The Madras Geographical Association

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environmental Impact Assessment (Eia) Report

TAMIL NADU NEWSPRINT AND PAPERS LIMITED Kagithapuram, Karur District, Tamil Nadu MILL EXPANSION PLAN ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (EIA) REPORT March 2008 Prepared by VIMTA LABS LTD SPB PROJECTS AND CONSULTANCY LTD HYDERABAD CHENNAI PROJECT AT A GLANCE Project Promoters : Tamil Nadu Newsprint and Papers Limited Kagithapuram 639 136 Karur District, Tamil Nadu State Project : Mill Expansion Plan (MEP) Concept : Converting the surplus wet-lapped pulp into value-added products by installing a new paper machine #3 with power boiler by establishing more environment-friendly operations Paper Capacity Increase : From 245,000 tpa to 400,000 tpa. PROJECT HIGHLIGHTS Project Cost : Rs 725 Crores Cost for Environmental : Rs 10 Crores Management PROJECT OBJECTIVES To meet the growing demand for paper in the country and to maintain the leadership in the country and in export of newsprint and P&W papers/fine papers. To maintain the status of leading player in Indian Pulp and Paper Industry by achieving 1000 tpd paper production at a single location. To adopt energy efficient process and plant & machinery. To meet the growing demand for paper in the country. To facilitate the manufacture of more grades of environmentally friendly paper/products. To develop the existing green belt around the mill further. SALIENT FEATURES Installation of a new paper machine (PM #3) having an installed capacity of 155,000 tpa, for the manufacture of surface sized printing and writing and on- machine light-weight coated papers Reduction in the overall specific energy consumption with energy-efficient design of PM #3 at the rated production capacity. Balancing of chemical bagasse fibre line for achieving a production capacity from 500 tpd to 550 tpd has been planned by installing the following: • One (1) continuous digester of capacity 225 BD tpd unbleached bagasse pulp. -

Chennai District Tamil Nadu

For official use Technical Report Series DISTRICT GROUNDWATER BROCHURE CHENNAI DISTRICT TAMIL NADU By T. Balakrishnan, Scientist-D Government of India Ministry of Water Resources Central Ground Water Board South Eastern Coastal Region Chennai November 2008 DISTRICT AT A GLANCE (CHENNAI DISTRICT) S. No. ITEMS STATISTICS 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i. Geographical area (Sq. km) 174 ii. Administrative Divisions (As on 31-3-2007) Number of Taluks 5 Corporation 1 iii. Population (As on 2001 Census) Total Population 4343645 Male 2219539 Female 2124106 iv. Average Annual Rainfall (mm) 1200 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY i. Major physiographic Units 1. Fluvial land forms 2. Marine land forms 3. Erosional land forms ii. Major Drainages . 3. LAND USE (Sq. km) (2005-06) Adyar & Cooum i. Forest area 3 ii. Net area sown - iii. Cultivable area - 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES Beach sands, Clay & alluvial soils 5. NUMBER OF GROUND WATER MONITORING WELLS OF CGWB (As on 01.05.2008) i. Dug wells 11 ii. Piezometers 3 6. PREDOMINANT GEOLOGICAL Alluvium, sandstones FORMATIONS (argillaceous), clay, shale, silt stone, granites, gneisses and charnockite 7. HYDROGEOLOGY i. Major water bearing formations Sand, sandstone, weathered and fractured granites, gneisses and Charnockite ii. Pre monsoon depth to water level (May 2006) 2.21–7.64 m bgl iii. Post monsoon depth to water level (Jan. 2007) 0.45-5.32 m bgl iv. Long term water level trend in 10 years (1998- Annual 2007) (m/yr) Rise Fall Min: 0.003 Min:0. 04 Max: 0.93 Max:0. 78 i 8. GROUND WATER EXPLORATION BY CGWB (As on 31-03-2007) i. -

Evaluation and Planning of Urban Green Space Network in Landscape Planning of Ponneri, an Emerging Smart City in Tamil Nadu

International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (IJHSS) ISSN(P): 2319-393X; ISSN(E): 2319-3948 Vol. 5, Issue 5, Aug - Sep 2016; 39-46 © IASET EVALUATION AND PLANNING OF URBAN GREEN SPACE NETWORK IN LANDSCAPE PLANNING OF PONNERI, AN EMERGING SMART CITY IN TAMIL NADU K. NARMADA 1 & G. BHASKARAN 2 1Research Scholar, University of Madras, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India 2Assistant Professor, University of Madras, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India ABSTRACT Global human population and urban development are increasing at unprecedented rates and creating tremendous stress on local, regional and global air and water quality. Some of the major functions of the urban green spaces include reducing air pollution, providing shade and habitat for arboreal birds, producing oxygen, providing shelter against winds, recreational and aesthetic qualities. Cities and peri -urban Settlements must be prepared to meet the challenge of unplanned settlement or slum formation. The move towards smart cities promises to bring greater automation, intelligent routing and transportation, better monitoring and better city management. The development of urban green space networks includes creation of new spatial forms, restoration and maintenance of green patches connectivity as well as protection of existing green spaces. Green space network begins to be recognised as a medium of conserving ecosystem and natural environment in urban area. Several methods have been introduced in regards to formulation of modelling urban green space network. This research paper reviews several methods that are used for modelling green space network in urban planning. Recently, remote sensing and GIS are being used to produce a model of urban green space network which positively afford nature conservation in the city. -

District Disaster Management Plan for 201 8 Tiruvallur District

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR 201 8 TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT TMT.MAGESWARI RAVIKUMAR, I.A.S., DISTRICT COLLECTOR, TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT TAMIL NADU 2 DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT - 2018 INDEX Sl. DETAILS No PAGE NO. 1 Introduction 3-8 2 District Profile 9-16 Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Analysis with 3 17-58 sample maps & link to all vulnerable maps System approach for Sustainable Disaster Risk 4. 59-131 Management 5. Institutional Mechanism 132-140 6. Disaster Preparedness 141-152 7. Disaster Response Relief & Rehabilitation 153-162 8 Disaster Prevention and Mitigation 163-187 9 Build Back Better 188-197 Mainstreaming Disaster Risk Reduction into 10 195-212 Developmental planning 11 Financial Arrangements 213-215 12 Way Forward 216-233 Annexure Responsibility Matrix for Preparedness and a 234-239 Response State / District Agencies b List of NDMA Guidelines 240 c Abbreviations 241-242 d Important GOs 243 3 INTRODUCTION DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN – 2018 TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT Disaster: - Disaster means a catastrophe, mishap, calamity or grave occurrence affecting any area from natural and manmade causes, or by accident or negligence, which results in substantial loss of life or human suffering or damage to, and destruction of property, or damage to, or degradation of environment and of such a nature and magnitude as to be beyond the capacity of the community of the affected areas. Disaster Management:- Disaster management is a process or strategy that is implemented when any type of catastrophic event takes place. Sometimes referred to as disaster recovery management, the process may be initiated when anything threatens to disrupt normal operations or puts the lives of human beings at risk. -

Report of Public Hearing Held on Loss of Ecology and Fisher Livelihood in Ennore Creek

Death by a Thousand Cuts: Report of Public Hearing Held On Loss of Ecology and Fisher Livelihood in Ennore Creek April 2016 Organized by Ennore Anaithu Meenava Grama Kootamaipu with support from The Coastal Resource Centre of The Other Media www.coastalresourcecentre.wordpress.com Acknowledgement Sincere thanks to, Praveen Leo Gokul Kannan Dinesh Kumar Akhil Al Hasan G. Saranya Photographs and Maps : Saravanan K & Pooja Kumar, The Coastal Resource Centre For more details, contact : The Coastal Resource Centre #92, 3rd Cross Street Thiruvalluvar Nagar Besant Nagar Chennai 600090 Any part of this report may be freely reproduced for public interest purposes with appropriate acknowledgement . !2 Panel Profile Justice. D. Hariparanthaman is a retired Judge of the Madras High Court. He was in office between 2009-2016. Prior to that, he practiced labour law and represented solely, the interests of workers in many matters. Dr.S.Janakarajan, retired Professor of Economics in the Madras Institute of Development Studies MIDS, Adyar, and currently, President, South Asia Consortium for Interdisciplinary Water Resources Studies (SaciWATERs), obtained his Ph.D from Madras University, executed through MIDS. He has done his Post-Doctoral work at the Cornell University, USA. His areas of interest are agriculture and rural development, water management, environment, disaster management, climate change and adaptation, institutions and markets. Dr. Karen Coelho is an urban anthropologist and works as Assistant Professor at the Madras Institute of Development Studies. Having obtained her PhD from University of Arizona, her work focusses on the changing state and civil society formations in the context of reforms in urban governance. -

