Open Jessicaleighbodenthesis Manuscriptt072418.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 S Whitehorse Pike Berlin, NJ 08009

2 S Whitehorse Pike Berlin, NJ 08009 EXCLUSIVE OFFERING www.DoughertyTeam.com ROYAL FARMS | BERLIN, NEW JERSEY TABLE OF CONTENTS Lead Investment Advisors Investment Analysis............04 Derrick Dougherty Tenant Overview.................09 First Vice President Investments Lic: PA RS305854 (215) 531-7026 Location Overview..............12 Scott Woodard Senior Associate Lic: PA RS329242 (215) 531-7058 Mark Krantz Senior Associate Lic: NJ 1863254 | PA RS336064 (215) 531-7056 Steve Garthwaite Senior Associate License: PA RS332182 (215) 531-7025 Pavan Koneru Associate Lic: PA RS350910 (215) 531-7068 Nick Geaneotes Associate Lic: PA RS350646 (215) 531-7071 Colin Reder Associate (215) 531-7057 Broker of Record: Brian Hosey License: NJ 1434917 2 ROYAL FARMS | BERLIN, NEW JERSEY DOUGHERTYTEAM.COM Berlin Circle Plaza Diggerland USA ROYAL FARMS | BERLIN, NEW JERSEY Hwy 73 (34,332 VPD) S. Whitehorse Pike (26,310 VPD) Berlin Farmers Market 2 S. White Horse Pike Berlin, NJ Berlin Cross-Keys Rd (17,414 VPD) 3 ROYAL FARMS | BERLIN, NEW JERSEY DOUGHERTYTEAM.COM ROYAL FARMS | BERLIN, NEW JERSEY 01 INVESTMENT ANALYSIS 4 ROYAL FARMS | BERLIN, NEW JERSEY DOUGHERTYTEAM.COM INVESTMENT OVERVIEW ROYAL FARMS | BERLIN, NEW JERSEY $6,190,000 5.25% $325,000 PRICE CAP RENT LEASE SUMMARY ANNUALIZED OPERATING DATA Tenant Royal Farms Term Dates Base Rent PSF Increase Guarantor Corporate Years 1-10 (Current) 12/5/2019 - 12/31/2029 $325,000 $60.51 - Lease Type NNN Ground Lease Years 11-20 1/1/2030 - 12/31/2039 $357,500 $66.56 10% Gross Leasable Area 5,371 SF Option Terms -

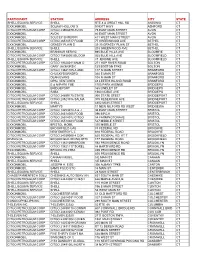

Food Facility Inspection Report

Anne Arundel County Department of Health Food Facility Inspections October 1, 2013 - October 31, 2013 Food Facility Inspections: of the 447 facilities inspected, 41 had critical food safety item violations that were corrected. Food Facility Closings: Oct. 9: Baja Fresh Mexican Grill #145, 2478 A Solomons Island Road, Annapolis, MD 21401 was closed due to the facility operating without hot water available. It was reopened on October 9, 2013. Re-inspection Date Restaurant Name Address City Type Critical Items Needed 10/15/2013 la Madeleine 1861 Annapolis Mall - Store 1464 Annapolis R1 6a Y 10/29/2013 A A Co Detention Center 131 Jennifer Road Annapolis ICI N 10/4/2013 A Caring Hand Adult Day Care 606 Hammonds Lane Upper Level Suites 1-6 Baltimore ICI N 10/29/2013 A Cook's Cafe, LLC 911 Commerce Road Annapolis ICI N 10/24/2013 Adam's Ribs 169 Mayo Road Edgewater IM1 N 10/8/2013 Aloft Hotel BWI 1741 W Nursery Road Linthicum ICI N 10/25/2013 American Legion #226 830 Mayo Road Edgewater ICI N 10/18/2013 American Legion #40 500 5th Avenue Glen Burnie ICI N 10/25/2013 American Legion Post #141 1707 Forest Drive Annapolis IM1 N 10/17/2013 American Legion, Inc. #276 8068 Quarterfield Road Severn IM1 6a N 10/1/2013 Annapolis Area Christian School 109 Burns Crossing Road Severn IM1 N 10/25/2013 Annapolis Organic Market, LLC 25 Market Street Annapolis ICI Y 10/30/2013 Annapolis Organic Market, LLC 25 Market Street Annapolis R Y 10/1/2013 Annapolis Saladworks 1901 Towne Centre Blvd., #130 Annapolis IM2 N 10/16/2013 Annapolis Waterfront Hotel 80 Compromise Street Annapolis IM1 6a Y 10/22/2013 Annapolis Waterfront Hotel 80 Compromise Street Annapolis IM2 6a Y 10/28/2013 Annapolis Waterfront Hotel 80 Compromise Street Annapolis R2 N 10/10/2013 Annapolitan Club, The 81 Franklin Street Annapolis IM1 N 10/8/2013 Annette's Cakery 562 B & A Blvd Severna Park ICI N 10/17/2013 Applebee's Restaurant 2408 Brandermill Blvd Gambrills IM1 N 10/2/2013 Arby's #8009 8103 Ritchie Hwy. -

