2020 Oral History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psychology Collection

A GUIDE TO THE: PSYCHOLOGY COLLECTION Scope of the Collection The Library’s psychology collection contains approximately 3000 volumes. These include theoretical works, material on the history of the subject, and biographies. The collection covers the main branches of psychology, including social, cognitive, comparative and child psychology. Also represented in the Library’s holdings are theories such as psychoanalysis, and interdisciplinary fields including the psychology of religion, war-related trauma (shellshock), and parapsychology. Most material is in English but German, French and Russian are also represented. Shelving Arrangements The majority of the collection is shelved at S. Psychology, although there is a separate shelfmark for comparative psychology, S. Psychology (Animal). Material within the two shelfmarks is arranged on the shelves in single alphabetical sequences, not subdivided by geographical area or topic. The S. Psychology and S. Psychology (Animal) shelfmarks are sub-divisions of the Library’s Science & Miscellaneous classification. The sequence begins on Level 5, running up to S. Psychology, Jung and continues on Level 6 from S. Psychology, K. Oversize books designated as ‘quarto’ (4to.) in the Library’s catalogues will be found in the section of the Science & Misc., 4to. sequence on Level 5, at the shelfmarks S. Psychology, 4to. and S. Psychology (Animal), 4to. Relevant material in related subjects may also be located at a number of additional shelfmarks, so it is always worth consulting the printed and computer subject indexes. Interdisciplinary works on the relationship between psychology and other disciplines are often located in the relevant areas, e.g. A. Art for books on the psychology of art, Literature for literary criticism, and Philology (Gen.) for material on the psychology of language. -

Varieties of Fame in Psychology Research-Article6624572016

PPSXXX10.1177/1745691616662457RoedigerVarieties of Fame in Psychology 662457research-article2016 Perspectives on Psychological Science 2016, Vol. 11(6) 882 –887 Varieties of Fame in Psychology © The Author(s) 2016 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1745691616662457 pps.sagepub.com Henry L. Roediger, III Washington University in St. Louis Abstract Fame in psychology, as in all arenas, is a local phenomenon. Psychologists (and probably academics in all fields) often first become well known for studying a subfield of an area (say, the study of attention in cognitive psychology, or even certain tasks used to study attention). Later, the researcher may become famous within cognitive psychology. In a few cases, researchers break out of a discipline to become famous across psychology and (more rarely still) even outside the confines of academe. The progression is slow and uneven. Fame is also temporally constricted. The most famous psychologists today will be forgotten in less than a century, just as the greats from the era of World War I are rarely read or remembered today. Freud and a few others represent exceptions to the rule, but generally fame is fleeting and each generation seems to dispense with the lessons learned by previous ones to claim their place in the sun. Keywords fame in psychology, scientific eminence, history of psychology, forgetting First, please take a quiz. Below is a list of eight names. done. (Hilgard’s, 1987, history text was better known Please look at each name and answer the following three than his scientific work that propelled him to eminence.) questions: (a) Do you recognize this name as belonging Perhaps some of you recognized another name or two to a famous psychologist? (b) If so, what area of study without much knowing why or what they did. -

The Hiring of James Mark Baldwin and James Gibson Hume at Toronto in 1889

History of Psychology Copyright 2004 by the Educational Publishing Foundation 2004, Vol. 7, No. 2, 130–153 1093-4510/04/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/1093-4510.7.2.130 THE HIRING OF JAMES MARK BALDWIN AND JAMES GIBSON HUME AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO IN 1889 Christopher D. Green York University In 1889, George Paxton Young, the University of Toronto’s philosophy professor, passed away suddenly while in the midst of a public debate over the merits of hiring Canadians in preference to American and British applicants for faculty positions. As a result, the process of replacing Young turned into a continuation of that argument, becoming quite vociferous and involving the popular press and the Ontario gov- ernment. This article examines the intellectual, political, and personal dynamics at work in the battle over Young’s replacement and its eventual resolution. The outcome would have an impact on both the Canadian intellectual scene and the development of experimental psychology in North America. In 1889 the University of Toronto was looking to hire a new professor of philosophy. The normally straightforward process of making a university appoint- ment, however, rapidly descended into an unseemly public battle involving not just university administrators, but also the highest levels of the Ontario govern- ment, the popular press, and the population of the city at large. The debate was not pitched solely, or even primarily, at the level of intellectual issues, but became intertwined with contentious popular questions of nationalism, religion, and the proper place of science in public education. The impact of the choice ultimately made would reverberate not only through the university and through Canada’s broader educational establishment for decades to come but, because it involved James Mark Baldwin—a man in the process of becoming one of the most prominent figures in the study of the mind—it also rippled through the nascent discipline of experimental psychology, just then gathering steam in the United States of America. -

