Citizens As Censors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Viswaroopam Telugu Movie Download 720P

Viswaroopam Telugu Movie Download 720p Viswaroopam Telugu Movie Download 720p 1 / 3 2 / 3 They were providing Vishwaroopam movie in 300Mb 700Mb and approx 1.5GB. Go and ... How can we download the movie "Emma" (2020) in HD/720p/1080p?. Jurassic World Fallen Kingdom Telugu Dubbed Movie Jurassic World Fallen ... Download 720p Bluray Jurassic Park II The Lost World (1997) Hindi Movie Full ... Sir, I am unable to download Vishwaroopam 2 movie in hindi. cf" BRRip 1GB .... ... is unaware of his ties to the underworld. However, she finds out, and all hell breaks loose. Watch Vishwaroopam - Tamil Action full movie on Disney+ Hotstar .... SUBSCRIBE for the best Bollywood videos, movies and scenes, all in ONE channel https://goo.gl/lt6aAI Like, Comment and Share with your .... Most Anticipated New Indian Movies and Shows. Real-time popularity on IMDb.. A continuation of Vishwaroopam (2013), it showcases Wisam's relationship with his ... See the top 50 Tamil movies as rated by IMDb users – from evergreen hits to ... (Telugu) Produced by Ghibran Written by Ramajogayya Sastry Performed by .... Vishwaroopam Telugu Movie Download 720p 28 > http://imgfil.com/19cm6t 5fe2a51375 2 Jan 2013 - 2 minVishwaroopam - Telugu Movie .... Running time. 150 minutes. Country, India. Language, Tamil Hindi · Telugu. Vishwaroopam II, or Vishwaroop II, is a 2018 Indian action thriller film made in Tamil and Hindi ... "Vishwaroopam 2 Movie (2018) - Reviews, Cast & Release Date in Pune - BookMyShow". BookMyShow. ... Download as PDF · Printable version .... ... /video/vishwaroopam-2-2018-full-movie-download-hd-720p-tamilrockers-33181 ... -online- vishwaroopam-2-full-movie-torrent-hd-720p-download-free-33356 ... /video/watch-online-jhansi-2018-full-movie-download- hd-720p-telugu-34401 ... -

{PDF EPUB} Still Counting the Dead by Frances Harrison Still Counting the Dead

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Still Counting the Dead by Frances Harrison Still Counting the Dead. Still Counting the Dead: Survivors of Sri Lanka's Hidden War is a book written by the British journalist Frances Harrison, a former BBC correspondent in Sri Lanka and former Amnesty Head of news. The book deals with thousands of Sri Lankan Tamil civilians who were killed, caught in the crossfire during the war. This and the government's strict media blackout would leave the world unaware of their suffering in the final stages of the Sri Lankan Civil War. The books also highlights the failure of the United Nations, whose staff left before the final offensive started. [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] Related Research Articles. The Sri Lankan Civil War was a civil war fought in the island country of Sri Lanka from 1983 to 2009. Beginning on 23 July 1983, there was an intermittent insurgency against the government by the Velupillai Prabhakaran led Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, which fought to create an independent Tamil state called Tamil Eelam in the north and the east of the island due to the continuous discrimination against the Sri Lankan Tamils by the Sinhalese dominated Sri Lankan Government, as well as the 1956, 1958 and 1977 anti-Tamil pogroms and the 1981 burning of the Jaffna Public Library carried out by the majority Sinhalese mobs, in the years following Sri Lanka's independence from Britain in 1948. After a 26-year military campaign, the Sri Lankan military defeated the Tamil Tigers in May 2009, bringing the civil war to an end. -

