Annual Report 2019/20 SUMMARY in ENGLISH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Functions of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Future Generations Dr

The functions of the Parliamentary Commissioner for future generations Dr. Sandor Fulop PhD National University of Public Services, Budapest, Hungary, Department of Sustainable Development (former Parliamentary Ombudsman for Future Generations in Hungary) History of the ombudsman institution • China, during the Qin Dynasty (221 BC) • Korea, during the Joseon Dynasty • The Roman Empire, People’s Tribune • Turkish Diwan-al-Mazalim (634–644) • Also in Siam, India, the Liao Dynasty (Khitan Empire), Japan • Swedish Parliamentary Ombudsman, instituted by the Instrument of Government of 1809, to safeguard the rights of citizens by establishing a supervisory agency independent of the executive branch. The predecessor of the Swedish Parliamentary Ombudsman was the Office of Supreme Ombudsman, which was established by the Swedish King, Charles XII, in 1713. Charles XII was in exile in Turkey and needed a representative in Sweden to ensure that judges and civil servants acted in accordance with the laws and with their duties. If they did not do so, the Supreme Ombudsman had the right to prosecute them for negligence. The contemporary ombudsman institution • On constitutional basis they control the executory branch of power on/in behalf of the Parliament • Therefore, independent from the government • All access to administrative information, but no or very weak administrative power • Rich social ties, especially with the local communities whose complaints should be addressed • Parliamentary (and broader legislative) advocacy for better laws The age -

The Original Recipe: 200 Years of Swedish Experience

The Original Recipe: 200 Years of Swedish Experience Hans-Gunnar Axberger, Parliamentary Ombudsman, Sweden Back to Roots: Tracing the Swedish Origin of Ombudsman Institutions Friday, June 12, 2009 The ombudsman institution has come a long way, from its first incarnation as the prosecutor for the Swedish King (1713), to the Parliamentary or Justice Ombudsman of 1809, whose anniversary we celebrate today. This paper traces the history of the institution and examines the question: Whom does the ombudsman represent? Parliament? The public at large? The complaining citizen? The cause of human rights? In the original Swedish recipe, the om- budsman was conceived as the independent watchdog of Parliament – and remains so today. As the historical outline shows, the JO is part of a Swedish "Rule of Law"-doctrine. In this sense the JO differs from many of the world's more modern ombudsman institutions. Introduction Those of you who have attended this week's conference might think that you have heard enough about Swedish history by now. Unfortunately, I will have to dwell a little more on the subject, since I have been entrusted with describ- ing the origins of the Swedish ombudsman. They go way back, but I will try to make the historical account short and painless, with the help of some pic- tures [excluded here]. The first ombudsman This is not the first ombudsman. It is a portrait of Karl XII, one of the rela- tively few outstanding personalities among Swedish kings. When he was fourteen years of age his father, Karl XI, another of the outstanding few, passed away. -

The Danish Ombudsman – a National Watchdog with European Reservations

THE DANISH OMBUDSMAN – A NATIONAL WATCHDOG WITH EUROPEAN RESERVATIONS Michael GØTZE Associate Professor Research Centre of Legal Studies on Welfare and EU Market Integration Faculty of Law, University of Copenhagen Tel.: + 45 35323178 Email: [email protected] Abstract The Danish Parliamentary Ombudsman occupies a central position as a watchdog over public authorities within the national context. The statutory and functional powers of the institution are wide and the ombudsman enjoys an a priori sympathy from e.g. Parliament and the media. In addition, there are no specialised administrative courts in Denmark and the ombudsman is thus unrivalled on the legal scene as the primary specialist protector of good administration. Nevertheless, the ombudsman subscribes to a narrow scope of focus in the protection of citizens’ rights. In practice the ombudsman often limits his review to the compliance by authorities of national law and in particular of general procedural requirements. The rights of citizens are only actively protected by the ombudsman as far as certain parts of general administrative law in concerned. The current strategy of selected preferences of the Danish ombudsman leaves European Union rights of citizens largely unidentified and unprotected. The Danish ombudsman is a watchdog with teeth but with discerning taste buds. As to EU Law, the ombudsman is reserved and has no appetite at all. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 172 No. 28 E SI/2009 pp. 172-193 1. Introduction The Danish Parliamentary Ombudsman is one of the oldest ombudsman institutions in the world and occupies a central position as a watchdog over public authorities within the national context. -

The Swedish Justitieombudsman*

THE YALE LAW JOURNAL VOLUm 75 NOVEMBER 1965 No. 1 THE SWEDISH JUSTITIEOMBUDSMAN* WALTER GELLHORNt How IT ALL BEGAN MucIH of the Swedish Constitution of 1809 has been forgotten; its delineation of royal powers and parliamentary structure has little relevance to today's realities. But the office it created, that of the Jus- titieombudsman, has lived and grown. It has inspired similar establish- ments in Finland, Denmark, Norway, and New Zealand, and has added the word "Ombudsman" to the international vocabulary.' When in 1713, Swedish King Charles XII appointed a representative, an Ombudsman, to keep an eye on the royal officials of that day, he simply responded to the passing moment's need. He was bogged down in seemingly endless campaigns at the head of his army and in diplomatic negotiations that followed them. And so, very possibly ignorant that an overly-occupied Russian monarch had previously done the very same thing, he sensibly commissioned a trusted subordinate to scrutinize the conduct of the tax gatherers, the judges, and the few other law adminis- trators who acted in his name at home. What had begun as a temporary expedient became a permanent element of administration, under the title of Chancellor of Justice. A century passed. The fortunes of the monarchy ebbed and then again grew large, but at last royal government was bridled and Sweden took hesitant steps toward representative democracy. Nothing would do then but that the parliament should have its own overseer of adminis- * Copyright 1965 by Walter Gelihorn. The substance of this article will appear in a volume to be published by the Harvard University Press in 1966. -

Ombuds Institutions for the Armed Forces: Selected Case Studies

Ombuds Institutions for the Armed Forces: Selected Case Studies DCAF DCAF a centre for security, development and the rule of law Ombuds Institutions for the Armed Forces: Selected Case Studies DCAF DCAF a centre for security, development and the rule of law The Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) is one of the world’s leading institutions in the areas of security sector reform and security sector governance. DCAF provides in-country advisory support and practical assistance programmes, develops and promotes appropriate democratic norms at the international and national levels, advocates good practices and conducts policy-related research to ensure effective democratic governance of the security sector. Published by DCAF Maison de la Paix Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E 1202 Geneva Switzerland www.dcaf.ch ISBN: 978-92-9222-429-5 Editorial Assistants: William McDermott, Kim Piaget Design: Alice Lake-Hammond, alicelh.co Copy editor: Kimberly Storr Cover photo: Belinda Cleeland © 2017 DCAF DCAF gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) via its “Contribution to DCAF-OSCE project financing in the context of Switzerland’s OSCE chairmanship and OSCE Trojka membership. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors of the individual case studies and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the editors or the institutions referred to or represented within this study. DCAF is not responsible for either the views expressed or the accuracy of facts and other forms of information contained in this publication. All website addresses cited in the handbook were available and accessed in November 2016. -

The Swedish Justitieombudsman*

THE YALE LAW JOURNAL VOLUm 75 NOVEMBER 1965 No. 1 THE SWEDISH JUSTITIEOMBUDSMAN* WALTER GELLHORNt How IT ALL BEGAN MucIH of the Swedish Constitution of 1809 has been forgotten; its delineation of royal powers and parliamentary structure has little relevance to today's realities. But the office it created, that of the Jus- titieombudsman, has lived and grown. It has inspired similar establish- ments in Finland, Denmark, Norway, and New Zealand, and has added the word "Ombudsman" to the international vocabulary.' When in 1713, Swedish King Charles XII appointed a representative, an Ombudsman, to keep an eye on the royal officials of that day, he simply responded to the passing moment's need. He was bogged down in seemingly endless campaigns at the head of his army and in diplomatic negotiations that followed them. And so, very possibly ignorant that an overly-occupied Russian monarch had previously done the very same thing, he sensibly commissioned a trusted subordinate to scrutinize the conduct of the tax gatherers, the judges, and the few other law adminis- trators who acted in his name at home. What had begun as a temporary expedient became a permanent element of administration, under the title of Chancellor of Justice. A century passed. The fortunes of the monarchy ebbed and then again grew large, but at last royal government was bridled and Sweden took hesitant steps toward representative democracy. Nothing would do then but that the parliament should have its own overseer of adminis- * Copyright 1965 by Walter Gelihorn. The substance of this article will appear in a volume to be published by the Harvard University Press in 1966. -

