Running Head: SOUTHEAST SASKATCHEWAN FLOODING in 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saskatchewan Intraprovincial Miles

GREYHOUND CANADA PASSENGER FARE TARIFF AND SALES MANUAL GREYHOUND CANADA TRANSPORTATION ULC. SASKATCHEWAN INTRA-PROVINCIAL MILES The miles shown in Section 9 are to be used in connection with the Mileage Fare Tables in Section 6 of this Manual. If through miles between origin and destination are not published, miles will be constructed via the route traveled, using miles in Section 9. Section 9 is divided into 8 sections as follows: Section 9 Inter-Provincial Mileage Section 9ab Alberta Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9bc British Columbia Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9mb Manitoba Intra-Provincial Mileage Section9on Ontario Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9pq Quebec Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9sk Saskatchewan Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9yt Yukon Territory Intra-Provincial Mileage NOTE: Always quote and sell the lowest applicable fare to the passenger. Please check Section 7 - PROMOTIONAL FARES and Section 8 – CITY SPECIFIC REDUCED FARES first, for any promotional or reduced fares in effect that might result in a lower fare for the passenger. If there are none, then determine the miles and apply miles to the appropriate fare table. Tuesday, July 02, 2013 Page 9sk.1 of 29 GREYHOUND CANADA PASSENGER FARE TARIFF AND SALES MANUAL GREYHOUND CANADA TRANSPORTATION ULC. SASKATCHEWAN INTRA-PROVINCIAL MILES City Prv Miles City Prv Miles City Prv Miles BETWEEN ABBEY SK AND BETWEEN ALIDA SK AND BETWEEN ANEROID SK AND LANCER SK 8 STORTHOAKS SK 10 EASTEND SK 82 SHACKLETON SK 8 BETWEEN ALLAN SK AND HAZENMORE SK 8 SWIFT CURRENT SK 62 BETHUNE -

Saskatchewan Regional Newcomer Gateways

Saskatchewan Regional Newcomer Gateways Updated September 2011 Meadow Lake Big River Candle Lake St. Walburg Spiritwood Prince Nipawin Lloydminster wo Albert Carrot River Lashburn Shellbrook Birch Hills Maidstone L Melfort Hudson Bay Blaine Lake Kinistino Cut Knife North Duck ef Lake Wakaw Tisdale Unity Battleford Rosthern Cudworth Naicam Macklin Macklin Wilkie Humboldt Kelvington BiggarB Asquith Saskatoonn Watson Wadena N LuselandL Delisle Preeceville Allan Lanigan Foam Lake Dundurn Wynyard Canora Watrous Kindersley Rosetown Outlook Davidson Alsask Ituna Yorkton Legend Elrose Southey Cupar Regional FortAppelle Qu’Appelle Melville Newcomer Lumsden Esterhazy Indian Head Gateways Swift oo Herbert Caronport a Current Grenfell Communities Pense Regina Served Gull Lake Moose Moosomin Milestone Kipling (not all listed) Gravelbourg Jaw Maple Creek Wawota Routes Ponteix Weyburn Shaunavon Assiniboia Radwille Carlyle Oxbow Coronachc Regway Estevan Southeast Regional College 255 Spruce Drive Estevan Estevan SK S4A 2V6 Phone: (306) 637-4920 Southeast Newcomer Services Fax: (306) 634-8060 Email: [email protected] Website: www.southeastnewcomer.com Alameda Gainsborough Minton Alida Gladmar North Portal Antler Glen Ewen North Weyburn Arcola Goodwater Oungre Beaubier Griffin Oxbow Bellegarde Halbrite Radville Benson Hazelwood Redvers Bienfait Heward Roche Percee Cannington Lake Kennedy Storthoaks Carievale Kenosee Lake Stoughton Carlyle Kipling Torquay Carnduff Kisbey Tribune Coalfields Lake Alma Trossachs Creelman Lampman Walpole Estevan -

Saskatchewan Conference Prayer Cycle

July 2 September 10 Carnduff Alida TV Saskatoon: Grace Westminster RB The Faith Formation Network hopes that Clavet RB Grenfell TV congregations and individuals will use this Coteau Hills (Beechy, Birsay, Gull Lake: Knox CH prayer cycle as a way to connect with other Lucky Lake) PP Regina: Heritage WA pastoral charges and ministries by including July 9 Ituna: Lakeside GS them in our weekly thoughts and prayers. Colleston, Steep Creek TA September 17 Craik (Craik, Holdfast, Penzance) WA Your local care facilities Take note of when your own pastoral July 16 Saskatoon: Grosvenor Park RB charge or ministry is included and remem- Colonsay RB Hudson Bay Larger Parish ber on that day the many others who are Crossroads (Govan, Semans, (Hudson Bay, Prairie River) TA holding you in their prayers. Raymore) GS Indian Head: St. Andrew’s TV Saskatchewan Crystal Springs TA Kamsack: Westminister GS This prayer cycle begins a week after July 23 September 24 Thanksgiving this year and ends the week Conference Spiritual Care Educator, Humboldt (Brithdir, Humboldt) RB of Thanksgiving in 2017. St. Paul’s Hospital RB Kelliher: St. Paul GS Prayer Cycle Crossroads United (Maryfield, Kennedy (Kennedy, Langbank) TV Every Pastoral Charge and Special Ministry Wawota) TV Kerrobert PP in Saskatchewan Conference has been 2016—2017 Cut Knife PP October 1 listed once in this one year prayer cycle. Davidson-Girvin RB Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Sponsored by July 30 Imperial RB The Saskatchewan Conference Delisle—Vanscoy RB KeLRose GS Eatonia-Mantario PP Kindersley: St. Paul’s PP Faith Formation Network Earl Grey WA October 8 Edgeley GS Kinistino TA August 6 Kipling TV Dundurn, Hanley RB Saskatoon: Knox RB Regina: Eastside WA Regina: Knox Metropolitan WA Esterhazy: St. -

Gazette Part I, August 13, 2021

THIS ISSUE HAS NO PART III (REGULATIONS)/CE NUMÉRO NE 2687 CONTIENT PAS DE PARTIE III (RÈGLEMENTS)THE SASKATCHEWAN GAZETTE, 13 août 2021 The Saskatchewan Gazette PUBLISHED WEEKLY BY AUTHORITY OF THE QUEEN’S PRINTER/PUBLIÉE CHAQUE SEMAINE SOUS L’AUTORITÉ DE L’IMPRIMEUR DE LA REINE PART I/PARTIE I Volume 117 REGINA, FRIDAY, AUGUST 13, 2021/REGINA, vendredi 13 août 2021 No. 32/nº32 TABLE OF CONTENTS/TABLE DES MATIÈRES PART I/PARTIE I ACTS NOT YET IN FORCE/LOIS NON ENCORE EN VIGUEUR ............................................................................................... 2688 ACTS IN FORCE ON ASSENT/LOIS ENTRANT EN VIGUEUR SUR SANCTION (First Session, Twenty-Ninth Legislative Assembly/Première session, 29e Assemblée législative) ................................................ 2692 ACTS IN FORCE ON SPECIFIC DATES/LOIS EN VIGUEUR À DES DATES PRÉCISES ................................................... 2693 ACTS IN FORCE ON SPECIFIC EVENTS/ LOIS ENTRANT EN VIGUEUR À DES OCCURRENCES PARTICULIÈRES ...................................................................... 2693 ACTS IN FORCE BY ORDER OF THE LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR IN COUNCIL/ LOIS EN VIGUEUR PAR DÉCRET DU LIEUTENANT-GOUVERNEUR EN CONSEIL (2021) ........................................ 2693 ACTS PROCLAIMED/LOIS PROCLAMÉES (2021) ....................................................................................................................... 2694 ORDER IN COUNCIL/DÉCRET ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Bylaw No. 3 – 08

BYLAW NO. 3 – 08 A bylaw of The Urban Municipal Administrators’ Association of Saskatchewan to amend Bylaw No. 1-00 which provides authority for the operation of the Association under the authority of The Urban Municipal Administrators Act. The Association in open meeting at its Annual Convention enacts as follows: 1) Article V. Divisions Section 22 is amended to read as follows: Subsection (a) DIVISION ONE(1) Cities: Estevan, Moose Jaw, Regina and Weyburn Towns: Alameda, Arcola, Assiniboia, Balgonie, Bengough, Bienfait, Broadview, Carlyle, Carnduff, Coronach, Fleming, Francis, Grenfell, Indian Head, Kipling, Lampman, Midale, Milestone, Moosomin, Ogema, Oxbow, Pilot Butte, Qu’Appelle, Radville, Redvers, Rocanville, Rockglen, Rouleau, Sintaluta, Stoughton, Wapella, Wawota, White City, Whitewood, Willow Bunch, Wolseley, Yellow Grass. Villages: Alida, Antler, Avonlea, Belle Plaine, Briercrest, Carievale, Ceylon, Creelman, Drinkwater, Fairlight, Fillmore, Forget, Frobisher, Gainsborough, Gladmar, Glenavon, Glen Ewen, Goodwater, Grand Coulee, Halbrite, Heward, Kendal, Kennedy, Kenosee Lake, Kisbey, Lake Alma, Lang, McLean, McTaggart, Macoun, Manor, Maryfield, Minton, Montmarte, North Portal, Odessa, Osage, Pangman, Pense, Roch Percee, Sedley, South Lake, Storthoaks, Sun Valley, Torquay, Tribune, Vibank, Welwyn, Wilcox, Windthorst. DIVISION TWO(2) Cities: Swift Current Towns: Burstall, Cabri, Eastend, Gravelbourg, Gull Lake, Herbert, Kyle, Lafleche, Leader, Maple Creek, Morse, Mossbank, Ponteix, Shaunavon. Villages: Abbey, Aneroid, Bracken, -

January 2020 Issue [email protected] Covering the Corner Is a Service Provided by the Town of Redvers

Thanks to our advertisers, please take your FREE Copy Covering The Corner Redvers & Area Community Newsletter January 2020 Issue [email protected] Covering the Corner is a service provided by the Town of Redvers. It is our intent to provide the community of Redvers and surrounding area with a newsletter that keeps residents connected with the numerous events and activities going on within our fantastic community! The Redvers Winterfest committee held their Winterfest on Saturday, December 14th. They had so many activities planned for the day, there was no shortage of things to do for all ages. The day kicked off with a pancake breakfast, there was a craft and trade show, a rice krispie sculpture display, curling, Santa photos, bouncy castles, a town wide scavenger hunt, Christmas ornament crafts, an adult paint class, sleigh rides, movie matinee just to name a few of the activities throughout the day and finished off with a Santa Parade. Check out page 7 to see more Winterfest photos. Thank you to Christina Birch for submitting all photos for Winterfest! Pictured above is the horses and sleigh from Meander Creek Pumpkin Patch at Oak Lake, Manitoba. Photo/Christina Birch TEEING UP TO SUPPORT COMMUNITY RESCUE COMMITTEE, RED COAT MUTUAL AID Submitted The WBL Ladies Tournament hosted by the Drive for Lives Committee was a ladies’ day out to enjoy camaraderie of good friends and sharing laughs on a spectacular golf course while supporting a life-saving organization. On July 19th, White Bear Lake Golf Course once again was bombarded with fun-loving women at the annual Drive for Lives Ladies Golf Tournament. -

Mississippian Subcrop Map and Selected Oil-Production Data, Southeastern Saskatchewan E

Open File 2011-56 Mississippian Subcrop Map and Selected Oil-Production Data, Southeastern Saskatchewan E. Nickel and C. Yang Location Map 102 Y Y h ' Y YY' Y Y Theoretical Type Log 103 ' Y * YY h' 104 hY YY Y Y Y Y Y 12 Y hh' Y ' Y Composite Log YY h 7 Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y h Y Y KENNEDY 50 ' Y ' Y Y Y YY '7'Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y 7'''''' h' Y Y Y LOWER WATROUS Y Y ' ' Y7'' ''Y' '' ' Y Y '''''''Y '7 ' ' CANADA h' Y 7''h'''''Y'' '''h'Y h' hh'' ' Y Y (!'71''' ' Y Y '' ' ' ' U.S.A. Y h' h ' Y''Y7 Y ''Y ' ' '' '' '' ' '' Y Y Y BIG SNOWY GROUP Y Y Y h' Y 7'7 ' Y Y Y 7 ' ''7' '' ''7Y ''''' ' Y Y 12 Y Y ' hY Yh ''Y ' 'h'' Y ' Y ' ' ''77'' ''' ' h Y MILESTONE Y h' Y '''''' ' YY Y ' '7'''' '' Y Y Y Y Y ' '''' '7' Y YY'''Y '7'''' '''hh''' Y h' h Y Yh' ''' h7 Y Y Y 7'7''''''Y 7'''h''7'' ''' 'hY Y 11 Y Y h' Y Y h 7''''''''''7 7 Y Y' ''' Y''''''''''' ' ' Y 50 h' Y Y h h Y'Y Y '''''h'' ' ''7'Y ''' ' ' ' ' hh' ' Y Y Y OSAGE Y ' YY 'Y''''' Y '''''' 77Y7 Y ''YY' ' 'Y Y Y Y YYY Y Y 77' YY'''''' hY ''Y' Y '''' ' ''''h'''Y' Y ''7 Y ' Y h'' Y ' ''h 7 7 '''YY '''7' hh '''''Y '' 7hhYY'h7 YY7Y777''''Y ' YY 'Y' '' '''' Y Y Y Y Y 'Yh Y h' Y 7'' 7 Y 7 7 7Y' ' ''''Y''' Y (!'6' Y Y Y '' ''' ' ''' ''Y Y Y Y h 7'' Y Y Y''7 Y Y ''h''Y Y Y 7''7 Y ''''''''''' Y 'hh7Y 7' h''' ''''7 WAWOTA Y Y Y Y Y Y Y ''' Y ' ' 7 Y Y 7 Y Y 'Y7'' 77«h77 YYY Y ' hY YhY '' ''Y ''' ''7h'' Y YY Y Y 7'''Y'''Y ''' 'Y YY' Y '''' Y' ''(!'5 Y''' '' ' '''' Y ' ' Y Y Y Y Y Y '''7'''' 'h ' h ' 7 ' Yh Y Y Y Y '''7'''''''' 7Y'Y'' YY ''h'''7 h'Y Y Y ''7 Y' 'h' 'h' 7 'h' Y ' YhhY 'Y'' '''' ' Y Y (!7 7 h FAIRLIGHTY -

Hansard: June 09, 1998

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF SASKATCHEWAN 1787 June 9, 1998 The Assembly met at 1:30 p.m. immediate action to ensure the required level of service in radiology is maintained in North Central Health District, Prayers and the priorities of its board be adjusted accordingly. ROUTINE PROCEEDINGS As in duty bound, your petitioners will ever pray. PRESENTING PETITIONS The communities involved, Mr. Speaker, are Melfort, St. Mr. Krawetz: — Thank you, Mr. Speaker. Mr. Speaker, I have Benedict, Pleasantdale, Tisdale, many corners of the province. I a petition to present on behalf of many people in Saskatchewan. so present. The prayer reads as follows: Mr. Heppner: — Mr. Speaker, I too rise to present a petition, Wherefore your petitioners humbly pray that your Hon. and these are signed from people from Parkside, Shellbrook, Assembly may be pleased to cause the government to take Vonda, Edam, and basically from communities all over immediate action to ensure that the required level of Saskatchewan, and the intent of the petition is to request the service in radiology is maintained in the North Central cancellation of the severance payments to Jack Messer. I so Health District and the priorities of its board be adjusted present. accordingly. Mr. Gantefoer: — Thank you, Mr. Speaker. I too rise on And as in duty bound, your petitioners ever pray. behalf of citizens from all through the north-east — Melfort, Kinistino, Star City, Tisdale, Nipawin, Pleasantdale, and even Mr. Speaker, the signatures to this come from many Regina, Mr. Speaker — concerned about adequate funding for communities in north-central Saskatchewan, communities like radiology service in Melfort. -

Safe Restart -Municipal Allocations- 2020Sep3.Xlsx

Safe Restart Municipal Allocations General Transit Total Allocation 2016 Allocation Allocation ( Per Capita ( Per Rider $0.3486) Municipality Type Census $59.65) Estevan C 11,483 $ 685,007 $ ‐ $ 685,007 Humboldt C 5,869 $ 350,109 $ ‐ $ 350,109 Lloydminster C 11,765 $ 701,829 $ ‐ $ 701,829 Martensville C 9,645 $ 575,363 $ ‐ $ 575,363 Meadow Lake C 5,344 $ 318,791 $ ‐ $ 318,791 Melfort C 5,992 $ 357,447 $ ‐ $ 357,447 Melville C 4,562 $ 272,142 $ ‐ $ 272,142 Moose Jaw C 33,890 $ 2,021,674 $ 161,167 $ 2,182,841 North Battleford C 14,315 $ 853,947 $ ‐ $ 853,947 Prince Albert C 35,926 $ 2,143,130 $ 141,453 $ 2,284,582 Regina C 215,106 $ 12,831,933 $ 3,457,367 $ 16,289,300 Saskatoon C 247,201 $ 14,746,528 $ 4,306,014 $ 19,052,542 Swift Current C 16,604 $ 990,495 $ ‐ $ 990,495 Warman C 11,020 $ 657,387 $ ‐ $ 657,387 Weyburn C 10,870 $ 648,439 $ ‐ $ 648,439 Yorkton C 16,343 $ 974,925 $ ‐ $ 974,925 TOTAL CITIES 16 Aberdeen T 669 $ 39,909 $ ‐ $ 39,909 Alameda T 369 $ 22,012 $ ‐ $ 22,012 Allan T 644 $ 38,417 $ ‐ $ 38,417 Arborfield T 312 $ 18,612 $ ‐ $ 18,612 Arcola T 657 $ 39,193 $ ‐ $ 39,193 Asquith T 639 $ 38,119 $ ‐ $ 38,119 Assiniboia T 2,424 $ 144,601 $ ‐ $ 144,601 Balcarres T 587 $ 35,017 $ ‐ $ 35,017 Balgonie T 1,765 $ 105,289 $ ‐ $ 105,289 Battleford T 4,429 $ 264,208 $ ‐ $ 264,208 Bengough T 332 $ 19,805 $ ‐ $ 19,805 Bienfait T 762 $ 45,456 $ ‐ $ 45,456 Big River T 700 $ 41,758 $ ‐ $ 41,758 Biggar T 2,226 $ 132,790 $ ‐ $ 132,790 Birch Hills T 1,033 $ 61,623 $ ‐ $ 61,623 Blaine Lake T 499 $ 29,767 $ ‐ $ 29,767 Bredenbury T 372 $ 22,191 $ -

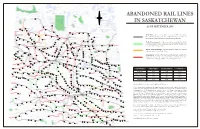

Abandoned Rail Lines in Saskatchewan

N ABANDONED RAIL LINES W E Meadow Lake IN SASKATCHEWAN S Big River Chitek Lake AS OF SEPTEMBER 2008 Frenchman Butte St. Walburg Leoville Paradise Hill Spruce Lake Debden Paddockwood Smeaton Choiceland Turtleford White Fox LLYODMINISTER Mervin Glaslyn Spiritwood Meath Park Canwood Nipawin In-Service: rail line that is still in service with a Class 1 or short- Shell Lake Medstead Marshall PRINCE ALBERT line railroad company, and for which no notice of intent to Edam Carrot River Lashburn discontinue has been entered on the railroad’s 3-year plan. Rabbit Lake Shellbrooke Maidstone Vawn Aylsham Lone Rock Parkside Gronlid Arborfield Paynton Ridgedale Meota Leask Zenon Park Macdowell Weldon To Be Discontinued: rail line currently in-service but for which Prince Birch Hills Neilburg Delmas Marcelin Hagen a notice of intent to discontinue has been entered in the railroad’s St. Louis Prairie River Erwood Star City NORTH BATTLEFORD Hoey Crooked River Hudson Bay current published 3-year plan. Krydor Blaine Lake Duck Lake Tisdale Domremy Crystal Springs MELFORT Cutknife Battleford Tway Bjorkdale Rockhaven Hafford Yellow Creek Speers Laird Sylvania Richard Pathlow Clemenceau Denholm Rosthern Recent Discontinuance: rail line which has been discontinued Rudell Wakaw St. Brieux Waldheim Porcupine Plain Maymont Pleasantdale Weekes within the past 3 years (2006 - 2008). Senlac St. Benedict Adanac Hepburn Hague Unity Radisson Cudworth Lac Vert Evesham Wilkie Middle Lake Macklin Neuanlage Archerwill Borden Naicam Cando Pilger Scott Lake Lenore Abandoned: rail line which has been discontinued / abandoned Primate Osler Reward Dalmeny Prud’homme Denzil Langham Spalding longer than 3 years ago. Note that in some cases the lines were Arelee Warman Vonda Bruno Rose Valley Salvador Usherville Landis Humbolt abandoned decades ago; rail beds may no longer be intact. -

Health Care Services Guide

423 Health Care Services Guide Sun Country Health Region TABLE OF CONTENTS SERVING THE MUNICIPALITIES AND SURROUNDING COMMUNITIES OF..... Health Region Office ................................424 Alameda Fife Lake Kisbey Pangman General Inquiries ......................................424 Ambulance ................................................424 Alida Fillmore Lake Alma Radville Bill Payments ...........................................424 Antler Forget Lampman Redvers Communications ......................................424 Arcola Frobisher Lang Roche Percee Employment Opportunities .....................424 Bengough Gainsborough Macoun Storthoaks Quality of Care Coordinator ....................424 Bienfait Gladmar Manor Stoughton Health Care Services Guide 24 Hour Help/Information Lines ..............424 Carievale Glen Ewen Maryfield Torquay Health Care Services ................................424 Carlyle Glenavon McTaggart Tribune Home Care .................................................425 Carnduff Goodwater Midale Wawota Health Care Facilities ...............................425 Ceylon Halbrite Minton Weyburn District Hospitals ......................................425 Coronach Heward North Portal Windthorst Community Hospitals ...............................425 Creelman Kennedy Ogema Yellow Grass Health Centres ..........................................425 Estevan Kenosee Lake Osage Long Term Care Facilities ........................426 Fairlight Kipling Oxbow HealthLine .................................................426 Telehealth -

2019 Prayer Cycle

August 25 October 27 Colleston, Steep Creek Gray The Faith Formation Network hopes Crossroads (Semans, Raymore) Grenfell that communities of faith and September 1 Saskatoon: Grosvenor Park individuals will use this prayer cycle Our Ministry Education Institutions Gull Lake: Knox as a way to connect with other Cut Knife November 3 communities of faith Crossroads United (Maryfield, Hudson Bay Larger Parish by including them in weekly Wawota) (Hudson Bay, Prairie River) thoughts and prayers. Crystal Springs Regina: Heritage Davidson-Girvin (Davidson) Indian Head: St. Andrew’s Take note of when your own community September 8 November 10 of faith is included and remember Regina Native Outreach Ministry (new) Humboldt (Brithdir, Humboldt) Delisle—Vanscoy Ituna: Lakeside on that day the many others Earl Grey Kennedy (Kennedy, Langbank) who are holding you in their prayers. Region 4 Eatonia-Mantario (Eatonia) November 17 September 15 Restorative Justice Week Every community of faith and World Week for Peace in Palestine and Imperial special ministry in Region 4 has been Prayer Cycle Israel / UN International Day of Peace Kamsack: Westminister listed once in this prayer cycle. 2019 Dundurn, Hanley Kerrobert Edgeley Kinistino Five Oaks (SM) (Naicam, Spalding) November 24 September 22 Trans Day of Remembrance Care facilities KeLRose Regina: Eastside Kindersley: St. Paul’s Elrose Kipling Gainsborough, Carievale Saskatoon: Knox September 29 December 1 Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women World AIDS Day Esterhazy: St. Andrew’s Kelliher: St. Paul Eston: