08 Appendix A-Bibliography Everett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

THEATRE DVD & Streaming & Performance

info / buy THEATRE DVD & Streaming & performance artfilmsdigital OVER 450 TITLES - Contemporary performance, acting and directing, Image: The Sydney Front devising, physical theatre workshops and documentaries, theatre makers and 20th century visionaries in theatre, puppets and a unique collection on asian theatre. ACTING / DIRECTING | ACTING / DEVISING | CONTEMPORARY PERFORMANCE WORKSHOPS | PHYSICAL / VISUAL THEATRE | VOICE & BODY | THEATRE MAKERS PUPPETRY | PRODUCTIONS | K-12 | ASIAN THEATRE COLLECTION STAGECRAFT / BACKSTAGE ACTING / DIRECTING Director and Actor: Passions, How To Use The Beyond Stanislavski - Shifting and Sliding Collaborative Directing in Process and Intimacy Stanislavski System Oyston directs Chekhov Contemporary Theatre 83’ | ALP-Direct |DVD & Streaming 68’ | PO-Stan | DVD & Streaming 110’ | PO-Chekhov |DVD & Streaming 54 mins | JK-Slid | DVD & Streaming 50’ | RMU-Working | DVD & Streaming An in depth exploration of the Peter Oyston reveals how he com- Using an abridged version of The works examine and challenge Working Forensically: complex and intimate relationship bines Stanislavski’s techniques in a Chekhov’s THE CHERRY ORCHARD, the social, temporal and gender between Actor and Director when systematic approach to provide a Oyston reveals how directors and constructs within which women A discussion between Richard working on a play-text. The core of full rehearsal process or a drama actors can apply the techniques of in particular live. They offer a Murphet (Director/Writer) and the process presented in the film course in microcosm. An invaluable Stanislavski and develop them to positive vision of the feminine Leisa Shelton (Director/Performer) involves working with physical and resource for anyone interested in suit contemporary theatre. psyche as creative, productive and about their years of collaboration (subsequent) emotional intensity the making of authentic theatre. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

04 Part Two Chapter 4-5 Everett

PART TWO. "So what are you doing now?" "Well the school of course." "You mean youre still there?" "Well of course. I will always be there as long as there are students." (Jacques Lecoq, in a letter to alumni, 1998). 79 CHAPTER FOUR INTRODUCTION TO PART TWO. The preceding chapters have been principally concerned with detailing the research matrix which has served as a means of mapping the influence of the Lecoq school on Australian theatre. I have attempted to situate the research process in a particular theoretical context, adopting Alun Munslow's concept of `deconstructionise history as a model. The terms `diaspora' and 'leavening' have been deployed as metaphorical frameworks for engaging with the operations of the word 'influence' as it relates specifically to the present study. An interpretive framework has been constructed using four key elements or features of the Lecoq pedagogy which have functioned as reference points in terms of data collection, analysis and interpretation. These are: creation of original performance material; use of improvisation; a movement-based approach to performance; use of a repertoire of performance styles. These elements or `mapping co-ordinates' have been used as focal points during the interviewing process and have served as reference points for analysis of the interview material and organisation of the narrative presentation. The remainder of the thesis constitutes the narrative interpretation of the primary and secondary source material. This chapter aims to provide a general overview of, and introduction to the research findings. I will firstly outline a demographic profile of Lecoq alumni in Australia. Secondly I will situate the work of alumni, and the influence of their work on Australian theatre within a broader socio-cultural, historical context. -

Ian Wooldridge Director

Ian Wooldridge Director For details of Ian's freelance productions, and his international work in training and education go to www.ianwooldridge.com Agents Nicki Stoddart [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0869 Credits Theatre Production Company Notes ARTISTIC DIRECTOR, ROYAL LYCEUM THEATRE COMPANY, EDINBURGH, 1984-1993 THE TAMING OF THE SHREW Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company, Edinburgh MERLIN Royal Lyceum Theatre Tankred Dorst Company Edinburgh ROMEO AND JULIET Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company Edinburgh THE CRUCIBLE Royal Lyceum Theatre Arthur Miller Company Edinburgh THE ODD COUPLE Royal Lyceum Theatre Neil Simon Company Edinburgh JUNO AND THE PAYCOCK Royal Lyceum Theatre Sean O'Casey Company Edinburgh OTHELLO Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company Edinburgh United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes THE HOUSE OF BERNARDA ALBA Royal Lyceum Theatre Federico Garcia Lorca Company Edinburgh HOBSON'S CHOICE Royal Lyceum Theatre Harold Brighouse Company Edinburgh DEATH OF A SALESMAN Royal Lyceum Theatre Arthur Miller Company Edinburgh THE GLASS MENAGERIE Royal Lyceum Theatre Tennessee Williams Company, Edinburgh ALICE IN WONDERLAND Royal Lyceum Theatre Adapted from the novel by Lewis Company, Edinburgh Carroll A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company Edinburgh A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE Royal Lyceum Theatre Tennessee Williams Company, Edinburgh THE NUTCRACKER SUITE Royal Lyceum -

Out of the (Play)Box: an Investigation Into Strategies for Writing and Devising

OUT OF THE (PLAY)BOX: AN INVESTIGATION INTO STRATEGIES FOR WRITING AND DEVISING By LAURA FRANCES HAYES A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of Master of Arts by Research Department of Drama and Theatre Arts College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham October 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Sarah Sigal observes that the ‘theatre-maker/writer/deviser Chris Goode has referred to […] a ‘phoney war’ between writing and devising’.1 This dissertation proposes a new method of playwriting, a (play)box, which in its ontology rejects any supposed binary division between writing and devising or text and performance. A (play)box is written not only in words, but also in a curated dramaturgy of stimuli – objects, music, video, images and experiences. Drawing on Lecoq’s pedagogy and in its etymology, a (play)box makes an invitation to playfully investigate its stimuli. It offers an embodied, sensory route into creation that initiates playful, affective relationships between the performers and provocations, harnessing the sensory capacities of the body in authorship. -

Company B ANNUAL REPORT 2008

company b ANNUAL REPORT 2008 A contents Company B SToRy ............................................ 2 Key peRFoRmanCe inDiCaToRS ...................... 30 CoRe ValueS, pRinCipleS & miSSion ............... 3 FinanCial Report ......................................... 32 ChaiR’S Report ............................................... 4 DiReCToRS’ Report ................................... 32 ArtistiC DiReCToR’S Report ........................... 6 DiReCToRS’ DeClaRaTion ........................... 34 GeneRal manaGeR’S Report .......................... 8 inCome STaTemenT .................................... 35 Company B STaFF ........................................... 10 BalanCe SheeT .......................................... 36 SeaSon 2008 .................................................. 11 CaSh Flow STaTemenT .............................. 37 TouRinG ........................................................ 20 STaTemenT oF ChanGeS in equiTy ............ 37 B ShaRp ......................................................... 22 noTeS To The FinanCial STaTements ....... 38 eDuCaTion ..................................................... 24 inDepenDenT auDiT DeClaRaTion CReaTiVe & aRTiSTiC DeVelopmenT ............... 26 & Report ...................................................... 49 CommuniTy AcceSS & awards ...................... 27 DonoRS, partneRS & GoVeRnmenT SupporteRS ............................ 28 1 the company b story Company B sprang into being out of the unique action taken to save Landmark productions like Cloudstreet, The Judas -

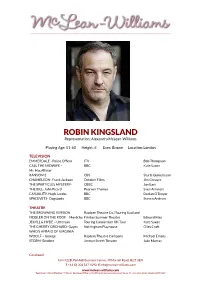

Mwm Cv Robinkingsland 2

ROBIN KINGSLAND Representation: Alexandra McLean-Williams Playing Age: 51-60 Height: 6’ Eyes: Brown Location: London TELEVISION EMMERDALE - Police Officer ITV Bob Thompson CALL THE MIDWIFE – BBC Kate Saxon Mr. MacAllister RANSOM 3 CBS Sturla Gunnarsson CHAMELEON- Frank Jackson October Films Jim Greayer THE SPARTICLES MYSTERY- CBBC Jon East THE BILL- John Picard Pearson Thames Sven Arnstein CASUALITY-Hugh Jacobs BBC Declan O’Dwyer SPACEVETS- Dogsbody BBC Steven Andrew THEATRE THE BROWNING VERSION Rapture Theatre Co,/Touring Scotland FIDDLER ON THE ROOF – Mordcha Frinton Summer Theatre Edward Max JEKYLL & HYDE – Utterson Touring Consortium UK Tour Kate Saxon THE CHERRY ORCHARD- Gayev Nottingham Playhouse Giles Croft WHO’S AFRAID OF VIRGINIA WOOLF – George Rapture Theatre Company Michael Emans STORM- Brother Jermyn Street Theatre Jake Murray Continued Unit F22B, Parkhall Business Centre, 40 Martell Road, SE21 8EN T +44 (0) 203 567 1090 E [email protected] www.mclean-williams.com Registered in England Number: 7432186 Registered Office: C/O William Sturgess & Co, Burwood House, 14 - 16 Caxton Street, London SW1H 0QY ROBIN KINGSLAND continued PRIVATE LIVES – Victor Mercury Theatre Colchester Esther Richardson ROMEO & JULIET – Montague Crucible Theatre Sheffield Jonathan Humphreys ARCADIA – Captain Bruce Nottingham Playhouse Giles Croft HAMLET- Claudius Secret Theatre, Edinburgh Fringe Richard Crawford Festival THE OTHER PLACE – Ian Smithson RADA Geoffrey Williams WITNESS FOR THE PROSECUTION Vienna English Theatre, Philip Dart Sir Wilfrid -

Crossing Boundaries Through La Commedia Dell'arte

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2007-08-15 Arlecchino's Journey: Crossing Boundaries Through La Commedia Dell'arte Janine Michelle Sobeck Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Sobeck, Janine Michelle, "Arlecchino's Journey: Crossing Boundaries Through La Commedia Dell'arte" (2007). Theses and Dissertations. 1200. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/1200 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ARLECCHINO’S JOURNEY: CROSSING BOUNDARIES THROUGH LA COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE By Janine Michelle Sobeck A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Theatre and Media Arts Brigham Young University December 2007 Copyright © 2007 Janine Michelle Sobeck Al Rights Reserved ii BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL Of a thesis submitted by Janine Michelle Sobeck This thesis has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. __________________________ ___________________________________ Date Megan Sanborn Jones, -

GS Teachers Pack2019

Teachers pack The Granny Smith Show An intimate, interactive performance piece mixing theatre, French, English and cooking! Summary The Show Questions and activities after the show The Character Set design Granny Smiths favourite activities French Various documents that can be used for an «easy» introduction to the french language Crumble à la poire – A little background information – The recipe (la recette) A few songs Masked Theatre Various documents with spoken, written and practical exercises – Mask use – Mask work – Bibliography The Granny Smith Show A comic, interactive, one woman show text and mask by Tracey Boot Role of Granny Smith Tracey Boot The Character The central character is called Granny Smith. Granny Smith is a retired, British, home economics teacher who has been living in France for a number of years. She speaks both French and English and sometimes both at the same time! She is a rather active granny who talks about her home, her likes and dislikes, her friends and activities… Question: What does Granny Smiths look like ? Activity: the students can either draw a picture or give a written account ie. french passeport / CV (name, address, physical appearance, hobbies… The Set Design: Granny Smiths house Our set is a simple but efficient interpretation of a small house: Stage right - a little living room (Petit salon) Stage left - the kitchen (cuisine) Question: What does Granny Smiths house look like ? Activity: the students can either draw a picture or give a written account Question: Who comes to Granny Smiths back door ? Answer: the post man (facteur) Granny Smiths favourite activities Granny Smith has lots of activities, she’s a very active granny! Here are some of her activities: 1) Gym (gymnastique) Granny Smith likes to keep fit she loves gym, jogging, football .. -

The Routledge Companion to Jacques Lecoq Mime, 'Mimes' And

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 02 Oct 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Routledge Companion to Jacques Lecoq Mark Evans, Rick Kemp Mime, ‘mimes’ and miming Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315745251.ch2 Vivian Appler Published online on: 18 Aug 2016 How to cite :- Vivian Appler. 18 Aug 2016, Mime, ‘mimes’ and miming from: The Routledge Companion to Jacques Lecoq Routledge Accessed on: 02 Oct 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315745251.ch2 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 2 MIME, ‘MIMES’ AND MIMING Vivian Appler At the height of the Nazi occupation of Paris, Marcel Carné (1906–96) raised a ghost. His 1945 film,Les Enfants du Paradis (Children of Paradise),1 reconstructs the mid-nineteenth cen- tury Boulevard du Temple (Boulevard of Crime) featuring the French pantomime popularized by Jean-Gaspard Deburau (1796–1846) at le Théâtre des Funambules (the Theatre of Tight- ropes). -

San a Ntonio

TEXAS San Antonio 115th Annual IAOM Conference and Expo Hyatt Regency Hotel and Henry B. Gonzalez Convention Center San Antonio, Texas USA International Association of Operative Millers 10100 West 87th Street, Suite 306 Overland Park, Kansas 66212 USA www.iaom.info Improve your solutions – trust Sefar Milling and Dry Food High-precision fabrics for screening and fi ltration in the production of cereal products Filtration Solutions Headquarters Sefar AG P.O Box Kansas City CH-9410 Heiden Sefar Filtration, Inc. Switzerland 4221 NE 34th Street fi [email protected] kcfi [email protected] president s message Welcome to the 115th annual conference and expo of the International Association of Opera- tive Millers, and to beautiful downtown San Antonio. For those of you new to Texas, welcome to the great Lone Star State! The 2011 conference offers IAOM’s traditional general sessions, product showcase, and technical presentations on facilities and employee man- agement, product protection and technical operations. The Program Com- mittee has done a tremendous job this year putting together the lineup of speakers. Even though the presentations are conducted simultaneously, you’ll be able to access the presentations online following the conference. Details about how to access the information will be sent by email to all IAOM members. While in San Antonio, we offer you the opportunity to network through shared meals, educational expeditions, informal meet- ings, receptions, and Expo. Conference highlights include: • Keynote Address on the Future of