Choosing a Hog Production System in the Upper Midwest Hogs Your Way

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children's Books

Children’s Books Packet for Festivus 2020 Olivia Murton 1. In this novel, several apartments are rented to people whose names are already printed on their mailboxes. A sign in an elevator in this novel announces that some toilet paper was found printed with the words BRAIDED KICKING TORTOISE SI A BRAT. That note refers to a girl in this novel who repeatedly kicks people in the shins, causing several other characters to develop temporary (*) limps and revealing that Barney Northrup and Sandy McSouthers are the same person. This novel was accurately described in HSQB Mafia 5 as containing “significant use of America the Beautiful lines as red herrings and clues.” For 10 points, name this Ellen Raskin mystery novel in which Turtle solves the clues left in the title millionaire’s will. ANSWER: The Westing Game 2. In one story in this series, a group of children encounters some Eastern Pipistrelles, and Tim announces that many of that book’s title animals live at his house. In the first book in this series, the narrator decides that the day is “not so boring after all” after visiting a water purification system, but is briefly stymied by a sand and gravel filter. The narrator in this series also says “now we knew how it felt to be a hamburger” shortly before making a classmate (*) sneeze. Dramatic events in this series cause one character’s earrings to glow and another character to announce “I knew I should have stayed home today.” The lizard Liz is a class pet who doubles as a driver in, for 10 points, what book and TV series about Ms. -

~Every Child Deserves to Be Well Fed and Well Led. the Office Will Be Closed Monday, May 31St, in Observance of Memorial Mark This Date Day

Look For Your Provider Number! Angela Castaneda found her number in our March/ April newsletter! There are 5 provider numbers hidden in this issue. If you find yours, call our office to claim your prize. Your name will appear in the next issue of the Child Care Outreach. WELCOME NEW PROVIDERS Family Service is celebrating 130 years 1891-2021 Victoria Almonte of Papillion, Keana Coffey of Omaha, Barbara Family Service Association of Lincoln is turning Faustman of Lincoln, Kaitlyn 130 years in 2021! Dating back to 1891, the way the agency has supported families has Gamble of Lincoln, Lucanica Gore evolved. Back then, the agency was called the of Omaha, Kirby Jensen of Scotia, Charity Organization Society. Our purpose was to Nakia Lockett of Omaha, Ashley coordinate relief funds as a third party between Lozier of Omaha, Debra Morrow of giver and receiver. Omaha, Kristie Oelrich of Pierce, A few years later, the Society’s constitution was Maria Ramirez of Omaha, Michelle changed to make direct relief giving an official Reyes of Grand Island, Lindsey function of the agency. Later, the Society’s Stumpf of Stapleton, Malisa efforts emphasized casework activity, and in 1917, the agencies name was changed to Social Subdon of Omaha, Mexy Swift of Welfare Society. Omaha, Kimberly Throener of Norfolk, Melanie Troutman- For more than 50 years the agency was located at Cushing of Omaha, Olivia Wilson 228 South 10th St. In 1945 the agency name was changed to Family Service Association of Lincoln of ONeill (our legal name today) and in 1959 purchased land to build a new office at 1133 H Street. -

