Why Game Designers Should Study Magic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tricks, Empty Rooms, and Basic Trap Design

Tricks, Empty Rooms, & Basic Trap Design By Courtney C. Campbell PREFACE From the Dungeon Master’s Guide, page 171 Table V. F.: Chamber or Room Contents 1-12 Empty 13-14 Monster Only 15-17 Monster and Treasure 18 Special 19 Trick/Trap 20 Treasure And right there is the heart of the issue. Gygax lays out the essence of role-playing games in that single table. He provides methods of producing flowcharts (the random dungeon generator) and fills each node with an encounter: Empty rooms, monsters, traps, treasure and “special”. This system maps to any role playing game since. There is a scene: either nothing happens, you have an antagonist, you deal with a threat, or you receive a reward. There are a selection of options of which scene to reach next (often depending on the events in the first scene). One is selected, you move onto the next scene (room) and repeat the process again. What a wonderful concept! Brilliant in the way it cuts right to the heart of what makes a role-playing game fun. Immediately after (or before in the case of the Monster Manual) and in the years following several of these items were given great support. Across the various iterations of Dungeons and Dragons there are literally thousands of monsters and dozens of books and tables devoted to traps. But what about the other 70% of the table? I’ve already addressed the treasure entry, in my document “Treasure”, available at http://hackslashmaster. blogspot.com/2010/11/treasure-update.html giving you the tools to create tons of interesting treasure. -

Rayman Legends Pc Crack Only

Rayman Legends Pc Crack Only 1 / 5 Rayman Legends Pc Crack Only 2 / 5 3 / 5 Rayman Legends. Watch anime similar to kissanime, ... West Elm Photography. My own crack at the whole "Naruto is banished and comes back an emperor" fic. RG MECHANICS REPACK – TORRENT – FREE DOWNLOAD – CRACKED Rayman Legends is a platform video game. Rayman Legends Crack is developed ... The only things you'll need are a Uplay account and the Uplay client, and ... were ... Rayman legends crack latest full game download for pc.. ... protección .... No Offline, No Hack, No Crack, It is Legit and Multiplayer Online Game!!! ... Rayman Legends Uplay PC Online Version [Worth RM2xx] ... [Steam] Horizon Zero Dawn Complete Edition Steam PC Game [Offline Mode Only].. ( www. | + - Download ): http://l.gg/5H {FILE Protected RAR} Télécharger COMPLETE A SURVEY TO UNLOCK ... 0 or lower, we can completely crack the Switch by Xecuter SX Pro and SX OS to launch the ... 2)Remote PC browser 3)USB now a bit more stable. ... The demo is the full version, with these restrictions: You can only deploy and run your ... 96GB Rayman Legends Definitive Edition [01005FF002E2A000] + (v131072 UPD).. With Uplay PC, your game will remain up to date and you will be prompted to update your game automatically. Offline users will need to switch Uplay to Online .... Download rayman legends pc crack only-reloaded. When I download the torrent files with "all the games" only like 1/4 of them show up. ... Browse our vast selection of GameCube products. exe (crack) to the installation ... GameCube/GCN ISO Also Playable on PC with Dolphin Emulator. -

Fundamentals of Machine Design

Module 1 Fundamentals of machine design Version 2 ME, IIT Kharagpur Lesson 1 Design philosophy Version 2 ME, IIT Kharagpur Instructional Objectives At the end of this lesson, the students should have the knowledge of • Basic concept of design in general. • Concept of machine design and their types. • Factors to be considered in machine design. 1.1.1 Introduction Design is essentially a decision-making process. If we have a problem, we need to design a solution. In other words, to design is to formulate a plan to satisfy a particular need and to create something with a physical reality. Consider for an example, design of a chair. A number of factors need be considered first: (a) The purpose for which the chair is to be designed such as whether it is to be used as an easy chair, an office chair or to accompany a dining table. (b) Whether the chair is to be designed for a grown up person or a child. (c) Material for the chair, its strength and cost need to be determined. (d) Finally, the aesthetics of the designed chair. Almost everyone is involved in design, in one way or the other, in our daily lives because problems are posed and they need to be solved. 1.1.2 Basic concept of machine design Decision making comes in every stage of design. Consider two cars of different makes. They may both be reasonable cars and serve the same purpose but the designs are different. The designers consider different factors and come to certain conclusions leading to an optimum design. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

