UCL Urban Migration Film Festival and Symposium Summary Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Event Sponsors

City of Falls Church Schedule of Events Easter Egg Hunt Cherry Hill Park, Saturday prior to Easter, 10am Partner with the City Art Show & Sale Falls Church Community Center, fourth Friday and Saturday in April Friday 5-7pm, Saturday 12-4pm City of Falls Church Farmers’ Market Located only six miles from the Nation’s Capital City Hall Parking Lot, Saturdays year round and inside the Capital Beltway, the City of Falls Summer/Spring 8am-12noon, Winter 9am-12noon Church is a wonderful place to live, work and Civil War Reenactment visit, offering diversity in housing, amenities and Cherry Hill Park, third Saturday in May, 10am-3pm services. Its historic charm reflects the stewardship Memorial Day Parade & Festival of residents and their local government. Visitors and City Hall Grounds, Memorial Day, 9am-5pm residents alike can find everything they need while experiencing the fabric of like in a friendly, close Concerts in the Park Cherry Hill Park, select Thursdays June-August, 7pm knit-community. Independence Day Celebration Recreation and Parks Falls Church became a township in 1875 and then an George Mason High School, July 4th, 7pm independent city in 1948. The City is easily accessible Sunset Cinema by both East Falls Church and West Falls Church Cherry Hill Park, select Fridays in August, 8:30pm Metro stations, several bus routes and Interstate 66. Sponsorship Falls Church City takes pride in its long standing We invite you to become a partner with the City of Fall Festival & Taste of Falls Church tradition of community wide events. Residents and Falls Church in offering one or several of these special Cherry Hill Park, select Saturday in September, 10am-4pm visitors alike turn out for our family friendly events events. -

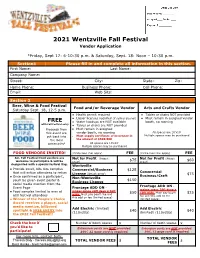

2021 Fall Festival Vendor Application

2021 Wentzville Fall Festival Vendor Application *Friday, Sept 17: 6-10:30 p.m. & Saturday, Sept. 18: Noon – 10:30 p.m. Section1 Please fill in and complete all information in this section. First Name: Last Name: Company Name: Street: City: State: Zip: Home Phone: Business Phone: Cell Phone: Email: Web Site: Section 2 Beer, Wine & Food Festival Food and/or Beverage Vendor Arts and Crafts Vendor Saturday Sept. 18, 12-5 p.m. ● Health permit required ● Tables or chairs NOT provided ● Liquor licenses required (if selling alcohol) ● Must remain in assigned vendor FREE ● Water hookups are NOT available booth, no roaming with Fall Festival entry ● Tables or chairs are NOT provided Proceeds from ● Must remain in assigned this event are vendor booth, no roaming All spaces are 10’x10’ put back into ● Must supply certificate of insurance in Multiple spaces may be purchased the local the amount of $500,000 community! All spaces are 10’x10’ Multiple spaces may be purchased FOOD VENDORS INVITED! (Circle fees that apply) FEE (Circle fees that apply) FEE ALL Fall Festival food vendors are Not for Profit (Attach $75 Not for Profit (Attach $60 welcome to participate & will be proof) proof) designated with a special festival flag. Wentzville ● Provide small, bite size samples Commercial/Business $125 Commercial that will entice attendees to return License (Attach proof) $75 Business/Craft ● Once confirmed as a participant, Non-Wentzville $150 you’ll be given event poster & Business License social media mention from the Frontage ADD ON - Event Page Frontage ADD ON - makes space 20ft deep x makes space 20ft deep x 10ft ● Food samples limited to max of $50 10ft wide. -

Party City’S December 31, 2015 Form 10-K and in Subsequent Reports Filed with Or Furnished to the SEC

