Historical Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collection: DEITRICK, IHLLIAN HENLEY Papers Wake County, Raleigh [1858-185~)

p,C 1487.1-.31 Collection: DEITRICK, IHLLIAN HENLEY Papers Wake County, Raleigh [1858-185~). 1931-1974 Physieal Deseription: 13 linear feet plus 1 reel microfilm: correspondence, photographs, colored slides, magazines, architectural plans, account ledgers business records, personal financial records, etc. Acquisition: ca. 1,659 items donated by William H. Deitrick, 1900 McDonald Lane, Raleigh, July, 1971, with addition of two photocopied letters, 1858 an . 1859 in August 1971. Mr. Deitrick died July 14, 1974, and additional papers were willed to f NC Chapter of the American Institute of Architects. In November, 1974, and July, 1975, these papers were given to the State Archives. In this acquisit are five boxes (P.C. 1487.19-.23) of business correspondence generated durin Mr. Deitrick's association with John A. Park, Jr., an intermediary for busin mergers and sales; these five boxes are RESTRICTED until five years after Mr. Park's death. Description: William Henley Deitrick (1895-1974), son of Toakalito Townes and William Henry Deitrick, born Danville, Virginia; graduate, Wake Forest College, 1916; high school principal (Georgia), 1916-1917; 2nd Lt., U.S. Army, 1917-1919; building contractor, 1919-1922; married Elizabeth Hunter of Raleigh, 1920; student, Columbia University, .1922-1924; practicing architect 19.26-1959; consulting architect, 1959+. Architect, Wake Forest College, 1931-1951; other projects: Western N. C. Sanatorium, N. C. State University (student union), Meredith College (auditorium), Elon College (dormitories and dining hall), Campbell College (dormitory), Shaw University (gymnasium, dormitory, classrooms), St. l1ary's Jr. College (music building), U.N.C. Greensboro.(alumnae house), U.N.C. Chapel Hill (married student nousing), Dorton Arena, Carolina Country Club (Raleigh), Ne,.•s & Observer building,. -

Bring Your Family Back to Cary. We're in the Middle of It All!

Bring Your Family Back To Cary. Shaw Uni- versity North Carolina State University North Carolina Museum of Art Umstead State Park North Carolina Museum of History Artspace PNC Arena The Time Warner Cable Music Pavilion The North Carolina Mu- seum of Natural History Marbles Kids Museum J.C. Raulston Arbore- tum Raleigh Little Theatre Fred G. Bond Metro Park Hemlock Bluffs Nature Preserve Wynton’s World Cooking School USA Baseball Na- tional Training Center The North Carolina Symphony Raleigh Durham International Airport Bond Park North Carolina State Fairgrounds James B. Hunt Jr. Horse Complex Pullen Park Red Hat Amphitheatre Norwell Park Lake Crabtree County Park Cary Downtown Theatre Cary Arts Center Page-Walker Arts & History Center Duke University The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill We’re in the middle of it all! Book your 2018 or 2019 family reunion with us at an incredible rate! Receive 10% off your catered lunch or dinner of 50 guests or more. Enjoy a complimen- tary upgrade to one of our Hospitality suites or a Corner suite, depending on availability. *All discounts are pretax and pre-service charge, subject to availability. Offer is subject to change and valid for family reunions in the year 2018 or 2019. Family reunions require a non-refundable deposit at the time of signature which is applied to the master bill. Contract must be signed within three weeks of receipt to take full advantage of offer. Embassy Suites Raleigh-Durham/Research Triangle | 201 Harrison Oaks Blvd, Cary, NC 27153 2018 www.raleighdurham.embassysuites.com | 919.677.1840 . -