Download Full Movie Virumandi in 720P

Download Full Movie Virumandi In 720p Download Full Movie Virumandi In 720p 1 / 2 Virumandi 2004 lotus print dvdrip 700mb download tamil movie. Unna vida indha virumaandi songs hd audio. Virumandi video songs andha kandamani song .... Dcyoutube.com is the best download center to download Youtube virumandi film videos at one ... Sandiyar Full Movie in Tamil HD || 2014 movie @Thevan da.. Download Virumandi Video Songs - Mada Vilakke Song Video - Virumandi Tamil Movie Songs Tamil Movie Songs Video Tamil Video in Various 8 HD Video .... Tags: Virumandi Tamil Movie Full Movie download, Virumandi Tamil Movie HD Mobile movie, Virumandi Tamil Movie HD Mp4 movie, Virumandi Tamil Movie .... Virumaandi is a 2004 Indian Tamil language action drama film written, co edited, produced and ... The film begins with Angela Kathamuthu (Rohini), a civil Rights activist and her ..... Create a book · Download as PDF · Printable version .... Movie download Virumandi (2004) free in HD quality 2004.... Virumandi 1080p HD Video Songs Download, Virumandi 1080p HD Video Songs Free Download, Virumandi HD MP4 Free Download.. Keywords : Virumandi HD Video Song Free Download , Virumandi Tamil Movie HD Video Song , Virumandi Tamil Movie 1080p HD Video Song , Virumandi .... Share. Virumandi Telugu Movie Torrent Download ... Share. Telugu Movie Virumandi Free Download ... Share. Virumandi Full Movie Free Download Hd 720p.. Kannathil Muthamittal 2002 full Movie HD Free Download DVDrip. Streaming .... ^VER.,PElicula^ Virumandi Pelicula Completa Online en Español Subtitulada.. The movie is about the love between a Tamil man, Vasu (Kamal Haasan), and a North Indian woman, Sapna (Rati Agnihotri), who are neighbours in Goa.. 3 Jun 2018 ... Power Paandi (2017) Watch Online and Full Movie Download in HD 720p from MovieOrt with fast browsing and high downloading speed on ... -

The Entrenchment of Sinhalese Nationalism in Post-War Sri Lanka by Anne Gaul

An Opportunity Lost The Entrenchment of Sinhalese Nationalism in Post-war Sri Lanka by Anne Gaul Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervised by: Dr. Andrew Shorten Submitted to the University of Limerick, November 2016 Abstract This research studies the trajectory of Sinhalese nationalism during the presidency of Mahinda Rajapaksa from 2005 to 2015. The role of nationalism in the protracted conflict between Sinhalese and Tamils is well understood, but the defeat of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in 2009 has changed the framework within which both Sinhalese and Tamil nationalism operated. With speculations about the future of nationalism abound, this research set out to address the question of how the end of the war has affected Sinhalese nationalism, which remains closely linked to politics in the country. It employs a discourse analytical framework to compare the construction of Sinhalese nationalism in official documents produced by Rajapaksa and his government before and after 2009. A special focus of this research is how through their particular constructions and representations of Sinhalese nationalism these discourses help to reproduce power relations before and after the end of the war. It argues that, despite Rajapaksa’s vociferous proclamations of a ‘new patriotism’ promising a united nation without minorities, he and his government have used the momentum of the defeat of the Tamil Tigers to entrench their position by continuing to mobilise an exclusive nationalism and promoting the revival of a Sinhalese-dominated nation. The analysis of history textbooks, presidential rhetoric and documentary films provides a contemporary empirical account of the discursive construction of the core dimensions of Sinhalese nationalist ideology. -

Assets.Kpmg › Content › Dam › Kpmg › Pdf › 2012 › 05 › Report-2012.Pdf

Digitization of theatr Digital DawnSmar Tablets tphones Online applications The metamorphosis kingSmar Mobile payments or tphones Digital monetizationbegins Smartphones Digital cable FICCI-KPMG es Indian MeNicdia anhed E nconttertainmentent Tablets Social netw Mobile advertisingTablets HighIndus tdefinitionry Report 2012 E-books Tablets Smartphones Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities 3D exhibition Digital cable Portals Home Video Pay TV Portals Online applications Social networkingDigitization of theatres Vernacular content Mobile advertising Mobile payments Console gaming Viral Digitization of theatres Tablets Mobile gaming marketing Growing sequels Digital cable Social networking Niche content Digital Rights Management Digital cable Regionalisation Advergaming DTH Mobile gamingSmartphones High definition Advergaming Mobile payments 3D exhibition Digital cable Smartphones Tablets Home Video Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities Vernacular content Portals Mobile advertising Social networking Mobile advertising Social networking Tablets Digital cable Online applicationsDTH Tablets Growing sequels Micropayment Pay TV Niche content Portals Mobile payments Digital cable Console gaming Digital monetization DigitizationDTH Mobile gaming Smartphones E-books Smartphones Expansion of tier 2 and 3 cities Mobile advertising Mobile gaming Pay TV Digitization of theatres Mobile gamingDTHConsole gaming E-books Mobile advertising RegionalisationTablets Online applications Digital cable E-books Regionalisation Home Video Console gaming Pay TVOnline applications -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

Vishwaroop 2 Movie in Hindi 720Pl

Vishwaroop 2 Movie In Hindi 720pl 1 / 6 2 / 6 Vishwaroop 2 Movie In Hindi 720pl 3 / 6 BHEESHMA Hindi Dubbed Movie Download 480p [471mb] 720p [1. ... Download YTS TORRENT, Watch RACE 3 FREE FILMYWAP,VISHWAROOPAM 2 Direct .... Free Download and watch online Vishwaroopam 2 2018 HDRip 999MB Full Hindi Dubbed Movie Download 720p. Find more Indian, South Hindi Dubbed 720p.. See the top 50 Tamil movies as rated by IMDb users – from evergreen hits to recent chartbusters.. Vishwaroopam II 2018 Full Movie 720p, Dual Audio, Hindi, ... 1. vishwaroopam movie hindi 2. vishwaroopam movie hindi dubbed 480p 3. vishwaroop full movie in hindi download Pandem Kodi 2 is a Tamil dubbed film starring Vishal and Keerthy Suresh in lead roles. ... Sarileru Neekevvaru Movie HD Download 480p 720p 1080p Hy Movie Lovers, do you ... This film is dubbed in Hindi by the same be as Vishwaroopam.. Sir, I am unable to download Vishwaroopam 2 movie in hindi. Please give me a proper link. vishwaroopam movie hindi vishwaroopam movie hindi, vishwaroopam movie hindi dubbed, vishwaroopam movie hindi dubbed 480p, vishwaroop movie hindi, vishwaroop full movie in hindi download, vishwaroopam 2 full movie in hindi download, vishwaroop hindi movie online, vishwaroopam 2 full movie in hindi download filmyzilla, vishwaroop film hindi, vishwaroopam 2 hindi movie download Vishwaroopam 2 Movie Review & Showtimes: Find details of Vishwaroopam 2 along with its . 1:04. ... Download Tamil, Telugu, Hindi, English Movies, HD Video Songs, Audio Songs . ... Vishwaroopam Movie Full Telugu 1080p Vs 720p --- .. Description of the movie: Vishwaroopam 2 (2018) Hindi Line Audio - 720p - HDRip - x264 - ESubs. -

Discourses of Merit and Agrarian Morality in Telugu Popular Cinema

Communication, Culture & Critique ISSN 1753-9129 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Looking Back at the Land: Discourses of Agrarian Morality in Telugu Popular Cinema and Information Technology Labor Padma Chirumamilla School of Information, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA This article takes Anand Pandian’s notion of “agrarian civility” as a lens through which we can begin to understand the discourses of morality, merit, and exclusivity that color both popular Telugu film and Telugu IT workers’ understanding of their technologically enabled work. Popular Telugu film binds visual qualities of the landscape and depictions of heroic technological proficiency to protagonists’ internal dispositions and moralities. I examine the portrayal of the landscape and of technology in two Telugu films: Dhee … kotti chudu,and Nuvvostanante Nenoddantana, in order to more clearly discern the nature of this agrarian civility and—more importantly for thinking about Telugu IT workers— to make explicit its attribution of morality to “merit” and to technological proficiency. Keywords: Information Technology, Morality, Telugu Cinema, Merit, Agrarian Civility. doi:10.1111/cccr.12144 InachasesceneinthepopularTelugufilmDhee … kotti chudu,anameless gangster—having just killed off his rival’s family—is fleeing to Bangalore from Hyderabad, driving along roads surrounded by rocky, barren outcrops, and shriveled patches of trees. The rival’s boss confronts him unexpectedly on the deserted road, quickly and seemingly instantaneously surrounding him with his own men and vehicles, before killing him in retaliation. The film then quickly moves on to its main character, a rather comedic scam artist, and its main spaces, in the city of Hyderabad.1 This particular stretch of barren landscape—scene to the violence that underlies a significant revenge plot woven into the film’s story—is not returned to. -

2 Apar Gupta New Style Complete.P65

INDIAN LAWYERS IN POPULAR HINDI CINEMA 1 TAREEK PAR TAREEK: INDIAN LAWYERS IN POPULAR HINDI CINEMA APAR GUPTA* Few would quarrel with the influence and significance of popular culture on society. However culture is vaporous, hard to capture, harder to gauge. Besides pure democracy, the arts remain one of the most effective and accepted forms of societal indicia. A song, dance or a painting may provide tremendous information on the cultural mores and practices of a society. Hence, in an agrarian community, a song may be a mundane hymn recital, the celebration of a harvest or the mourning of lost lives in a drought. Similarly placed as songs and dance, popular movies serve functions beyond mere satisfaction. A movie can reaffirm old truths and crystallize new beliefs. Hence we do not find it awkward when a movie depicts a crooked politician accepting a bribe or a television anchor disdainfully chasing TRP’s. This happens because we already hold politicians in disrepute, and have recently witnessed sensationalistic news stories which belong in a Terry Prachet book rather than on prime time news. With its power and influence Hindi cinema has often dramatized courtrooms, judges and lawyers. This article argues that these dramatic representations define to some extent an Indian lawyer’s perception in society. To identify the characteristics and the cornerstones of the archetype this article examines popular Bollywood movies which have lawyers as its lead protagonists. The article also seeks solutions to the lowering public confidence in the legal profession keeping in mind the problem of free speech and censorship. -

Vishwaroopam Full Movie in Tamil Hd 1080P

Vishwaroopam Full Movie In Tamil Hd 1080p 1 / 4 Vishwaroopam Full Movie In Tamil Hd 1080p 2 / 4 3 / 4 9 May 2018 - 31 sec02:19. Vishwaroopam II 2015 Tamil Office Trailer New 720P HD Download 00: 46 .. Vishwaroopam 1080p HD Video Songs Download, Vishwaroopam 1080p HD Video Songs Free Download, . Net Tamil MP4 1080p HD Videos Download . Unnai Kannandhu Naan Bluray - Vishwaroopam 1080p HD.mp4 [171.27Mb].. Vishwaroopam (2013) 720p BRRip Tamil Movie Watch Online . Movie Watch Online BRRip 720p , Watch Vishwaroopam Tamil Movie Bluray 720p Online. Online Aalavandhan (2001) HD DVDRip 720p Tamil Full Movie Watch Online.. Tamil Full Movie 2015, Meendum Amman Tamil movies 2015 full movie new . Unnaipol Oruvan (2009) Tamil Movie Online in Ultra HD - Einthusan Kamal.. Vishwaroopam - Brilliance all over the park and Kamal acting is Awesome. contains spoiler . I want to watch this movie but I do not understand Tamil Very well.. 24 Feb 2017 - 143 min - Uploaded by EL ConglomerateVishwaroopam 2013 - Kamal's 5th Directorial Film . Kaun Hai Villain (Villain) 2018 .. 15 May 2013 . Download Tamil, Telugu, Hindi, English Movies, HD Video Songs, Audio Songs . Download Vishwaroopam (2013) Bluray 1080p Tamil Movie.. 17 Jan 2016 - 103 minEnjoy Vishwaroopam Full Movie! Watch HD or Streaming Movie : com/gm95aov .. 1 Jul 2018 - 141 minVishwaroopam. Action Tamil. 2 hr 20 min2013. When Nirupama tries to find a reason to .. See the top 50 Tamil movies as rated by IMDb users from evergreen hits to recent chartbusters. Kamal Haasan in Vishwaroopam (2013) Pooja Kumar at an event for . The movie on a whole is a TERRIFIC VISHWAROOPAM on its own. -

