Society for Industrial Archeology Guidebook to Chicago

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Onechundrecl Rjcarr Ofrailroading

189,6 '''19126 OnecHundrecl Rjcarr ofRailroading By CHARLES FREDERICK CARTER Author of "When Railroads Were New," "Big Railroading," etc.. The New York Central Railroad 0 e4 a 50 50 -0 •;37, .2 —c4 bt aou• C 74-4 ••••;:;. -5 ••• X '7' te: I t 1,4 a P. Le on. E >• ;:rc .c g 7," U E 1-, 100 Y.EAlk_S OF SErk_NTICE Y an interesting coincidence the ses- quicentennial anniversary of the United States and the centennial an- niversary of the New York Central Railroad fall in the same year. Just as the United States was the first true republic to endure and now has be- come the greatest republic the world has ever known, so the New York Central, one of the first important railroads to be established in America, has grown into a great transporta- tion system which, if it is not the foremost in the world, is at least among the very few in the front rank. In the development of the nation the New York Central Railroad has played an essential part. It became the principal highway over which flowed the stream of emigration to people the West, and it has remained the favorite ave- nue of communication between East and West for the descendants of these pioneer emigrants. Keeping pace with the demands upon it for transportation, the New York Central has de- veloped into a railroad system now known as The New York Central Lines, which moves about ten per cent of the aggregate amount of freight hauled by all the railroads as Measured in ton-miles, that is, one ton hauled one mile, 3 NEW Y-0 P.,K_ CENTELAL LIN ES ••• 04101110"r.- Grand Central Terminal, New York City, as it appears from Forty -second Street. -

Planners Guide to Chicago 2013

Planners Guide to Chicago 2013 2013 Lake Baha’i Glenview 41 Wilmette Temple Central Old 14 45 Orchard Northwestern 294 Waukegan Golf Univ 58 Milwaukee Sheridan Golf Morton Mill Grove 32 C O N T E N T S Dempster Skokie Dempster Evanston Des Main 2 Getting Around Plaines Asbury Skokie Oakton Northwest Hwy 4 Near the Hotels 94 90 Ridge Crawford 6 Loop Walking Tour Allstate McCormick Touhy Arena Lincolnwood 41 Town Center Pratt Park Lincoln 14 Chinatown Ridge Loyola Devon Univ 16 Hyde Park Peterson 14 20 Lincoln Square Bryn Mawr Northeastern O’Hare 171 Illinois Univ Clark 22 Old Town International Foster 32 Airport North Park Univ Harwood Lawrence 32 Ashland 24 Pilsen Heights 20 32 41 Norridge Montrose 26 Printers Row Irving Park Bensenville 32 Lake Shore Dr 28 UIC and Taylor St Addison Western Forest Preserve 32 Wrigley Field 30 Wicker Park–Bucktown Cumberland Harlem Narragansett Central Cicero Oak Park Austin Laramie Belmont Elston Clybourn Grand 43 Broadway Diversey Pulaski 32 Other Places to Explore Franklin Grand Fullerton 3032 DePaul Park Milwaukee Univ Lincoln 36 Chicago Planning Armitage Park Zoo Timeline Kedzie 32 North 64 California 22 Maywood Grand 44 Conference Sponsors Lake 50 30 Park Division 3032 Water Elmhurst Halsted Tower Oak Chicago Damen Place 32 Park Navy Butterfield Lake 4 Pier 1st Madison United Center 6 290 56 Illinois 26 Roosevelt Medical Hines VA District 28 Soldier Medical Ogden Field Center Cicero 32 Cermak 24 Michigan McCormick 88 14 Berwyn Place 45 31st Central Park 32 Riverside Illinois Brookfield Archer 35th -

Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the National Archives

REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 116 Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the national archives 1 Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the National Archives REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 116 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC Compiled by Peter F. Brauer 2010 United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Records relating to railroads in the cartographic section of the National Archives / compiled by Peter F. Brauer.— Washington, DC : National Archives and Records Administration, 2010. p. ; cm.— (Reference information paper ; no 116) includes index. 1. United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Cartographic and Architectural Branch — Catalogs. 2. Railroads — United States — Armed Forces — History —Sources. 3. United States — Maps — Bibliography — Catalogs. I. Brauer, Peter F. II. Title. Cover: A section of a topographic quadrangle map produced by the U.S. Geological Survey showing the Union Pacific Railroad’s Bailey Yard in North Platte, Nebraska, 1983. The Bailey Yard is the largest railroad classification yard in the world. Maps like this one are useful in identifying the locations and names of railroads throughout the United States from the late 19th into the 21st century. (Topographic Quadrangle Maps—1:24,000, NE-North Platte West, 1983, Record Group 57) table of contents Preface vii PART I INTRODUCTION ix Origins of Railroad Records ix Selection Criteria xii Using This Guide xiii Researching the Records xiii Guides to Records xiv Related -

Annual Taxpayer Location Address List 2014

Annual Taxpayer Location Address List 2014 ILLINOIS BUSINESS TAX NUMBER SEQUENCE NUMBER TYPE OF FILER 4139-6499 0 CL 4152-9510 0 CL 4148-4207 0 CL 4044-1474 0 CL 0196-7053 0 CL 2241-7494 1 CL 4149-4229 0 CL 3904-2121 0 CL 3041-2331 0 CL Page 1 of 3815 09/27/2021 Annual Taxpayer Location Address List 2014 SIC DBA NAME OWNING ENTITY 5431 JACKIE BURNS 5947 KENSON ORR 5999 SHANNON WYNN BITE A BILLION 5947 MADELINE RAMOS KAY-EMI BALLOON KEEPSAKES 2038 SCHWANS HOME SERVICE INC 5065 ECHOSPHERE LLC 5947 AFRICOBRA LLC 5999 CHASE EVENTS INC 5661 VICTOR GUTIERREZ Page 2 of 3815 09/27/2021 Annual Taxpayer Location Address List 2014 ADDRESS ADDRESS SECONDARY CITY PO BOX 25 MARSHALL PO BOX 6623 ENGLEWOOD 316 PINE ST SUMTER 3N265 WILSON ST ELMHURST 5233 W 29TH PL CICERO Page 3 of 3815 09/27/2021 Annual Taxpayer Location Address List 2014 Boundaries - Community STATE ZIP LOCATION ZIP Codes Areas MN 56258-0025 PO BOX 25 MARSHALL, MN 56258-0025 (44.44589741800007, - 95.78116775399997) CO 80155-6623 PO BOX 6623 ENGLEWOOD, CO 80155-6623 (39.592180549000034, - 104.87610010699996) SC 29150-3545 316 PINE ST SUMTER, SC 29150-3545 (33.93458485700006, - 80.34958253299999) IL 60126-1359 3N265 WILSON ST ELMHURST, IL 60126-1359 (41.92621464400003, - 87.93331031799994) IL 60804-3523 5233 W 29TH PL CICERO, IL 60804-3523 Page 4 of 3815 09/27/2021 Annual Taxpayer Location Address List 2014 Historical Zip Codes Census Tracts Wards Wards 2003- 2015 21432 20300 12955 15603 4458 Page 5 of 3815 09/27/2021 Annual Taxpayer Location Address List 2014 4144-6917 0 CL 4114-7601 0 CL 2258-3394 0 CL 2251-1423 0 CL 0354-2785 0 CL 4002-5845 0 CL Page 6 of 3815 09/27/2021 Annual Taxpayer Location Address List 2014 5999 JASCO INC 5651 CORTEZ BROADNAX 2449 THE LONGABERGER CO 7379 DUNN SOLUTIONS GROUP INC 2099 LANDSHIRE INC 1389 IPC (USA) INC. -