The History of Emotions Past, Present, Future Historia De Las Emociones: Pasado, Presente Y Futuro a História Das Emoções: Passado, Presente E Futuro

Revista de Estudios Sociales 62 | Octubre 2017 Comunidades emocionales y cambio social The History of Emotions Past, Present, Future Historia de las emociones: pasado, presente y futuro A história das emoções: passado, presente e futuro Rob Boddice Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/revestudsoc/939 ISSN: 1900-5180 Publisher Universidad de los Andes Printed version Date of publication: 1 October 2017 Number of pages: 10-15 ISSN: 0123-885X Electronic reference Rob Boddice, “The History of Emotions”, Revista de Estudios Sociales [Online], 62 | Octubre 2017, Online since 01 October 2017, connection on 04 May 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ revestudsoc/939 Los contenidos de la Revista de Estudios Sociales están editados bajo la licencia Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. 10 The History of Emotions: Past, Present, Future* Rob Boddice** Received date: May 30, 2017 · Acceptance date: June 10, 2017 · Modification date: June 26, 2017 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.7440/res62.2017.02 Como citar: Boddice, Rob. 2017. “The History of Emotions: Past, Present, Future”. Revista de Estudios Sociales 62: 10-15. https:// dx.doi.org/10.7440/res62.2017.02 ABSTRACT | This article briefly appraises the state of the art in the history of emotions, lookingto its theoretical and methodological underpinnings and some of the notable scholarship in the contemporary field. The predominant focus, however, lies on the future direction of the history of emotions, based on a convergence of the humanities and neuros- ciences, and -

History of Psychology: a Sketch and an Interpretation James Mark Baldwin (1913)

History of Psychology: A Sketch and an Interpretation James Mark Baldwin (1913) Classics in the History of Psychology An internet resource developed by Christopher D. Green York University, Toronto, Ontario History of Psychology: A Sketch and an Interpretation James Mark Baldwin (1913) Originally published London: Watts. Posted December 1999 - March 2000 To EZEQUIEL, A. CHAVEZ PROFESSOR, DEPUTY, FORMERLY UNDER-SECRETARY OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION AND FINE ARTS IN MEXICO; A ZEALOUS PATRIOT, A PROFOUND SCHOLAR AND A LOYAL FRIEND PREFACE THE proposal to prepare the History of Psychology for this series appealed to me for other than the usual reasons. In the first place, singular as it may seem, :there is no history of psychology of any kind in book form in the English language.[l] Some years ago, I .projected as Editor a series of historical works to be written by various authorities on central psychological topics, the whole to constitute a "Library of Historical Psychology." These works, some twelve in number, are in course of preparation, and certain of them are soon to appear; but up to now no one of them has seen the light. The present little work of course in no way duplicates any of these. In French, too, there is no independent history. The German works, of which there are several,[2] had become hat old when last year two short histories appeared, written by Prof. Dessoir and Dr. Klemm. refer to these again just below. Another reason of a personal character for my entering this field is worth mentioning, since it explains scope and method of the present sketch. -

History of Psychology

The Psych 101 Series James C. Kaufman, PhD, Series Editor Department of Educational Psychology University of Connecticut David C. Devonis, PhD, received his doctorate in the history of psychology from the University of New Hampshire’s erstwhile pro- gram in that subject in 1989 with a thesis on the history of conscious pleasure in modern American psychology. Since then he has taught vir- tually every course in the psychology curriculum in his academic odys- sey from the University of Redlands in Redlands, California, and the now-closed Teikyo Marycrest University (formerly Marycrest College in Davenport, Iowa) to—for the past 17 years—Graceland University in Lamoni, Iowa, alma mater of Bruce Jenner and, more famously for the history of psychology, of Noble H. Kelly (1901–1997), eminent con- tributor to psychology’s infrastructure through his many years of ser- vice to the American Board of Examiners in Professional Psychology. Dr. Devonis has been a member of Cheiron: The International Society for the History of Behavioral and Social Sciences since 1990, a con- tributor to many of its activities, and its treasurer for the past 10 years. Currently he is on the editorial board of the American Psychological Association journal History of Psychology and is, with Wade Pickren, coeditor and compiler of the online bibliography History of Psychology in the Oxford Bibliographies Online series. History of Psychology 101 David C. Devonis, PhD Copyright © 2014 Springer Publishing Company, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or trans- mitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Springer Publishing Company, LLC, or authorization through payment of the appropriate fees to the Copyright Clearance Cen- ter, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600, [email protected] or on the Web at www.copyright.com. -

Download a History of Psychology a Global Perspective 2Nd Edition

A HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE 2ND EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Eric Shiraev | --- | --- | --- | 9781452276595 | --- | --- A History of Psychology: A Global Perspective / Edition 2 South African Journal of Psychology37 3 These four formed the core of the Chicago School of psychology. Focusing on Contemporary Issues Lesson 1. It was twelve years, however, before his two-volume The Principles of Psychology would be published. Augoustinos, M. Though other medical documents of ancient times were full of incantations and applications meant to turn away disease-causing demons and other superstition, the Edwin Smith Papyrus gives remedies to almost 50 conditions and only two contain incantations to ward off evil. Historians of psychology are beginning to focus on and value the indigenous point of view Brock, ; Pickren, It contains criticisms of then-current explanations of a number of problems of perception, and the alternatives offered by the Gestalt school. Gall's ultra-localizationist position with respect to the brain was soon attacked, most notably by French anatomist Pierre Flourens —who conducted ablation studies on chickens which purported to demonstrate little or no cerebral localization of function. Concepts of social A History of Psychology A Global Perspective 2nd edition in community psychology: Toward a social ecological epistemology. Lewis-Beck, A. Theory and Psychology16 4. Yet without direct supervision, he soon found a remedy to this boring work: exploring why children made the mistakes they did. Its Adjustments, Accuracy, and Control". For more than 50 years, professional psychologists in the United States have been governed by a model of training that specifies the doctorate as the entry-level degree into the profession. -

Psychology and Its History

2 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCING PSYCHOLOGY'S HISTORY • Distinguish between primary and secondary sources of historical information and describe the kinds of primary source information typically found by historians in archives • Explain how the process of doing history can produce some degree of confidence that truth has been attained PSYCHOLOGY AND ITS HISTORY One hundred is a nice round number and a one-hundredth anniversary is ample cause for celebration. In recent years, psychologists with a sense of history have celebrated often. The festivities began back in 1979, with the centennial of the founding of Wilhelm Wundt's laboratory at Leipzig, Germany. In 1992, the American Psychological Associ ation (APA) created a yearlong series of events to commemorate the centennial of its founding in G. Stanley Hall's study at Clark University on July 8, 1892. During the cen tennial year, historical articles appeared in all of the APA's journals and a special issue of American Psychologist focused on history; several books dealing with APA's history were commissioned (e.g., Evans, Sexton, & Cadwallader, 1992); regional conventions had historical themes; and the annual convention in Washington featured events ranging from the usual symposia and invited addresses on history to a fancy dress ball at Union Station featuring period (1892) costumes and a huge APA birthday cake. Interest in psychology's history has not been limited to centennial celebrations, of course. Histories of psychology were written soon after psychology itself appeared on the academic scene (e.g., Baldwin, 1913), and at least two of psychology's most famous books, E. G. -

10/2016 Robert H. Wozniak Education Ph.D. (Developmental Psychology

10/2016 Robert H. Wozniak Education Ph.D. (Developmental Psychology), University of Michigan. Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1971 A.B. (Psychology), College of the Holy Cross. Worcester, Massachusetts, 1966 Employment Department of Psychology, Bryn Mawr College. Katharine Elizabeth McBride Lecturer, 1980-81. Associate Professor, 1981-1986. Chair, Department of Human Development and Director, Child Study Institute, 1985-1993. Professor, 1986-Current Department of Psychology, University of Pittsburgh. Visiting Professor, Spring 2008, Fall 2008, Spring 2010, Fall 2015, Fall 2016 Psychology Department, Columbia University Teachers College. Visiting Assistant Professor, 1979-1980 Research, Development, and Demonstration Center in Education of Handicapped Children, University of Minnesota. Research Associate & Project Director, 1976-1978 Institute of Child Development, University of Minnesota. Assistant Professor, 1971-1976 P rofessional Societies Cheiron Society for the History of the Behavioral Sciences (Member, 1975- Current; Program Chair, 1990; Chair, Executive Committee, 1990-1993) Jean Piaget Society (Member, 1980-1995; Board of Directors, 1981-1985, 1987-1989; President, 1985-1987) Wozniak 2 Academic Honors Cattell Fellow, 1986-1987 Professional Consultantships/Editorial Board Memberships Life: The Excitement of Biology, Editorial Board. 2013-Current Center for the History of Psychology, University of Akron, Board of Directors, 2011-Current European Yearbook of the History of Psychology (formerly Teorie e Modelli), Editorial Board, 2000-Current Archives for the History of American Psychology. Instruments, Apparatus, and Exhibits Advisory Group, Member, 2002-2011 Dictionary of Modern American Philosophers, Supervising Editor for Psychology, 2001-2005. Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century British Philosophers, Psychology Editor, 2000-2002 New Ideas in Psychology, Editorial Board, 1983-1995 National Library of Medicine, Consultant, 1992-1993 Public Broadcasting System, Childhood series, Consultant, 1989-1991 Series Editorships Foundations of the History of Psychology. -

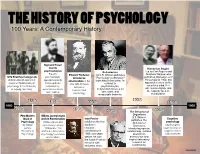

02B Psych Timeline.Pages

THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY 100 Years: A Contemporary History Sigmund Freud founds Humanism Begins psychoanalysis Behaviorism Led by Carl Rogers and Freud's Edward Titchener John B. Watson publishes Abraham Maslow, who 1879 First Psychology Lab psychoanalytic introduces "Psychology as Behavior," publishes Motivation and Personality in 1954, this Wilhelm Wundt opens first approach asserts structuralism in the launching behaviorism. In experimental laboratory in that people are contrast to approach centers on the U.S. with his book conscious mind, free psychology at the University motivated by, Manual of psychoanalysis, of Leipzig, Germany. unconscious drives behaviorism focuses on will, human dignity, and Experimental the capacity for self- and conflicts. observable and Psychology measurable behavior. actualization. 1938 1890 1896 1906 1956 1860 1960 1879 1901 1913 The Behavior of 1954 Organisms First Modern William James begins B.F. Skinner Ivan Pavlov Cognitive Book of work in Functionalism publishes The Psychology William James and publishes the first Behavior of psychology By William John Dewey, whose studies in Organisms, psychologists James, 1896 article "The classical introducing operant begin to focus on Principles of Reflex Arc Concept in conditioning in conditioning. It draws cognitive states Psychology Psychology" promotes 1906; two years attention to and processes functionalism. before, he won behaviorism and the Nobel Prize for inspires laboratory his work with research on salivating dogs. conditioning. Name _________________________________Date _________________Period __________ THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY A Contemporary History Use the timeline from the back to answer the questions. 1. What happened earlier? A) B.F. Skinner publishes The Behavior of Organism B) John B. Watson publishes Psychology as Behavior 2. -

The Story of Psychology the Story of Psychology

PROLOGUE The Story of Psychology The Story of Psychology Preview Psychology traces its roots back to Greek philosophers’ reflections on human nature. Psycholo gists’ initial focus on mental life was replaced in the 1920s by the study of observable behavior. As the science of behavior and mental processes, psychology had its origins in many disciplines and many countries. Psychology’s most enduring issue concerns the relative contributions of biology and experi- ence. Today, psychologists recognize that nurture works on what nature endows. The biopsycho- social approach incorporates biological, psychological, and social-cultural levels of analysis. Al though different perspectives on human nature have their own purposes and questions, they are complementary and together provide a fuller understanding of mind and behavior. Some psychologists conduct basic or applied research; others provide professional services, including assessing and treating troubled people. With its perspectives ranging from the biologi- cal to the social, and settings from the clinic to the laboratory, psychology has become a meeting place for many disciplines. Mastering psychology requires active study. A survey-question-read-retrieve-review study method boosts students’ learning and performance. Guide Introductory Exercise: Fact or Falsehood? The Preface to these Lecture Guides includes a Fact or Falsehood questionnaire that covers the entire text, with one item from each chapter. If you have not already used it, you may want to do so now as part of your introduction to the discipline and the text as a whole. Alternatively, you may use Handout P–1 on the next page, the Fact or Falsehood exercise that relates only to the material in this Prologue. -

Routing the Roots and Growth of the Dramatic Instinct

Routing the Roots and Growth of the Dramatic Instinct Jeanne Klein Associate Professor Department of Theatre 1530 Naismith Dr., 317 Murphy University of Kansas Lawrence, KS 66045 (FAX) (785) 864-5251 (o) (785) 864-5576 (h) (785) 843-3744 [email protected] Unpublished paper. Abstract: The idea of a “dramatic instinct” is routed from its nineteenth-century roots in early childhood education and child study psychology through early twentieth-century theatre education. This historically contextualized routing suggests the functional purposes of pretense for human freedom, self-preservation, and survival. Theatre scholars may influence the discipline of cognitive psychology by employing these philosophical and epistemological theories to unpack the role of empathy in aesthetic experiences with today’s spectators. Jeanne Klein is an associate professor of theatre at the University of Kansas where she teaches theatre for young audiences, child drama, and children’s media psychology. Her articles have appeared in the Journal of Dramatic Theatre and Criticism, Youth Theatre Journal, Journal of Aesthetic Education, and TYA Today, among others. This paper is dedicated to the memory of Robert Findlay whose text, Century of Innovation, co- authored with Oscar Brockett, taught me to innovate by taking scholarly and artistic risks. Routing the Roots and Growth of the Dramatic Instinct The term “dramatic instinct” refers simply to the human drive to dramatize. Dramatic (or pretend) play appears spontaneously in early childhood with few cultural variations as a provocative mystery of the human mind. For what functional purposes does this instinct for drama possibly serve humankind? After decades of innumerable investigations, developmental psychologists have concluded that this instinct for pretense is innate, universal, and cross- cultural, regardless of parental modeling (Lillard 188).