Proceedings of an International Year of Mountains: Part 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

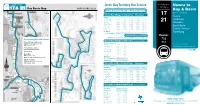

Jervis Bay Territory Bus Service Look for Bus Nowra to Numbers 17 & 21 Bus Route Map NOWRA COACHES Pty

LOOK FOR BUS Jervis Bay Territory Bus Service Look for bus Nowra to numbers 17 & 21 Bus Route Map NOWRA COACHES Pty. Ltd Transport initiative supplied by the Commonwealth of Australia and serviced by Nowra Coaches Bay & Basin Nowra Coaches Pty Ltd - Phone 4423 5244 Buses Servicing Wreck Bay Village to Vincentia – (Weekdays) 17 Departs Nowra Wreck Bay Village 6.25am 9.10am 11.10am 12.45pm 2.17pm Huskisson Summercloud Bay 6.30am 9.15am 11.15am 12.48pm 2.22pm 21 Green Patch 6.40am 9.25am 11.25am 12.58pm 2.32pm Vincentia Jervis Bay Village 6.47am 9.32am 11.32am 1.05pm 2.39pm HMAS Creswell 6.50am 9.35am 11.35am 1.08pm 2.42pm Bay & Basin Visitors Centre 6.55am 9.42am 11.41am 1.13pm 2.48pm Vincentia 7.08am 9.53am 11.51am 1.23pm 2.58pm Central Avenue Bus Departs Tomerong To Nowra (Via Huskisson) 7.10am 9.55am – 1.25pm** 3.00pm **Services Sanctuary Point, St. Georges Basin & Basin View only. Routes (Via Bay & Basin) – – 11.53am – 3.30pm Connecting Bus Operators 732 Wreck Bay Village to Vincentia – Saturday & Sunday Kennedy’s Bus and Coach Departs (Via Bay & Basin) 733 www.kennedystours.com.au See back cover for Tel: 1300 133 477 Wreck Bay Village 9.08am 1.20pm Summercloud Bay 9.13am 1.25pm detailed route descriptions Premier Motor Service Green Patch 9.23am 1.35pm www.premierms.com.au Jervis Bay Village 9.30am 1.42pm Price 50c Tel: 13 34 10 HMAS Creswell 9.33am 1.45pm Visitors Centre 9.38am 1.48pm Shoal Bus Tel: 02 4423 2122 Vincentia 9.48am 1.58pm Email: [email protected] Bus Departs To Nowra (Via Huskisson) 9.50am – Stuarts Coaches (Via -

Booderee National Park Management Plan 2015-2025

(THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY BLANK – INSIDE FRONT COVER) Booderee National Park MANAGEMENT PLAN 2015- 2025 Management Plan 2015-2025 3 © Director of National Parks 2015 ISBN: 978-0-9807460-8-2 (Print) ISBN: 978-0-9807460-4-4 (Online) This plan is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Director of National Parks. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Director of National Parks GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 This management plan sets out how it is proposed the park will be managed for the next ten years. A copy of this plan is available online at: environment.gov.au/topics/national-parks/parks-australia/publications. Photography: June Andersen, Jon Harris, Michael Nelson Front cover: Ngudjung Mothers by Ms V. E. Brown SNR © Ngudjung is the story for my painting. “It's about Women's Lore; it's about the connection of all things. It's about the seven sister dreaming, that is a story that governs our land and our universal connection to the dreaming. It is also about the connection to the ocean where our dreaming stories that come from the ocean life that feeds us, teaches us about survival, amongst the sea life. It is stories of mammals, whales and dolphins that hold sacred language codes to the universe. It is about our existence from the first sunrise to present day. We are caretakers of our mother, the land. It is in balance with the universe to maintain peace and harmony. -

Exclusive PREVIEW of Vivid Sydney 2018 Where to Eat, Shop, Stay And

LOVE EVERY SECOND OF SYDNEY & NSW IN WINTER 25 May – 16 June 2018 VIVID SYDNEY SYDNEY NEW SOUTH WALES exclusive Where to essential short PREVIEW of vivid eat, shop, stay breaks & long sydney 2018 and play road trips VIVID SYDNEY VIVID – WHAT’S ON 03 What to expect from Vivid Light, Music and Ideas Vivid SYDNEY celebrates VIVID LIGHT WALK Lights on! A guide to the 04 amazing Vivid Light installations VIVID PRECINCTS Find out where to see 10 years of creativity 08 the city light up VIVID MUSIC Get into 23 days 25 May - 16 June 2018 10 of music discovery VIVID IDEAS Hear from global Game 13 Changers & Creative Catalysts GETTING AROUND Plan your journey using public 16 transport during Vivid Sydney HELP FROM OUR FRIENDS Thanks to our partners, 17 collaborators and supporters VIVID MAP Use this map to plan your 20 Vivid Sydney experience SYDNEY BEYOND VIVID Your guide to exploring 21 Sydney and New South Wales SYDNEY FOOD & WINE Foodie hotspots, new bars 22 and tours EXPLORE SYDNEY Where to stay and shop 24 and what to see THE GREAT OUTDOORS There is so much more to do, see and love at vivid sydney in 2018. Your guide to walks, the 25 harbour & high-rise adventures Start planning your experience now. IT’S ON! IN SYDNEY 26 Unmissable sporting events, theatre, musicals and exhibitions VIVID SYDNEY SYDNEY IN WINTER EXPLORE NSW At 6pm on 25 May Vivid Sydney 2018 While you’re here for Vivid Sydney, stay The most geographically diverse State in switches on with the Lighting of the Sails a while longer to explore the vibrancy Australia offers a little bit of everything new south wales of the Sydney Opera House and all light of Sydney in Winter. -

Blundells Flat Area ACT: Management of Natural and Cultural Heritage Values

BBlluunnddeellllss Fllaatt arreeaa AACCTT:: MMaannaaggeemmeenntt off NNaattuurraall anndd Cuullttuurraall Heerriittaaggee Vaalluueess Background Study for the Friends of ACT Arboreta MMMaaarrrkkk BBBuuutttzzz Blundells Flat area ACT: Management of Natural and Cultural Heritage Values Background Study for the Friends of ACT Arboreta Mark Butz © Mark Butz 2004 Cover colour photographs, inside cover photograph and sketch maps © Mark Butz Cover photograph of John Blundell provided by Canberra & District Historical Society This document may be cited as: Butz, Mark 2004. Blundells Flat area, ACT: Management of natural and cultural heritage values - Background study for the Friends of ACT Arboreta. Friends of ACT Arboreta c/- PO Box 7418 FISHER ACT 2611 Tony Fearnside Kim Wells [email protected] [email protected] Phone 02-6288-7656 Phone 02-6251-8303 Fax 02-6288-0442 Fax 02-6251-8308 The views expressed in this report, along with errors of omission or commission, are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Friends of ACT Arboreta or other sources cited. The author welcomes correction of inaccurate or inappropriate statements or citations in this report, and additional information or suggested sources. Mark Butz Futures by Design ™ PO Box 128 JAMISON CENTRE ACT 2614 [email protected] Mob. 0418-417-635 Fax 02-6251-2173 Abbreviations ACT Australian Capital Territory ACTEW ACTEW Corporation (ACT Electricity & Water); ActewAGL ACTPLA ACT Planning & Land Authority ANBG Australian National Botanic Gardens ANU (SRES) Australian National University (School of Resources, Environment & Society) asl above sea level [elevation] c. about (circa) CDHS Canberra & District Historical Society Co. County – plural Cos. COG Canberra Ornithologists Group CSIRO Commonwealth Scientific & Industrial Research Organisation E. -

Submission on Murrah Flora Reserves Draft Working Plan Thank You for This Opportunity to Comment on the State Forest Murrah Flora Reserves