Meredith College U Ndergraduate Catalogue

Meredith College Undergraduate Catalogue College Undergraduate Meredith 2010-11 Raleigh, North Carolina undergraduate catalogue 2010-11 ...that I’m ready to try something new...that I don’t know everything. Yet...in learning by doing—even if I get my hands dirty in the process...that leadership can be taught. And I plan to learn it...that the best colleges are good communities...there’s a big world out there. eady to take my place in it...I believe that a good life starts here. At Meredith...that I’m ready to Itry something newBelieve...that I don’t know everything. Yet...in learning by ...doing—even if I get my hands dirty in the process...that leadership 10-066 Office of Admissions 3800 Hillsborough Street Raleigh, NC 27607-5298 (919) 760-8581 or 1-800-MEREDITH [email protected] www.meredith.edu can be taught. And I plan to learn it...that the best colleges are good communities...there’s a big world out there. And I’m ready to take my place in it...I believe that a good life starts here. At Meredith...that I’m ready to try something new...that I don’t know everything. Yet...in learning by doing—even if I get my hands dirty in the process...that leadership can be taught. And I plan to learn it...that the best colleges are good communities...there’s a big world out there. And I’m ready to take my place in it...I believe that a good life starts here. At ...that leadership can be taught. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form 1

NPS FG--' 10·900 OMS No. 1024-0018 (:>82> EXP·10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS u.e only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory-Nomination Form date entered See Instructions In How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries-complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Early -r«entieth Century Raleigh Neighborhoods andlor common 2. Location street & number See individual district continuation sheets _ not for publication city, town Raleigh _ vicinitY of Congressional District Fourth state North Carolina code 037 county Hake code 183 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use ~dlstrlct _public ----.K occupied _ agriculture _museum _ bulldlng(s) _private J unoccupied _ commercial X park _ structure -'L both ----X work In progress l educational l private residence _site Public Acquisition Accessible _ entertainment _ religious _object _In process ----X yes: restricted _ government _ scientific _ being considered --X yes: unrestricted _ Industrial _ transportation N/A -*no _ military __ other: 4. Owner of Property name See individual dis trict continuation sheets street & number city, town _ vicinitY of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Hake County Register of Deeds street & number Fayetteville Street city, town Raleigh state North Carolina 6. Representation in Existing Surveys NIA title has this property been determined eligible? _ yes XX-- no date _ federal __ state _ county _ local depository for survey records city, town state ·- 7. Description Condition Check one Check one ---K excellent -_ deteriorated ~ unaltered ~ original site --X good __ ruins -.L altered __ moved date _____________ --X fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Description: Between 1906 and 1910 three suburban neighborhoods -- Glenwood, Boylan Heights and Cameron Park -- were platted on the northwest, west and southwest sides of the City of Raleigh (see map). -

A Walking Tour of City Cemetery

Tradition has it that Wm Henry Haywood, Jr., (1801- way was established. Finished in January 1833 it was Geddy Hill (1806-1877) was a prominent Raleigh physi 1846), is buried near his sons, Duncan Cameron and Wm. considered the first attempt at a railroad in N' C The cian and a founder of the Medical Society of North Caro Henry, both killed in the Civil War; but his tombstone railroad was constructed to haul stone from' a local Una. is gone. Haywood was a U. S. Senator. He declined ap quarry to build the present Capitol. Passenger cars were pointment by President Van Buren as Charge d'Affairs placed upon it for the enjoyment of local citizens. 33. Jacob Marling (d. 1833). Artist. Marling painted to Belgium. Tracks ran from the east portico of the Capitol portraits in water color and oils of numerous members to the roek quarry in the eastern portion of the city Mrs. of the General Assembly and other well-known personages 18. Josiah Ogden Watson (1774-1852). Landowner. Polk was principal stockholder and the investment re Known for his landscape paintings, Marling's oil-on-canvas Watson was active in Raleigh civic life, donating money portedly paid over a 300 per cent return. painting of the first N. C. State House hangs in the for the Christ Church tower. His home, "Sharon," belong N. C. Museum of History. ed at one time to Governor Jonathan Worth A WALKING 34. Peace Plot. The stone wall around this plot was 19. Romulus Mitchell Saunders (1791-1867). Lawyer designed with a unique drainage system which prevents and statesman. -

Civil Rights Activism in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina, 1960-1963