Annual Report

Chartered on 18th December 1983 Sponsor Table : Vijayawada Round Table 68 Table Sponsored : Waltair Round Table 92 & Vizag Vikings Round Table 213 Annual Report at Neptune Hall The Park, Beach Road, Visakhapatnam on Saturday 9th July 2011 7:00 pm 1. Calling the Meeting to Order. 2. Reading of Aims & Objectives. 3. RTI Song 4. AGM Notice 5. Attendance & Apologies 6. Visiting Tablers, Sq. Legs., Ladies, Guests. 7. Appointment of Sergeant at Arms 8. Welcome Address 9. Greetings & Communications Received 10. Confirmation of the 27th AGM 11. Matters arising thereof 12. Annual Report 13. Submission of Accounts 14. Motions / Table Rules (If Any) 15. Presentation of Awards 16. Felicitating the Retiring Tablers 17. Address by Outgoing Chairman 18. Investiture of Jewels 19. Address by Incoming Chairman 20. Office Bearers for the year 2011-12 21. Nomination of Honorary Tablers 22. Presentation of the Budget 23. Appointment of the Bankers & Auditors 24. Resolution authorizing the office bearers to operate the bank accounts 25. Address by the Chief Guest 26. Any Other Matters 27. Sergeant-at-arms 28. Vote of Thanks 29. Closure of Meeting To develop the Fellowship of Young Men through the medium of their Business & Professional Occupation & Community Service activities. To encourage active & responsible Citizenship by cultivating the highest ideals in Business, Professional & Civic Traditions. To promote and further International Understanding, Friendship and Co-operation To promote the extension of the Association. The Round Table India Song was composed in 1970 by Tr. Dipak Shah, a member of Bombay West Round Table No. 6 and adopted as the WOCO Song by World Council at the Hamburg Conference in 1976. -

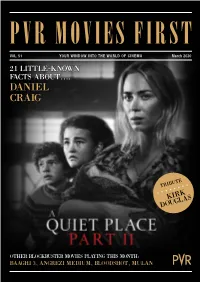

Daniel Craig

PVR MOVIES FIRST VOL. 51 YOUR WINDOW INTO THE WORLD OF CINEMA March 2020 21 LITTLE-KNOWN FACTS AboUt…. DANIEL CRAIG UTE TRIB KIRK DOUGLAS OTHER BLOCKBUSTER MOVIES PLAYING THIS MONTH: BAAGHI 3, ANGREZI MEDIUM, BLOODSHOT, MULAN GREETINGS ear Movie Lovers, 21 amazing facts about Daniel Craig, who celebrates his 52nd birthday this month. Here’s the March issue of Movies First, your exclusive window to the world of cinema. Don’t forget to take a shot at our movie quiz, too. A Quiet Place Part II sees the Abbott family locked in a creepy battle with sound-sensitive forces. Ace action We really hope you enjoy the issue. Wish you a fabulous director Rohit Shetty presents Akshay Kumar in and as month of movie watching. Sooryavanshi. Irrfan makes his much-awaited return as a Regards harried father determined to send his daughter abroad in Angrezi Medium. Join us in paying tribute to the legendary actor Kirk Gautam Dutta Douglas, the last of Hollywood’s golden greats. Learn CEO, PVR Limited USING THE MAGAZINE We hope you’ll find this magazine easy to use, but here’s a handy guide to the icons used throughout anyway. You can tap the page once at any time to access full contents at the top of the page. PLAYPLAY TRAILER BOOKSELECT TICKETS MOVIES PVR MOVIES FIRST PAGE 2 CONTENTS Tap for... Tap for... Movie OF THE MONTH UP CLOSE & PERSONAL Tap for... Tap for... MUST WATCH MASTERS@WORK Tap for... Tap for... RISING Star TRIBUTE TO BOOK TICKETS GO TO PVRCINEMAS.COM OR DOWNLOAD OUR MOBILE APP.