Journal Article Databaseweb

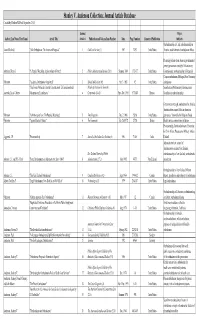

Stanley V. Anderson Collection: Journal Article Database Created by Matthew M. Peek (September 2010) Journal Major Author (Last Name, First Name) Article Title Article # Publication and Volume/Issue Number Date Page Numbers Country of Publication Subjects Ombudsmanship in Utah; ombudsmanship in Aaron, Richard I. "Utah Ombudsman: The American Proposals" 1 Utah Law Review (1) 1967 32-93 United States America; establishment of ombudsman offices Protecting citizens from abuse of governmental power; government oversight; Parliamentary Abraham, Henry J. "A People's Watchdog Against Abuse of Power" 2 Public Administration Review (20.3) Summer 1960 152-157 United States Commissioner; ombudsmanship in Denmark Campus ombudsmen; Michigan State University Unknown "Academic Ombudsman Appointed" 3 School and Society (96) Feb. 3, 1968 62 United States ombudsman "Una Forma Politica de Control Constitucional: El Comisionado del Boletín del Instituto de Derecho Scandinavian Parliamentary Commissioner; Acevedo, Lucio Cabrera Parlamento en Escandinavia" 4 Comparado (14.42) Sept.-Dec. 1961 573-580 Mexico Scandinavian ombudsmanship Government oversight; ombudsman for America; administrative counsel; African-American Unknown "Administrative Law: The People's Watchdog" 5 Time Magazine Dec. 2, 1966 58, 60 United States grievances; National Labor Relations Board Unknown "Against Doctors' Orders" 6 The Economist Feb. 26, 1972 27-28 Britain Health service commissioner in Britain Procuratorship; Justitieombudsman ; Procurator for Civil Affairs; Procurator of Military Affairs; Aggarwal, J.P. "Procuratorship" 7 Journal of the Indian Law Institute (3) 1961 71-86 India Finland Administrative law; control of administrative action in New Zealand; New Zealand Journal of Public ombudsmanship in New Zealand; ombudsman's Aikman, C.C. and R.S. Clark "Some Developments in Administrative Law (1964)" 8 Administration (27.2) Mar. -

Ombudsman in the Third World: the Latin American Case

Ombudsman in the Third World: The Latin American Case Elton Simoes Andrea Maia Find Resolution, Brazil [email protected] [email protected] Introduction Literally translated from its origins in Old Norse, the word “umbuds man” is a gender neutral term which means “representative”. It is also used in other Scandinavian languages such as Norwegian (“ombudsman”); Icelandic (“umbo”); and Danish (“Ombudsman”). The expression Ombudsman, however, originates from the Swedish usage, initiates with the establishment of the parliamentary ombudsman in 1809, whose function was to protect citizens rights through an independent (from the executive branch of the government) institution. Both the word and its meaning have been adopted by other languages (Friedery, 2008). Some scholars believe that the origins of the ombudsman institution in Scandinavia lie on Turkey. According to this view, In 1712, when the Swedish king Charles XII lost the Poltava battle against the Russian Czar and sought refuge in Turkey, where he stayed over a decade, under the protection of the Turkish Emperor. Charles XII would have been inspired by the Diwan al-Mazalim, a Turkish institution that loosely translates as “board of grievances”, whose office holder (Muhtashib) was entitled and obligated to check complaints of individuals against authorities, by using a non-legal review to protect those people who were victims of the official’s injustice, discrimination and unfairness. Charles XII adopted this concept and implemented the King’s Ombudsman. In 1809, the Swedish Ombudsman idea gained force when a constitutional reform gave the Swedish legislative body the right to elect an Ombudsman of justice, after having disputed this right with the king for almost a century (Friedery, 2008). -

Berlin Conference Report

Oversight, protection and welfare: The ombudsman institutions as advocates for military personnel Proceedings of the international conference on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the German Parliamentary Commissioner for the Armed Forces Bundestag, Berlin, 10 - 12 May 2009 co-hosted by Reinhold Robbe, German Parliamentary Commissioner for the Armed Forces and Ambassador Theodor H. Winkler, Director of the Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) Reinhold Robbe Der Wehrbeauftragte des Deutschen Bundestages - 2 - - 3 - TABLE OF CONTENTS OPENING CEREMONY ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Welcome remarks and opening of the conference by Reinhold Robbe, German Parliamentary Commissioner for the Armed Forces ................................................................................................ 5 Welcome remarks and opening of the Conference by Ambassador Theodor H. Winkler, Director of the Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) ................................. 19 Welcoming address by Günter Gloser, MdB, Minister of State for Europe at the Federal Foreign Office ................................................................................................................................................. 23 Welcoming address by Dr Franz-Josef Jung, MdB, Federal Minister of Defence .......................... 29 Welcoming address by Ulrike Merten, MdB, Chair of the Defence -

Report of the Non-Discrimination Ombudsman to the Parliament

K 6/2018 vp THE REPORT OF THE NON-DISCRIMINATION OMBUDSMAN TO THE PARLIAMENT 2018 FINLAND CONTENTS The Ombudsman’s foreword: Stories, deeds and accomplishments for equality ............................................... 4 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. The significance of human rights is emphasised in difficult times ..................................................... 6 1.2. Progress towards full enforcement of human rights .......................................................................... 6 1.3. Racism ............................................................................................................................................... 7 1.4. Vulnerability is created and prevented with structures ....................................................................... 8 1.5. The Non-Discrimination Ombudsman’s office ..................................................................................... 9 2. Equality brings legal protection to all ............................................................................................................. 12 2.1. Non-discrimination act provides low-threshold measures for combating discrimination ............... 13 2.1.1. Prohibition of discrimination in the non-discrimination act and the criminal code .......... 13 2.1.2. National Non-Discrimination and Equality Tribunal ......................................................... -

E U R O P E a N P a R L I a M E

E U R O P E A N P A R L I A M E N T DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR RESEARCH WORKING PAPER EUROPEAN OMBUDSMAN AND NATIONAL OMBUDSMEN OR SIMILAR BODIES - COMPARATIVE TABLES - Political Series POLI 117 EN This paper is published in the following languages : EN, FR This working document replaces and updates the previous paper W-6 of the Peoples' Europe Series. At the end of this document please find a full list of the other publications in the Political Series. Publisher: European Parliament L - 2929 Luxembourg Author: Marília CRESPO ALLEN Principal Administrator International and Constitutional Affairs Division Directorate-General for Research and Documentation Tel: +32/2/284-3702 Fax: +32/2/284-9050 e-mail: [email protected] The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Parliament. Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised provided the source is acknowledged and the publisher is given prior notice and sent a copy. Manuscript completed in February 2001. E U R O P E A N P A R L I A M E N T DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR RESEARCH WORKING PAPER EUROPEAN OMBUDSMAN AND NATIONAL OMBUDSMEN OR SIMILAR BODIES - COMPARATIVE TABLES - Political Series POLI 117 EN 03-2001 European Ombudsman and National Ombudsmen or similar bodies CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................5 II. GENERAL REMARKS ...................................................................................................7 -

The Role of Ombudsman Institutions in Open Government OECD Working Paper on Public Governance No

The Role of Ombudsman Institutions in Open Government OECD Working Paper on Public Governance No. 29 OECD working papers on Public Governance Acknowledgements This series gathers together OECD working papers on the This report was prepared by the Governance Reviews and tools, institutions and practices of public governance. It Partnerships Division, led by Martin Forst, of the OECD includes both technical and analytical material, prepared by Public Governance Directorate, headed by Marcos Bonturi. staff and experts in the field. It was developed under the strategic direction of Alessandro Bellantoni, Head of the OECD Open Government Unit and Together, the papers provide valuable context and Deputy Head of the Governance Reviews and Partnerships background for OECD publications on regulatory policy and Division. Emma Cantera provided comments on the narrative governance. and the analysis of the data. The report was drafted by Katharina Zuegel, with the support of Claudia Quintana and OECD working papers should not be reported as Mariachiara Iannuzzi, who also co-ordinated the survey and representing the official views of the OECD or of its Member qualitative interviews through which data were collected. countries. The opinions expressed and arguments employed Editorial work and quality control were carried out by Julie are those of the authors. Harris. Amelia Godber and Roxana Glavanov prepared the manuscript for publication. Administrative support was Working papers describe preliminary results or research provided by Lauren Thwaites and Caroline Semery. in progress by the authors and are published to stimulate discussion on a broad range of issues on which the OECD works. The OECD Secretariat wishes to express its gratitude to all those who made this report possible, especially to all Comments on working papers are welcomed, and may the representatives of the 94 ombudsman institutions be sent to either [email protected] or the Public that participated in the survey.