Richard Winsten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

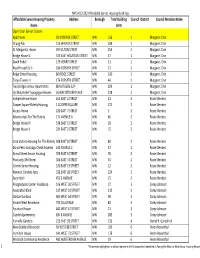

Master 202 Property Profile with Council Member District Final For

NYC HUD 202 Affordable Senior Housing Buildings Affordable Senior Housing Property Address Borough Total Building Council District Council Member Name Name Units Open Door Senior Citizens Apartment 50 NORFOLK STREET MN 156 1 Margaret Chin Chung Pak 125 WALKER STREET MN 104 1 Margaret Chin St. Margarets House 49 FULTON STREET MN 254 1 Margaret Chin Bridge House VI 323 EAST HOUSTON STREET MN 17 1 Margaret Chin David Podell 179 HENRY STREET MN 51 1 Margaret Chin Nysd Forsyth St Ii 184 FORSYTH STREET MN 21 1 Margaret Chin Ridge Street Housing 80 RIDGE STREET MN 100 1 Margaret Chin Tanya Towers II 174 FORSYTH STREET MN 40 1 Margaret Chin Two Bridges Senior Apartments 80 RUTGERS SLIP MN 109 1 Margaret Chin Ujc Bialystoker Synagogue Houses 16 BIALYSTOKER PLACE MN 128 1 Margaret Chin Independence House 165 EAST 2 STREET MN 21 2 Rosie Mendez Cooper Square Elderly Housing 1 COOPER SQUARE MN 151 2 Rosie Mendez Access House 220 EAST 7 STREET MN 5 2 Rosie Mendez Alliance Apts For The Elderly 174 AVENUE A MN 46 2 Rosie Mendez Bridge House IV 538 EAST 6 STREET MN 18 2 Rosie Mendez Bridge House V 234 EAST 2 STREET MN 15 2 Rosie Mendez Casa Victoria Housing For The Elderly 308 EAST 8 STREET MN 80 2 Rosie Mendez Dona Petra Santiago Check Address 143 AVENUE C MN 57 2 Rosie Mendez Grand Street Senior Housing 709 EAST 6 STREET MN 78 2 Rosie Mendez Positively 3Rd Street 306 EAST 3 STREET MN 53 2 Rosie Mendez Cabrini Senior Housing 220 EAST 19 STREET MN 12 2 Rosie Mendez Renwick Gardens Apts 332 EAST 28 STREET MN 224 2 Rosie Mendez Securitad I 451 3 AVENUE MN 15 2 Rosie Mendez Postgraduate Center Residence 516 WEST 50 STREET MN 22 3 Corey Johnson Associated Blind 137 WEST 23 STREET MN 210 3 Corey Johnson Clinton Gardens 404 WEST 54 STREET MN 99 3 Corey Johnson Encore West Residence 755 10 AVENUE MN 85 3 Corey Johnson Fountain House 441 WEST 47 STREET MN 21 3 Corey Johnson Capitol Apartments 834 8 AVENUE MN 285 3 Corey Johnson Yorkville Gardens 225 EAST 93 STREET MN 133 4 Daniel R. -

NYCDCC 2017 City Council Endorsements

New York City & Vicinity District Council of Carpenters Contact: Elizabeth McKenna Work Office: (212) 366-7326 Work Cell: (646) 462-1356 E-mail: [email protected] Monday, July 17, 2017 NYC Carpenters Endorse Candidates for City Council NEW YORK, NY - The New York City & Vicinity District Council of Carpenters, a representative body comprised of nine locals and nearly 25,000 members, endorsed candidates in several key City Council races today. The District Council supports these candidates because of their proven record of advocacy for union members and their families. “The Carpenters Union is proud to offer our endorsement and support to these candidates for City Council. They have demonstrated a firm commitment to our membership and all working class New Yorkers. We will work tirelessly to ensure their election and look forward to partnering with them in their role as Councilmembers.” -Joseph A. Geiger, Executive Secretary- Treasurer, NYC & Vicinity District Council of Carpenters The NYC District Council of Carpenters is known for their expansive field operation and is prepared to be an active force in the 2017 election cycle. The District Council views participation in the electoral process as critical to protecting the livelihood of its membership. Fighting for candidates that will represent working class men and women is a role the District Council proudly embraces. The full list of NYC District Council endorsed candidates can be found below: CD 2 (Lower East Side): Carlina Rivera CD 3 (Chelsea): Corey Johnson CD 5 (UES, -