5.10 4.50 - logo 0.15 0.15 5.10 2.60 Bank of America Merrill Lynch Consumer & Retail Technology Conference 1.80 March 15, 2016 2.15 3.30 3.75 Disclaimer Forward Looking Statements Certain statements herein are ―forward-looking statements‖ made pursuant to the safe harbor provisions of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. Statements contained herein that are not clearly historical in nature are forward-looking. In many cases, you can identify forward-looking statements by terms such as ―may,‖ ―will,‖ ―should,‖ ―expects,‖ ―plans,‖ ―anticipates,‖ ―believes,‖ ―estimates,‖ ―predicts,‖ ―potential‖, ―targets‖, ―intends‖ or the negative of these terms or other comparable terminology. These forward-looking statements speak only as of the date hereof and are based on the Company’s current plans and expectations and are subject to a number of known and unknown uncertainties and risks, many of which are beyond the Company’s control. These risks and uncertainties include: our ability to compete effectively in a competitive industry; fluctuations in commodity prices; our ability to appropriately respond to changing merchandise trends and consumer preferences; successful implementation of our store growth strategy; decreases in our Halloween sales; disruption to the transportation system or increases in transportation costs; product recalls or product liability; economic slowdown affecting consumer spending and general economic conditions; loss or actions of third party vendors and loss of the right to use licensed material; disruptions at our manufacturing facilities; and the additional risk and uncertainties set forth in ―Risk Factors‖ in Party City’s December 31, 2015 Form 10-K and in subsequent reports filed with or furnished to the SEC. -

Harvest Ceremony

ATLANTIC OCEAN PA\\' fl.. Xf I I' I \ f 0 H I PI \ \. I \I ION •,, .._ "', Ll ; ~· • 4 .. O\\'\\1S s-'' f1r~~' ~, -~J.!!!I • .. .I . _f' .~h\ ,. \ l.J rth..i'i., \ inc-v •.u d .. .. .... Harvest Ceremony BEYOND THE THANK~GIVING MYTH - a study guide Harvest Ceremony BEYOND THE THANKSGIVING MYTH Summary: Native American people who first encountered the “pilgrims” at what is now Plymouth, Massachusetts play a major role in the imagination of American people today. Contemporary celebrations of the Thanksgiving holiday focus on the idea that the “first Thanksgiving” was a friendly gathering of two disparate groups—or even neighbors—who shared a meal and lived harmoniously. In actuality, the assembly of these people had much more to do with political alliances, diplomacy, and an effort at rarely achieved, temporary peaceful coexistence. Although Native American people have always given thanks for the world around them, the Thanksgiving celebrated today is more a combination of Puritan religious practices and the European festival called Harvest Home, which then grew to encompass Native foods. The First People families, but a woman could inherit the position if there was no male heir. A sachem could be usurped by In 1620, the area from Narragansett Bay someone belonging to a sachem family who was able in eastern Rhode Island to the Atlantic Ocean in to garner the allegiance of enough people. An unjust or southeastern Massachusetts, including Cape Cod, unwise sachem could find himself with no one to lead, Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, was the home as sachems had no authority to force the people to do of the Wampanoag. -

Religious Festival Marketing: Distinguishing Between Devout Believers and Tourists

religions Article Religious Festival Marketing: Distinguishing between Devout Believers and Tourists Kuo-Yan Wang 1 , Azilah Kasim 2,* and Jing Yu 1 1 Department of Marketing in School of Economics and Management, Guangdong University of Petrochemical Technology, Maoming 525000, China; [email protected] (K.-Y.W.); [email protected] (J.Y.) 2 School of Tourism, Hospitality & Event Management, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Sintok 06010, Malaysia * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 July 2020; Accepted: 10 August 2020; Published: 12 August 2020 Abstract: Customer classification is an integral part of marketing planning activities. Researchers have struggled to classify “pilgrims” and “tourists” because these groups overlap to a large extent in terms of their identities while participating in religious activities/sightseeing. To achieve sustainable tourism development for the region with rich religious and cultural characteristics, the present article outlines a process for analyzing the motivation of participants attending religious festival of Mazu in Taiwan and then classifies religious festival participants according to their motivations. Using cluster sampling, a total of 280 responses were obtained and analyzed. The results revealed four different motivation categories: Fun traveler, devout believer, cultural enthusiast, and religious pragmatist. The study concludes that while festivalgoers are influenced by secularization to some extent, the original doctrine of the religion epitomized in the festivals fundamentally retains the essence and spirit of its religious rituals. The findings may have a significant value for the development of religious tourism marketing as it offers a foundation for future research seeking to develop regional cultural and religious sightseeing attractions sustainably. Keywords: festival; customer classification; factor analysis; motivation; folklore belief 1. -

A Thanksgiving Hymn Festival November 22, 2020

A Thanksgiving Hymn Festival November 22, 2020 Now Thank We All Our God Jamie Council Garvey, Sawyer Branham, Abraham Hardy, Elizabeth Lee, Brian Woods-Lustig Introduction by Jamie Council Garvey, director of Concerts with a Cause Come, Ye Thankful People, Come Keith Shafer, Sawyer Branham, Abraham Hardy, Elizabeth Lee, Brian Woods-Lustig Postlude on St. George's Windsor Keith Shafer by Alan Bullard Gratitude Betty Walpert by Henry van Dyke A Simple Thanksgiving Larry Millen, Anastasia Petrunina, Rich Bias, arr. Joseph Martin Sawyer Branham, Corey Grant, Megan Hoglund, Elizabeth Lee Simple Gifts Clara Park, Martin David Jones arr. Martin David Jones On Thy Wondrous Works I Will Carol Capers Meditate v.8 (Psalm 145) by Mary Oliver For the Fruits of This Creation Rich Bias, Sawyer Branham, Corey Grant, arr. Joseph Martin Megan Hoglund, Elizabeth Lee For the Fruits of This Creation Chris Connelly, Larry Millen, Anastasia Petrunina arr. Larry Shackley/David Milligan i thank You God for most this amazing Jim Garvey by e.e. cummings Grateful Sawyer Branham, John Bucchino by John Bucchino Merry Autumn Nichole Kuehl by Paul Laurence Dunbar Praise to the Lord, the Almighty Alvin Blount, Sawyer Branham, Abraham Hardy, Elizabeth Lee, Brian Woods-Lustig Praise to the Lord, the Almighty Alvin Blount arr. John Carter from The Adventures of Roy Lewis Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain Megan Hoglund, director of St. John Cherub Choir Let All Things Now Living Jamie Council Garvey, Christine Hoglund, arr. David Cherwien Megan Hoglund, Larry Millen Hungry Mungry Kenya Solomon by Shel Silverstein O God, Our Help in Ages Past Brad Cunningham, Sawyer Branham, Abraham Hardy, Elizabeth Lee, Brian Woods-Lustig Chorale Prelude on St. -

KETV FAMILY FESTIVAL SHOWCASES DOWNTOWN ATTRACTIONS with AFTERNOON of FREE ADMISSION and ACTIVITIES for ALL AGES Crafts, Music and Holiday Fun Featured at Six Venues

Media Contact: Kylie Vonnahme, Vic Gutman & Associates: (402) 345-5401 ext. 117, [email protected] Onsite Event Contact: (402) 841-2560 KETV FAMILY FESTIVAL SHOWCASES DOWNTOWN ATTRACTIONS WITH AFTERNOON OF FREE ADMISSION AND ACTIVITIES FOR ALL AGES Crafts, Music and Holiday Fun Featured at Six Venues (OMAHA, Neb.) Nov. 14, 2019 – The Holiday Lights Festival and KETV Channel 7, Omaha’s News Leader, is proud to present Omaha-area families with the opportunity to experience an afternoon of fun— for free—at a variety of Omaha’s leading downtown attractions. This year’s Family Festival, sponsored by Lincoln Financial Group, will be held Sunday, Dec. 1, from noon to 5 p.m. Families can park at any of the six participating venues to access a free heated trolley service provided by Ollie the Trolley to connect the sites. All offer free admission and family activities. The KETV Family Festival is part of the series of events comprising the annual Holiday Lights Festival. Families are encouraged to “Shine the Light on Hunger” and donate nonperishable foods and household goods to be distributed to children and families in need through Food Bank for the Heartland. Most participating Family Festival venues will host a food collection barrel or bin. “The KETV Channel 7 team is excited to present the Family Festival again this year,” said Ariel Roblin, KETV’s president and general manager. “Laying down roots in any community has a lot to do with the traditions we celebrate together. The Family Festival has become an annual tradition for many area families. It’s the fun and heartwarming traditions like these that make Omaha home for so many” The 2019 Family Festival will feature the following attractions and special programs at these locations: Omaha Children’s Museum, 500 S. -

2020 Interfaith Calendar Holidays & Festivals

2020 Interfaith Calendar Holidays & Festivals We are a human relations organization dedicated to achieving respect and understanding for all through education and dialogue. OCCJ seeks to facilitate understanding and empower individuals to create inclusive communities through dynamic, diversity and inclusion programming for all ages. www.occjok.org 24 Pioneer Day Mo 30 Tisha B’av J 2020 31 Eid al-Adha (US Date) Mu AUGUST Physically Challenged Awareness Month 1 Lughnassadh W JANUARY 11 Krishna Janmashtami H 1 New Year’s Day F 15 Assumption of Blessed Virgin Mary RC Feast of the Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God RC Dormition of the Theotokos O 6 Epiphany P, RC 20 Al Hijra/Muharram Mu 7 Feast of the Nativity (Orthodox Christmas) O 13 Birth of Guru Gobind Singh S SEPTEMBER Hispanic/Latino Heritage Month 15 Maghi S 7 Labor Day F 19 Feast of the Epiphany O 19-20 Rosh Hashanah J 20 Martin Luther King, Jr. Birthday (Observed) F 22 Mabon / Autumn Equinox (Northern Hemisphere) W 28 Yom Kippur* J FEBRUARY Black/African American History Month 29 Ahura* Mu 1 Imbolc (Northern Hemisphere) W 5 Chinese New Year Bu Diversity Awareness Month + LGBTQ+ History Month 10 Tu Bishvat J OCTOBER 3-4 Sukkot J 14 St. Valentine’s Day RC, I 10 Shemini Atzeret* J 15 Nirvana Day / Parinirvana Day Bu, S 11 Simchat Torah* J 17 President’s Day F 17 Navaratri H 25 Shrove Tuesday P,RC 18 Birth of the B’ab Ba 26–29 Intercalary/Ayyam-i-ha * Ba 19 Birth of Baha’u’llah Ba 26 Ash Wednesday ` P,RC 20 Installation of Scriptures of Guru Granth Sahib S 22 Simchat Torah * J MARCH Women’s History Month 18 Mawlid al Nabi Mu 1-19 Nineteen Day Fast Period Ba 31 Halloween/All Hallows Eve I 2 Clean Monday (Lent Begins) O 9 Holika Dahan H NOVEMBER American Indian/Native American Heritage Month 10 Holi H 10-12 Holar Mohalla S 1 All Saints Day P, RC 17 St. -

Block Party Festival Planning and Ideas Toolkit

Block Party Festival Planning and Ideas Toolkit So you are going to host or join a block party… Congratulations! You don’t have to live on a block of single family homes to hold a block party; people in apartments and condos have them too! This tool kit offers tips and suggestions on how to make your party a smooth running success. You may decide to simply close your street to traffic and sip lemonade in the sun, or you may want to hold a parade, dance lessons and a fashion show…from the most simple to the most elaborate, it’s your call! Details you should discuss ahead of time: Setting the stage for success Planning ahead and getting others to share in the work are the keys to a successful party. ● Gather as many neighbours as possible and divide up the tasks: advertising, setup, helping out the elderly and/or disabled, coordinating food, security, dealing with vehicles, clean up, removal of barricades and furniture. Make a list of all the things that need to be done and have people sign on. ● Include everybody in the planning! Children, seniors, members of minority groups, people who speak different languages, people with disabilities, neighbourhood churches and so on. By far the best way to get people involved is to ask them directly. ● Decide on a possible theme for the block party. ● Think of an alternate plan in case of poor weather. You might want to track down some folding tents – perhaps from a local organisation or school – just in case you want to hold some activities under shelter. -