SUTTELL, BRIAN WILLIAM, Ph.D. Campus to Counter: Civil Rights Activism in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina, 1960-1963. (2017) Directed by Dr. Charles C. Bolton. 296 pp. This work investigates civil rights activism in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina, in the early 1960s, especially among students at Shaw University, Saint Augustine’s College (Saint Augustine’s University today), and North Carolina College at Durham (North Carolina Central University today). Their significance in challenging traditional practices in regard to race relations has been underrepresented in the historiography of the civil rights movement. Students from these three historically black schools played a crucial role in bringing about the end of segregation in public accommodations and the reduction of discriminatory hiring practices. While student activists often proceeded from campus to the lunch counters to participate in sit-in demonstrations, their actions also represented a counter to businesspersons and politicians who sought to preserve a segregationist view of Tar Heel hospitality. The research presented in this dissertation demonstrates the ways in which ideas of academic freedom gave additional ideological force to the civil rights movement and helped garner support from students and faculty from the “Research Triangle” schools comprised of North Carolina State College (North Carolina State University today), Duke University, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Many students from both the “Protest Triangle” (my term for the activists at the three historically black schools) and “Research Triangle” schools viewed efforts by local and state politicians to thwart student participation in sit-ins and other forms of protest as a restriction of their academic freedom. -

Graduate School Catalogue and Handbook 2016-17 Contents / 1

GRADUATE SCHOOL CATALOGUE AND HANDBOOK 2016-17 CONTENTS / 1 The John E. Weems Graduate School at Meredith College Master of Business Administration Master of Education Master of Arts in Teaching Master of Science in Nutrition Business Foundations Certificate Dietetic Internship Didactic Program in Dietetics Pre-Health Post-Baccalaureate Certificate Paralegal Program Volume 24 2016-17 The John E. Weems Graduate School intends to adhere to the rules, regulations, policies and related statements included herein, but reserves the right to modify, alter or vary all parts of this document with appropriate notice and efforts to communicate these matters. Meredith College does not discriminate in the administration of its educational and admissions policies, scholarship and loan programs, athletic and other school-administered programs or in access to its programs and activities on the basis of race, creed, sexual orientation, national or ethnic origin, gender, age or disability. CONTENTS / 2 Contents INTRODUCTION Overview 3 GRADUATE CATALOGUE Admissions 6 Academic Policies 12 Tuition and Fees 19 GRADUATE PROGRAMS Master of Business Administration 22 Business Foundations Certificate 23 Master of Education 26 Teacher Licensure 26 Master of Arts in Teaching 33 Master of Science in Nutrition 38 Dietetic Internship 43 Didactic Program in Dietetics 45 Pre-Health Post-Baccalaureate Certificate 47 Paralegal Program 48 GRADUATE SCHOOL FACULTY AND STAFF DIRECTORY 51 GRADUATE STUDENT HANDBOOK 54 Graduate Student Activities and Services 54 Campus Policies and Procedures 60 Important Phone Numbers 68 INDEX 69 ACADEMIC CALENDAR 71 CAMPUS MAP 72 OVERVIEW / 3 Overview Values The Meredith College community is dedicated to core values Chartered in 1891, Meredith College has been educating the drawn from Meredith’s mission and heritage, including its South’s – and now, some of the world’s – brightest and most founding as a women’s college by North Carolina Baptists. -