31-Jan-18 Submission on Murrah Flora Reserves Draft Working Plan Thank you for this opportunity to comment on the State Forest Murrah Flora Reserves. We start by recognising OEH staff, Aboriginal and other conservationists whose evidence made saving our South Coast Koalas and ‘overarching values of the reserves’ overwhelmingly inevitable. NPWS managing one landscape under these two NSW Acts (Forestry & Parks) is not practical long-term. My management consultancy experience is from Industry, Government, National Parks Association (NSW) & Gulaga National Park Board (2007-2017). Projects include Unspoilt South Coast & Alps-to-Coast World Heritage. NSW Ministers said Murrah “PROTECTS SOUTH COAST KOALAS & LOCAL TIMBER INDUSTRY” (MR 1-Mar-16). Environment Minister Speakman told the ABC that flora reserves had the same protection as national parks. But local Liberal Andrew Constance, told media they kept the State Forest tenure “instead of national parks so in the future the operation of harvesting them again could be considered.” (Bega District News 4-Mar-16). Would Industry repay the $2.5M paid-out? How many of 278 jobs quoted depend on native forest sawlogs? We reference* opportunities within the 2017 Murrah Draft Plan, under three recommendations: 1. Add Murrah to existing Aboriginal-owned and NPWS co-managed Biamanga National Park [*P.1] ‘The primary purpose … is to conserve the south coast’s last known koala population and the protection of a natural and cultural landscape incorporating Biamanga and Gulaga national parks, both of which are Aboriginal owned and managed by a majority Aboriginal owner board’. [*P.3] ‘The boards aspire to … the Murrah Flora Reserves ultimately being added to Biamanga NP.’ We understand this NSW Government very nearly declared these Murrah Reserves as National Park! Mean-spirited State Forest tenure prevents Aboriginal Owners adding Murrah to their Biamanga NP Lease. -

NPWS Pocket Guide 3E (South Coast)

SOUTH COAST 60 – South Coast Murramurang National Park. Photo: D Finnegan/OEH South Coast – 61 PARK LOCATIONS 142 140 144 WOLLONGONG 147 132 125 133 157 129 NOWRA 146 151 145 136 135 CANBERRA 156 131 148 ACT 128 153 154 134 137 BATEMANS BAY 139 141 COOMA 150 143 159 127 149 130 158 SYDNEY EDEN 113840 126 NORTH 152 Please note: This map should be used as VIC a basic guide and is not guaranteed to be 155 free from error or omission. 62 – South Coast 125 Barren Grounds Nature Reserve 145 Jerrawangala National Park 126 Ben Boyd National Park 146 Jervis Bay National Park 127 Biamanga National Park 147 Macquarie Pass National Park 128 Bimberamala National Park 148 Meroo National Park 129 Bomaderry Creek Regional Park 149 Mimosa Rocks National Park 130 Bournda National Park 150 Montague Island Nature Reserve 131 Budawang National Park 151 Morton National Park 132 Budderoo National Park 152 Mount Imlay National Park 133 Cambewarra Range Nature Reserve 153 Murramarang Aboriginal Area 134 Clyde River National Park 154 Murramarang National Park 135 Conjola National Park 155 Nadgee Nature Reserve 136 Corramy Regional Park 156 Narrawallee Creek Nature Reserve 137 Cullendulla Creek Nature Reserve 157 Seven Mile Beach National Park 138 Davidson Whaling Station Historic Site 158 South East Forests National Park 139 Deua National Park 159 Wadbilliga National Park 140 Dharawal National Park 141 Eurobodalla National Park 142 Garawarra State Conservation Area 143 Gulaga National Park 144 Illawarra Escarpment State Conservation Area Murramarang National Park. Photo: D Finnegan/OEH South Coast – 63 BARREN GROUNDS BIAMANGA NATIONAL PARK NATURE RESERVE 13,692ha 2,090ha Mumbulla Mountain, at the upper reaches of the Murrah River, is sacred to the Yuin people. -

Broken-Hill-Outback-Guide.Pdf

YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO DESTINATION BROKEN HILL Contents Broken Hill 4 Getting Here & Getting Around 7 History 8 Explore & Discover 16 Arts & Culture 32 Eat & Drink 38 Places to Stay 44 Shopping 54 The Outback 56 Silverton 60 White Cliffs 66 Cameron Corner, Milparinka 72 & Tibooburra Menindee 74 Wilcannia, Tilpa & Louth 78 National Parks 82 Going off the Beaten Track 88 City Map 94 Regional Map 98 Have a safe and happy journey! Your feedback about this guide is encouraged. Every endeavor has been made to ensure that the details appearing in this publication are correct at the time of printing, but we can accept no responsibility for inaccuracies. Photography has been provided by Broken Hill City Council, Broken Heel Festival: 7-9 September 2018 Destination NSW, NSW National Parks & Wildlife, Simon Bayliss and other contributors. This visitor guide has been designed and produced by Pace Advertising Pty. Ltd. ABN 44 005 361 768 P 03 5273 4777, www.pace.com.au, [email protected]. Copyright 2018 Destination Broken Hill. 2 BROKEN HILL & THE OUTBACK GUIDE 2018 3 There is nowhere else quite like Broken Hill, a unique collision of quirky culture with all the hallmarks of a dinky-di town in the Australian outback. A bucket-list destination for any keen BROKEN traveller, Broken Hill is an outback oasis bred by the world’s largest and dominant mining company, BHP (Broken Hill Proprietary), a history HILL Broken Hill is Australia’s first heritage which has very much shaped the town listed city. With buildings like this, it’s today. -