2019-2022 Calendar of Major Jewish Holidays

2019-2022 CALENDAR OF MAJOR JEWISH HOLIDAYS Please note: Jewish students may not be able to participate in school activities that take place on the days marked with an *. 2019 2020 2021 2022 PURIM Celebrates the defeat of the plot to destroy March 21 March 10 February 26 March 17 the Jews of Persia. PASSOVER Deliverance of the Jewish people from Egypt. The first *Eve. of April 19 *Eve. of April 8 *Eve. of March 27 *Eve of April 15 and last two days are observed as full holidays. There are *April 20 *April 9 *March 28 *April 16 dietary restrictions against leavened products (such as *April 21 *April 10 *March 29 *April17 bread, pastries, pasta, certain legumes and more) during *April 26 *April 15 *April 3 *April 21 all eight days of the holiday. *April 27 *April 16 *April 4 *April 22 SHAVUOT *Eve. of June 8 *Eve. of May 28 *Eve. of May 16 *Eve of June 3 Feast of Weeks, marks the giving of the Law (Torah) *June 9 *May 29 *May 17 *June 4 at Mt. Sinai. (Often linked with the Confirmation *June 10 *May 30 *May 18 *June 5 of teenagers.) ROSH HASHANAH *Eve. of Sept. 29 *Eve. of Sept. 18 *Eve. of Sept. 6 *Eve of Sept 25 The Jewish New Year; start of the Ten Days of Penitence. *Sept. 30 *Sept. 19 *Sept. 7 *Sept. 26 The first two days are observed as full holidays. *Oct. 1 *Sept. 20 *Sept. 8 *Sept. 27 YOM KIPPUR Day of Atonement; the most solemn day *Eve. -

Festival Handbook

This booklet was inspired by and written for participants in the Festival Encouragement Project (FEP), a program co-created in 2003 by the Center for Cultural Innovation and supported by a grant from the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs (LADCA). The goal of 2 the FEP is to build the strength and capacity of selected outdoor cultural celebrations produced in L.A. that serve residents and tourists. Book Photography: Aaron Paley Book Design: Peter Walberg Published by the Center for Cultural Innovation TABLE OF CONTENTS Artists shown on the following pages: INTRODUCTION Judith Luther Wilder Cover Dragonfly by Lili Noden’s Dragon Knights ONE Festivals: Their Meaning and Impact in the City of Angels Page 2 Titus Levi, PhD. Jason Samuels Smith, Anybody Can Get It TWO Page 4 A Brief Historical Overview of Selected Festivals in Los Angeles- 1890-2005 Nathan Stein Aaron Paley Page 6 THREE Tracy Lee Stum Madonnara, Street painter Why? An Introduction to Producing a Festival Hope Tschopik Schneider Page 7 Saaris African Foods FOUR Santa Monica Festival 2002 Choosing Place: What Makes a Good Festival Site? Page 9 Maya Gingery Procession, streamers by Celebration Arts Holiday Stroll in Palisades Park, FIVE Santa Monica Timelines & Workplans Page 11 Aaron Paley Body Tjak, created by I Wayan Dibia and Keith Terry SIX Santa Monica Festival 2002 The Business Side of Festivals Sumi Sevilla Haru Page 12 Ricardo Lemvo and Makina Loca on stage at POW WOW SEVEN Grand Avenue Party 2004 Public Relations Advice for Festival Producers -

2021 AV Fair and Alfalfa Festival “Barntoberfest” General Information

2021 AV Fair and Alfalfa Festival “Barntoberfest” General Information 2021 AV Fair & Alfalfa Festival ‘Barntoberfest”: October 1st – 10th. Closed on Monday 10/4 and Tuesday 10/5. There’s nothing like Fair Fun! Tickets for the annual AV Fair are on sale. This year there is limited daily attendance, and days could sell out. Be sure to plan and purchase your online tickets early. As we prepare for our 2021 Annual AV Fair & Alfalfa Festival, the health and safety of our community, and you remain a top priority. We have and will continue taking steps that ensure all of our Fair guests have a fun, memorable and stress-free time at this year’s Fair. Be sure to familiarize yourself with our new protocols as we make attending this year’s Fair simple, easy & safe. Currently Tickets must be purchased online and in advance at avfair.com. Fairgoers - make sure to get tickets for special days and group adventures now. Are you ready to Fair? Key things to know: • Currently advance purchase of tickets is required • Currently ticket purchasing will not be available at the gate. This may change – be sure to check back for updates! • Tickets are good only for the date purchased; please choose dates carefully • No admission ticket refunds • Masks are required for all guests regardless of vaccination status inside all Fair buildings. If you have additional questions, please click here for our 2021 FAQ’s. AV Fair Dates & Hours: • October 1-10th – Closed on Monday 10/4 and Tuesday 10/5 • Open 4pm – midnight on weekdays • Open 12noon – midnight Saturday’s & Sunday’s Single-Day Admission Pricing: Currently admission tickets, parking and arena tickets must be purchased online, in advance, and will not be available for purchase at the gate.