View League Activities As an Investment Bers,” Added Michieka

2010 May the Presorted Standard A PUBLICATION OF THE JUNIOR LEAGUE OF RALEIGH U.S. Postage PAID Raleigh, NC Permit No. 315 DeShelia A. Spann Photograp Spann A. DeShelia hy Cookbook sales are now underway. Order yours today! PhotograPh Provided by tammy Wingo PhotograPhy Our mission May 2010 the Junior League of 2 President’s Message Raleigh is an 5 Member Spotlights organization of women 12 Scene and Heard committed to promoting 15 Shout Outs voluntarism, developing 16 Women in Leadership, Part II the potential of women 18 2010 Showcase of Kitchens and improving 22 Recipe Corner communities through the 30 Meet Your New Neighbors effective action and 35 Best of . leadership of trained volunteers. 711 Hillsborough Street P.O. Box 26821 Raleigh, NC 27611-6821 Phone: 919-787-7480 Voice Mail: 919-787-1103 Fax: 919-787-9615 www.jlraleigh.org Bargain Box Phone: 919-833-7587 President’s Message Membership in the Junior League with volunteers — from the families and means so much to each of us. For some, the children at SAFEchild to the places that League establishes connections with other we all enjoy from historic homes to the women and a new circle of friends. For North Carolina Art Museum. They have . others, the League makes a difference in given us the vision to see opportunities for inc , the community with a greater impact than new fundraisers from A Shopping SPREE! studio we could achieve individually since we are to the Showcase of Kitchens and our new batchelor working together to improve the lives of cookbook. -

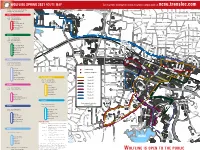

Wolfline Is Open to the Public

WOLFLINE SPRING 2021 ROUTE MAP Get real-time information on bus locations campus-wide at ncsu.transloc.com LITTLE LAKE HILL DR D R WADE R E AVE B R D G P TO A LYON ST E BLUE D D T R E N I N R ER IDGE WADE AVE B Weekday service operates Monday through Friday. LY WAD I U KAR RD E R AVE OOR LEONARD ST R AM Y P I M RAND DR 440 MAYFAIR RD M TO EXIT R Following are time points and major stops: 4 RAMP MAR A I WB D 4 BALLYHASK PL NOS 40 BLUE RIDGE RD TO WADE AVE RAMP EB B GRANT AVE RA E M P J WE STCHAS P M DUPLIN RD R E â (!BLVD A REDBUD LN WB R DR CBC Facilities Svc Ctr CT ROUTE 30 4 BROOKS AVE T WELDON PL (! I WELLS AVE TUS BAEZ ST EX T 7:00 am – 4:30 pm, 9 minute frequency 0 E 4 M MITCHELL ST HORSE LN 4 I 4:30 pm – 7:30 pm, 14 minute frequency HY â â CANTERBURY RD 7:30 pm – 12:00 am, 25 minute frequency PECORA LN RUMINANT LN ü" LN DOGWOOD VE Power Plant !! A RY LN VIEW CT CAMERON Wolf Village IN DR ER PE H Wendel Murphy Center T C OBERRY ST R R Reprod Physiology U O NCSUC Centennial RD ES King Village (Gorman St) H RY M ET TER DA L D Meredith SATULA AVE R Current Dr/Stinson Dr G Biomedical Campus FAIRCLOTH ST O BEAVER DIXIE TRL Main Vet School College BARMETTLER ST Yarbrough Dr/Stinson Dr TRINITY RD IDGE (! R E SONORA ST â T University Club Y C Student Health HLE BLU N A S MA MAYVIEW RD IEW RD DR Y AYV (! DR MOORE WILLIAM B VIEW RD M PHY W CVM Research T (! R P STACY ST U AM M S M R E Terry Medical Center 3 R R EDITH E A IT T D X C S RUFFIN ST N E D N E O L L EG ROSEDALE AVE LI 0 R 4 ST TOWER 4 A T I G ROUTE 40 S FOWLER AVE ST PARKER R â (! -

Historic Architecture Survey for Raleigh Union Station, Phase II - RUS Bus Project Wake County, North Carolina

