

10 Descriptive Geometry Section 10.1 Basic Descriptive Geometry and Board Drafting Section 10.2 Solving Descriptive Geometry Problems with CAD Chapter Objectives • Locate points in three-dimensional (3D) space. • Identify and describe the three basic types of lines. • Identify and describe the three basic types of planes. • Solve descriptive geometry problems using board-drafting techniques. • Create points, lines, planes, and solids in 3D space using CAD. • Solve descriptive geometry problems using CAD. Plane Spoken Rutan’s unconventional 202 Boomerang aircraft has an asymmetrical design, with one engine on the fuselage and another mounted on a pod. What special allowances would need to be made for such a design? 328 Drafting Career Burt Rutan, Aeronautical Engineer Effi cient travel through space has become an ambi- tion of aeronautical engineer, Burt Rutan. “I want to go high,” he says, “because that’s where the view is.” His unconventional designs have included every- thing from crafts that can enter space twice within a two week period, to planes than can circle the Earth without stopping to refuel. Designed by Rutan and built at his company, Scaled Composites LLC, the 202 Boomerang aircraft is named for its forward-swept asymmetrical wing. The design allows the Boomerang to fl y faster and farther than conventional twin-engine aircraft, hav- ing corrected aerodynamic mistakes made previously in twin-engine design. It is hailed as one of the most beautiful aircraft ever built. Academic Skills and Abilities • Algebra, geometry, calculus • Biology, chemistry, physics • English • Social studies • Humanities • Computer use Career Pathways Engineers should be creative, inquisitive, ana- lytical, detail oriented, and able to work as part of a team and to communicate well. -

Tetrahedra and Relative Directions in Space Using 2 and 3-Space Simplexes for 3-Space Localization

Tetrahedra and Relative Directions in Space Using 2 and 3-Space Simplexes for 3-Space Localization Kevin T. Acres and Jan C. Barca Monash Swarm Robotics Laboratory Faculty of Information Technology Monash University, Victoria, Australia Abstract This research presents a novel method of determining relative bearing and elevation measurements, to a remote signal, that is suitable for implementation on small embedded systems – potentially in a GPS denied environment. This is an important, currently open, problem in a number of areas, particularly in the field of swarm robotics, where rapid updates of positional information are of great importance. We achieve our solution by means of a tetrahedral phased array of receivers at which we measure the phase difference, or time difference of arrival, of the signal. We then perform an elegant and novel, albeit simple, series of direct calculations, on this information, in order to derive the relative bearing and elevation to the signal. This solution opens up a number of applications where rapidly updated and accurate directional awareness in 3-space is of importance and where the available processing power is limited by energy or CPU constraints. 1. Introduction Motivated, in part, by the currently open, and important, problem of GPS free 3D localisation, or pose recognition, in swarm robotics as mentioned in (Cognetti, M. et al., 2012; Spears, W. M. et al. 2007; Navarro-serment, L. E. et al.1999; Pugh, J. et al. 2009), we derive a method that provides relative elevation and bearing information to a remote signal. An efficient solution to this problem opens up a number of significant applications, including such implementations as space based X/Gamma ray source identification, airfield based aircraft location, submerged black box location, formation control in aerial swarm robotics, aircraft based anti-collision aids and spherical sonar systems. -

1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Lines, and Planes

Understanding Points, 1-11-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Lines, and Planes Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Objectives Identify, name, and draw points, lines, segments, rays, and planes. Apply basic facts about points, lines, and planes. Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Vocabulary undefined term point line plane collinear coplanar segment endpoint ray opposite rays postulate Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes The most basic figures in geometry are undefined terms, which cannot be defined by using other figures. The undefined terms point, line, and plane are the building blocks of geometry. Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Points that lie on the same line are collinear. K, L, and M are collinear. K, L, and N are noncollinear. Points that lie on the same plane are coplanar. Otherwise they are noncoplanar. K L M N Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Example 1: Naming Points, Lines, and Planes A. Name four coplanar points. A, B, C, D B. Name three lines. Possible answer: AE, BE, CE Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Example 2: Drawing Segments and Rays Draw and label each of the following. A. a segment with endpoints M and N. N M B. opposite rays with a common endpoint T. T Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Check It Out! Example 2 Draw and label a ray with endpoint M that contains N. -

Can One Design a Geometry Engine? on the (Un) Decidability of Affine

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Can one design a geometry engine? On the (un)decidability of certain affine Euclidean geometries Johann A. Makowsky Received: June 4, 2018/ Accepted: date Abstract We survey the status of decidabilty of the consequence relation in various ax- iomatizations of Euclidean geometry. We draw attention to a widely overlooked result by Martin Ziegler from 1980, which proves Tarski’s conjecture on the undecidability of finitely axiomatizable theories of fields. We elaborate on how to use Ziegler’s theorem to show that the consequence relations for the first order theory of the Hilbert plane and the Euclidean plane are undecidable. As new results we add: (A) The first order consequence relations for Wu’s orthogonal and metric geometries (Wen- Ts¨un Wu, 1984), and for the axiomatization of Origami geometry (J. Justin 1986, H. Huzita 1991) are undecidable. It was already known that the universal theory of Hilbert planes and Wu’s orthogonal geom- etry is decidable. We show here using elementary model theoretic tools that (B) the universal first order consequences of any geometric theory T of Pappian planes which is consistent with the analytic geometry of the reals is decidable. The techniques used were all known to experts in mathematical logic and geometry in the past but no detailed proofs are easily accessible for practitioners of symbolic computation or automated theorem proving. Keywords Euclidean Geometry · Automated Theorem Proving · Undecidability arXiv:1712.07474v3 [cs.SC] 1 Jun 2018 J.A. Makowsky Faculty of Computer Science, Technion–Israel Institute of Technology, Haifa, Israel E-mail: [email protected] 2 J.A.