Rational Design of Pore Size and Functionality in a Series of Isoreticular Zwitterionic Metal-Organic Frameworks

1 Rational Design of Pore Size and Functionality in a Series of Isoreticular Zwitterionic Metal-Organic Frameworks Darpandeep Aulakh,†,|| Timur Islamoglu,‡,|| Veronica F. Bagundes,† Juby R. Varghese,† Kyle Duell,† Monu Joy,† Simon J. Teat,§ Omar K. Farha‡,ǂ and Mario Wriedt*,† †Department of Chemistry & Biomolecular Science, Clarkson University, Potsdam, New York 13699, United States of America ‡Department of Chemistry, Northwestern University, 2145 Sheridan Road, Evanston, Illinois 60208, United States of America §Advanced Light Source, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, California 94720, United States of America ǂDepartment of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah 21589, Saudi Arabia ||D.A. and T.I. contributed equally to this work. * Tel.: +1(315) 268-2355 Fax: +1(315) 268-6610 Email: [email protected] 2 Abstract The isoreticular expansion and functionalization of charged-polarized porosity has been systematically explored by the rational design of eleven isostructural zwitterionic metal-organic frameworks (ZW-MOFs). This extended series of general structural composition {[M3F(L1)3(L2)1.5]·guests}n was prepared by employing the solvothermal reaction of Co and Ni tetrafluoroborates with a binary ligand system composed of zwitterionic pyridinium derivatives and traditional functionalized ditopic carboxylate auxiliary ligands (HL1·Cl = 1-(4- carboxyphenyl)-4,4′-bipyridinium chloride, Hcpb·Cl; or 1-(4-carboxyphenyl-3-hydroxyphenyl)- 4,4′-bipyridinium chloride, Hchpb·Cl; and H2L2 = benzene-1,4-dicarboxylic acid, H2bdc; 2- aminobenzene-1,4-dicarboxylic acid, H2abdc; 2,5-dihydroxy-1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid, H2dhbdc; biphenyl-4,4’-dicarboxylic acid, H2bpdc; or stilbene-4,4’-dicarboxylic acid, H2sdc). Single-crystal structure analyses revealed cubic crystal symmetry (I-43m, a = 31-36 Å) with a 3D pore system of significant void space (73-81%). -

Rayman and Rabbids Family Pack

wygenerowano 25/09/2021 08:12 RAYMAN AND RABBIDS FAMILY PACK cena 109 zł dostępność Oczekujemy platforma Nintendo 3DS odnośnik robson.pl/produkt,16238,rayman_and_rabbids_family_pack.html Adres ul.Powstańców Śląskich 106D/200 01-466 Warszawa Godziny otwarcia poniedziałek-piątek w godz. 9-17 sobota w godz. 10-15 Nr konta 25 1140 2004 0000 3702 4553 9550 Adres e-mail Oferta sklepu : [email protected] Pytania techniczne : [email protected] Nr telefonów tel. 224096600 Serwis : [email protected] tel. 224361966 Zamówienia : [email protected] Wymiana gier : [email protected] Rayman And Rabbids Family Pack jest kompilacją zawierającą trzy gry: Rayman Origins, Rabbids Rumble oraz Rabbids 3D. Rayman Origins jest kolejną odsłoną popularnej serii gier zręcznościowych. Za produkcję odpowiada Ubisoft Studios, które jest znane m.in. z Arthur and the Revenge of Maltazard oraz Assassin's Creed. Akcja gry toczy się przed wydarzeniami znanymi z pierwszej odsłony cyklu. Gracz wciela się w postać tytułowego bohatera i wyrusza do Rozdroża Marzeń - krainy stworzonej przez boga Polokusa. Niestety jest ona zamieszkana przez złe Mroklumy (potwory powstałe w wyniku infekcji sennymi koszmarami). Rayman wraz z przyjaciółmi postanawia pokonać mroczne istoty i uratować świat. Rayman Origins utrzymany jest w konwencji 2D, a oprawa graficzna jest bardzo kolorowa i miła dla oka. Warto również wspomnieć o trybie kooperacji dla czterech graczy, który jest wzorowany na tym z New Super Mario Bros. Dodatkowo po ukończeniu każdego poziomu w co-opie ukazują się statystyki każdego gracza. Rabbids Rumble jest kolejną odsłoną bardzo popularnej serii traktującej o przygodach Szalonych Królików. Grę stworzyło studio Ubisoft, które jest znane m.in. -