PACE Endorsements

NASW NYC-PACE Endorsed Elected Officials PACE endorses candidates for political office who can best represent the interest of our clients and our profession. PACE then supports those endorsed candidates through financial contributions and/or by informing NASW members in those districts of our endorsements. The following is a list of PACE endorsed officials as of September 2013. New York City Public Advocate Letitia James New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer Bronx Borough President Ruben Diaz Jr. Queens Borough President Melinda Katz Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams New York City Council Margaret Chin District 1 Manhattan Rosie Mendez District 2 Manhattan Daniel Garodnick District 4 Manhattan Helen Rosenthal District 6 Manhattan Mark Levine District 7 Manhattan Melissa Mark-Viverito District 8 Manhattan Inez Dickens District 9 Manhattan Ydanis Rodriguez District 10 Manhattan Andrew Cohen District 11 Bronx Andy King District 12 Bronx James Vacca District 13 Bronx Vanessa Gibson District 16 Bronx Annabel Palma District 18 Bronx Peter Koo District 20 Queens Julissa Ferraras District 21 Queens Costa Constantinides District 22 Queens Mark Weprin District 23 Queens Rory Lancman District 24 Queens Daniel Drumm District 25 Queens Jimmy Van Bramer District 26 Queens Ruben Wills District 28 Queens Elizabeth Crowley District 30 Queens Stephen Levin District 33 Brooklyn Antonio Reynoso District 34 Brooklyn Brad Lander District 39 Brooklyn Mathieu Eugene District 40 Brooklyn Vincent J. Gentile District 43 Brooklyn Jumaane Williams District 45 Brooklyn Alan Maisel District 46 Brooklyn Ari Kagan District 48 Brooklyn Deborah Rose District 49 Staten Island September 2013 . -

Lightsmonday, out February 10, 2020 Photo by Teresa Mettela 50¢ 57,000 Queensqueensqueens Residents Lose Power Volumevolume 65, 65, No

VolumeVol.Volume 66, No. 65,65, 80 No.No. 207207 MONDAY,MONDAY,THURSDAY, FEBRUARYFEBRUARY AUGUST 6,10,10, 2020 20202020 50¢ A tree fell across wires in Queens Village, knocking out power and upending a chunk of sidewalk. VolumeQUEENSQUEENS 65, No. 207 LIGHTSMONDAY, OUT FEBRUARY 10, 2020 Photo by Teresa Mettela 50¢ 57,000 QueensQueensQueens residents lose power VolumeVolume 65, 65, No. No. 207 207 MONDAY,MONDAY, FEBRUARY FEBRUARY 10, 10, 2020 2020 50¢50¢ VolumeVol.VolumeVol.VolumeVol. 66, 66,66, No.65, No. No.65,65, 80No. 80 80194No.No. 207 207207 MONDAY,THURSDAY,MONDAY,MONDAY,THURSDAY,MONDAY, FEBRUARY FEBRUARYFEBRUARY FEBRUARYJANUARY AUGUST AUGUSTAUGUST 6,10,25, 6,10,6,10, 10,2020 202020212020 20202020 50¢50¢50¢ Volume 65, No. 207 MONDAY, FEBRUARY 10, 2020 50¢ VolumeVol.TODAY 66, No.65, 80No. 207 MONDAY,THURSDAY, FEBRUARY AUGUST 6,10, 2020 2020 A tree fell across wires in50¢ TODAY AA tree tree fell fell across across wires wires in in TODAY QueensQueensQueens Village, Village, Village, knocking knocking knocking Nursing home outoutout power power power and and and upending upending upending A treeaa chunka chunkfell chunk across of of ofsidewalk. sidewalk. sidewalk.wires in VolumeVolumeVolumeQUEENSQUEENSQUEENSQUEENS 65, 65,65, No. No.No. 207 207207 LIGHTSLIGHTSduring intenseMONDAY,MONDAY, OUTOUTOUT FEBRUARY FEBRUARYFEBRUARY 10, 10,10, 2020 20202020 vaccineQueensPhotoPhoto PhotoVillage, by bydata byTeresa Teresa Teresa knocking Mettela Mettela Mettela 50¢50¢50¢ QUEENS out power and upending 57,00057,000 Queens QueensQueensQueensQueensQueens -

2020 NYC COUNCIL ENVIRONMENTAL Scorecard Even in the Midst of a Public Health Pandemic, the New York City Council Contents Made Progress on the Environment

NEW YORK LEAGUE OF CONSERVATION VOTERS 2020 NYC COUNCIL ENVIRONMENTAL Scorecard Even in the midst of a public health pandemic, the New York City Council Contents made progress on the environment. FOREWORD 3 The Council prioritized several of the policies that we highlighted in our recent NYC Policy ABOUT THE BILLS 4 Agenda that take significant steps towards our fight against climate change. A NOTE TO OUR MEMBERS 9 Our primary tool for holding Council Members accountable for supporting the priorities KEY RESULTS 10 included in the agenda is our annual New York City Council Environmental Scorecard. AVERAGE SCORES 11 In consultation with our partners from environmental, environmental justice, public LEADERSHIP 12 health, and transportation groups, we identify priority bills that have passed and those we believe have a chance of becoming law for METHODOLOGY 13 inclusion in our scorecard. We then score each Council Member based on their support of COUNCIL SCORES 14 these bills. We are pleased to report the average score for Council Members increased this year and less than a dozen Council Members received low scores, a reflection on the impact of our scorecard and the responsiveness of our elected officials. As this year’s scorecard shows, Council Members COVER IMAGE: ”BRONX-WHITESTONE BRIDGE“ are working to improve mobility, reduce waste, BY MTA / PATRICK CASHIN / CC BY 2.0 and slash emissions from buildings. 2 Even in the midst of a public health pandemic, the New York City Council made progress on the environment. They passed legislation to implement an The most recent City budget included massive e-scooter pilot program which will expand access reductions in investments in greenspaces. -

Queens Town Hall Meeting

The New York City Council SPEAKER MELISSA MARK- VIVERITO Council Member Ydanis Rodriguez Chair, Transportation Committee Council Member Daniel Dromm Council Member Vanessa L. Gibson Council Member Corey Johnson Chair, Education Committee Chair, Public Safety Committee Chair, Health Committee Council Member Jimmy Van Bramer Majority Leader, New York City Council COUNCIL MEMBERS Costa Constantinides, Elizabeth Crowley, Julissa Ferreras, Karen Koslowitz, Peter Koo, Rory Lancman, I. Daneek Miller, Donovan Richards, Eric Ulrich, Paul Vallone, Mark Weprin, Ruben Wills, WITH Queens Borough President Melinda Katz AND The NYC Department of Transportation PRESENT VISION ZERO QUEENS TOWN HALL MEETING WEDNESDAY • APRIL 23RD 2014 • 6:00PM - 8:00PM LaGUARDIA COMMUNITY COLLEGE (The Little Theatre) 31-10 Thomson Avenue, Long Island City 11101 In New York City, approximately 4,000 New Yorkers are seriously injured and more than 250 are killed each year in traffic crashes. The Vision Zero Action Plan is the City’s foundation for ending traffic deaths and injuries on our streets. Vision Zero Will Save Lives – But We Need to Hear From YOU! Come out and give us your feedback, concerns and legislative ideas on Mayor de Blasio’s Vision Zero Plan! We need your ideas to improve street safety, to identify problem locations, and to hammer out site-specific solutions that match realities on the ground. INTERPRETATION SERVICES AVAILABLE IN SPANISH AND MANDARIN. • 現場有囯語翻譯 SERVICIOS DE TRADUCCIÓN DISPONIBLE EN ESPAÑOL Y MANDARÍN. TO RSVP OR FOR MORE INFORMATION, Please call: (212) 341-2644 or email [email protected] . -

Jamaica DRI Plan

DOWNTOWN JAMAICA DOWNTOWN REVITALIZATION INITIATIVE STRATEGIC INVESTMENT PLAN Prepared for the New York State Downtown Revitalization Initiative New York City March 2017 JAMAICA | 1 DRI LOCAL PLANNING COMMITTEE HON. MELINDA KATZ, CO-CHAIR HOPE KNIGHT Borough President President & CEO Queens Greater Jamaica Development Corp. CAROL CONSLATO, CO-CHAIR GREG MAYS Director of Public Affiars, Con Edison Executive Director A Better Jamaica ADRIENNE ADAMS Chair REV. PATRICK O’CONNOR Community Board 12, Queens Pastor First Presbyterian Church in Jamaica CEDRIC DEW Executive Director VEDESH PERSAUD Jamaica YMCA Vice Chairperson Indo-Caribbean Alliance REBECCA GAFVERT Asst. Vice President ROSEMARY REYES NYC EDC Program Manager Building Community Capacity/ DEEPMALYA GHOSH Department of Cultural Affairs Senior Vice President External Affairs & Community Engagement, PINTSO TOPGAY Child Center of New York Director Queens Workforce 1 Center IAN HARRIS Co-Chair DENNIS WALCOTT Jamaica NOW Leadership Council President & CEO Queens Library CATHY HUNG Executive Director CALI WILLIAMS Jamaica Center for Arts & Learning Vice President NYC EDC DR. MARCIA KEIZS President MELVA MILLER York College/CUNY Project Lead Deputy Borough President Office of the Queens Borough President This document was developed by the Jamaica Local Planning Committee as part of the Downtown Revitalization Initiative and was supported by the NYS Department of State, Empire State Development, and Homes and Community Renewal. The document was prepared by the following Consulting Team: HR&A Advisors; Beyer Blinder Belle; Fitzgerald & Halliday, Inc.; Public Works Partners; Parsons Brinkerhoff; and VJ Associates. DOWNTOWN REVITALIZATION INITIATIVE DRI ADVISORY COMMITTEE HON. GREGORY MEEKS MARTHA TAYLOR Congressman Chair Community Board 8, Queens HON. LEROY COMRIE State Senator ISA ABDUR-RAHMAN Executive Director HON. -

Minutes of CSA Executive Board Meeting Wednesday, June 6, 2017

Minutes of CSA Executive Board Meeting Wednesday, June 6, 2017 Excused: Allan Baldassano; Susan Barone; Justin Berman; Darlene Cameron; Dominick D’Angelo; Raymond Granda; Barbara Hanson; Joseph Mannella; Rhonda Phillips; Philip Santos; Edward Tom; Michael Troy; Denise Watson; Mark Goldberg; Antonio Hernandez; Roseann Napolitano; Marie Polinsky Absent: Andrew Frank; Heather Leykam; Clemente Lopes; Christine Mazza; Randy Nelson; David Newman; Michael Ranieri; Hally Tache-Hahn; Santosha Toutman; Christopher Warnock; Stephen Beckles; Patricia Cooper; Steve Dorcley; Joseph Lisa; Katiana Louissaint; Neil McNeil; Robert Mercedes; John Norton; Maria Nunziata; Glen Rasmussen; Debra Rudolph The meeting was called to order by Ernest Logan at 5:05 PM. 1. The minutes of the May 17, 2017 meeting were accepted as written. 2. PRESIDENT’S REPORT – Ernest A. Logan 2.1 Announcement – Ernest A. Logan announced that he will retire as CSA President on August 31, 2017. He looks forward to doing work on a national level with AFSA and National AFL-CIO. He asks that you support Mark and the leadership team as you supported him. 3. EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT REPORT – Mark F. Cannizzaro 3.1 Mark announced EA victory shared few details on the victory. Thanked everyone for support and wished everyone a great summer. 4. FIRST VICE PRESIDENT’S REPORT – Henry Rubio 4.1 School Budget – Henry touched on school budget and asks that you please contact him with questions. He also wished everyone a relaxing summer. 5. LEGAL REPORT – David Grandwetter 5.1 EA Cases – David went over the EA settlement in detail and announced the contractual raises are to be paid in September and October. -

Reshaping New York Report Page 1

Citizens Union of the City of New York November 2011 Reshaping New York Report Page 1 Appendix 1 1a. Nesting of New York City Assembly Districts in Senate Districts After 2002 Redistricting Cycle NESTING OF NEW YORK CITY’S ASSEMBLY DISTRICTS IN SENATE DISTRICTS Assembly Districts Number of Nested Senate District (By District Number) Assembly Districts 10 23, 25, 27, 28, 29, 31, 32, 33, 38 9 11 22, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29, 31, 33 8 12 30, 34, 36, 37, 38 5 13 34, 35, 37, 39 4 14 23, 24, 25, 27, 29, 31, 33 7 15 23, 28, 30, 37, 38 5 16 22, 24, 25, 26, 27 5 17 40, 50, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57 7 18 44, 50, 51, 52, 54, 55, 56, 57 8 19 40, 41, 42, 43, 55, 58, 59 7 20 42, 43, 44, 51, 52, 55, 56, 57, 58 9 21 41, 42, 43, 44, 48, 51, 58, 59 8 22 41, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 51, 59, 60 9 23 46, 47, 48, 49, 51, 60, 61, 63 8 24 60, 61, 63, 62 4 25 50, 52, 57, 64, 66, 74 6 26 65, 67, 69, 73, 74, 75 6 27 41, 45, 47, 49, 44, 48 7 28 65, 68, 73, 84, 86 5 29 66, 67, 74, 75 4 30 67, 68, 69, 70 4 31 67, 69, 70, 71, 72, 78, 81 7 32 76, 79, 80, 82, 84, 85 6 33 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 86 6 34 76, 80, 82, 83 4 36 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 86 9 Appendix 1 ‐ 1 Citizens Union of the City of New York November 2011 Reshaping New York Report Page 2 1b. -

Via Electronic and U.S. Mail December 31, 2015

Via Electronic and U.S. Mail December 31, 2015 Bill de Blasio Mayor City Hall New York, NY 10007 Dear Mayor de Blasio: We write to encourage you to ask your administrative agencies to identify 5% in potential savings for Fiscal Year 2017 before you issue the Preliminary Budget. This is an important exercise to ensure that agencies are operating at their most efficient, and that there is minimal waste. Beginning in 1982, prior administrations made a point to incorporate gap closing measures into yearly, city wide funding plans -- whether or not a budget deficit was anticipated for the current year. Identifying savings has the benefit of contributing to the City’s financial stability by helping to cover gaps in current or future budgets by paring down agency spending, and avoiding the need for revenue-raising measures. A City Council examination of the budget from April of this year reports that the City achieved a balanced budget in Fiscal Year 2015 and will do the same in Fiscal Year 2016. That same report, however, also shows a projected budget gap of $1.05 billion beginning in Fiscal Year 2017, and growing to a gap of $2.07 billion in Fiscal Year 2019. After two years of experience, your agency heads should be asked to identify those policies that are either not working, or unnecessary. Freeing up funds could allow us to either address other funding priorities, to save for future obligations, or even to relieve tax burdens on small businesses or homeowners. Conducting this kind of financial analysis is good policy. -

Transcript of the Minutes

1 CITY COUNCIL CITY OF NEW YORK ------------------------ X TRANSCRIPT OF THE MINUTES Of the COMMITTEE ON FIRE AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE SERVICES JOINTLY WITH COMMITTEE ON CONTRACTS AND COMMITTEE ON WOMEN’S ISSUES ------------------------ X December 10, 2014 Start: 10:24 a.m. Recess: 03:14 p.m. HELD AT: Council Chambers – City Hall B E F O R E: ELIZABETH S. CROWLEY Chairperson HELEN K. ROSENTHAL Co-Chairperson LAURIE A. CUMBO Co-Chairperson COUNCIL MEMBERS: FERNANDO CABRERA MATHIEU EUGENE PAUL A. VALLONE RORY I. LANCMAN CHAIM M. DEUTSCH COREY D. JOHNSON COSTA G. CONSTANTINIDES I. DANEEK MILLER PETER A. KOO World Wide Dictation 545 Saw Mill River Road – Suite 2C, Ardsley, NY 10502 Phone: 914-964-8500 * 800-442-5993 * Fax: 914-964-8470 www.WorldWideDictation.com 2 COUNCIL MEMBERS: (CONTINUED) RUBEN WILLS BEN KALLOS DARLENE MEALY KAREN KOSLOWITZ 3 A P P E A R A N C E S (CONTINUED) COMMITTEE ON FIRE AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE SERVICES JOINTLY WITH 1 COMMITTEE ON CONTRACTS AND COMMITTEE ON WOMEN’S ISSUES 4 2 [gavel] 3 CHAIRPERSON CROWLEY: Good morning. My 4 name is Elizabeth Crowley and I am the Chair of the 5 Fire and Criminal Justice Services Committee. Today 6 the committee is conducting a follow-up hearing on 7 last year’s oversight hearing in our ongoing effort 8 to get to the root behind the troubling lack of 9 women firefighters in our city’s fire department. 10 The hearing is being conducted jointly with the 11 Committee on Contracts which is chaired by Council 12 Member, Council Member Helen Rosenthal and the 13 Committee on Women’s Issues which is chaired by 14 Council Member Laurie Cumbo. -

THE COUNCIL Minutes of the Proceedings for the STATED MEETING of Wednesday, November 28, 2018, 1:49 P.M. the Majority Leader (C

THE COUNCIL Minutes of the Proceedings for the STATED MEETING of Wednesday, November 28, 2018, 1:49 p.m. The Majority Leader (Council Member Cumbo) presiding as the Acting President Pro Tempore Council Members Corey D. Johnson, Speaker Adrienne E. Adams Robert F. Holden Helen K. Rosenthal Alicia Ampry-Samuel Ben Kallos Rafael Salamanca, Jr Diana Ayala Karen Koslowitz Ritchie J. Torres Inez D. Barron Rory I. Lancman Mark Treyger Joseph C. Borelli Bradford S. Lander Eric A. Ulrich Justin L. Brannan Stephen T. Levin Paul A. Vallone Fernando Cabrera Alan N. Maisel James G. Van Bramer Margaret S. Chin Steven Matteo Jumaane D. Williams Andrew Cohen Carlos Menchaca Kalman Yeger Laurie A. Cumbo I. Daneek Miller Chaim M. Deutsch Francisco P. Moya Ruben Diaz, Sr. Keith Powers Daniel Dromm Antonio Reynoso Rafael L. Espinal, Jr Donovan J. Richards Mathieu Eugene Carlina Rivera Mark Gjonaj Ydanis A. Rodriguez Barry S. Grodenchik Deborah L. Rose Absent: Council Members Constantinides, Cornegy, Gibson, King, Koo, Levine and Perkins. The Majority Leader (Council Member Cumbo) assumed the chair as the Acting President Pro Tempore and Presiding Officer for these proceedings. The Public Advocate (Ms. James) was not present at this Meeting. After consulting with the City Clerk and Clerk of the Council (Mr. McSweeney), the presence of a quorum was announced by the Majority Leader and Acting President Pro Tempore (Council Member Cumbo). 4430 November 28, 2018 There were 44 Council Members marked present at this Stated Meeting held in the Council Chambers of City Hall, New York, N.Y. INVOCATION The Invocation was delivered by Reverend Dr.