Political Rhetoric in Post-9/11 Popular Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organized Crime and Terrorist Activity in Mexico, 1999-2002

ORGANIZED CRIME AND TERRORIST ACTIVITY IN MEXICO, 1999-2002 A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the United States Government February 2003 Researcher: Ramón J. Miró Project Manager: Glenn E. Curtis Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540−4840 Tel: 202−707−3900 Fax: 202−707−3920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://loc.gov/rr/frd/ Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Criminal and Terrorist Activity in Mexico PREFACE This study is based on open source research into the scope of organized crime and terrorist activity in the Republic of Mexico during the period 1999 to 2002, and the extent of cooperation and possible overlap between criminal and terrorist activity in that country. The analyst examined those organized crime syndicates that direct their criminal activities at the United States, namely Mexican narcotics trafficking and human smuggling networks, as well as a range of smaller organizations that specialize in trans-border crime. The presence in Mexico of transnational criminal organizations, such as Russian and Asian organized crime, was also examined. In order to assess the extent of terrorist activity in Mexico, several of the country’s domestic guerrilla groups, as well as foreign terrorist organizations believed to have a presence in Mexico, are described. The report extensively cites from Spanish-language print media sources that contain coverage of criminal and terrorist organizations and their activities in Mexico. -

Annotated Bibliography of Non-Fiction Dvds

Resources for Teachers: Nonfiction DVDs to Use in the Classroom Famous Historical Figures Edison - DVD 621.3 Edi Documentary about Thomas Edison that explores the complex alchemy that accounts for the enduring celebrity of America's most famous inventor. It offers new perspectives on the man and his milieu, and illuminates not only the true nature of invention, but its role in turn-of-the-century America's rush into the future. Rating: TV-PG In Search of Shakespeare - DVD 822.3 In An intimate look at William Shakespeare and his world. Rating: Not Rated Johann Sebastian Bach - DVD 921 Bach, J. One of the greatest composers in Western musical history, Bach created masterpieces of choral and instrumental music. More than 1,000 of his works survive from every musical form and genre in use in 18th century Germany. During his lifetime, he was appreciated more as an organist than a composer. It was not until nearly a century after his death that a musical public came to appreciate his body of work. Rating: Not Rated Ludwig Van Beethoven - DVD 921 Beethoven, L. One of the greatest masters of music, Beethoven is particularly admired for his orchestral works. The highly expressive music Beethoven produced, inspired composers like Brahms, Mendelssohn, and Wagner. Rating: Not Rated George Fredric Handel 1685-1759 - DVD 921 Handel, G. Presents a factual outline of Handel's life and an overview of his work. Handel's greatest gift to posterity was undoubtedly the creation of the dramatic oratorio genre, partly out of existing operatic traditions and partly by force of his own musical imagination. -

Austria: Jewish Family History Research Guide

Courtesy of the Ackman & Ziff Family Genealogy Institute Revised June 2012 Updated March 12, 2013 Austria: Jewish Family History Research Guide Austria Like most European countries, Austria’s borders have changed considerably over time. In 1690 the Austrian Hapsburgs completed the reconquest of Hungary and Transylvania from the Ottoman Turks. From 1867 to 1918, Hungary achieved autonomy within the “Dual Monarchy,” or Austro-Hungarian Empire, as well as full control over Transylvania. After World War I, Austro-Hungry was split up among various other countries, so that areas formerly under Austro-Hungarian jurisdiction are today located within the borders of Austria, Bosnia, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia and the Ukraine. The primary focus of this fact sheet is Austria within its post World War II borders. Fact sheets for other countries formerly part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire are also available. How to Begin Follow the general guidelines in our fact sheets on starting your family history research, immigration records, naturalization records, and finding your ancestral town. Determine whether your town is still within modern-day Austria, and in which county and district it is located. A good resource for starting your research is “Beginner’s Guide to Austrian Jewish Genealogy” by E. Randol Schoenberg. This manual is accessible on the jewishgen Austria-Czech Special Interest Group (SIG) website, www.jewishgen.org/AustriaCzech. Records • Depending on the time period, records may be in several languages: German, Hungarian, Hebrew, or Latin. • By decree of the Austrian Emperor, in 1787 all Jews within the Empire were required to adopt German surnames. -

Labarthe Thomas Alias Toma-L

LABARTHE THOMAS ALIAS TOMA-L Frevo BIOGRAPHY Thomas Labarthe was born in France in 1975. He lives and works in Nantes. It was at the Pompidou Centre in October 2001 that Thomas Labarthe frst discovered Jean Dubuffet. The retrospective exhibition was like “a massive shock to my system”. His frst canvas, Mala bestia emerged three months later. Like André Breton and Jean Miro before him Thomas threw himself into a creative furry. The time for exhibitions would come later in Paris, Nantes and Tours. In 2009, Thomas met Sebastien Fritsch who would soon become his agent. Together, the two men set up a series of exhibitions and creative projects in the South of France. His artistic force is centrifugal and soon attracted other creative contributors: Film makers, photographers, authors, graphic designer, dancers and set designers united around him and numerous colla- borations ensued. The following decade proved to be one of the utmost creativity: his powerful graphic style was received en- thusiastically by the artistic community and with wide acclaim in Barcelona, Brussels and in Paris at the Galerie W Landau and Halle Saint Pierre. Museum. In May 2019, Toma-L then set up in the Frevo Gallery in Greenwich Village which has remained the seat of his activity in New York ever since. He toils in the fertile felds of Free Figuration, Lyrical Abstraction and of course Outsider Art and his efforts are not limited to canvas work. He regularly branches out to create hybrid projects in a move which echoes Gilles Deleuze theory that “The notion of a ‘territory’ can only really be qualifed by the action we take to get out of it” found in his work Abécédaire*. -

Cedric Jimenez

THE STRONGHOLD Directed by Cédric Jimenez INTERNATIONAL MARKETING INTERNATIONAL PUBLICITY Alba OHRESSER Margaux AUDOUIN [email protected] [email protected] 1 SYNOPSIS Marseille’s north suburbs hold the record of France’s highest crime rate. Greg, Yass and Antoine’s police brigade faces strong pressure from their bosses to improve their arrest and drug seizure stats. In this high-risk environment, where the law of the jungle reigns, it can often be hard to say who’s the hunter and who’s the prey. When assigned a high-profile operation, the team engages in a mission where moral and professional boundaries are pushed to their breaking point. 2 INTERVIEW WITH CEDRIC JIMENEZ What inspired you to make this film? In 2012, the scandal of the BAC [Anti-Crime Brigade] Nord affair broke out all over the press. It was difficult to escape it, especially for me being from Marseille. I Quickly became interested in it, especially since I know the northern neighbourhoods well having grown up there. There was such a media show that I felt the need to know what had happened. How far had these cops taken the law into their own hands? But for that, it was necessary to have access to the police and to the files. That was obviously impossible. When we decided to work together, me and Hugo [Sélignac], my producer, I always had this affair in mind. It was then that he said to me, “Wait, I know someone in Marseille who could introduce us to the real cops involved.” And that’s what happened. -