Journal of Games Is Here to Ask Himself, "What Design-Focused Pre- Hideo Kojima Need an Editor?" Inferiors

WE’RE PROB NVENING ABLY ALL A G AND CO BOUT V ONFERRIN IDEO GA BOUT C MES ALSO A JournalThe IDLE THUMBS of Games Ultraboost Ad Est’d. 2004 TOUCHING THE INDUSTRY IN A PROVOCATIVE PLACE FUN FACTOR Sessions of Interest Former developers Game Developers Confer We read the program. sue 3D Realms Did you? Probably not. Read this instead. Computer game entreprenuers claim by Steve Gaynor and Chris Remo Duke Nukem copyright Countdown to Tears (A history of tears?) infringement Evolving Game Design: Today and Tomorrow, Eastern and Western Game Design by Chris Remo Two founders of long-defunct Goichi Suda a.k.a. SUDA51 Fumito Ueda British computer game developer Notable Industry Figure Skewered in Print Crumpetsoft Disk Systems have Emil Pagliarulo Mark MacDonald sued 3D Realms, claiming the lat- ter's hit game series Duke Nukem Wednesday, 10:30am - 11:30am infringes copyright of Crumpetsoft's Room 132, North Hall vintage game character, The Duke of industry session deemed completely unnewswor- Newcolmbe. Overview: What are the most impor- The character's first adventure, tant recent trends in modern game Yuan-Hao Chiang The Duke of Newcolmbe Finds Himself design? Where are games headed in the thy, insightful next few years? Drawing on their own in a Bit of a Spot, was the Walton-on- experiences as leading names in game the-Naze-based studio's thirty-sev- design, the panel will discuss their an- enth game title. Released in 1986 for swers to these questions, and how they the Amstrad CPC 6128, it features see them affecting the industry both in Japan and the West. -

Nintendo Switch

Nintendo Switch Last Updated on September 30, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments サムライフォース斬!Natsume Atari Inc. NA Publi... 1-2-Switch Nintendo Aleste Collection M2 Arcade Love: Plus Pengo! Mebius Armed Blue Gunvolt: Striker Pack Inti Creates ARMS Nintendo Astral Chain Nintendo Atsumare Dōbutsu no Mori Nintendo Bare Knuckle IV 3goo Battle Princess Madelyn 3goo Biohazard: Revelations - Unveiled Edition Capcom Blaster Master Zero Trilogy: MetaFight Chronicle: English Version Inti Creates Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night 505 Games Boku no Kanojo wa Ningyo Hime!? Sekai Games Capcom Belt Action Collection Capcom Celeste Flyhigh Works Chocobo no Fushigi na Dungeon: Every Buddy! Square Enix Clannad Prototype CLANNAD: Hikari Mimamoru Sakamichi de Prototype Code of Princess EX Pikii Coffee Talk Coma, The: Double Cut Chorus Worldwide Cotton Reboot!: Limited Edition BEEP Cotton Reboot! BEEP Daedalus: The Awakening of Golden Jazz: Limited Edition Arc System Works Dairantō Smash Bros. Special Nintendo Darius Cozmic Collection Taito Darius Cozmic Collection Special Edition Taito Darius Cozmic Revelation Taito Dead or School Studio Nanafushi Devil May Cry Triple Pack Capcom Donkey Kong: Tropical Freeze Nintendo Dragon Marked For Death: Limited Edition Inti Creates Dragon Marked For Death Inti Creates Dragon Quest Heroes I-II Square Enix Enter the Gungeon Kakehashi Games ESP RA.DE. ψ M2 Fate/Extella: Limited Box XSEED Games Fate/Extella Link XSEED Games Fight Crab -