Historic Architecture Survey for Raleigh Union Station, Phase II - RUS Bus Project Wake County, North Carolina New South Associates, Inc. Historic Architecture Survey for Raleigh Union Station, Phase II – RUS Bus Project Wake County, North Carolina Report submitted to: WSP • 434 Fayetteville Street • Raleigh, North Carolina 27601 Report prepared by: New South Associates • 1006 Yanceyville Street • Greensboro, North Carolina 27405 Mary Beth Reed – Principal Investigator Brittany Hyder – Historian and Co-Author Sherry Teal – Historian and Co-Author July 16, 2020 • Final Report New South Associates Technical Report 4024 HISTORIC ARCHITECTURE SURVEY OF RALEIGH UNION STATION, PHASE II – RUS BUS PROJECT, WAKE COUNTY, NORTH CAROLINA i MANAGEMENT SUMMARY New South Associates, Inc. (New South) completed a historic architecture survey for the proposed Research Triangle Regional Public Transportation (dba GoTriangle) Project in downtown Raleigh, Wake County, North Carolina. The proposed project, termed RUS Bus, would include the construction of a facility on three parcels (totaling approximately 1.72 acres) owned by GoTriangle at 200 South West Street, 206 South West Street, and 210 South West Street. The existing buildings on the parcels would be demolished as part of the project except for the westernmost wall adjacent to the railroad. The prime consultant, WSP, is under contract with GoTriangle. The project is funded by the Federal Transit Authority (FTA) and, therefore, it must comply with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the regulations of Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), as amended. The work adhered to the procedures and policies established by the North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office (HPO) for compliance with Section 106, as specified in 36 Code of Federal Regulation (CFR) 800. -

Download The

Anniversary DEJANEWS Edition A NEWSLETTER PUBLISHED BY THE RALEIGH HISTORIC DEVELOPMENT COMMISSION It has been said that, at its best, preservation engages the past in a 1 conversation with the present over a mutual concern for the future. 1 William J. Murtagh, Keeping Time:The History and Theory of Preservation in America RHDC 50YEARS Celebrating 50 Years of Preserving Raleigh's Future On December 18, RHDC will celebrate our 50th anniversary. In recognition of this milestone, this issue of our newsletter brings together former and present commissioners, staff, and collaborators to reflect upon our past successes, present programs, and future preservation challenges. Linda Edmisten, one of our earliest friends and colleagues, shares her unique perspective on the people and events that shaped the formative years of our commission. Others contribute their insights into our role in the community and the future of preservation. Inside you will also find a preview of upcoming events designed around our anniversary. Since our commission was first established in 1961, Raleigh has experienced a period of unprecedented growth and change, and the opportunities and challenges now facing us as a result of this change are mirrored in similar communities across our country and in much of the world. The demand for more durable and self-reliant local economies, increased energy and infrastructure efficiencies, and expanded affordable housing options are just a few examples of areas in which preservation can and should contribute to our community. We have decided to change our name to the Raleigh Historic Development Commission to better reflect both the importance of our past as well as the promise of a sustainable future. -

Historic Properties Commission 1961 ‐ 1972 Activities and Accomplishments

HISTORIC PROPERTIES COMMISSION 1961 ‐ 1972 ACTIVITIES AND ACCOMPLISHMENTS 1961 – 1967 ▫ Improved City Cemetery and repaired Jacob Johnson monument ▫ Established Capital City Trail in collaboration with Woman’s Club ▫ Published brochures ▫ Laid foundation for interest and education regarding early post office building, Richard B. Haywood House, Mordecai House ▫ Marked historic sites, including Henry Clay Oak and sites in Governorʹs Mansion area June 1967 ▫ Instrumental in passing local legislation granting City of Raleigh’s historic sites commission additional powers ▫ City acquired Mordecai House ▫ Mordecai property turned over to commission to develop and supervise as historic park (first example in state) December 1967 ▫ Partnered with Junior League of Raleigh to publish the book North Carolinaʹs Capital, Raleigh June 1968 ▫ Moved 1842 Anson County kitchen to Mordecai Square, placing it on approximate site of former Mordecai House kitchen August 1968 ▫ City Council approved Mordecai development concept November 1968 ▫ City purchased White‐Holman House property; commission requested to work on solution for preserving house itself; section of property utilized as connector street March 1969 ▫ Supervised excavation of Joel Lane gravesite April 1969 ▫ Collaborated with City to request funds for HUD grant to develop Mordecai Square June 1969 ▫ Lease signed for White‐Holman House September 1969 ▫ Blount Street preservation in full swing May 1970 ▫ Received $29,750 HUD grant for Mordecai development June 1970 ▫ Two ʺPACEʺ students inventoried