Challenges Takeaways

Strategic White Paper CHALLENGES The Fuel Price Optimization Solution that is Winning the Battle for Profit and Brand Growth Losing the fuel price/profit margin battle against competitors Losing market share Contents Introduction 2 Growing Industry Leaders Use PriceAdvantage 2 TAKEAWAYS A Closer Look: CEFCO 4 A Closer Look: Royal Farms 4 Integrating automated fuel price optimization and price A Closer Look: Spinx 4 updates to all locations A Closer Look: Valero 4 maximizes profit, positions Optimize or Be Acquired? 5 c-store brands for growth About PriceAdvantage 5 v Introduction In the competitive retail fuel and convenience store markets, the fastest-growing chains are leveraging tools that give them real-time data for setting the “sweet spot” price that brings the customer off the street and to the pump and into the store. They’re also closing the loop with systems that centralize and automate price updates—meaning the optimized price is instantly on display on every sign and pump at every store, with simultaneous updates sent to POS systems and web, smart devices, and social networks. Bundling these price updates means that retail fuel price managers can be confident that the optimal price is in effect without the need for communication to or intervention by dozens, or even hundreds, of store managers. We saved half a penny per gallon driving record fuel sales and profitability in the first year. This was largely due to automation with PriceAdvantage software and Skyline's electronic price signs. — Rob Rinehart, Director of Retail Petroleum, Royal Farms By automating the three major components of the pricing process—collection of key data presented for meaningful analysis, automation of fuel price determination and the integration of technologies to get that optimized price to store and ultimately your customers—fuel retailers and c-stores are literally turning pennies into millions and winning the battle for profit and brand growth. -

Update on Royal Farms Gas Station and Convenience Store Proposed In

SPARKS-GLENCOE COMMUNITY PLANNING COUNCIL Preserving our rural heritage Spring 2015 Newsletter Dear Neighbor, UPDATE ON ROYAL Spring couldn’t get here fast enough this FARMS GAS STATION AND year. And with the thaw we want to bring you CONVENIENCE STORE some updates on what is happening with the Royal Farms proposed new convenience store PROPOSED IN HEREFORD and gas station in Hereford, what the so called In January 2014 a Baltimore County Administrative “rain tax” really signifies, and why the bees are Law Judge granted Royal Farms permission to build a disappearing. The winter melt will also enable gas station and convenience store on Mt. Carmel Road in Hereford, on a site - which is now a corn field - used US Lacrosse to break ground on its new location for the Hereford Fall Festival. Sparks-Glencoe, Graul’s in Loveton. For these stories and more, please Market and other community members (the protestants) read on. appealed that decision to the County’s Board of Appeals. And while you’re thinking about what you Eight days of hearings were held in 2014 and 2015 want to plant in your garden this year, keep in and just concluded. SGCPC members attended every mind that you might be able a get a free new tree day of the hearings, and six members of our Board for your property. The information is inside. testified on various aspects of the case. Mr. Graul, several local residents, and the owner of Michael’s Pizza also testified against the proposal. The Hereford As always, we ask you to also keep us in Community Association voted 38-3, to support it. -

Sheetz Universal Acceptance List

ACCEPTING LOCATIONS ACCEPTANCE WHERE YOU NEED IT — WHEN YOU NEED IT FUEL AC & T Global Pantry Aviation Grow Mark Petro King Bell Gas Halley’s Petro Stop Bigfoot Handy Andy’s PRIDE Break Time Huck’s Pure Capital City ICO Qik N EZ Carousel Ideal Quality Oil Certified Inter City Quik Mart City Garage Johnson & Dixon Robinson Oil Cogos Jr. Food Stores Rotten Robbie Crystal Flash Kenyon Royal Farms Cumberland Farms King Soopers Rutters D & D Oil Koch Rymes 24 Dairy Mart Kramer SC Fuels Depot Krause Smokers Express Drivers Traveler Kroger Sprint Dynamic Mart Kum & Go Stewarts Shops Economy Kwik Pantry Taylor Foods Eddins Walcher Lil Champ TCI Enmark Lucky Stop Thornton Oil ETNA M & H TOTAL Express Stop Macs Stores Town&Country Family Express McClure Oil Trade Mart Farmland MFA Oil Trade Oil Farstad Minit Mart Tripar Oil Fast Stop Mr. Cut Rate US Oil Fauser Oil Multi Serv USCO FFP Murphy Express Valley Dairy Flash Foods NAPA Weigel Store Food Chief Novus Wesco Fuel Mart NU-Way Williams Travel Gas America Oasis Xtra Fuels Giant O’Connor Youngs Git-n-Go OK Petroleum Zip Mart Card acceptance is subject to independent owner/operator participation and subject to change without notice. SERVICE American LubeFast GM Goodwrench Big O Tires (limited participation) Daimler/Chrysler Harmon Glass Diamond/Triumph Netcost Auto Glass Auto Glass Tire Centers Inc Dodge BusinessLink™ Wash Depot (limited participation) WINGFOOT C OMMERCIAL TIRE SYSTEMS , L LC ...and many regional and independent locations nationwide. TM For more information, visit www.WEXinc.com 800-395-0812 WEXU-219 11/12. -

Submitted Vendor Response to an Advertised Solicitation from the West Virginia Purchasing Bulletin Within the Vendor Self‐Service Portal at Wvoasis.Gov

The following documentation is an electronically‐ submitted vendor response to an advertised solicitation from the West Virginia Purchasing Bulletin within the Vendor Self‐Service portal at wvOASIS.gov. As part of the State of West Virginia’s procurement process, and to maintain the transparency of the bid‐opening process, this documentation submitted online is publicly posted by the West Virginia Purchasing Division at WVPurchasing.gov with any other vendor responses to this solicitation submitted to the Purchasing Division in hard copy format. Purchasing Division State of West Virginia 2019 Washington Street East Solicitation Response Post Office Box 50130 Charleston, WV 25305-0130 Proc Folder : 338837 Solicitation Description : Addendum 1 - Vehicle Maintenance and Repair Management Serv. Proc Type : Central Master Agreement Date issued Solicitation Closes Solicitation Response Version 2017-06-13 SR 0215 ESR06121700000006243 1 13:30:00 VENDOR 000000115021 AUTOMOTIVE RENTALS INC Solicitation Number: CRFQ 0215 FLT1700000006 Total Bid : $0.00 Response Date: 2017-06-12 Response Time: 12:03:16 Comments: FOR INFORMATION CONTACT THE BUYER Linda B Harper (304) 558-0468 [email protected] Signature on File FEIN # DATE All offers subject to all terms and conditions contained in this solicitation Page : 1 FORM ID : WV-PRC-SR-001 Line Comm Ln Desc Qty Unit Issue Unit Price Ln Total Or Contract Amount 1 See Section 4.2.2 1.00000 EA Comm Code Manufacturer Specification Model # 78181507 Extended Description : VENDOR MUST FILL OUT EXHIBIT A PRICING PAGE AND SUBMIT IT WITH THIS BID Comments: ARI has included our bid quotes in Exhibit A of the attachments. -

Download Our Getting Settled Guide

American Express proudly sponsors this practical guide. TASIS England is pleased to accept the American Express Card for school fee payments. Contents Preparing for: Your New Life in the TASIS England Area 1 I. Finding a Home 2 II. Interim Living 6 III. Getting Around 8 Top TASIS Towns 10 Assistance with Settling: The Emotional and Practical Sides to Relocation 33 Parents’ Information and Resource Committee (PIRC) Resources 35 Preparing for an International Move 36 Local Expat Organizations 40 Land and People 41 Important Contact Information 44 Medical Care 45 Banking 48 Telephone, Mobile Phone, Internet Service, and Television 49 Driving 54 Public Transportation 57 Household 59 Kennels/Catteries 61 Postal Services 62 Shopping 63 Faith Communities in the TASIS Area 67 Family Fun 69 Sept20 Your New Life in the TASIS England Area All information and links contained here were current at the time this document was compiled. TASIS The American School in England cannot endorse specific businesses or individuals. The options are listed to augment and facilitate your own investigations. Please consider all options carefully before making important decisions based on this limited information. If you find that any information listed here is in error, please contact [email protected]. TOP TASIS TOWNS Virginia Water Weybridge Ascot Walton-on-Thames Egham Sunningdale Richmond Englefield Green Windsor Woking Sunninghill Windlesham These are the most popular towns among TASIS families because of their locations. Information about each town can be found in the Top TASIS Towns section, beginning on page 10. 1 I. FINDING A HOME The following websites provide listings of properties, including descriptions and prices, available within a particular town or postcode. -