Rainready Calumet Corridor, IL Plan

RainReady Calumet Corridor, IL Plan RainReady Calumet Corridor, IL Plan PREPARED BY THE CENTER FOR NEIGHBORHOOD TECHNOLOGY AND THE U.S. ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS MARCH 2017 ©2017 CENTER FOR NEIGHBORHOOD TECHNOLOGY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 VILLAGE OF ROBBINS Purpose of the RainReady Plan 1 A Citizen’s Guide to a RainReady Robbins i The Problem 2 The Path Ahead 3 VILLAGE OF ROBBINS How to Use This Plan 4 COMMUNITY SNAPSHOT 1 INTRODUCTION 5 ROBBINS, IL AT A GLANCE 2 The Vision 5 Flooding Risks and Resilience Opportunities 3 THE PROBLEM 6 RAINREADY ROBBINS COMMUNITY SURVEY 8 CAUSES AND IMPACTS OF URBAN FLOODING 10 EXISTING CONDITIONS IN ROBBINS, IL Your Homes and Neighborhoods 10 THE PATH FORWARD 23 Your Business Districts and Shopping Centers 12 What Can We Do? 23 Your Industrial Centers and How to Approach Financing Transportation Corridors 14 RainReady Communities 26 Your Open Space and Natural Areas 16 Community Assets 18 PARTNERS AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 29 Steering Committees 30 COMMUNITY PRIORITIES 20 Technical Advisory Committee 33 Non-TAC Advisors 33 RAINREADY ACTION PLAN 22 THE PLANNING PROCESS 34 Purpose of the RainReady Plan 34 RAINREADY ROBBINS IMPLEMENTATION PLAN Planning and Outreach Approach 36 Goal 1: Reorient 24 Goal 2: Repair 28 REGIONAL CONTEXT 42 Goal 3: Retrofit 31 RAINREADY: REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT SUMMARY 50 RAINREADY SOLUTIONS GOALS, STRATEGIES, AND ACTIONS 55 A RainReady Future is Possible! 55 RAINREADY GOALS 56 The Three R’s: Reorient, Repair, Retrofit 56 THE THREE R’S 61 GOALS, STRATEGIES, AND ACTIONS 62 Goal 1: Reorient 64 Goal 2: Repair 66 Goal 3: Retrofit 67 RAINREADY CALUMET CORRIDOR PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Purpose of the RainReady Plan From more intense storms and chronic urban flooding to economic constraints and aging infrastructure, communities across the nation must find ways to thrive in the midst of shocks and stresses. -

Conceived by America's Labor Unions As a Testament to Their Cause, The

Conceived by America’s labor unions as a testament to their cause, the legislation sanctioning the holiday was shepherded through Congress amid labor unrest and signed by President Grover Cleveland as a reluctant election-year compromise. Pullman, Illinois, was a company town, founded in 1880 by George Pullman, president of the railroad sleeping car company. Pullman designed and built the town to stand as a utopian workers’ community insulated from the moral (and political) seductions of nearby Chicago. The town was srictly, almost feudally, organized: row houses for the assembly and craft workers; modest Victorians for the managers; and a luxurious hotel where Pullman himself lived and where visiting customers, suppliers, and salesman would lodge while in town. Its residents all worked for the Pullman Company, their paychecks drawn from Pullman bank, and their rent, set by Pullman, deducted automatically from their weekly paychecks. The town, and the company, operated smoothly and successfully for more than a decade. But in 1893, the Pullman Company was caught in the nationwide economic depression. Orders for railroad sleeping cars declined, and George Pullman was forced to lay off hundreds of employees. Those who remained endured wage cuts, even while rents in Pullman remained consistent. Take-home paychecks plummeted. And so the employees walked out, demanding lower rents and higher pay. The American Railway Union, led by a young Eugene V. Debs, came to the cause of the striking workers, and railroad workers across the nation boycotted trains carrying Pullman cars. Rioting, pillaging, and burning of railroad cars soon ensued; mobs of non-union workers joined in. -