SORNA & Sex Offender Registration Quicksheet for Legal Professionals

Sex Offense Registration Quick sheet Offenses Requiring Registration Statute Offense Registration 18 – 2901 (a.1) Kidnapping (of a minor) Tier III (Life) 18 – 2902(b) Unlawful Restraint (Minor victim and offender not parent or guardian) Tier I (15 Years) 18 – 2903(b) False Imprisonment (Minor victim and offender not parent or guardian) Tier I (15 Years) 18 – 2904 Interference with Custody of Children Tier I (15 years) 18 – 2910 Luring Child into Motor Vehicle Tier I (15 Years) 18 – 3121 Rape Tier III (Life) 18 – 3122.1(a)(2) Statutory Sexual Assault Tier II (25 Years) 18 – 3122.1(b) Statutory Sexual Assault (11 or more years older than victim) Tier III (Life) 18 – 3123 Involuntary Deviant Sexual Intercourse Tier III (Life) 18 – 3124.1 Sexual Assault Tier III (Life) 18 – 3124.2(a) Institutional Sexual Assault Tier I (15 Years) 18 – 3124.2(a.1) Institutional Sexual Assault Tier III (Life) 18 – 3124.2(a.2-a.3) Institutional Sexual Assault Tier II (25 Years) 18 – 3125 Aggravated Indecent Assault Tier III (Life) 18 – 3126(a)(1) Indecent Assault (without consent) Tier I (15 Years) 18 – 3126(a)(2-6, 8) Indecent Assault Tier II (25 Years) 18 – 3126(a)(7) Indecent Assault (victim under 13) Tier III (Life) 18 – 4302(b) Incest (involving minor) Tier III (Life) 18 – 5902(b.1) Promoting Prostitution of a Minor Tier II (25 Years) 18 – 5903(a) Minor Victim - (a)(3)(ii), ((4)(ii), (5)(ii), (6) Tier II (25 Years) 18 - 6301(a)(1)(ii) Corruption of Minors (committing or inducing sexual offense) Tier I (15 Years) 18 – 6312(b)(c) Sexual Abuse of Children -

American Society

AMERICAN SOCIETY Prepared By Ner Le’Elef AMERICAN SOCIETY Prepared by Ner LeElef Publication date 04 November 2007 Permission is granted to reproduce in part or in whole. Profits may not be gained from any such reproductions. This book is updated with each edition and is produced several times a year. Other Ner LeElef Booklets currently available: BOOK OF QUOTATIONS EVOLUTION HILCHOS MASHPIAH HOLOCAUST JEWISH MEDICAL ETHICS JEWISH RESOURCES LEADERSHIP AND MANAGEMENT ORAL LAW PROOFS QUESTION & ANSWERS SCIENCE AND JUDAISM SOURCES SUFFERING THE CHOSEN PEOPLE THIS WORLD & THE NEXT WOMEN’S ISSUES (Book One) WOMEN’S ISSUES (Book Two) For information on how to order additional booklets, please contact: Ner Le’Elef P.O. Box 14503 Jewish quarter, Old City, Jerusalem, 91145 E-mail: [email protected] Fax #: 972-02-653-6229 Tel #: 972-02-651-0825 Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE: PRINCIPLES AND CORE VALUES 5 i- Introduction 6 ii- Underlying ethical principles 10 iii- Do not do what is hateful – The Harm Principle 12 iv- Basic human rights; democracy 14 v- Equality 16 vi- Absolute equality is discriminatory 18 vii- Rights and duties 20 viii- Tolerance – relative morality 22 ix- Freedom and immaturity 32 x- Capitalism – The Great American Dream 38 a- Globalization 40 b- The Great American Dream 40 xi- Protection, litigation and victimization 42 xii- Secular Humanism/reason/Western intellectuals 44 CHAPTER TWO: SOCIETY AND LIFESTYLE 54 i- Materialism 55 ii- Religion 63 a- How religious is America? 63 b- Separation of church and state: government -

Gabriel Orozco and .Dami ´An Ortega

Conversation Gabriel OrOzcO and .damia ´ n OrteGa Damián Ortega and Gabriel Orozco were friends and neighbors in Mexico people, especially Spanish-speaking City in the 1980s, years before they established international careers students who otherwise would have no as artists. Son of painter Mario Orozco Rivera, a longtime assistant to access to publications like these. the muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, Orozco (b. 1962, Jalapa, Veracruz) Some aspects of the project remind grew up in an artistic household, attended a prestigious art school and me of our Friday Workshops in the late was well traveled when he met the younger Ortega. By contrast, Ortega 1980s, which you proposed to do in my (b. 1967, Mexico City) is self-taught, except for weekly meetings with house. I liked the workshop idea right away because it was the initiative of a Orozco that evolved into an experimental art course over the span of younger artist. With Abraham Cruzville- some four years beginning in 1987. Along with artists Gabriel Kuri, gas, Gabriel Kuri and Dr. Lakra joining Abraham Cruzvillegas and Dr. Lakra (Jerónimo López Ramírez), they us, the workshop became a kind of established what they called the Taller de los Viernes (Friday Workshop) extra-official school that lasted four years. at Orozco’s home in the Tlalpan district, a provincial outpost during the During that time, information about what colonial era and now part of the capital’s urban sprawl. It was an oppres- was going on in the international art sive time politically in Mexico, where progressive thinking was routinely scene was very limited in Mexico. -