Matahari Putra Prima (MPPA IJ)

Indonesia Initiating Coverage 6 July 2021 Consumer Non-cyclical | Retail - Staples Matahari Putra Prima (MPPA IJ) Buy The Rising Phoenix; Initiate BUY Target Price (Return): IDR1,750 (+50%) Price: IDR1,170 Market Cap: USD606m Avg Daily Turnover (IDR/USD) 81,591m/5.66m Initiate coverage with a BUY and IDR1,750 TP, 50% upside. Matahari Putra Analysts Prima’s recent revamping of initiatives should help to transform its business and keep it ahead of competitors. A strong focus on digital initiatives – particularly Indonesia Research Team the collaboration with Indonesia’s largest technology group GoTo – will likely +6221 5093 9888 lead to greater monetisation from the e-groceries trend. Our SOP-based TP is [email protected] derived from 1.7x 2023F P/S (fresh products) and 11.0x 2023F EV/BITDA (non- fresh products). Possible additional investment from GoTo is a likely catalyst to its share price. Michael Setjoadi Internal business transformation on the cards. The company aims to strongly +6221 5093 9844 [email protected] focus on expanding sales of its fresh products. We are positive on this strategy given less intense competition in the segment and this strategy may work well, supported by its strong merchandising programme (ie partnership with Disney), Marco Antonius Indonesian Ulama Council’s (MUI) halal assurance system (HAS) and strong +6221 5093 9849 logistics facilities. The company will also continue its expansion with a new, [email protected] smaller efficient yet modern hypermarket format, yielding better productivity and efficiency. This should help MPPA penetrate into residential areas, as well as Tier II and III cities. -

Development Advisory Committee Minutes

DEVELOPMENT ADVISORY COMMITTEE MINUTES The Development Advisory Committee (DAC) met on November 1, 2017 at 9:00 a.m. in the First Floor Conference Room, 220 S. Main Street, Bel Air, Maryland. The meeting was chaired by Moe Davenport, Department of Planning and Zoning. The following members were in attendance: Moe Davenport Chairman, DAC Robin Wales Department of Emergency Services Patrick Jones Soil Conservation District Len Walinski Health Department Daryl Ivins Water & Sewer Mike Rist DPW Engineering Sheriff’s Office Rich Zeller State Highway Administration Eric Vacek Planner, Development Review Also in attendance: Duy Do Nichole Do Maureen Cornett Irene Kane Robert Boyd Donna Blasdell Douglas Kopeck Ted Hendricks Lee Crush Robert Crush Donald Merritt Theaux LeGardeur Richard Foard Kevin T Jake Adler Shivarse Moberly Moe Davenport, of the Department of Planning and Zoning, welcomed everyone to the meeting. He explained there is one plan on the agenda. Mr. Davenport explained that a brief presentation will be given by the consultant for the project. The DAC members will give their comments on the project. The meeting will then be opened up for anyone in attendance that may have questions or comments. If anyone has questions that are not answered, there are information request forms that can be filled out and submitted to the Department of Planning and Zoning and they will be responded to in writing. There is an attendance sheet circulating for everyone to sign. If a correct address is given, a copy of the minutes will be mailed or e-mailed. The minutes are recorded and will also be published to the Department of Planning and Zoning’s website. -

Participant Station Address City State Shell/Equiva Service Shell Rte 8 & Great Hill Rd Ansonia Ct Exxonmobil Squaw Hollow X

PARTICIPANT STATION ADDRESS CITY STATE SHELL/EQUIVA SERVICE SHELL RTE 8 & GREAT HILL RD ANSONIA CT EXXONMOBIL SQUAW HOLLOW X 9 NOTT HWY ASHFORD CT CITGO PETROLEUM CORP CITGO 23908079 AVON 75 EAST MAIN STREET AVON CT EXXONMOBIL AVON 80 EAST MAIN STREET AVON CT EXXONMOBIL SOUCEY ENTERPR 411 WEST MAIN STREET AVON CT CITGO PETROLEUM CORP CITGO 26514517 FOOD 77 GREENWOOD AVE BETHEL CT EXXONMOBIL GRASSY PLAIN S 33-35 GRASSY PLAIN ST BETHEL CT SHELL/EQUIVA SERVICE SHELL 203 GREENWOOD AVE BETHEL CT EXXONMOBIL BRANMAR SERVIC 985 BLUE HILLS AVE BLOOMFIE CT CITGO PETROLEUM CORP CITGO 15458003 BLOOM 925 BLUE HILL AVE BLOOMFIELD CT SHELL/EQUIVA SERVICE SHELL 47 JEROME AVE BLOOMFIELD CT CITGO PETROLEUM CORP CITGO 19328011 M&M O 271 HOP RIVER ROAD BOLTON CT EXXONMOBIL GARY JACKOPSIC 129 BOSTON TPKE BOLTON CT CITGO PETROLEUM CORP CITGO 13821105 A AND 117 N MAIN STREET BRANFORD CT EXXONMOBIL CHUCKYS BRNDFD 364 E MAIN ST BRANFORD CT EXXONMOBIL DEAN EVANS 108 N MAIN ST BRANFORD CT EXXONMOBIL OPAL VENTURES 48 LEETES ISLAND ROAD BRANFORD CT EXXONMOBIL E & M PARK FUE 1705 PARK AVENUE BRIDGEPO CT EXXONMOBIL BRIDGEPORT 565 LINDLEY ST BRIDGEPO CT EXXONMOBIL SABA 1360 NOBLE AVE BRIDGEPO CT CITGO PETROLEUM CORP CITGO 24899175 STATE 900 STATE STEET BRIDGEPORT CT CITGO PETROLEUM CORP CITGO 20524016 SALMA 915 RESERVOIR AVE BRIDGEPORT CT SHELL/EQUIVA SERVICE SHELL 4402 MAIN STREET BRIDGEPORT CT EXXONMOBIL MARTYS 11 NEW MILFORD RD WEST BRIDGEWA CT CITGO PETROLEUM CORP CITGO 14253014 A & J 36 EAST MAIN STREET BRISTOL CT CITGO PETROLEUM CORP CITGO 26514005 FOOD 396 BIRCH -

Wikipedia List of Convenience Stores

List of convenience stores From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The following is a list of convenience stores organized by geographical location. Stores are grouped by the lowest heading that contains all locales in which the brands have significant presence. NOTE: These are not ALL the stores that exist, but a good list for potential investors to research which ones are publicly traded and can research stock charts back to 10 years on Nasdaq.com or other related websites. [edit ] Multinational • 7-Eleven • Circle K [edit ] North America Grouping is by country or united States Census Bureau regional division . [edit ] Canada • Alimentation Couche-Tard • Beckers Milk • Circle K • Couch-Tard • Max • Provi-Soir • Needs Convenience • Hasty Market , operates in Ontario, Canada • 7-Eleven • Quickie ( [1] ) [edit ] Mexico • Oxxo • 7-Eleven • Super City (store) • Extra • 7/24 • Farmacias Guadalajara [edit ] United States • 1st Stop at Phillips 66 gas stations • 7-Eleven • Acme Express gas stations/convenience stores • ampm at ARCO gas stations • Albertsons Express gas stations/convenience stores • Allsup's • AmeriStop Food Mart • A-Plus at Sunoco gas stations • A-Z Mart • Bill's Superette • BreakTime former oneer conoco]] gas stations • Cenex /NuWay • Circle K • CoGo's • Convenient Food Marts • Corner Store at Valero and Diamond Shamrock gas stations • Crunch Time • Cumberland Farms • Dari Mart , based in the Willamette Valley, Oregon Dion's Quik Marts (South Florida and the Florida Keys) • Express Mart • Exxon • Express Lane • ExtraMile at -

Jones Et Al. (2018) Accessibility of Businesses WAVES Study GIS

Accessibility of businesses: Weight and Veterans’ Environments Study GIS protocol Jones KK, Xiang W, Matthews SA, Zenk SN. Weight and Veterans’ Environments Study Overview This protocol describes the process through which WAVES processed commercial business list data. We include sections on measure definitions, bias assessments, and deduplication. Finally, we include a section describing how we used the processed business list data to create national raster surfaces showing neighborhood environment measures. Acknowledgements This protocol was developed with grant support from the National Cancer Institute (R21CA195543) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (IIR 13-085), co-led by Shannon Zenk and Elizabeth Tarlov. We thank Lisa Powell, Irina Horoi, Sandy Slater for input into this protocol. Haytham Abu Zayd, Shubhayan Ukil and Abby Klemp helped to edit the protocol for dissemination. Suggested Citation Jones K, Xiang W, Matthews SA, Zenk SN. (2018). Accessibility of businesses: Weight and Veterans’ Environments Study GIS protocol, Version 1. Retrieved from Weight and Veterans’ Environments Study website: https://waves.uic.edu/. 2 http://waves.uic.edu/ Version 1, April 2018 Weight and Veterans’ Environments Study Table of Contents Overview ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................................