Accelerated Reader Book List

Accelerated Reader Book List Book Title Author Reading Level Point Value ---------------------------------- -------------------- ------- ------ 12 Again Sue Corbett 4.9 8 13: Thirteen Stories...Agony and James Howe 5 9 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1 1906 San Francisco Earthquake Tim Cooke 6.1 1 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10 28 2010: Odyssey Two Arthur C. Clarke 7.8 13 3 NBs of Julian Drew James M. Deem 3.6 5 3001: The Final Odyssey Arthur C. Clarke 8.3 9 47 Walter Mosley 5.3 8 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4 The A.B.C. Murders Agatha Christie 6.1 9 Abandoned Puppy Emily Costello 4.1 3 Abarat Clive Barker 5.5 15 Abduction! Peg Kehret 4.7 6 The Abduction Mette Newth 6 8 Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3 The Abernathy Boys L.J. Hunt 5.3 6 Abhorsen Garth Nix 6.6 16 Abigail Adams: A Revolutionary W Jacqueline Ching 8.1 2 About Face June Rae Wood 4.6 9 Above the Veil Garth Nix 5.3 7 Abraham Lincoln: Friend of the P Clara Ingram Judso 7.3 7 N Abraham Lincoln: From Pioneer to E.B. Phillips 8 4 N Absolute Brightness James Lecesne 6.5 15 Absolutely Normal Chaos Sharon Creech 4.7 7 N The Absolutely True Diary of a P Sherman Alexie 4 6 N An Abundance of Katherines John Green 5.6 10 Acceleration Graham McNamee 4.4 7 An Acceptable Time Madeleine L'Engle 4.5 11 N Accidental Love Gary Soto 4.8 5 Ace Hits the Big Time Barbara Murphy 4.2 6 Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith 5.2 3 Achingly Alice Phyllis Reynolds N 4.9 4 The Acorn People Ron Jones 5.6 2 Acorna: The Unicorn Girl -

Olivia in India

Olivia in India O. Douglas The Project Gutenberg EBook of Olivia in India, by O. Douglas This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Olivia in India Author: O. Douglas Release Date: February 1, 2004 [EBook #10899] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK OLIVIA IN INDIA *** Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team. OLIVIA IN INDIA O. DOUGLAS "_When one discovers a happy look it is one's duty to tell one's friends about it_." JAMES DOUGLAS in _The Star_. OLIVIA IN INDIA. By O. DOUGLAS "Happy books are not very plentiful, and when one discovers a happy book it is one's duty to tell one's friends about it, so that it makes them happy too. My happy book is called 'Olivia.' It is by a certain young woman who calls herself O. Douglas, though I suspect that it's a pen-name.... Olivia can write the most fascinating letters you ever read."--JAMES DOUGLAS in the _Star_. "Extremely interesting. To have read this book is to have met an extremely likeable personality in the author."--_Glasgow Herald_. PENNY PLAIN. By O. DOUGLAS "Penny Plain" is a story of life in a little town on the banks of the Tweed. Jean Jardine, the heroine--who looks after her brothers in their queer old house, "The Rigs," and is in turn looked after by the old servant, Mrs. -

The Price We Pay for Corporate Hogs Table of Contents by Marlene Halverson I

IATP Hog Report http://www.iatp.org/hogreport/2/27/2006 3:49:57 AM Table of Contents The Price We Pay for Corporate Hogs Table of Contents By Marlene Halverson i. Executive Summary and Overview July 2000 I. Are Independent Farmers an Endangered Species? Sponsored by the Funding Group on Confined Animal Feeding Operations. II. Putting Lives in Peril Copyright 2000: Institute for Agriculture and Trade III. Building Sewerless Cities Policy IV. Part of the Pig Really Does Fly Dedicated to the V. The Hog Factory in the Backyard memory of Ruth Harrison VI. Pigs in the Poky Author of Animal Machines:The New VII. Stop the Madness Factory Farming Industry (1964). VIII. Funder to Funder June 1920-June 2000 IX. Animal Welfare Institute Husbandry Standards for Pigs Acknowledgements ● Contacts - Some organizations and individuals known to Home Page be working on the animal factory issue and humane, sustainable, and socially just alternatives. ● Funders Acknowledgements Sponsored by the Funding Group on Confined Animal Feeding Operations. Written by Marlene K. Halverson About the author: http://www.iatp.org/hogreport/indextoc.html (1 of 2)2/27/2006 3:49:58 AM Table of Contents Marlene Halverson was raised on a southern Minnesota dairy and crop farm. She is a Ph.D. candidate in agricultural economics at the University of Minnesota. In 1992, she was a guest researcher at the Department of Animal Health and Environment, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, where she studied the economic effects of animal protection legislation on Swedish hog farmers. She has visited farms and pig research institutes in several European countries. -

Eastern Progress 1978-1979 Eastern Progress

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Eastern Progress 1978-1979 Eastern Progress 1-11-1979 Eastern Progress - 11 Jan 1979 Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1978-79 Recommended Citation Eastern Kentucky University, "Eastern Progress - 11 Jan 1979" (1979). Eastern Progress 1978-1979. Paper 14. http://encompass.eku.edu/progress_1978-79/14 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Eastern Progress at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Eastern Progress 1978-1979 by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. wmm^mmm M Voluma 57, No. 15 Official Student Publication 14 January 11 1979 of Eattarn Kantucfcy Umviintv Winter ice storm blows snow removal plan into action By GINNY EAGER With the accumulation of one inch of Parking lots will be cleared next and Features Editor snow the removal begins Gabbard will as labor and equipment permits all use his judgment as to which equipment other college owned areas will be As of last weekend the University's will be used on different areas cleared. new Snow Removal Plan was enacted. Sweeping, sanding, plowing and the use Equipment available is a 1.5 ton If any areas become too dangerous for of Calcium Chloride will be used to truck, tractors with snow blades and safe travel and the snow cannot be remove the snow. blades to be affixed to University four- removed, the area will be posted, "With the fantastic amount of snow wheel drives. University farm equip- "Dangerous Walk Area. -

2016 Program Book

47th AASV Annual Meeting Plan now to thank February 27 - March 1, 2016 attend the you! New Orleans AASV 48TH We extend our sincere appreciation to Annual Meeting the following sponsors of AASV annual meeting activities: February 25 - 28, 2017 BOEHRINGER INGELHEIM VETMEDICA, INC Hyatt Regency Denver AASV Luncheon Standing on the DENVER, COLORADO CEVA ANIMAL HEALTH Refreshment Break Sponsor Shoulders of Giants: ELANCO ANIMAL HEALTH AASV Awards Reception Collaboration & Teamwork AASV Foundation Veterinary Student Scholarships HARRISVACCINES Refreshment Break Sponsor HOG SLAT Refreshment Break Co-sponsor MERCK ANIMAL HEALTH Student Reception Student Trivia Event NEWPORT LABORATORIES Veterinary Student Travel Stipends Veterinary Student Poster Awards 2018 San Diego March 3 - 6 STUART PRODUCTS 2019 Orlando March 9-12 Praise Breakfast AASV’s 50th Anniversary! ZOETIS Welcome Reception AASV Student Seminar and Student Poster Session AASV Foundation Veterinary Student Scholarship Message from the Program Hyatt Regency New Orleans Chair, Dr. George Charbonneau Level 2 Strand F A Our meeting in The Big Easy 10 10 11 11 12 12 13 13 is sure to provide some A B A B A B A B G E D B The Celestin warm weather that will be a H C welcome break from Old Man 9 8 7 6 14 Ballroom North Wing To Storyville Hall Winter. New Orleans offers 5 4 3 2 1 AASV Registration Strand Celestin Foyer Desk an exciting venue with its Foyer Cajun cuisine, New Orleans Restrooms Jazz and lots of history. As we Elevators Elevators gather in New Orleans we will 4 5 6 Escalators Escalators Freight have a wonderful opportunity Foster Bolden Elevator 1 8 Block Vitascope to renew relationships with 3 2 1 Kitchen & Hall friends and colleagues. -

Olivia Menu Temp.Xlsx

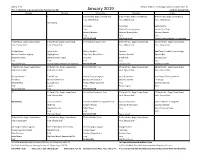

Olivia 7-12 Menu: Subject to change without notice due to This institution is an equal opportunity provider. January 2019 product availability. Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday 1 2 Benefit Bar, Bagel, Sweet Bread 3 Benefit Bar, Bagel, Sweet Bread 4 Benefit Bar, Bagel, Sweet Bread, Fruit, Cheese Stick Fruit, Cheese Stick Fruit, Cheese Stick NO SCHOOL Corn Dogs Pork Chop Beefy Nachos Fries Mashed Potato w/ gravy Yellow Corn Chips Steamed Broccoli Steamed Green Beans Steamed Carrots Fruit Fruit Fruit NO SALAD BAR Wg Sliced Bread Peanut Butter Sandwich on wg bread 7 Benefit Bar, Bagel, Sweet Bread, 8 Benefit Bar, Bagel, Sweet Bread, 9 Tornado (2), Yogurt, Fruit 10 Benefit Bar, Bagel, Sweet Bread, 11 Benefit Bar, Bagel, Sweet Bread, Fruit, Cheese Stick Fruit, Cheese Stick Fruit, Cheese Stick Fruit, Cheese Stick Chicken Strips Bosco Sticks BBQ on Wg Bun Lasagna Beef Taco/ Chicken Fajita w/fixings Mashed Potatoes w/gravy Dipping Sauce Curly Fries, Baked Beans Steamed Broccoli Spanish Rice Steamed Carrots Steamed Green Beans Cole Slaw Bread Stick Steamed Corn Fruit Fruit Fruit Fruit Fruit Wg Sliced Bread Peanut Butter Sandwich on wg bread NO SALAD BAR Caesar Salad Blueberry Muffin 14 Benefit Bar, Bagel, Sweet Bread, 15 Benefit Bar, Bagel, Sweet Bread, 16 Mini Waffles, Fruit 17 Benefit Bar, Bagel, Sweet Bread, 18 Benefit Bar, Bagel, Sweet Bread, Fruit, Cheese Stick Fruit, Cheese Stick Fruit, Cheese Stick Fruit, Cheese Stick Orange Chicken French Toast Chicken Patty on wg bun Soup & Sandwich Hot Cheesy Turkey Sandwich Fried Rice Cheesy Hashbrowns -

Cesspools of Shame: How Factory Farm Lagoons And

CESSPOOLS OF SHAME How Factory Farm Lagoons and Sprayfields Threaten Environmental and Public Health Author Robbin Marks Natural Resources Defense Council and the Clean Water Network July 2001 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Natural Resources Defense Council and the Clean Water Network wish to thank The McKnight Foundation, The Pew Charitable Trusts, Wallace Genetic Foundation, Inc., and The Davis Family Trust for Clean Water for their support of our work on animal feedlot issues. NRDC gratefully acknowledges the support of its 500,000 members, whose generosity helped make this report possible. We wish to thank the reviewers of this report, Nancy Stoner, Melanie Shepherdson Flynn, and Emily Cousins. We also thank a number of individuals for their help with this report, including: Rolf Christen, Kathy Cochran, Rick Dove, Scott Dye, Pat Gallagher, Nicolette Hahn, Marlene Halverson, Suzette Hafield, Susan Heathcote, Karen Hudson, Julie Jansen, Jack Martin, and Neil Julian Savage. ABOUT NRDC NRDC is a nonprofit environmental organization with more than 500,000 members. Since 1970, our lawyers, scientists, and other environmental specialists have been working to protect the worlds natural resources and improve the quality of the human environment. NRDC has offices in New York City, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, and San Francisco. ABOUT THE CLEAN WATER NETWORK The Clean Water Network is an alliance of over 1,000 organizations that endorse its platform paper, the National Agenda for Clean Water. The Agenda outlines the need for strong clean water safeguards in order to protect public health and the environment. The Clean Water Network includes a variety of organizations representing environmentalists, family farmers, commercial fishermen, recreational anglers, surfers, boaters, faith communities, environmental justice advocates, tribes, labor unions, and civic associations. -

AUDIENCE GUIDE Grades

Alliance Theatre for Youth and Families presents AUDIENCE GUIDE Grades 4-8 Based on the story by E.B. White Dramatized by Joseph Robinette Dramatic Publishing Directed by Rosemary Newcott Created by students and teachers participating in the Dramaturgy by Students Program Alliance Theatre Institute for Educators and Teaching Artists: Friends School of Atlanta, Sixth Grade Introduction This Audience/Study Guide has been prepared by Johnny Pride’s Sixth Grade Language Arts classes at the Friends School of Atlanta, in Decatur, GA. These students and their teacher participated in the Alliance Theatre Institute for Educators and Teaching Artists Dramaturgy by Students Program under the guidance of Teaching Artist Barry Stewart Mann. The intent of this guide is to provide background information as well as a starting point for further research and reading, both in preparation for and reflection on the Alliance Theatre for Youth and Families’ series production of Charlotte’s Web. The questions, information and activities have been created with the student audience in mind. Please feel free to use/copy any or all of the pages as you reflect with your students and families about the Charlotte’s Web at the Alliance Theatre. Bringing Charlotte’s Web into the classroom: Curriculum Connections This Audience Guide is targeted for students in grades 4-8 with activities which extend knowledge in the core subject of Language Arts and additional knowledge in Life Science, Social Studies, and Character Education. It also provides experiences in the strands of creative thinking, critical thinking, communication and research as well as all levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy. -

Animals As People in Children's Literature

JAN-LA2.QXD 12/2/2003 4:03 PM Page 205 Animals as People in Children’s Literature Books that use animals as people can add 205 Carolyn L. Burke Joby G. Copenhaver emotional distance for the reader when the Literature in Children’s Animals as People story message is powerful or painful. Ours is a highly literate culture, making use of written texts to orga- nize thought, to test beliefs, to convey what is valued, and to at- tempt to influence the actions and thoughts of others. It is not surpris- ing that for most of us, early child- hood memories include a favorite story. From among the many stories that we have heard or had read to us, there is often one that spoke more directly to us than the others, a story that touched an emotional chord, somehow reflecting a keenly felt need, concern, or set of values. This story stays fresh and whole in our minds. Hearing it revives old experiences and feelings we may have forgotten. We are able to recreate, in detail, who we were, what we were doing, the values and beliefs that we were developing, and how we were coming to relate to others and to our world. For Carolyn, that story is Little Red Hen (Galdone, 1985). The industri- ous mother and her chicks plant, weed, and finally harvest their wheat on their own when their animal friends continually make ex- cuses for their lack of help. However, when the wheat is ground and baked into bread, these same friends ea- gerly volunteer to eat it. -

COVID-19 and Local Meat Processing in the Midwest: Challenges and Emerging Business Practices

COVID-19 and Local Meat Processing in the Midwest: Challenges and Emerging Business Practices Authors: Dr. Kathryn Draeger, Christopher Danner, Natalie Barka, Eliza Theis, Joan Busch, Greg Schweser, Wayne Martin May 21, 2021 This project was supported by the University of Minnesota COVID Action Network, University of Minnesota Sustainable Development Goals, Extension Regional Sustainable Development Partnerships, and the Office of Undergraduate Research. The project team is grateful to the meat processors who made time to discuss their businesses with us. 2 Case Study Table of Contents Byron Center Meats - Mobile and Traditional Slaughter with USDA Processing 8 Clean Chickens & Co. - Mobile Poultry Processing 12 Dover Meats - Serving the Farm Community with USDA-inspected slaughter and processing 16 Gunthorp Farms - On-Farm Meat Processing 19 JM Watkins - “Main Street” Meat Processing 23 Prairie Meats - Meat Processing for Their Farm and Beyond 27 Rural Advantage - A Nonprofit Meat Processor 29 Y-Ker Acres - Specialty Processing with Outsourced Slaughter 32 Glossary 36 Work Cited 38 3 Introduction: Growing Demand for Local Foods Shows Need for Strong Meat Processing Sector Consumer interest in locally raised meats has steadily increased in recent decades, both nationally (Martinez, et al., 2010) and in the state of Minnesota (Renewing the Countryside, 2015). More farms are catering to this market by participating in farmers markets, selling through Community-Supported Agriculture (CSA), and conducting on-farm sales. In Minnesota, the number of farms registered through the state’s local foods directory has increased from 944 in 2012 (Minnesota Grown, 2012) to 981 in May 2021 (Minnesota Grown, 2020). Overall, 5 percent of Minnesota farms sell directly to consumers (National Agricultural Statistics Service, 2017), representing over 3,000 farms and $139 million in economic value according to analysis by the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) (2016, 2021).