Alias Manager 4

CHAPTER 4 Alias Manager 4 This chapter describes how your application can use the Alias Manager to establish and resolve alias records, which are data structures that describe file system objects (that is, files, directories, and volumes). You create an alias record to take a “fingerprint” of a file system object, usually a file, that you might need to locate again later. You can store the alias record, instead of a file system specification, and then let the Alias Manager find the file again when it’s needed. The Alias Manager contains algorithms for locating files that have been moved, renamed, copied, or restored from backup. Note The Alias Manager lets you manage alias records. It does not directly manipulate Finder aliases, which the user creates and manages through the Finder. The chapter “Finder Interface” in Inside Macintosh: Macintosh Toolbox Essentials describes Finder aliases and ways to accommodate them in your application. ◆ The Alias Manager is available only in system software version 7.0 or later. Use the Gestalt function, described in the chapter “Gestalt Manager” of Inside Macintosh: Operating System Utilities, to determine whether the Alias Manager is present. Read this chapter if you want your application to create and resolve alias records. You might store an alias record, for example, to identify a customized dictionary from within a word-processing document. When the user runs a spelling checker on the document, your application can ask the Alias Manager to resolve the record to find the correct dictionary. 4 To use this chapter, you should be familiar with the File Manager’s conventions for Alias Manager identifying files, directories, and volumes, as described in the chapter “Introduction to File Management” in this book. -

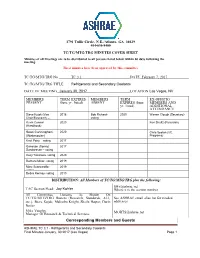

TC0301 Las Vegas Final Minutes 20170130

1791 Tullie Circle, N.E./Atlanta, GA 30329 404-636-8400 TC/TG/MTG/TRG MINUTES COVER SHEET Minutes of all Meetings are to be distributed to all persons listed below within 60 days following the meeting. These minutes have been approved by this committee TC/TG/MTG/TRG No. TC 3.1 DATE February 7, 2017 TC/TG/MTG/TRG TITLE Refrigerants and Secondary Coolants DATE OF MEETING January 30, 2017 LOCATION Las Vegas, NV MEMBERS TERM EXPIRES MEMBERS TERM EX-OFFICIO PRESENT (June yr. listed) ABSENT EXPIRES (June MEMBERS AND yr. listed) ADDITIONAL ATTENDANCE Steve Kujak (Vice 2018 Bob Richard- 2020 Warren Clough (Secretary) Chair/Research) – voting voting Kevin Connor 2020 Ken Shultz (Research) (Handbook) Sean Cunningham 2020 Chris Seeton (VC, (Webmaster) Programs) Knut Petry – voting 2017 Ganesan (Sonny) 2017 Sundaresan – voting Kenji Takizawa- voting 2020 Barbara Minor- voting 2019 Marc Scancarello- 2019 voting Debra Kennoy- voting 2019 DISTRIBUTION: All Members of TC/TG/MTG/TRG plus the following: [email protected] TAC Section Head: Jay Kohler Where x is the section number All Committee Liaisons As Shown On TC/TG/MTG/TRG Rosters (Research, Standards, ALI, See ASHRAE email alias list for needed etc.), Steve Kujak, Malcolm Knight, Sheila Hayter, Darin addresses. Nutter Mike Vaughn, [email protected] Manager Of Research & Technical Services Corresponding Members and Guests ASHRAE TC 3.1 - Refrigerants and Secondary Coolants Final Minutes January, 30 2017 (Las Vegas) Page 1 Mark McLinden Julie Majurin Greg Linteris Steve Brown Felix Flohr Robert Chevageo -

Double Agent

Double Agent InstItute of contemporAry Arts Double Agent pAWeŁ ALTHAMER / NOWolIpIe GROUP pHIl COLLIns DorA gArcÍA cHrISTOPH scHlINGENSIEF bARBArA VISSER DONELLE WOOLFORD ARTUR zmIJeWsKI curAteD by claire BisHop AnD MarK slADen InstItute of contemporAry Arts contents 09 IntroDuctIon claire bishop and mark sladen 13 pAWeŁ AltHAmer / pAWeŁ AltHAmer / NOWolIpIe group noWolIpIe group claire bishop 23 pHIl collIns stAgIng A terrAIn of sHAreD DesIre claire bishop and phil collins 35 DorA gArcÍA trA nscrIpt of INSTANT NARRATIVE (IN), 2006 – 08 49 cHrIstopH PERFORMING lIKe An ASYLUM SEEKER: scHlIngensIef pArADoXes of Hyper-AutHentIcIty In scHlIngensIef’s PLEASE LOVE AUSTRIA silvija Jestrovi c 63 bArbArA VIsser trAnscrIpt of LAST LECTURE, 2007 75 Donelle WoolforD DIscussIon WItH Donelle WoolforD At tHe IcA 95 Artur zmIJeWsKI Artur zmIJeWsKI AnD THEM, 2007 111 conteXtuAl mAterIAl 112 outsourcIng AutHentIcIty? DelegAteD performAnce In contemporAry Art claire bishop 128 performAnce In tHe serVIce economy: outsourcIng AnD DelegAtIon nicholas ridout 134 ArtIsts‘ bIogrApHIes 136 contrIbutors 138 colopHon 8 Double Agent prefAce 9 paweł althamer / nowolipie group In the early ’90s Paweł Althamer was among the first of a new generation of artists to produce events with non-professional performers; his early works in volv ed collaborations with homeless men and women, gallery invigilators, and children. IntroDuctIon Much of Althamer’s practice stems from his identi- fication with marginal subjects, and comes to claire bishop and mark sladen constitute an oblique form of self-portraiture. For over a decade, Althamer has led a ceramics class for the Nowolipie Group, an organisation in This book has been produced to accompany Warsaw for adults with multiple sclerosis and other the ICA exhibition Double Agent, an exhibition of disabilities. -

![BILLING CODE 3510-33-P DEPARTMENT of COMMERCE Bureau of Industry and Security 15 CFR Part 744 [Docket No. 201216-0348] RIN](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4538/billing-code-3510-33-p-department-of-commerce-bureau-of-industry-and-security-15-cfr-part-744-docket-no-201216-0348-rin-454538.webp)

BILLING CODE 3510-33-P DEPARTMENT of COMMERCE Bureau of Industry and Security 15 CFR Part 744 [Docket No. 201216-0348] RIN

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 03/04/2021 and available online at federalregister.gov/d/2021-04505, and on govinfo.govBILLING CODE 3510-33-P DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Bureau of Industry and Security 15 CFR Part 744 [Docket No. 201216-0348] RIN 0694-AI36 Addition of Certain Entities to the Entity List; Correction of Existing Entries on the Entity List AGENCY: Bureau of Industry and Security, Commerce ACTION: Final rule. SUMMARY: This final rule amends the Export Administration Regulations (EAR) by adding fourteen entities to the Entity List. These fourteen entities have been determined by the U.S. Government to be acting contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States. These fourteen entities will be listed on the Entity List under the destinations of Germany, Russia, and Switzerland. This rule also corrects six existing entries to the Entity List, one under the destination of Germany and the other five under the destination of China. DATE: This rule is effective [INSERT DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Chair, End-User Review Committee, Office of the Assistant Secretary, Export Administration, Bureau of Industry and Security, Department of Commerce, Phone: (202) 482-5991, Email: [email protected]. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Background The Entity List (15 CFR, Subchapter C, part 744, Supplement No. 4 of the Export Administration Regulations (EAR)) identifies entities reasonably believed to be involved, or to pose a significant risk of being or becoming involved in, activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States.