Southern Trails Next Meeting: the December Club Meeting Will Be Held at the Canberra Deakin Football Club at 7:30Pm on Tuesday 9Th February

February 2021 Southern Trails Next Meeting: The December Club Meeting will be held at the Canberra Deakin Football Club at 7:30pm on Tuesday 9th February. (Please see the Club Meetings COVID-19 Safety Plan on pg. 4) As I look to the west.. (Mt Coree) Directory President: General Meetings are held at the Andy Squire ([email protected]) Canberra Deakin Football Club, Grose St, Deakin at 7:30pm on the second Tuesday of each month. Vice President: Lynne Donaldson General meetings are where Club members and visitors can meet and ([email protected]) get information on past and future Club activities in an informal atmosphere. Meetings regularly feature talks from experts on topics Secretary: of interest, and reports on past trips. Visitors can introduce Lisa Tatem themselves, there is a raffle with generous prizes and a coffee break ([email protected]) for catching up with other members. Ideas for guest speakers are welcome, please don’t hesitate to contact Treasurer: the Committee if you know of someone who could make an Jim Anderson interesting and topical presentation. ([email protected]) Many members gather before the meeting to enjoy a meal or a drink at Membership Secretary: the club. Robert Phillips ([email protected]) Publications Events and Trips Coordinator: Website: Information regarding the Club, our activities, sponsors, and Michael Patrick membership is available on our website at www.st4wdc.com.au. ([email protected]) Facebook: the ST4WDC page includes posts regarding Club activities and sponsors and can be found at www.facebook.com/st4wdc/. -

Accessing Country Last Updated: May 2014

Aboriginal Communities Accessing Country Last updated: May 2014 These Fact Sheets are a guide only and are no substitute for legal advice. To request free initial legal advice on an environmental or planning law issue, please visit our website1 or call our Environmental Law Advice Line. Your request will be allocated to one of our solicitors who will call you back, usually within a few days of your call. Sydney: 02 9262 6989 Northern Rivers: 1800 626 239 Rest of NSW: 1800 626 239 EDO NSW has published a book on environmental Law for Aboriginal communities in NSW. For a more comprehensive guide, read Caring for Country: A guide to environmental law for Aboriginal communities in NSW. Overview Aboriginal people need to be able to access lands and waters to continue their traditions. These traditional practices include fishing, hunting, gathering food, camping, gathering firewood, visiting places with cultural significance, caring for country, caring for burial and other sites, and practising culture. Aboriginal people may always attempt to negotiate access, but the landowner may not always agree. The legal rights of Aboriginal people to access land and water depend on the legal status of the land or waterway. Further information about land dealings may be obtained from the EDO’s series of Fact Sheets and from the NSW Aboriginal Land Council. Access to particular types of land General A Local Aboriginal Land Council (LALC) may negotiate an agreement with any land owner or occupier or person in control of land to permit an Aboriginal group or 1 http://www.edonsw.org.au/legal_advice 2 individual ‘to have access to the land for the purpose of hunting, fishing or gathering on the land’.2 If an agreement cannot be reached, the LALC may request that the Land and Environment Court issue a permit to access the land, or a right of way across the land, for the purpose of hunting, or fishing, or gathering traditional foods for domestic purposes.3 The Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) allows for access agreements to be negotiated. -

Alpine Sphagnum Bogs and Associated Fens

Alpine Sphagnum Bogs and Associated Fens A nationally threatened ecological community Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 Policy Statement 3.16 This brochure is designed to assist land managers, owners and occupiers to identify, assess and manage the Alpine Sphagnum Bogs and Associated Fens, an ecological community listed under Australia’s national environment law, the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). The brochure is a companion document to the listing advice which can be found at the Australian Government’s Species Profile and Threats Database (SPRAT). Please go to the Alpine Sphagnum Bogs and Associated Fens ecological community profile in SPRAT, then click on the ‘Details’ link: www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/publiclookupcommunities.pl • The Alpine Sphagnum Bogs and Associated Fens ecological community is found in small pockets in the high country of Tasmania, Victoria, New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory. • The Alpine Sphagnum Bogs and Associated Fens ecological community can usually be defined by the presence or absence of sphagnum moss. • Long term conservation and restoration of this ecological community is essential in order to protect vital inland water resources. • Implementing favourable land use and management practices is encouraged at sites containing this ecological community. Disclaimer The contents of this document have been compiled using a range of source materials. This document is valid as at August 2009. The Commonwealth Government is not liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of or reliance on the contents of the document. © Commonwealth of Australia 2009 This work is copyright. -

The Canberra Firestorm

® HJ[ Jvyvulyz Jv|y{ 977= [opz ~vyr pz jvwÅypno{5 Hwhy{ myvt huÅ |zl hz wlytp{{lk |ukly {ol JvwÅypno{ Hj{ 8@=?3 uv why{ thÅ il ylwyvk|jlk iÅ huÅ wyvjlzz ~p{ov|{ ~yp{{lu wlytpzzpvu myvt {ol [lyyp{vyÅ Yljvykz Vmmpjl3 Jvtt|up{Å huk Pumyhz{y|j{|yl Zly}pjlz3 [lyyp{vyÅ huk T|upjpwhs Zly}pjlz3 HJ[ Nv}lyutlu{3 NWV IvÄ 8<?3 Jhuilyyh Jp{Å HJ[ 9=785 PZIU 7˛@?7:979˛8˛= Pux|pyplz hiv|{ {opz w|ispjh{pvu zov|sk il kpylj{lk {vA HJ[ Thnpz{yh{lz Jv|y{ NWV IvÄ :>7 Ruv~slz Wshjl JHUILYYH HJ[ 9=78 79 =98> ;9:8 jv|y{tj{jvyvulyzGhj{5nv}5h| ~~~5jv|y{z5hj{5nv}5h| Lkp{lk iÅ Joypz Wpypl jvtwyloluzp}l lkp{vyphs zly}pjlz Jv}ly klzpnu iÅ Q|spl Ohtps{vu3 Tpyyhivvrh Thyrl{pun - Klzpnu Kvj|tlu{ klzpnu huk shÅv|{ iÅ Kliipl Wopsspwz3 KW Ws|z Wypu{lk iÅ Uh{pvuhs Jhwp{hs Wypu{pun3 Jhuilyyh JK k|wspjh{pvu iÅ Wshzwylzz W{Å S{k3 Jhuilyyh AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY OFFICE OF THE CORONER 19 December 2006 Mr Simon Corbell MLA Attorney-General Legislative Assembly of the ACT Civic Square London Circuit CANBERRA ACT 2601 Dear Attorney-General In accordance with s. 57 of the ACT Coroners Act 1997, I report to you on the inquests into the deaths of Mrs Dorothy McGrath, Mrs Alison Tener, Mr Peter Brooke and Mr Douglas Fraser and on my inquiry into the fires in the Australian Capital Territory between 8 and 18 January 2003. -

Australian Alps Education Kit – Teacher's Notes

teacher’s notes for THE AUSTRALIAN ALPS The Australian Alps, in all their richness, complexity and power to engage, are presented here as a resource for secondary students and their teachers who are studying... • Aboriginal Studies • Geography • Australian History • Biology • Tourism • Outdoor and Environmental Science ...with resources grouped within a series of facts sheets on soils, climate, vegetation, fauna, fire, Aboriginal people, mining, grazing, water catchment recreation and tourism, conservation. EDUCATION RESOURCE TEACHER’S NOTES 1/7 teacher’s notes This is an education resource catering for the curriculum needs of students at Year 7 through 12, across New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory and Victoria. The following snap- shots show the Australian Alps as an effective focus for study. • The alpine and sub-alpine terrain in Australia is extremely small, unique and highly valued as a water supply as well as for its environmental, cultural, historic and recrea- tional significance. • Most of the Australian Alps lie within national parks with state and federal governments working cooperatively to manage these reserves as one bio-geographical area. • Climate, landforms and soils vary as altitude increases and so create a variety of envi- ronments where different plants grow together in communities. These in turn provide habitats for a wide range of wildlife. Many of these plants and animals are found nowhere else in the world and some are considered threatened or endangered. • The Alps reflect a history of diverse uses and connections including Aboriginal occupation, European exploration, grazing, mining, timber saw milling, water harvesting, conservation, recreation and tourism. Retaining links with this past is an important part of managing the region.