John Waters: Camp, Abjection and the Grotesque Body

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subcultural Appropriations of Appalachia and the Hillbilly Image, 1990-2010

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2019 The Mountains at the End of the World: Subcultural Appropriations of Appalachia and the Hillbilly Image, 1990-2010 Paul L. Robertson Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Appalachian Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons © Paul L. Robertson Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/5854 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robertson i © Paul L. Robertson 2019 All Rights Reserved. Robertson ii The Mountains at the End of the World: Subcultural Appropriations of Appalachia and the Hillbilly Image, 1990-2010 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University. By Paul Lester Robertson Bachelor of Arts in English, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2000 Master of Arts in Appalachian Studies, Appalachian State University, 2004 Master of Arts in English, Appalachian State University, 2010 Director: David Golumbia Associate Professor, Department of English Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2019 Robertson iii Acknowledgement The author wishes to thank his loving wife A. Simms Toomey for her unwavering support, patience, and wisdom throughout this process. I would also like to thank the members of my committee: Dr. David Golumbia, Dr. -

Configuring a Scatological Gaze in Trash Filmmaking Zoe Gross

Excremental Ecstasy, Divine Defecation and Revolting Reception: Configuring a Scatological Gaze in Trash Filmmaking Zoe Gross Scatology, for all the sordid formidability the term evokes, is not an es- pecially novel or unusual theme, stylistic technique or descriptor in film or filmic reception. Shit happens – to emphasise both the banality and perva- siveness of the cliché itself – on multiple levels of textuality, manifesting it- self in both the content and aesthetic of cinematic texts, and the ways we respond to them. We often refer to “shit films,” using an excremental vo- cabulary redolent of detritus, malaise and uncleanliness to denote their otherness and “badness”. That is, films of questionable taste, aesthetics, or value, are frequently delineated and defined by the defecatory: we describe them as “trash”, “crap”, “filth”, “sewerage”, “shithouse”. When considering cinematic purviews such as the b-film, exploitation, and shock or trash filmmaking, whose narratives are so often played out on the site of the gro- tesque body, a screenscape spectacularly splattered with bodily excess and waste is de rigeur. Here, the scatological is both often on blatant dis- play – shit is ejected, consumed, smeared, slung – and underpining or tinc- turing form and style, imbuing the text with a “shitty” aesthetic. In these kinds of films – which, as their various appellations tend to suggest, are de- fined themselves by their association with marginality, excess and trash, the underground, and the illicit – the abject body and its excretia not only act as a dominant visual landscape, but provide a kind of somatic, faecal COLLOQUY text theory critique 18 (2009). -

Outrageous Opinion, Democratic Deliberation, and Hustler Magazine V

VOLUME 103 JANUARY 1990 NUMBER 3 HARVARD LAW REVIEW THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONCEPT OF PUBLIC DISCOURSE: OUTRAGEOUS OPINION, DEMOCRATIC DELIBERATION, AND HUSTLER MAGAZINE V. FALWELL Robert C. Post TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. HUSTLER MAGAZINE V. FALWELL ........................................... 6o5 A. The Background of the Case ............................................. 6o6 B. The Supreme Court Opinion ............................................. 612 C. The Significance of the Falwell Opinion: Civility and Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress ..................................................... 616 11. THE FIRST AMENDMENT AND PUBLIC DISCOURSE ............................. 626 A. Public Discourse and Community ........................................ 627 B. The Structure of Public Discourse ............... ..................... 633 C. The Nature of Critical Interaction Within Public Discourse ................. 638 D. The First Amendment, Community, and Public Discourse ................... 644 Im. PUBLIC DISCOURSE AND THE FALIWELL OPINION .............................. 646 A. The "Outrageousness" Standard .......................................... 646 B. The Distinction Between Speech and Its Motivation ........................ 647 C. The Distinction Between Fact and Opinion ............................... 649 i. Some Contemporary Understandings of the Distinction Between Fact and Opinion ............................................................ 650 (a) Rhetorical Hyperbole ............................................. 650 (b) -

New World Documentaries

January / February 2014 www.winnipegcinematheque.com New World Documentaries Doc’s joyous, romantic, heartbreaking and extraordinarily eventful journey. In his later years, Doc was a mentor to generations of younger songwriters and a fierce advocate for downtrodden musicians. He wrote a thousand songs – including some of the most recorded songs in the history of popular music – but his most lasting gift may have been his uniquely generous spirit. Passages from Doc’s private journals are read by his close friend, Lou Reed. When Jews Were Funny Directed by Alan Zweig 2013, Canada, 90 min Friday, January 10 / 9 pm Saturday – Sunday, January 11 – 12 / 7 pm Wednesday – Friday, January 15 – 17 / 7 pm Saturday, January 18 / 9 pm Best Canadian Feature: 2013 Toronto International Film Festival “The film begins with a question: Why were so many comedians Zweig watched on television in the 1950’s and 60’s Jewish? Zweig presents a casual first person history of Jewish stand up, unearthing some amazing ↑ The Summit archival footage (with a phemonenal bit by the legendary Jackie Mason) and interviewing The Summit some of America’s most successful and Directed by Nick Ryan influential comics, including Elon Gold, Howie 2012, USA, 99 min Mandel, Shelly Berman, Jack Carter, Shecky Greene, David Steinberg and Super Dave Friday – Sunday, January 3 – 5 / 7 pm Osborne… funny and heartfelt.”—TIFF Wednesday – Thursday, January 8 – 9 / 7 pm “Hilarious from start to finish, and at times K2 in the Himalayas is known to climbers very touching.”— THE FILM REEL as the most difficult of mountains, a savage peak, the second highest in the world, with the Insightful and often hilarious, the latest from power to cloud men’s minds. -

Session Yields Pay Raises, Additional Funds

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar The Parthenon University Archives Fall 9-6-1990 The Parthenon, September 6, 1990 Marshall University Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon Recommended Citation Marshall University, "The Parthenon, September 6, 1990" (1990). The Parthenon. 2819. https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon/2819 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Parthenon by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ---------------- - M Or $h U II Univ e rsity .•~ ====r=-===--. -~~- Vol 9 1 No 1 Hut1 l1 ngt o n V/ Vo H1U rsdc1y , Sept .. 6 . 1990 - . - Session yields pay raises, additional funds By Susan Douglas Hahn · in addition to the September $1,000 increase. major portion of the funding will be allocated to programs The Legislature allocated approximately $ 3. 7 million to Senior Coffespondent in higher education that need additional funding for ac the Board of Trustees to fund the pay increases. creditation or certification and EPSCoR, a federal program Actions during the recent special session for education Marshall also will receive part of$2.9 million, which has that offers matching funds for research development. will provide funding for faculty salary increases, accredita been earmarked by the Legislature to be distributed by the Marshall, West Virginia University, and West Virginia tion and research development. Department ofEducation and the Arts for scholarships, in Institute of Technology are involved in EPSCoR (Experi Faculty members, who received pay raises in July and field master's programs, acc,-editation of existing pro mental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research). -

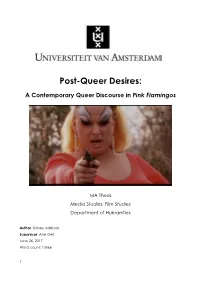

Post-Queer Desires

Post-Queer Desires: A Contemporary Queer Discourse in Pink Flamingos MA Thesis Media Studies: Film Studies Department of Humanities Author: Sidney Adelaar Supervisor: Abe Geil June 26, 2017 Word count: 13566 1 2 Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………. p. 5 1. The Anti-Social Queer Desiring-Machine: Going Beyond Queer………... p. 11 1.1 Antisocial Filth……………………………………………………………... p. 12 1.2 The Queer Desiring-Machine…………………………………………… p. 15 1.3 Desiring...Poop?…………………………………………………………... p. 19 2. Celebrating a Post-Queer Utopia or Dystopia?……………………………… p. 24 2.1 A Mudgey Dystopia……………………………………………………… p. 24 2.2 A Divine Utopia……………………………………………………………. p. 27 2.3 A Happy Post-Queer Birthday, Divine!………………………………... p. 30 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………… p. 37 Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………….. p. 40 Appendix……………………………………………………………………………….. p. 41 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………. p. 44 Films Cited……………………………………………………………………………… p. 45 3 4 Introduction Queer cinema is a fairly recent category in cinema history. Starting around 30 years ago, during the same time in the 1980’s that queer theory became a prominent academic discipline, queer cinema seems to encompass all films that deal with gay and lesbian themes, or ‘LGBT’ to use a recent term. As these themes focus mainly on the sexuality of the characters and their struggles in a ‘straight’ world because of it, there appears to be a major centring around desires, be it sexual or something else. If a desire is not desirable in heteronormative society, ‘queer’ is the right word for it. This thesis’ main focus is this notion of queer desires. By focusing on this aspect of the queer, I will show just how these desires can shape queer cinema and provide a unique framework for the analysis of the modern queer film. -

September 23, 2011 | Volume IX Issue 10 CHA-CHA HEELS, LIQUID EYELINER, AND

OUT September 23, 2011 | Volume IX Issue 10 CHA-CHA HEELS, LIQUID EYELINER, AND... The Most Beautiful Woman in the World B y chucK Duncan If you’re a native of Baltimore (and even if you’re not), you certainly know John Waters and Divine. From John’s ear- ly short films from the late 60s to his 1972 calling card, Emmett C. Burns, Pink Flamingos, through 1988’s Hairspray, Waters and his Jr., Announces PAC muse Divine showed the rest of the world what the “reel” to Oppose Marriage Baltimore was like (and there was more than a little of the “real” in those films too). Equality Unfortunately, shortly after the release of Hairspray, Divine passed away suddenly at the true By Dana LaRocca height of his career (he was in Hollywood On September 9, Delegate Emmett C. Susan Lowe, preparing to tape an episode of Married Burns, Jr. (D-Baltimore County) met Mink Stole and Jeffrey … with Children at the time of his death), with eight other clergy at a church in Schwarz depriving the world of his talent and what west Baltimore to announce the for- during their might have come from his true “overnight” mation of “Progressive Clergy in interview stardom. Action” a political action committee. sessions in Today, Divine is a cult figure to many, The group is working with the help of Baltimore his legion of fans from around the world the Maryland Family Alliance, an af- photo: courtesy of Jeffrey Schwarz —continued on page 16 filiate of the Family Research Council (FRC). Delegate Burns has long been and Developed by a Combined Arms Center- an opponent of marriage equality. -

The Gay Revolution and the Pink Flamingos Bachelor’S Diploma Thesis

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jiří Vrbas The Gay Revolution and the Pink Flamingos Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: doc. Michael Matthew Kaylor, PhD. 2016 1 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. ………………………………………………. 2 “I thank God I was raised Catholic, so sex will always be dirty.” (John Waters) Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor doc. Michael Matthew Kaylor, PhD, for his help and for making me believe in this topic. I would also like to thank him and Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, BA, alike for their Gay Studies course. Knowledge acquired in their class provided the necessary background for this analysis. 3 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 5 I. Being Gay in the Past .................................................................................................. 7 I.1. 18th Century Europe ................................................................................................ 7 I.2. The Early 20th Century USA .................................................................................. 9 I.3. The 1950s USA .................................................................................................... 14 II. Early Gay Rights Activism .................................................................................... -

Thesis John Waters

john waters: subversive success interview with wall street journal By John Jurgensen John Waters, the writer and director who emerged from the midnight movie circuit of the 1970s, has earned his status as a social critic. In 13 feature films, including Pink Flamingos and Hairspray, he gleefully presents depraved characters undermining a society of squares. In the seven years since he made his last film, the director has written Role Models, a collection of essays about his idols who hurdled over adversity, including Johnny Mathis, Little Richard and a seedy pornographer. He’s also hunting down funding for his next script, Fruitcake, a Christmas movie for kids. He lives in Baltimore, his native city and the setting for his films, in a house purchased in 1990. At age 65, Waters remains a celebrated figure for counterculturists but accepts that his time as a revolutionary has passed. Earlier this year, protestors at Occupy Baltimore built an encampment they called Mortville, a tribute to the criminal enclave depicted in Waters’s film Desperate Living. Waters supports them but declined to join. “I have three homes and a summer rental, and some of my money is in Wall Street,” he explained. He champions younger filmmakers whom he says succeed in subversion, including Johnny Knoxville and Todd Phillips. At the same time, he reviles “the new bad taste,” which he defines as entertainment that tries too hard to shock and lacks inventiveness and wit. When I was a kid, my parents were a little uptight because the things I was interested in weren’t the proper things for a six-year-old. -

Nan Goldin and Andres Serrano's Post-Mortem Photography

Visible Care: Nan Goldin and Andres Serrano’s Post-mortem Photography Lauren Jane Summersgill Humanities and Cultural Studies Birkbeck, University of London Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 2 Declaration I certify that this thesis is the result of my own investigations and, except for quotations, all of which have been clearly identified, was written entirely by me. Lauren J. Summersgill October 2014 3 Abstract This thesis investigates artistic post-mortem photography in the context of shifting social relationship with death in the 1980s and 1990s. Analyzing Nan Goldin’s Cookie in Her Casket and Andres Serrano’s The Morgue, I argue that artists engaging in post- mortem photography demonstrate care for the deceased. Further, that demonstrable care in photographing the dead responds to a crisis of the late 1980s and early 1990s in America. At the time, death returned to social and political discourse with the visibility of AIDS and cancer and the euthanasia debates, spurring on photographic engagement with the corpse. Nan Goldin’s 1989 post-mortem portrait of her friend, Cookie in Her Casket, was first presented within The Cookie Portfolio. The memorial portfolio traced the friendship between Cookie and Goldin over fourteen years. The work relies on a personal narrative, framing the works within a familial gaze. I argue that Goldin creates the sense of family to encourage empathy in the viewer for Cookie’s loss. Further, Goldin’s generic and beautified post-mortem image of Cookie is a way of offering Cookie respect and dignity in death. Andres Serrano’s 1992 The Morgue is a series of large-scale cropped, and detailed photographs capturing indiscriminate bodies from within an unidentified morgue. -

John Waters (Writer/Director)

John Waters (Writer/Director) Born in Baltimore, MD in 1946, John Waters was drawn to movies at an early age, particularly exploitation movies with lurid ad campaigns. He subscribed to Variety at the age of twelve, absorbing the magazine's factual information and its lexicon of insider lingo. This early education would prove useful as the future director began his career giving puppet shows for children's birthday parties. As a teen-ager, Waters began making 8-mm underground movies influenced by the likes of Jean-Luc Godard, Walt Disney, Andy Warhol, Russ Meyer, Ingmar Bergman, and Herschell Gordon Lewis. Using Baltimore, which he fondly dubbed the "Hairdo Capitol of the World," as the setting for all his films, Waters assembled a cast of ensemble players, mostly native Baltimoreans and friends of long standing: Divine, David Lochary, Mary Vivian Pearce, Mink Stole and Edith Massey. Waters also established lasting relationships with key production people, such as production designer Vincent Peranio, costume designer Van Smith, and casting director Pat Moran, helping to give his films that trademark Waters "look." Waters made his first film, an 8-mm short, Hag in a Black Leather Jacket in 1964, starring Mary Vivian Pearce. Waters followed with Roman Candles in 1966, the first of his films to star Divine and Mink Stole. In 1967, he made his first 16-mm film with Eat Your Makeup, the story of a deranged governess and her lover who kidnap fashion models and force them to model themselves to death. Mondo Trasho, Waters' first feature length film, was completed in 1969 despite the fact that the production ground to a halt when the director and two actors were arrested for "participating in a misdemeanor, to wit: indecent exposure." In 1970, Waters completed what he described as his first "celluloid atrocity," Multiple Maniacs. -

JOHN WATERS Born 1946 Lives and Works in Baltimore, MD SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 John Waters

JOHN WATERS Born 1946 Lives and works in Baltimore, MD SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 John Waters: Indecent Exposure, Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD, (traveled to Columbus, OH, Wexner Center for the Arts) 2016 BLACK BOX: KIDDIE FLAMINGOS, Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD, curated by Kristen Hileman 2015 How much can you take?, Kunsthaus Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland Beverly Hills John, London, UK, Sprüth Magers 2015 Beverly Hills John, Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, NY 2014 Sprüth Magers, Berlin, February 2014 2012 John Waters: Neurotic, McClain Gallery, Houston, TX 2011 John Waters, Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans, LA 2010 Outsider Porn: The Photos of David Hurles, Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, Project Space Exhibition curated by John Waters Rush, Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco, CA C. Grimaldis Gallery, Baltimore, MD 2009 Neurotic, Albert Merola Gallery, Provincetown, MA Rear Projection, Gagosian Gallery, Los Angeles Rear Projection, Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York 2008 Artistically Incorrect: The Photographs and Sculpture of John Waters, Laumeier Sculpture Park, St. Louis, MO 2007 Reckless Eyeballs, Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco, CA 2006 Eat Me, Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans, LA 21c Museum Hotel, Louisville, KY Albert Merola Gallery, Provincetown, MA Unwatchable, Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, and de Pury & Luxembourg, Zurich The Visual Arts Gallery, The University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 2005 Condemned, Albert Merola Gallery, Provincetown, MA John Waters: Greatest Hits