The Paper Shredder: Trails of Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

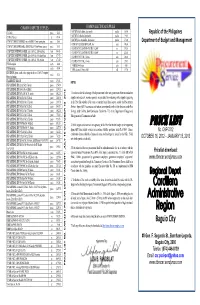

Plim Trading Inc Updated Pricelist As of 7-20-2020

Category Quantity UOM Item Code Item Description Wholesale Price Acetate BOX SFAX-A4 SUPERFAX ACETATE TRANSPARENCY FILM A4 (210MM X 297MM X 0.1MM) 230.00 Activity SET BINGO BINGO SET 80.00 Activity PC BL-ABA BOOKLET - ABAKADA 7.00 Activity PC BL-ALA BOOKLET - ALAMAT 7.00 Activity PC BL-BUG BOOKLET - BUGTONG 7.00 Activity PC BL-CP BOOKLET - COLORING PAD (ORDINARY) 7.00 Activity PC BL-PAB BOOKLET - PABULA 7.00 Activity PC BL-SB BOOKLET - STORY BOOK (ORDINARY) 7.00 Activity PC COL-STORY COLORED STORY BOOK 13.00 Activity SET 3462 DOMS MATHEMATICAL DRAWING INTRUMENT BOX 39.00 Activity PC PCLOCK PAPER CLOCK 6.00 Activity PC PTE1218 PERIODIC TABLE OF ELEMENTS 1218 (BIG) 9.00 Activity PC PTE912 PERIODIC TABLE OF ELEMENTS 9X12 (SMALL) 5.50 Activity SET P-MONEY PLAY MONEY 33.00 Activity PC POCKETBOOK POCKET BOOK - TAGALOG/ENGLISH 13.00 Activity PACK POP-C POPSICLE STICK - COLORED (50PCS/PACK) 10.00 Activity PACK POP-P POPSICLE STICK - PLAIN (50PCS/PACK) 9.00 Activity PC SB-ELFE SMART BOOK - EL FELIBUSTERISMO 33.00 Activity PC SB-FLOR SMART BOOK - FLORANTE AT LAURA 33.00 Activity PC SB-IA SMART BOOK - IBONG ADARNA 33.00 Activity PC SB-NOLI SMART BOOK - NOLI ME TANGERE 33.00 Activity PACK WC-A1 WINDOW CARD (50PCS/PACK) A1 100.00 Activity PACK WC-A2 WINDOW CARD (50PCS/PACK) A2 100.00 Activity PACK WC-A3 WINDOW CARD (50PCS/PACK) A3 100.00 Activity PACK WC-A4 WINDOW CARD (50PCS/PACK) A4 100.00 Activity PACK WC-D1 WINDOW CARD (50PCS/PACK) D1 100.00 Activity PACK WC-D2 WINDOW CARD (50PCS/PACK) D2 100.00 Activity PACK WC-D3 WINDOW CARD (50PCS/PACK) D3 -

Amazonbasics 12-Sheet Cross Cut Paper with CD and Credit Card Shredder Instruction Manual

PATENTED AmazonBasics 12-Sheet Cross Cut Paper with CD and Credit Card Shredder Instruction Manual B07FYH1DS8 Instruction Manual · English AmazonBasics 12-Sheet Cross Cut Paper with CD and Credit Card Shredder CONTENTS Make sure that the package contains the following: Shredder Quick Guide Instruction Manual ENGLISH 3 Warning: Read Safety Instructions Before Using! Read all instructions carefully Do not spray or keep any before installing or using the aerosol products in or around shredder. the shredder. Avoid touching the feed slot with Keep loose clothing or jewelry hands. away from the feed slot. Product is not intended for use Avoid getting hair near the feed by children (product is not a toy). slot. Do not insert foreign objects into the feed slot. • Always turn the shredder off and unplug the power cord from the AC outlet when not in use, before cleaning, moving, or emptying the waste basket. • RISK OF FIRE. Never use any petroleum based or flammable oils or lubricants in or around the machine as some oils can combust causing serious injury. • NEVER dispose of flammable chemicals OR materials that have come into contact with flammable chemicals (for example, nail polish, acetone and gasoline) in the shredder basket. • Never shred large paper clips, window or insulated envelopes, continuous forms, newsprint, bound pages (for example: notepads, checkbooks, magazines, etc...), transparencies, laminated documents, cardboard, any items with adhe- sives, hard materials or plastic (except Credit Cards and CDs). • Do not hold CD/DVD with finger through the center ring while feeding into the shredder. Serious injury may occur. • A socket-outlet should be near the equipment and be easily accessible. -

Working with the Media Introduction

Working with the Media Introduction Most municipal recycling coordinators wear lots of hats and juggle a number of jobs. It’s hard to focus on publicizing your community’s recycling program when you’re busy with the “real work” of overseeing operations, managing solid waste contractors and dealing with the public. That’s why MassDEP has created “Working with the Media” , a guide to getting free publicity for municipal waste reduction programs. This module is divided into 2 sections: Media Essentials and a Month-by-Month Outreach Planner . Media Essentials contains information on writing effective press releases and using public service announcements (PSA). It also includes two print PSAs that may be customized and submitted to your local newspaper. The Month-by-Month Outreach Planner covers a different topic each month and includes a press release(s), companion news article(s) and public service announcement(s). Select the topic you’d like to focus on, be it bottle and can recycling, yard waste, or holiday waste reduction. Customize the materials as you please, or send them “as is” it to local newspapers, radio and cable television stations to get the word out. We hope that these resources will help you to promote greater awareness of the benefits of recycling and waste reduction in your community. Working with the Media Working with the Media Table of Contents Below is a list of the items contained within this module. Items followed by a checkmark ( ) are provided in a modifiable electronic format. You are encouraged to customize these items to best meet the needs of your community. -

Paper Shredder Catalogue Systems

2012 LEPPERT BUSINESS PAPER SHREDDER CATALOGUE SYSTEMS INC Document Destruction For Privacy and Security | ENERGY SMART 1SS7 ES Shredder Throat width: 9.2” in. $255 Shred size: strip cut 1/4in - security level 2 Sheet capacity: 26 max Shred Speed: 5 feet/Min Can Shred: Paper, Paper Clips, CD’s, Staples, Credit Cards MADE IN Bin Capacity: 10.2 gal. “ENERGY SMART” ITALY -management system for power saving standby mode 24 hour’s continuous duty motor Automatic Start/Stop through electronic eyes Mounted on casters Shred OLD SECURITY PASSES Pull out bin for easy And CD ROMS emptying of collecting bag Please contact: JoAnna Wallace- Leppert Business Systems 905-333-8766 x 523 [email protected] www.leppert.com ENERGY SMART 2SS7 ES Shredder 2 Throats width: 9.2” in. - separates paper from plastic $396 Shred size: strip cut 1/4in - security level 2 Sheet capacity: 26 max Shred Speed: 5 feet/Min Can Shred: Paper, Paper Clips, CD’s, Staples, Credit Cards Bin Capacity: 10.2 gal. Warranty: Limited 1 yr on shredder, 5 years on cut blades “ENERGY SMART” MADE IN -management system for power saving standby mode ITALY 24 hour’s continuous duty motor Automatic Start/Stop through electronic eyes Mounted on casters CAN Shred: OLD SECURITY PASSES Pull out bin for easy And CD ROMS and Credit Cards emptying of collecting bag Please contact: JoAnna Wallace- Leppert Business Systems 905-333-8766 x 523 [email protected] www.leppert.com ENERGY SMART 260 CC4 Shredders Throat width: 10.25 in. Shred size: 1/8 x 1 1/8 in. -

ENVIRONMENT BUREAU CIRCULAR MEMORANDUM No. 6/2015 From: Permanent Secretary for the Environment/Director of Environmental Protec

ENVIRONMENT BUREAU CIRCULAR MEMORANDUM No. 6/2015 From: Permanent Secretary for the To: Permanent Secretaries, Environment/Director of Heads of Departments Environmental Protection Ref.: EP124/R3/103 Tel. No.: 3509 8602 Fax No.: 2838 2155 Date: 17 July 2015 Green Procurement in the Government Introduction The Chief Executive announced on 22 June 2009 that the Government would take the lead in making Hong Kong a green city through a number of measures including the expansion of green procurement in the Government. In this connection, the Permanent Secretary for the Environment has set up an Inter-departmental Working Group on Green Government Procurement (the Working Group), with membership and terms of reference as set out in Annex I, to take the matter forward. This Circular sets out the additional measures to expand green procurement in the Government, as endorsed by the Working Group. It supersedes the Environment Bureau Circular Memorandum No. 2/2011 issued on 11 March 2011. Government’s Green Procurement Policy 2. In 2000, the Government updated its procurement regulations to require bureaux and departments (B/Ds) to take into account environmental considerations when procuring goods and services. Specifically, B/Ds are encouraged, as far as possible and where economically rational, to purchase green products1 and avoid single-use 1 These refer to products (i) with improved recyclability, high recycled content, reduced packaging and greater durability; (ii) with greater energy efficiency; (iii) utilizing clean technology and/or clean fuels; 1 disposable items. In parallel, we continue to monitor the market situation and has expanded the list of green specifications for items commonly used by B/Ds. -

200 General Supplies PDF 1

200 General Supplies PDF Manufacturer Supplier Part Item # Name Description Manufacturer Supplier Price UOM Catalog Image Number Number Penmanship Paper - 8 1/2" X 11" With Red 500 sheets per ream. 10 reams per case. White, 15 lb. bond, 200100 Margin - 3/8" Spacing ruled on both sides, with a red margin line. PACON 2401 PAC2401 Brown & Saenger $30.50 CT Penmanship Paper - 8" X 10 1/2" With 11/32" 500 sheets per ream. 10 reams per case. White, 16 lb. bond, 200105 Spacing - No Margin ruled on both sides, no margin. PACON 2433 PAC2433 Brown & Saenger $27.80 CT 100 sheets per book. Sewn & bound for extra strength. Inside cover features a class schedule grid and other useful information. White sheets, 9 3/4" x 7 1/2", blue wide ruling with 200115 Composition Books red margin. MEAD 9910 MEA09910 Brown & Saenger $11.16 DOZ Ruled Paper - Grade 1 500 sheets per ream. Ruled the long way with red baseline. 8" x School Specialty 200120 - 5/8" Rule 10 1/2". 5/16" broken mid-line, 5/16" skip space. ZANER-BLOSER ZP2611 1387809 Inc $2.39 RM Penmanship Paper - 8 1/2" X 11" - No 500 sheets per ream. 10 reams per case. White, 15 lb. bond, 200150 Margin - 3/8" Spacing ruled on both sides, no margin. PACON 2403 PAC2403 Brown & Saenger $30.50 CT 500 sheets per ream. Ruled Long Way. 8" x 10 1/2" White Ruled Paper - Grade 2 newsprint, ruled with red baseline, light blue broken mid-line, School Specialty 200153 - 1/2" Rule and heavy blue headline. -

2018-Abilityone-Catalog Lz.Pdf

DISTRIBUTION LIST Job Name USSIV00086391 2018 AbilityOne Catalog ◊ Production File Name USSIV00086391_2018 AbilityOne Catalog_F0001_C0001 P2A Proof Date October 26, 2017 4:18 PM PAGE CONTROL EVENT CODE Page Info BLEED +0p9 TRIM 7.9375 × 10.375 A-1 0001 00.00 IF SUBCATEGORY_2<>‘DEFAULT’ SubCategory_1 | ENDIF CATEGORY THANK YOU FOR SUPPORTING TABLE OF CONTENTS X AMERICANS WHO ARE BLIND OR Badges A-02 SEVERELY DISABLED. Binders A-03 When you buy o ce supplies under the AbilityOne® program (formerly Boards A-03–A-06 the Javits-Wagner-O’Day (JWOD) program), you receive quality products Breakroom A-07 at competitive prices and you support the continued employment of people Calculators A-08 who are blind or who have other severe disabilities. Calendars A-08–A-09 Chair Mats A-09 About AbilityOne® Products Cleaning & Sanitation A-10–A-15 e AbilityOne® program generates employment and training for people Clipboards/Clips A-15–A-16 who are blind or have other severe disabilities through government Clocks A-17 purchases of supplies and services. ese products are manufactured by Computer Accessories A-18–A-20 organizations that belong to the National Industries for the Blind (NIB) Correction Supplies A-20 and Source America (serving people with severe disabilities). Desk Accessories A-21 Who must buy AbilityOne® Products? Envelopes A-22 AbilityOne® requirements apply to all federal entities—military and File Folders/Fasteners/Files A-22–A-26 civilian. e items shown on the next 56 pages ful ll your mandatory First Aid/Flags/Flashlights/Footrests A-27 source requirements under 41 CFR, Chapter 51 and FAR Subpart 8.7. -

BE IT HEREBY ORDAINED, by the Common Council of the City of Salem, County of County Solid Waste Management Plan to Be Source

CITY OF SALEM ORDINANCE NO. 0923 AN ORDINANCE AMENDING ARTICLE I OF CHAPTER 185 OF THE CITY OF SALEM CODE ENTITLED " RECYCLING" IN ORDER TO COMPLY WITH RECENT AMENDMENTS TO THE COUNTY OF SALEM SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PLAN BE IT HEREBY ORDAINED, by the Common Council of the City of Salem, County of Salem and State of New Jersey that Article I of Chapter 185 of the City Code entitled " Recycling" is hereby amended to read as follows: ARTICLE I RECYCLING 185- 1 — Short Title. This article shall be known and may be cited as the " City of Salem Recycling Program Ordinance". 185- 2 — Definitions. For the purpose of this subchapter, the following definitions shall apply unless the context clearly indicates or requires a different meaning: Commingled —means a combining of non-putrescible source -separated recyclable materials for the purpose of recycling; Designated Recyclable Materials — means those materials designated within the Salem County Solid Waste Management Plan to be source separated for the purpose of recycling by residential, commercial, institutional and industrial sectors. These materials cannot be deposited in the landfill and include: Residential Glass Containers ( 05): All glass containers used for packaging food or beverages Aluminum Cans ( 06): Food and beverage containers made entirely of aluminum Newspaper (03): All paper marketed as newsprint or newspaper and containing at least seventy percent ( 70%) newsprint or newspaper ( American Paper Institute grades # 6, # 7 and # 8 news). 112p11 N Mixed Office (02): All computer paper, all high-grade white paper ( including letterhead, typing paper, copier paper, onionskin, tissue, and notepad). Corrugated ( 01): Containers and similar paper items, usually used to transport supplies, equipment, parts, or other merchandise. -

Price List Whether of the Same Or Another Brand from Sources Outside the Procurement INK CARTRIDGE, HP C6656A, No

COMMON COMPUTER SUPPLIES COMMON ELECTRICAL SUPPLIES CD CASE piece 92.85 BATTERY, AAA, alkaline, 2pcs/packet packet 16.00 Republic of the Philippines CD Drive Cleaner pc 65.80 BATTERY, D, alkaline, 2pcs/packet packet 78.85 COMPACT DISK RECORDABLE, min. of 650MB, 70 min. running time piece 10.65 BATTERY, size AA, alkaline, 2pcs/packet packet 27.20 Department of Budget and Management COMPACT FLUORESCENT LAMP, 18w each 106.30 COMPACT DISK REWRITEABLE, HIGH SPEED, 700mb/80mins capacity piece 18.65 FLOURESCENT LIGHTING FIXTURE, 1 X 20W set 335.50 COMPUTER CONTINUOUS FORMS, 1 ply, 11x9-1/2", 2000 sets/box box 448.45 FLOURESCENT LIGHTING FIXTURE, 1 X 40W set 426.00 COMPUTER CONTINUOUS FORMS, 2 ply,11"x9-1/2, 1000 sheets/box box 574.70 FLOURESCENT TUBE, 18 watts each 26.00 COMPUTER CONTINUOUS FORMS, 3 ply, 11x9-1/2", 500 sets/box box 473.40 FLOURESCENT TUBE, 36 watts each 35.45 DVD Recordable each 14.40 STARTER, 4-40 watts each 4.00 DVD Rewritable each 40.50 TAPE, electrical, 19mm x 16M roll 19.70 EDP BINDER, plastic, asstd. colors, spring rod, for size 11"x9-1/2" computer each 35.15 forms, top binding FLASH DRIVE, USB 8GB each 479.25 NOTES: INK CARTRIDGE, HP 1823A, No.23, Tricolor piece 1,554.90 INK CARTRIDGE, HP 51645A, No. 45, Black piece 1,270.55 INK CARTRIDGE, HP C6578A/D, No. 78, tricolor piece 1,412.20 1. In order to take full advantage of bulk procurement in line with government efforts to standardize INK CARTRIDGE, HP C6615A, No. -

Design and Development of an Electric Paper Shredding Machine

546 Nigerian Research Journal of Engineering and Environmental Sciences 2(2) 2017 pp. 546-562 Original Research Article DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT OF AN ELECTRIC PAPER SHREDDING MACHINE 1Ogbeide, O.O., 1Nwabudike, P.N. and 2Igbinomwanhia, N.O. 1Department of Production Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University of Benin, Benin City, Nigeria. 2Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University of Benin, Benin City, Nigeria. *[email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] ARTICLE INFORMATION ABSTRACT Article history : Many a time we draft letters, set examination questions or even Received 08 September, 2017 write minutes of crucial meetings before getting them typed and Revised 30 October, 2017 these hand written ones are usually thrown into the waste paper Accepted 31 October, 2017 basket. It is possible that wrong persons may have access to the Available online 29 December, 2017 waste papers, collect and use them in wrong or negative ways. There are incidents of examination paper leakages arising from such practice. The aim of the work is to design and produce an Keywords : electric paper shredder that will help to provide an effective Paper shredding means of destroying secret or sensitive information on paper Design after use. The burden to proffer solution to the issue of disposal Fabrication of important information that can compromise business and Performance evaluation organization secret available on paper necessitated this Machine research. In carrying out this work consultation was carried out on types, operation and construction of paper shredding machine. Performance test was carried out by cutting A4 sized papers several times using the paper shredding machine produced and the average time to shred paper was 3.6 seconds. -

Project Report Template

College of Engineering Department of Mechanical Engineering Fall 2020-2021 Senior Design Project Report Paper Shredder Design In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering Team Members Student Name Student ID 1 Omran AlBahrani 201600939 2 Omar AlHajjaj 201702069 3 Abdulrahman AlQahtani 201403547 4 Mohammad AlDossary 201600975 Project Advisors: Advisor Name: Dr Fraj Alshmri Co-Advisor Name: Bouchaib Zazoum Abstract Nowadays, even though it is the era of technology and everything could be made in a soft- copy, hard-copies of A4 paper are still widely used and indispensable in every industry, every home, and every work office. However, hard-copy papers eventually need to be disposed in a proper way to not damage the environment and also to be reused again. The best way is to cut (shred) the paper in small pieces in order to recycle it easily. In this project, the goal of the team is to design a paper shredder with a DC motor, gears and two shafts with blades that are able to cross-cut paper in small, standard sizes (DIN P-4) for recycling purposes. Moreover, some papers are top-secret or classified papers (read & destroy) and shall not be leaked or read by people whom are not involved. Thus, shredding these papers in small sizes will be good for recycling purposes and will be excellent for securing classified papers and information and guarantees nothing will be leaked. Acknowledgments Foremost, it is the team’s honor to be under the supervision of our advisor Dr. Fraj AlShmri with his great experience in the field of Mechanical Engineering, the team members would like to thank him for his support in this project. -

Instruction Manual Amazonbasics 6-Sheet Cross-Cut Paper Shredder ASIN# B00HFJWKWK

Instruction Manual AmazonBasics 6-Sheet Cross-Cut Paper Shredder ASIN# B00HFJWKWK Customer Service 1-866-216-1072 WARNING: SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS, READ BEFORE USING! Read instructions before use. Do not spray or keep any aerosol products in or around the shredder. Avoid touching the document Keep loose clothing or jewelry feed opening with hands. away from the paper entry slot. Product is not intended for use by Avoid getting hair near the children (product is not a toy). paper entry slot. Do not insert foreign objects into the paper entry slot. • Always turn the shredder off and unplug the power cord from the AC outlet when not in use, before cleaning, moving, or emptying the waste basket. • RISK OF FIRE. Never use any petroleum based or flammable oils or lubricants in or around the machine as some oils can combust causing serious injury. • NEVER dispose of flammable chemicals or materials that have come into contact with flammable chemicals (for example, nail polish, acetone and gasoline) in the shredder basket. • Never shred large paper clips, window or insulated envelopes, continuous forms, newsprint, bound pages (for example: notepads, checkbooks, magazines, etc...), transparencies, laminated documents, cardboard, any items with adhesives, hard materials or plastic (except Credit Cards). • A socket-outlet should be near the equipment and be easily accessible. • Never let the wastebasket become full. This will lead to shredded material being pulled back up into the shredder and cause jams. • Never place the shredder near water or any heat source. • Do not use the shredder if the power cord is damaged in any way.