Form and Dysfunction Neil Labute’S the Shape of Things and Jordan Melamed’S Manic by Scott Foundas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Filthy Talk for Troubled Times Scenes of Intolerance by Neil Labute

City Garage presents the West Coast Premiere of Filthy Talk for Troubled Times Scenes of Intolerance by Neil LaBute Directed by Frédérique Michel Production Design by Charles Duncombe January 6 — February 26, 2012 Filthy Talk for Troubled Times Scenes of Intolerance by Neil LaBute Directed by Frédérique Michel Production Design by Charles Duncombe Art Talk text by Charles Duncombe Cast Troy Dunn .................................................................. Man 3 David E. Frank ............................................................ Man 4 Kye Kinder ....................................................... Art Object #1 Dave Mack ................................................................ Man 1 Cynthia Mance ......................................................Waitress 1 Katrina Nelson ......................................................Waitress 2 Heather Leigh Pasternak ..................................... Art Object #3 Vera Petrychenka .............................................. Art Object #2 Kenneth Rudnicki ........................................................ Man 2 Production Staff Set and Lighting Design .............................. Charles Duncombe 1st Assistant Director .........................................Justin Davanzo 2nd Assistant Director ...........................................Yumi Roussin Costume Design ........................................... Josephine Poinsot Sound Design/Publicity Photography .................Paul Rubenstein Light/Sound Operator ......................................Mitchell -

The Shape of Things

The Shape of Things Neil LaBute first made a name for himself as a caustic commentator on male-female relationships in films like In the Company of Men and Your Friends and Neighbors, unsettling little dramas that depicted the little cruelties people visit on each other in living their lives, but dramas, too, that made you think about your actions. After taking a breather with productions like the antic Nurse Betty and the intelligent romance Possession, the director seems to have come back home to his native ground in his new film The Shape of Things (based on his own play). Here again the scale is small and the action limited: two college couples attracting and repelling, fencing and trying to find their way. On a California campus, budding artist Evelyn (Rachel Weisz) takes an interest in nerdish but nice Adam (Paul Rudd) when they meet cute in the local museum, where she is thinking of defacing a statue and he is supposedly guarding same. He is smitten with her, and she reciprocates, taking a special interest in making him over into a more stylish guy, urging him to lose weight and dress more modishly. Her hold on Adam discomfits his friends, fiances Jenny (Gretchen Mol) and Philip (Frederick Weller), whose own relationship hits a rough patch as they become more involved with the "new" Adam and his outspoken girl. Ultimately, Adam realizes that his make over is a sham and that succumbing to the mere "shape of things"--even if it brings him newfound confidence and vigor--can most cruelly disappoint. -

![The Shape of Things / the Shape of Things, Etats-Unis, 2003, 97 Minutes]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1222/the-shape-of-things-the-shape-of-things-etats-unis-2003-97-minutes-1481222.webp)

The Shape of Things / the Shape of Things, Etats-Unis, 2003, 97 Minutes]

Document generated on 09/28/2021 2:59 p.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma The Shape of Things The Shape of Things, Etats-Unis, 2003, 97 minutes Simon Beaulieu Number 226, July–August 2003 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/59153ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Beaulieu, S. (2003). Review of [The Shape of Things / The Shape of Things, Etats-Unis, 2003, 97 minutes]. Séquences, (226), 47–47. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2003 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ CRITIQUES LES FI THE SHAPE OF THINGS thèse artistique, permettant l'émergence d'une prise de conscience Vie de couple, art et vacuité d'un individu (Adam) envers lui-même et par extension d'un indi vidu envers sa société. D'une certaine façon, ce n'est pas tant l'exa- u cynisme et de l'esprit. De l'intelligence et du vitriol. Il n'y a cerbation de cette superficialité sociétaire et culturelle qui est ici Dpas de doute, Neil LaBute revient en force. On savait d'ores soulignée mais bien le pouvoir de séduction de la femme, véritable et déjà que son excursion dans le drame sentimental (Possession) catalyseur de tout le film. -

Casting Announced: Nick Gehlfuss, Shawn Hatosy

CASTING ANNOUNCED: NICK GEHLFUSS, SHAWN HATOSY, AMBER TAMBLYN AND ALICIA WITT IN TONY-NOMINATED BEST PLAY REASONS TO BE PRETTY BY NEIL LABUTE AT GEFFEN PLAYHOUSE DIRECTED BY RANDALL ARNEY JULY 29 TO AUGUST 31 IN THE GIL CATES THEATER LOS ANGELES (June 26, 2014) – Nick Gehlfuss (Shameless, The Newsroom), Shawn Hatosy (Southland, Reckless), Amber Tamblyn (Joan of Arcadia, Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants) and Alicia Witt (Justified, 88 Minutes) are cast in the Geffen Playhouse production of Reasons to Be Pretty, nominated for the Tony Award for Best Play (2009). Helmed by Geffen Playhouse Artistic Director Randall Arney, Reasons to Be Pretty will be performed in the Gil Cates Theater July 29 to August 31 with an opening night of August 6. In Reasons to Be Pretty, LaBute takes on our ongoing fixation with beauty and one man’s inability to say the right thing – ever. When Greg makes an innocuous, off-handed remark about his girlfriend Steph, it triggers a battle by which their relationship will forever be defined. Reasons to Be Pretty continues a series that includes The Shape of Things, Fat Pig (produced at the Geffen in 2006) and Reasons to Be Happy, a sequel in which the same four characters appear and which premiered in June 2013 at MCC Theater. Ben Brantley of The New York Times said of LaBute and Reasons to Be Pretty, “… some of the freshest and most illuminating American dialogue to be heard anywhere these days.” David Rooney in Variety wrote, “This is a thoughtful, mature play … with a warming dose of compassion. -

How to Fight Loneliness the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival How To Fight Loneliness The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. Insights is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2011, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print Insights, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Brian Vaughn as Brad in How To Fight Loneliness, 2017. Contents Information on the Play Synopsis 4 HowCharacters To Fight Loneliness4 About the Playwright 5 Scholarly Articles on the Play How To Fight Loneliness 7 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Synopsis: How To Fight Loneliness Brad and his wife Jodie are anxiously awaiting the arrival of a guest to their home. They are both are in their mid-thirties and have been married for a number of years. They have been through a lot together, especially recently. -

Mary Moody Nurthen Theatre Society

DIRECTOR'SNOTE Here are a handful of questions I've been asking myself - a small exercise to work out my perspectives on nourishment and survival, collaboration and autonomy. Maybe you could read each one to yourself and think of your answer. Maybe speak with the person beside you and see what develops. 0 What did I eat today and where did it all come from originally? 0 Was it affordable? Why? How do I feel about all that? 0 How would I define the modern circle of life? (or: How am I creating food during life? What grows because I die? Am I nutritious?) ° Can a globalized food industry be wholesome? 0 If I purchase a seed, plant it, water it, help it grow to fruit, and then I take a seed from that fruit and I plant it, have I broken the law? 0 Name one law I know about food. 0 How many cooks should be in the kitchen when the kitchen is the theater and the play is about every person trying to live in this world? Mouthfulwas commissioned and first performed in 2015 by Metta Theatre, a London-based theater company. It is a theatrical work by six playwrights hailing from Nigeria, Colombia , the United Kingdom and the United States. The playwrights collaborated with scientists to each investigate an element of our global food crisis and, in doing so, created the personal stories you'll see today here at Mary Moody Northen Theatre , where over 50 of us (students, staff and guests) have been working together in a rehearsal room with these words, these characters and each other, trying to get to the dirty bleed ing heart of it. -

The Shape of Things Free

FREE THE SHAPE OF THINGS PDF Dayle Ann Dodds,Julie Lacome | 32 pages | 07 Mar 1996 | Candlewick Press (MA) | 9781564026989 | English | Cambridge, MA, United States The Shape of Things by Kelly Reemtsen at Albertz Benda - Artland By the end of the play, I felt no sympathy for anyone. Not to be confused with being The Shape of Things in to a character and having a personal dislike of said character. This was more a disinterest in the characters as each was a two-dimensional caricature for different aspects of gender binaries. The Shape of Things comes off less like an engaging, emotionally distant, woman, and more like an unintelligible mashup of every middle- school insecurity a heterosexual man would have about women. Adam is such the model of the. Adam is such the model of the "sensitive" man that I wasn't sure if LaBute even intended for me to ever take the character seriously. I wasn't looking at characters so much as empty models of gender The Shape of Things. Which themselves could be engaging if their representation of those norms wasn't the entirety of their characterization. By the time the twist ending came around, I was so emotionally disinterested in the characters that the shock didn't matter. To LaBute's credit, the twist was unexpected, but it didn't elicit any visceral reaction so much as the kind of kudos I would give a particularly well grown fern. Interesting in execution, but nothing to write home about. What that something is, I'm not sure, The Shape of Things based on the raw material, there is little way to go but up. -

Neil Labute's

NEIL LABUTE’S TO Y TT E R REASONS BEP Photos: Neil A. Ferguson Photos: FEBRUARY 14 23, 2013 YEARS BRITTEN FESTIVAL Opera for the whole family BRITTEN FEBRUARY 7, 9, 15, 17 / 2013 AT THE ROYAL THEATRE TICKETS ON SALE NOW FEBRUARY 14 & 16 / 2013 St. John the Divine Church In collaboration with the Victoria Conservatory of Music featuring the Victoria Children’s Choir Tickets at POV & Conservatory Box Offices 250.385.0222 www.pov.bc.ca MARCH 2 – 10 / 2013 At the Belfry Theatre In collaboration with The Belfry Theatre Tickets at Belfry Theatre Box Office 250.385.6815 www.belfry.bc.ca PUCCINI APRIL 4, 6, 10, 12, 14 / 2013 AT THE ROYAL THEATRE SINGLE TICKETS ON SALE FEBRUARY 18 / 2013 Get the best seats to Tosca before they go on sale to the public By purchasing a combo subscription to Albert Herring & Tosca and Save! Call 250.385.0222 or www.pov.bc.ca for information Reasons to Be Pretty by Neil LaBute CREATIVE TEAM Director Christine Willes* Set Designer Breanna Wise Costume Designer Halley Fulford Lighting Designers Erin Osborne & Michael Whitfield Sound Designer Hayley McCurdy Stage Manager Imogen Wilson Assistant Director Jonathan Maxwell Fight Choreographer Jacques Lemay Projections Coordinator Freya Engman MFA Supervisor Brian Richmond CAST (in alphabetical order) Kent Alex Frankson Greg Robin Gadsby Carly Alberta Holden Rich Blair Moro Steph Reese Nielsen Warehouse Employees Nic Beamish, Kim Black, Sean Brossard, Kapila Rego The outlying suburbs, not very long ago. There will be one 15-minute intermission during the performance. Season -

Press Release- Reasons

Press Release 588 Sutter Street #318 San Francisco, CA 94102 For immediate release 415.677.9596 fax 415.677.9597 February 2013 www.sfplayhouse.org Publicist: Anne Abrams VENUE: 450 Post Street, @ Powell Contact: Susi Damilano [email protected] [email protected] WHAT YOU SAY AND WHAT YOU MEAN COLLIDE reasons to be pretty By Neil LaBute Directed by Susi Damilano March 26-May 11 PRESS OPENING: March 30th, 8pm San Francisco, CA (February 2013) –Smart, funny, edgy yet compassionate, reasons to be pretty by Neil LaBute continues San Francisco Playhouse’s (Bill English, Artistic Director and Susi Damilano, Producing Director) Tenth Season , now in their new venue at 450 Post Street, Directed by Susi Damilano, the ensemble cast features Lauren English*, Craig Marker*, Patrick Russell* and Jennifer Stuckert*. Obsessed. You. Me. America. This bristling comedy confronts our collective obsession with physical beauty. See what happens when Greg, a working-class guy in a long-term relationship, inadvertently remarks to a friend that, compared to a pretty coworker, his girlfriend is "regular." A hopelessly romantic drama about the hopelessness of romance, reasons to be pretty is the final installment (following The Shape of Things and Fat Pig) in Neil LaBute’s critically acclaimed trilogy focusing on America’s obsession with physical appearance. When an off-handed remark disrupts the lives of two young couples, they confront self-deceit, treachery and their own willingness to change. reasons to be pretty has the razor-sharp wit and insight we expect from LaBute, but with an extraordinary new twist – hope! reasons to be pretty premiered Off-Broadway at the Lucille Lortel Theatre and then moved to Broadway where it was nominated for both a Tony Award and Drama Desk Award for Best New Play. -

Neil Labute, the Shape of Things

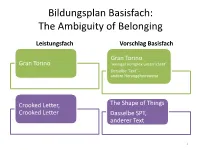

Bildungsplan Basisfach: The Ambiguity of Belonging Leistungsfach Vorschlag Basisfach Gran Torino Gran Torino ‘weniger komplex unterrichtet’ Derselbe ‘Text’ – andere Herangehensweise Crooked Letter, The Shape of Things Crooked Letter Dasselbe SPT, anderer Text 1 Struktur der Präsentation 1. Stück und Autor Handlungszusammenfassung anhand von Screenshots (Einsatz optional) 2. Begründung des Tausches (The Shape statt CLCL) 3. Passung Basisfach 4. Passung SPT 5. Passung Bildungsplan (Leitperspektiven/Kompetenzen) 6. Vertiefungsmöglichkeiten für das Leistungsfach/ als Differenzierung im Basisfach 7. Teaching goals im Literaturunterricht (short drama) 8. Umsetzung im Unterricht (grobe Planung) 2 1 Stück und Autor Neil LaBute, The Shape of Things How far would you go for love? Dies Frage stellt sich Adam als er die attraktive Kunststudentin Evelyn trifft und sich in sie verliebt. Um ihr zu gefallen verändert er sich nach und nach, äußerlich und innerlich. Als er schließlich auch seine Freunde aufgibt, um Evelyn nicht zu verlieren, stellt sich die Frage, ob der Preis, den er bezahlt hat, zu hoch ist. 3 Neil LaBute . Born 1963 in Detroit, . He examines concepts of Michigan love, loneliness, deception . Degrees in Theater and Film and manipulation, identity . One of the most prolific, (unstable, untrue self) controversial and successful . He criticizes mainstream contemporary dramatists culture . Written and directed more . He makes the audience than 20 plays, successfully think about their lives and adapted some of his plays choices into movies, -

Entertainment

ENTERTAINMENTpage 9 Technique • Friday, May 30, 2003 • 9 Find out who’s playing ACC Champs! The ratio is certainly better off-campus; Tech baseball plays 28 innings in one ENTERTAINMENT prove it to yourself by checking out day to capture ACC tournament crown concerts Atlanta has to offer over the for only the fifth time in school history. Technique • Friday, May 30, 2003 next few weeks. Page 11 Page 15 Rudd, Mol, Weisz star in LaBute’s The Shape of Things By Kimberly Rieck ny and Phil’s world. Sports Editor For the play’s original 2001 pro- duction in London, LaBute cast Paul When Neil LaBute was promot- Rudd for the role of Adam, the un- ing his 1997 film In the Company of dergraduate student who falls for Men, he was constantly being asked Evelyn’s manipulations. Rudd had by female journalists if he thought previously been in LaBute’s play women could be as bad as the men Bash, where he portrayed a nice guy in his film. “I answered that, cer- who became a psychotic killer. He’s tainly, I thought women were capa- best known for his starring roles in ble of being as deceitful or doing Clueless, Object of My Affection and such underhanded things to some- most recently his recurring role on one,” says LaBute. “But I imagined the hit series Friends. it would always be a more solitary While LaBute always had Rudd effort, rather than the communal in mind for the role of Adam, he boys-club feeling that In the Com- didn’t have much of a challenge pany of Men filling the rest of had.” the cast. -

Play Synopsis

study guide in the gil cates theater at the geffen playhouse july 29 — august 31, 2014 special thanks to Randall Arney, Amy Levinson, Brian Dunning, Ellen Catania, Jessica Brusilow Rollins, Kristen Smith Eshaya, David Gerhardt, Corky Dominguez and Resa Nikol study guide written and compiled by Jennifer Zakkai This publication is to be used for educational purposes only. REASONS TO BE PRETTY Table of cONTENTS section 1 About this production Artistic director’s comment ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������4 PLAy synopsis �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 5 Artistic biogrAPHIES ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 5 section 2 THEMES & TOPICS looking good............................................................ ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������6 RELAtionship woes ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 8 CONFLICT ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������10 CREAting conflict ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������11