Flood Risk and Context of Land-Uses: Chennai City Case

Journal of Geography and Regional Planning Vol. 3(12), pp. 365-372, December 2010 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/JGRP ISSN 2070-1845 ©2010 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Flood risk and context of land-uses: Chennai city case Anil K. Gupta* and Sreeja S. Nair National Institute of Disaster Management (Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt of India), New Delhi- 110 002, India. Accepted 19 October, 2010 India witnessed increased flooding incidences during recent past especially in urban areas reportedly since Mumbai (2005) as a mega disaster. Other South Asian cities like Dhaka, Islamabad, Rawalpindi, besides many other cities in India, are also reportedly been affected by frequent floods. Flood risk in urban areas are attributed to hazards accelerated by growth in terms of population, housing, paved-up areas, waste disposal, vehicles, water use, etc. all contributing to high intensity – high load of runoff. Reduced carrying capacity of drainage channels is also a key concern. Haphazard growth of low- income habitations and un-organised trade added to challenge. Spatial dimensions of all these flood factors are often characterised by land-use and changes. Chennai, a coastal mega-city is fourth largest metropolis in India, has a history of over 350 years of growth. Meteorologically there is no major upward or downward trend of rainfall during 200 years, and a decrease in last 20 years with a contrast record of increasing floods have been experienced. Analysis of land-use changes over the temporal and spatial scale has been undertaken for Chennai city in order to understand the patterns on green- cover, built-up area and consequences on hydrological settings. -

An Application of Radial Basis Neural Network Function for Rainfall Prediction

ISSN: 0976-3104 ISSUE: Computer and Allied Sciences SPECIAL ARTICLE MATHEMATICAL APPROACH TOWARDS RECENT INNOVATION IN COMPUTATION AND ENGINEERING SYSTEM (MATRICS) AN APPLICATION OF RADIAL BASIS NEURAL NETWORK FUNCTION FOR RAINFALL PREDICTION Nirmala Muthu* Department of Mathematics, Sathyabama Institute of Science and Technology, Tamilnadu, INDIA ABSTRACT This research work deals with the prediction of annual rainfall of Chennai city, India using Neural Network algorithm. Chennai is one of the metropolitan city in India where disaster management is in need of knowing the extreme precipitation in advance for the control of floods and droughts. For this purpose, the monthly rainfall of Chennai is modeled using the Neural Network algorithm. The experimental result shows that the proposed neural network algorithm gives better accuracy. The error measures indicate the proposed model’s performance accuracy. INTRODUCTION Rainfall prediction is one of the most important and challenging task carried over by meteorologists all over the world. Rainfall prediction is also useful for disaster management in tackling the extreme precipitations. KEY WORDS There are many forecasters doing lot of research to obtain more accuracy in the model they construct. There Chennai, rainfall, prediction, neural are many factors which affect rainfall prediction such as temperature, humidity, wind speed, pressure, dew network algorithm, error point etc. and hence prediction becomes more complicated for them since the real life data are nonlinear in measure nature. -

Chennai District

CHENNAI DISTRICT 1 CHENNAI DISTRICT 1. Introduction of about 5 km from the coast and attains a depth of about 63’. The two principal i) Geographical location of the currents, one from the north sets in about the district middle of October and continues till Chennai is situated in the North- February and another from the south flows Eastern end of Tamil Nadu on the coast of parallel to the coast, which starts during the Bay of Bengal. It lies between 12 o 9’ and early days of August and continues till the 13 o 9’ North and 80 o 12’ and 80 o 19’ East. middle of October. The total area of the district is 178.2 sq.km ii) Administrative profile It is bounded by the Bay of Bengal in the east and on the remaining three sides by Chennai City is one of the oldest Kancheepuram and Tiruvallur districts. The cities of India. Chennai district topography of the district is almost flat and encompasses the entire Chennai Corporation the ground level in the district slightly rises including 19 villages added in the year 1979 up to 22 ft above the mean sea level. from the Chengalpattu district. The Following table shows the administrative Chennai has a long beach, which profile of the district. stretches nearly 25.60 km from Thiruvottiyur in the north to Thiruvanmiyur in the south and it is sandy for about a km No. of from the shore. The bed of the sea is about Taluk Name Villages 42’ deep and slopes gradually for a distance Egmore - 13 Nungambakkam Mylapore - Triplicane 8 Mambalam - Guindy 15 Fort - Tondiarpet 7 Perambur- 12 Purasawakkam ii) Meteorological information Chennai has a tropical wet and dry climate. -

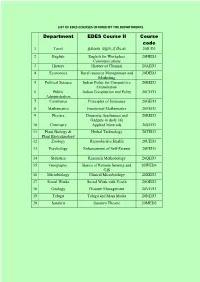

Department EDES Course II Course Code

LIST OF EDES COURSES OFFERED BY THE DEPARTMENTS Department EDES Course II Course code 1 Tamil தகவல் ெதாடர ்�யல் 20JED3 2 English English for Workplace 20HED3 Communications 3 History History of Chennai 20AED3 4 Economics Rural resource Management and 20DED3 Marketing 5 Political Science Indian Polity for Competitive 20BED3 Examination 6 Public Indian Constitution and Polity 20CED3 Administration 7 Commerce Principles of Insurance 20GED3 8 Mathematics Functional Mathematics 20PED3 9 Physics Domestic Appliances and 20RED3 Gadgets in daily life 10 Chemistry Applied Materials 20SED3 11 Plant Biology & Herbal Technology 20TED3 Plant Biotechnology 12 Zoology Reproductive Health 20UED3 13 Psychology Enhancement of Self-Esteem 20EED3 14 Statistics Research Methodology 20QED3 15 Geography Basics of Remote Sensing and 20WED3 GIS 16 Microbiology Clinical Microbiology 20XED3 17 Social Works Social Work with Youth 20OED3 18 Geology Disaster Management 20VED3 19 Telugu Telugu and Mass Media 20NED3 20 Sanskrit Sanskrit Theatre 20MED3 1) Department of Tamil Jiw rhuh ÉU¥g¥ ghl« - jftš bjhl®ãaš neh¡f« : • jftš bjhl®ã‹ ï‹¿aikahikia És§f it¤jš jftš bjhl®ò Kiwfis m¿a¢ brŒjš myF-1 bjhl®ò És¡f« : bjhl®ò v‹w brhšY¡F m¿P®fŸ jU« És¡f«- bjhl®ãaš v‹w brhšÈ‹ És¡f«. bjhl®ãaÈ‹ njh‰wK« ts®¢áí« :- g©il¡fhy« :- clyirî- xÈfŸ- thŒbkhÊ- F¿pLfŸ- ïir¡fUÉfŸ. brŒâ m¿É¡F« Kiw :- öJt®- x‰w®- XÉa«- gwit- br¥ngL- fšbt£L- T¤J- ehlf«- foj«- Ó£L¡fÉ kWky®¢á¡ fhy« :- m¢R« jhS«- Ä‹Åaš- bjhiy¡fh£á - bra‰if¡nfhŸ- fÂ¥bgh¿- g‹dh£L¢ brŒâ¤ bjhl®ò mik¥ò myF-2 m~¿iz¥ bghUŸfS« jftš bjhl®ò« :- nfhÊ- vW«ò- njÜ- fiuah‹- ehŒ- ahid- jhtu§fŸ. -

Database on Agasthyamalai Biosphere Reserve

Database on Agasthyamalai Biosphere Reserve Report submitted to Department of Environment, Tamil Nadu By D. Narasimhan & Sheeba J Irwin Centre for Floristic Research Department of Botany Madras Christian College (Autonomous) February 2017 0 CONTENT Sl. No Page No. 1. IN TRODUCTION 1 2. GEOGRAPHY/TOPOGRAPHY OF AGASTHYAMALAI BIOSPHERE RESERVE 3. PROTECTED AREAS WITHIN AGASTHYAMALAI BIOSPHERE RESERVE 4. FOREST TYPES IN AGASTHYAMALAI BIOSPHERE RESERVE 5. FLORA OF AGASTHYAMALAI BIOSPHERE RESERVE 6. FAUNA OF AGASTHYAMALAI BIOSPHERE RESERVE 7. ENDEMIC AND RED LISTED SPECIES IN AGASTHYAMALAI BIOSPHERE RESERVE 8. NATURAL RESOURCES OF AGASTHYAMALAI BIOSPHERE RESERVE 9. TRIBAL STATUS OFAGASTHYAMALAI BIOSPHERE RESERVE 10. THREATS FACED IN AGASTHYAMALAI BIOSPHERE RESERVE 11. CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT INITIATIVE TAKEN FOR CONSERVING AGASTHYAMALAI BIOSPHERE RESERVE 12. WAY FORWARD FOR EFFECTIVE CONSERVATION IN THE AGASTHYAMALAI BIOSPHERE RESERVE 13. REFERENCE 1 1. INTRODUCTION Recognizing the importance of Biosphere Reserves, The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) initiated an ecological programme called The Man and Biosphere (MAB) in 1972 . The Man and Biosphere (MAB) Programme is primarily aim ed at three fundamental principles , 1) Conservation of biodiversity, 2) Development of communities around biosphere reserve and 3) Support in research, environmenta l education and training. T he key criteria for a biosphere reserve reiterate that the area should have a distinct core zone, buffer zone and a transition zone. MAB Programme emphasize s research on conserving the biodiversity and sustainable use of its components for the development of communities around biosphere reserve ( www.unesco.org; Schaaf, 2002). MAB Programme largely assists the traditional societies living within and around the Biosphere Reserve (BR) , who are rich in Traditional Ecological Knowledge for facilitating their participation in the management of Biosphere Reserve ( Ramakrishnan, 2002). -

Srm Journal of Business Horizon

SRM JOURNAL OF BUSINESS HORIZON November 2020 Volume 7 Issue 1 ISSN : 2395-2504 AN ANNUAL PUBLICATION OF DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE College of Science and Humanities SRM Institute of Science and Technology Kattankulathur, Tamilnadu 603-203 -India MESSAGE FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK “Performance leads to recognition. Recognition brings respect. Respect enhances power. Humility and grace in one’s moments of power enhances dignity of an organization.” -N.R. Narayana Murthy, Founder of Infosys “If you do build a great experience, customers tell each other about that. Word of mouth is very powerful.” - Jeff Bezos, CEO and Founder of Amazon It gives us great pleasure in introducing the 7th volume of SRM Journal of Business Horizon. The Department of Commerce is a well known for its academic excellence and dedicated approach towards dissemination of knowledge. The commerce department appreciates the role of research in business and is committed to developing an inclination towards research in both faculty and students. In this pursuit, the department has taken the initiative to release the 7th Volume of SRM Journal of Business Horizon to encourage students and research scholars to publish their research articles. It will be an add-on to the enriched catalogue of college publications and academic literature. It aims at promoting research in the areas of business, management, economics, finance and governance and encourages empirical and inductive writings. The journal provides the scope to promote research publications among academicians, researchers, policy makers and practitioners. It publishes research articles relevant for national and international significance. Research is an enduring field with persistent and focused efforts lead to positive results. -

Indian Meteorological Society, Chennai Chapter Newsletter Vol.19, Issue No.2, Dec 2019 and Vol.20, Issue No.1, May 2020 EDIT

Indian Meteorological Society, Chennai Chapter Newsletter Vol.19, Issue No.2, Dec 2019 and Vol.20, Issue No.1, May 2020 EDITORIAL BOARD Editor : Dr. B. Amudha Members : Dr. N. Jayanthi, Dr. Y.E.A. Raj and Dr. B. Geetha BREEZE Vol.19(2) and Vol.20 (1) May 2020 CONTENTS No. Title of the Article Author Page No. 1. Chennai Region - Rainfall Climatology Y.E.A. Raj 6 and Recent Rainfall Trends 2. Monitoring Landslides from Satellites Manoj Kumar Thakur 13 T.V. Lakshmi Kumar A. Naga Rajesh and M.S. Narayanan 3. South West Monsoon - 2019 N. Puviarasan 16 4. Melody of South West Monsoon - 2019 S. Sivakumar 18 5. Psychological Heat Wave? S. Raghavan 19 6. A Tribute to (late) Shri. S.Raghavan Y.E.A. Raj 22 (1932 – 2020) 7. A Humble Tribute to (late) Shri.S.Raghavan N. Jayanthi 27 8. கண்ணீர் அஞ்ச쮿 – 29 Tearful Tribute to Late Shri. S.Raghavan R. Suresh 9. Book Review – N. Selvam 40 10. Seminar on Monsoons – 2019 : Photographs 43 11. Obituary : Shri. S. Raghavan 44 - Bio data 45 - Honour Plaque 46 - Photos Collage 47 12. In the Winds of Time 50 Disclaimer: The Editor and IMS Chennai Chapter are not responsible for the views expressed by the authors. 2 BREEZE Vol.19(2) and Vol.20 (1) May 2020 From the Chairman’s Desk…... Dear members of IMS Chennai Chapter and readers of BREEZE, The current issue of BREEZE is a combined one of December 2019 & May 2020 (Vol. 19, Issue 2 & Vol 20, Issue 1) with usual technical notes from members.