The Pullman Strike

Using Context and Subtext to Understand the Pullman Rail Strike of 1894 Bruce A. Lesh Franklin High School Reisterstown, Maryland Learning to Think Historically: A Tool for Attacking Historical Sources Text: What is visible/readable--what information is provided by the source? Context: What was going on during the time period? What background information do you have that helps explain the information found in the source? Subtext: What is between the lines? Must ask questions about: Author: Who created the source and what do we know about that person? Audience: For whom was the source created? Reason: Why was this source produced at the time it was produced? I do solemnly swear that my testimony will be based on the perspective of my source, nothing but the perspective of my source, even if it has an overt point- of-view, so help my first quarter grade. Directions for Congressional Hearing • Each team will testify in front of Congress • All team members will be asked questions • Testimony must be based on information found in your source • Members of Congress (everyone in the audience) must take notes on the testimony • Hearing must determine: – Who was at fault and why? – Were the president’s actions constitutionally justiEied? – Was Eugene Debs justly accused? – What lessons about the relationship between labor and management can be learned from the Pullman situation? George Pullman Pullman Railcars (Sleepers) Interior of Pullman Sleeper Cars Pullman, Illinois Main Street Pullman, Illinois Center Square, Pullman HPC1_81 Workers Homes—Pullman Pullman Axel Workers Depression of 1893 • 18% unemployment • 25% of urban workers • 1/3rd of manufacturing jobs • 1/10 banks close • 25% of railroads shut down • 50% drop in railroad construction • Pullman cuts wages for his workers by 25% Eugene V. -

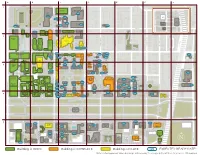

Building Is OPEN Building Is COMPLETE Building Is IN-USE

A B C D E F G E 55TH ST E 55TH ST 1 Campus North Parking Campus North Residential Commons E 52ND ST The Frank and Laura Baker Dining Commons Ratner Stagg Field Athletics Center 5501-25 Ellis Offices - TBD - - TBD - Park Lake S AUG 15 S HARPER AVE Court Cochrane-Woods AUG 15 Art Center Theatre AVE S BLACKSTONE Harper 1452 E. 53rd Court AUG 15 Henry Crown Polsky Ex. Smart Field House - TBD - Alumni Stagg Field Young AUG 15 Museum House - TBD - AUG 15 Building Memorial E 53RD ST E 56TH ST E 56TH ST 1463 E. 53rd Polsky Ex. 5601 S. High Bay West Campus Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Cottage (2021) Utility Plant AUG 15 Michelson High (West) Energy (Central) (East) 55th, 56th, 57th St Grove Center for Metra Station Physics Physics Child Development TAAC 2 Center - Drexel Accelerator Building Medical Campus Parking B Knapp Knapp Medical Regenstein Library Center for Research William Eckhardt Biomedical Building AVE S KENWOOD Donnelley Research Mansueto Discovery Library Bartlett BSLC Center Commons S Lake Park S MARYLAND AVE S MARYLAND S DREXEL BLVD AVE S DORCHESTER AVE S BLACKSTONE S KIMBARK AVE S UNIVERSITY AVE AVE S WOODLAWN S ELLIS AVE Bixler Park Pritzker Need two weeks to transition School of Biopsychological Medicine Research Building E 57TH ST E 57TH ST - TBD - Rohr Chabad Neubauer Collegium- TBD - Center for Care and Discovery Gordon Center for Kersten Anatomy Center - TBD - Integrative Science Physics Hitchcock Hall Cobb Zoology Hutchinson Quadrangle - TBD - Gate Club Institute of- PoliticsTBD - Snell -

Railroad Postcards Collection 1995.229

Railroad postcards collection 1995.229 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Audiovisual Collections PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Railroad postcards collection 1995.229 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 4 Historical Note ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Railroad stations .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Alabama ................................................................................................................................................... -

Cta 2016 Historical Calendar Cta 2016 January

cta 2016 Historical Calendar cta 2016 January Chicago Motor Coach Company (CMC) bus #434, manufactured by the Ford Motor Company, was part of a fleet of buses operated by the Chicago Motor Coach Company, one of the predecessor transit companies that were eventually assimilated into the Chicago Transit Authority. The CMC originally operated buses exclusively on the various park boulevards in Chicago, and became known by the marketing slogan, “The Boulevard Route.” Later, service was expanded to operate on some regular streets not served by the Chicago Surface Lines, particularly on the fringes of the city. Chicagoans truly wanted a unified transit system, and it was for this reason that the Chicago Transit Authority was established by charter in 1945. The CMC was not one of the initial properties purchased that made up CTA’s inaugural services on October 1, 1947; however, it was bought by CTA in 1952. D E SABCDEFG: MDecember 2015 T February 2016 W T F S CTA Operations Division S M T W T F S S M T W T F S Group Days Off 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 t Alternate day off if you 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 work on this day 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 l Central offices closed 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 27 28 29 30 31 28 29 1New Year’s Day 2 E F G A B C D 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 D E F G A B C 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 C D E F G A B 17 18Martin Luther King, Jr. -

February 2021 a Publication of the Old Irving Park Association By, for and About People Living in the Neighborhood

Old Irving Park NEWS FEBRUARY a VOLUME 35 | ISSUE 1 | 2021 OLD IRVING PARK NEWS | Volume 35 a Issue 1 a February 2021 A publication of the Old Irving Park Association by, for and about people living in the neighborhood. Old Irving Park neighborhood boundaries includes: Addison on the south, Montrose on the north, Pulaski on the east and the Milwaukee District North Line on the west (from Addison to Irving Park) continuing with the freight/Amtrak railroad tracks from Irving Park to Montrose (i.e., east of Knox Ave.). A map can be found on our website. [email protected] www.oldirvingpark.com The Old Irving Park Association (OIPA) is a non-profit, all volunteer community group active FB: oldirvingparkassoc since 1983. The Old Irving Park News is published ten times a year. Delivery Staff President Vice President A note about the advertisement Devin, Owen & Asha Alexander Adrienne Chan Annie Swingen featured in this issue. Lynn Ankney Julian Arias Secretary Treasurer As the Phases to open Chicago occur, check with Bridget Bauman Bart Goldberg Lynn Ankney the individual advertiser by calling or visiting Sandra Broderick their website for information on their status. Barbara Chadwick Board of Directors Gayle Christensen Michael Cannon Adrian & Oliver Christiansen Colleen Kenny TABLE OF CONTENTS Barbara Cohn Scott Legan Message From the Board .............................2 Mary Czarnowski Merry Marwig OIPA Board Meeting Report .......................... 4 David Evaskus Meredith O’Sullivan OIP Anniversaries & Birthdays .....................8 Irene Flaherty OIP Real Estate Activity ............................... 10 Bart Goldberg Street Banners Sharon Graham Adrienne Chan Message From a Neighbor ......................... 12 Julia Henriques Irving Park Garden Club ............................. -

• CORA REVISION: AMTRAK Amtrak Chicago Terminal CORA Revision AMTK 05-01 Effective February 18, 2005

THE BELT RAILWAY COMPANY OF CHICAGO Office of General Manager Transportation May 31, 2006 Notice No. 4 **In Effect 12:01 AM – June 1, 2006** TO ALL CONCERNED: All Notices issued from January 1, 2004 through June 1, 2006, are hereby canceled PURPOSE of REVISION Cancellation of previous notices.2006 notices will be issued by the following categories 1. General Notices 2. Hump/Yard 3. Industry 4. CORA Update Only one notice in each category will be in effect at a time Changes, amendments will note the purpose for the change and identify new items, additions and revisions to existing notices. • CORA REVISION: AMTRAK Amtrak Chicago Terminal CORA Revision AMTK 05-01 Effective February 18, 2005 As of 10:01 PM Friday, February 18, 2005, control of the 21st Street Interlocking is transferred to the Lumber Street Train Director. As a result of this transfer, make the following changes to the Amtrak Section of the CORA Guide: 1. Page AMTK-2, GCOR 9.24 Signal Equipment: Use of tower horn discontinued. Section deleted in its entirety. 2. Page AMTK-2, General Timetable Instructions: Under “Radios”, change listing for channel 46-46 to read “Lumber Street Train Director.” Under “Telephone Numbers”, delete listing for 21st Street Train Director. 3. Page AMTK-5, 21st Street Interlocking: Change reference to “21st Street Train Director” to read “Lumber Street Train Director”. 4. Page AMTK-7, Map of Freight Route through Amtrak 21st Street and Lumber Street Interlockings: Northward and Southward interlocking signals on opposite sides of Lumber Street road crossing have been transposed, i.e., the Northward signals are now on the SOUTH side of the crossing and the Southward signals are now on the NORTH side of the crossing.