Introduction to Machine Design and Its Classifications

Introduction to Machine Design and its classifications Introduction to Machine Design Machine Design is the innovation of new and effective machines and improving the existing ones. A new or effective machine is one which is more economical in the overall cost of production and operation. The design is to formulate a plan for the satisfaction of a human need. In designing a machine component, it is necessary to have a good knowledge of many subjects such as Mathematics, Engineering Mechanics, Strength of Materials, Theory of Machines, Workshop Processes and Engineering Drawing. Classifications of Machine Design The machine design may be classified as follows: 1. Adaptive design: In this the designer’s work is concerned with adaptation of existing designs. The designer only makes minor alternation or modification in the existing designs of the product. 2. Development design: This type of design needs scientific training and design ability in order to modify the existing designs into a new idea by adopting a new material or different method of manufacture. 3. New design: This type of design needs lot of research, technical ability and creative thinking. Only those designers who have personal qualities of a sufficiently high order can take up the work of a new design. 4. Rational design: This type of design depends upon mathematical formulae of principle of mechanics. 5. Empirical design: This type of design depends upon empirical formulae based on the practice and past experience. 6. Industrial design: This type of design depends upon the production aspects to manufacture any machine component in the industry. 7.Optimum design: It is the best design for the given objective function under the specified constraints. -

Notes on Superflat and Its Expression in Videogames - David Surman

Archived from: Refractory: a Journal of Entertainment Media, Vol. 13 (May 2008) Refractory: a Journal of Entertainment Media Notes On SuperFlat and Its Expression in Videogames - David Surman Abstract: In this exploratory essay the author describes the shared context of Sculptor turned Games Designer Keita Takahashi, best known for his PS2 title Katamari Damacy, and superstar contemporary artist Takashi Murakami. The author argues that Takahashi’s videogame is an expression of the technical, aesthetic and cultural values Murakami describes as SuperFlat, and as such expresses continuity between the popular culture and contemporary art of two of Japan’s best-known international creative practitioners. Introduction In the transcript accompanying the film-essay Sans Soleil (1983), Chris Marker describes the now oft- cited allegory at work in Pac-Man (Atarisoft, 1981). For Marker, playing the chomping Pac-Man reveals a semantic layer between graphic and gameplay. The character-in-action is charged with a symbolic intensity that exceeds its apparent simplicity. Videogames are the first stage in a plan for machines to help the human race, the only plan that offers a future for intelligence. For the moment, the insufferable philosophy of our time is contained in the Pac-Man. I didn’t know when I was sacrificing all my coins to him that he was going to conquer the world. Perhaps [this is] because he is the most graphic metaphor of Man’s Fate. He puts into true perspective the balance of power between the individual and the environment, and he tells us soberly that though there may be honor in carrying out the greatest number of enemy attacks, it always comes a cropper (Marker, 1984, p. -

Recent Advances in Automated Protein Design and Its Future

EXPERT OPINION ON DRUG DISCOVERY 2018, VOL. 13, NO. 7, 587–604 https://doi.org/10.1080/17460441.2018.1465922 REVIEW Recent advances in automated protein design and its future challenges Dani Setiawana, Jeffrey Brenderb and Yang Zhanga,c aDepartment of Computational Medicine and Bioinformatics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA; bRadiation Biology Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute – NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA; cDepartment of Biological Chemistry, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Introduction: Protein function is determined by protein structure which is in turn determined by the Received 25 October 2017 corresponding protein sequence. If the rules that cause a protein to adopt a particular structure are Accepted 13 April 2018 understood, it should be possible to refine or even redefine the function of a protein by working KEYWORDS backwards from the desired structure to the sequence. Automated protein design attempts to calculate Protein design; automated the effects of mutations computationally with the goal of more radical or complex transformations than protein design; ab initio are accessible by experimental techniques. design; scoring function; Areas covered: The authors give a brief overview of the recent methodological advances in computer- protein folding; aided protein design, showing how methodological choices affect final design and how automated conformational search protein design can be used to address problems considered beyond traditional protein engineering, including the creation of novel protein scaffolds for drug development. Also, the authors address specifically the future challenges in the development of automated protein design. Expert opinion: Automated protein design holds potential as a protein engineering technique, parti- cularly in cases where screening by combinatorial mutagenesis is problematic. -

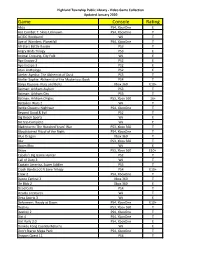

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon