West Bank Unrwa Profile: Tulkarm Camp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

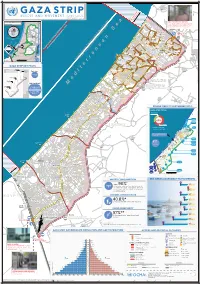

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87598-1 - The War for Palestine: Rewriting the History of 1948, Second Edition Edited by Eugene L. Rogan and Avi Shlaim Excerpt More information Introduction The Palestine War lasted less than twenty months, from the United Nations resolution recommending the partition of Palestine in November 1947 to the final armistice agreement signed between Israel and Syria in July 1949. Those twenty months transformed the political landscape of the Middle East forever. Indeed, 1948 may be taken as a defining moment for the region as a whole. Arab Palestine was destroyed and the new state of Israel established. Egypt, Syria and Lebanon suffered outright defeat, Iraq held its lines, and Transjordan won at best a pyrrhic victory. Arab public opinion, unprepared for defeat, let alone a defeat of this magnitude, lost faith in its politicians. Within three years of the end of the Palestine War, the prime ministers of Egypt and Lebanon and the king of Jordan had been assassinated, and the president of Syria and the king of Egypt over- thrown by military coups. No event has marked Arab politics in the second half of the twentieth century more profoundly. The Arab–Israeli wars, the Cold War in the Middle East, the rise of the Palestinian armed struggle, and the politics of peace-making in all of their complexity are a direct con- sequence of the Palestine War. The significance of the Palestine War also lies in the fact that it was the first challenge to face the newly independent states of the Middle East. -

National Report, State of Palestine United Nations

National Report, State of Palestine United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (Habitat III) 2014 Ministry of Public Works and Housing National Report, State of Palestine, UN-Habitat 1 Photo: Jersualem, Old City Photo for Jerusalem, old city Table of Contents FORWARD 5 I. INTRODUCTION 7 II. URBAN AGENDA SECTORS 12 1. Urban Demographic 12 1.1 Current Status 12 1.2 Achievements 18 1.3 Challenges 20 1.4 Future Priorities 21 2. Land and Urban Planning 22 2. 1 Current Status 22 2.2 Achievements 22 2.3 Challenges 26 2.4 Future Priorities 28 3. Environment and Urbanization 28 3. 1 Current Status 28 3.2 Achievements 30 3.3 Challenges 31 3.4 Future Priorities 32 4. Urban Governance and Legislation 33 4. 1 Current Status 33 4.2 Achievements 34 4.3 Challenges 35 4.4 Future Priorities 36 5. Urban Economy 36 5. 1 Current Status 36 5.2 Achievements 38 5.3 Challenges 38 5.4 Future Priorities 39 6. Housing and Basic Services 40 6. 1 Current Status 40 6.2 Achievements 43 6.3 Challenges 46 6.4 Future Priorities 49 III. MAIN INDICATORS 51 Refrences 52 Committee Members 54 2 Lists of Figures Figure 1: Percent of Palestinian Population by Locality Type in Palestine 12 Figure 2: Palestinian Population by Governorate in the Gaza Strip (1997, 2007, 2014) 13 Figure 3: Palestinian Population by Governorate in the West Bank (1997, 2007, 2014) 13 Figure 4: Palestinian Population Density of Built-up Area (Person Per km²), 2007 15 Figure 5: Percent of Change in Palestinian Population by Locality Type West Bank (1997, 2014) 15 Figure 6: Population Distribution -

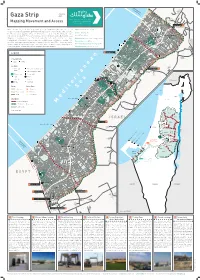

Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary

Zikim Karmiya No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles Yad Mordekhai January Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary Ar-Rasheed Wastewater Treatment Lagoons Sources: OCHA, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics of Statistics Bureau Central OCHA, Palestinian Sources: Erez Crossing 1 Al-Qarya Beit Hanoun Al-Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) Erez What is known today as the Gaza Strip, originally a region in Mandatory Palestine, was created Width 5.7-12.5 km / 3.5 – 7.7 mi through the armistice agreements between Israel and Egypt in 1949. From that time until 1967, North Gaza Length ~40 km / 24.8 mi Al- Karama As-Sekka the Strip was under Egyptian control, cut off from Israel as well as the West Bank, which was Izbat Beit Hanoun al-Jaker Road Area 365 km2 / 141 m2 Beit Hanoun under Jordanian rule. In 1967, the connection was renewed when both the West Bank and the Gaza Madinat Beit Lahia Al-'Awda Strip were occupied by Israel. The 1993 Oslo Accords define Gaza and the West Bank as a single Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Population 1,943,398 • 48% Under age 17 July 2019 Industrial Zone Ash-Shati Housing Project Jabalia Sderot territorial unit within which freedom of movement would be permitted. However, starting in the camp al-Wazeer Unemployment rate 47% 2019 Q2 Jabalia Camp Khalil early 90s, Israel began a gradual process of closing off the Strip; since 2007, it has enforced a full Ash-Sheikh closure, forbidding exit and entry except in rare cases. Israel continues to control many aspects of Percentage of population receiving aid 80% An-Naser Radwan Salah Ad-Deen 2 life in Gaza, most of its land crossings, its territorial waters and airspace. -

1948 Arab‒Israeli

1948 Arab–Israeli War 1 1948 Arab–Israeli War מלחמת or מלחמת העצמאות :The 1948 Arab–Israeli War, known to Israelis as the War of Independence (Hebrew ,מלחמת השחרור :, Milkhemet Ha'atzma'ut or Milkhemet HA'sikhror) or War of Liberation (Hebrewהשחרור Milkhemet Hashikhrur) – was the first in a series of wars fought between the State of Israel and its Arab neighbours in the continuing Arab-Israeli conflict. The war commenced upon the termination of the British Mandate of Palestine and the Israeli declaration of independence on 15 May 1948, following a period of civil war in 1947–1948. The fighting took place mostly on the former territory of the British Mandate and for a short time also in the Sinai Peninsula and southern Lebanon.[1] ., al-Nakba) occurred amidst this warﺍﻟﻨﻜﺒﺔ :Much of what Arabs refer to as The Catastrophe (Arabic The war concluded with the 1949 Armistice Agreements. Background Following World War II, on May 14, 1948, the British Mandate of Palestine came to an end. The surrounding Arab nations were also emerging from colonial rule. Transjordan, under the Hashemite ruler Abdullah I, gained independence from Britain in 1946 and was called Jordan, but it remained under heavy British influence. Egypt, while nominally independent, signed the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 that included provisions by which Britain would maintain a garrison of troops on the Suez Canal. From 1945 on, Egypt attempted to renegotiate the terms of this treaty, which was viewed as a humiliating vestige of colonialism. Lebanon became an independent state in 1943, but French troops would not withdraw until 1946, the same year that Syria won its independence from France. -

Chapter 5. Development Frameworks

Chapter 5 JERICHO Regional Development Study Development Frameworks CHAPTER 5. DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORKS 5.1 Socioeconomic Framework Socioeconomic frameworks for the Jericho regional development plan are first discussed in terms of population, employment, and then gross domestic product (GDP) in the region. 5.1.1 Population and Employment The population of the West Bank and Gaza totals 3.76 million in 2005, according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) estimation.1 Of this total, the West Bank has 2.37 million residents (see the table below). Population growth of the West Bank and Gaza between 1997 and 2005 was 3.3%, while that of the West Bank was slightly lower. In the Jordan Rift Valley area, including refugee camps, there are 88,912 residents; 42,268 in the Jericho governorate and 46,644 in the Tubas district2. Population growth in the Jordan Rift Valley area is 3.7%, which is higher than that of the West Bank and Gaza. Table 5.1.1 Population Trends (1997-2005) (Unit: number) Locality 1997 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 CAGR West Bank and Gaza 2,895,683 3,275,389 3,394,046 3,514,868 3,637,529 3,762,005 3.3% West Bank 1,873,476 2,087,259 2,157,674 2,228,759 2,300,293 2,372,216 3.0% Jericho governorate 31,412 37,066 38,968 40,894 40,909 42,268 3.8% Tubas District 35,176 41,067 43,110 45,187 45,168 46,644 3.6% Study Area 66,588 78,133 82,078 86,081 86,077 88,912 3.7% Study Area (Excl. -

REFUGEE CAMPS in the West Bank We Provide Services in 19 Palestine Refugee Camps in the West Bank

PALESTINIAN REFUGEES IN WEST BANK & GAZA STRIP https://www.unrwa.org/palestine-refugees Nearly one-third of the registered Palestine refugees, more than 1.5 million individuals, live in 58 recognized Palestine refugee camps in Jordan, Lebanon, the Syrian Arab Republic, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem. Palestine refugees are defined as “persons whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948, and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict.” UNRWA services are available to all those living in its area of operations who meet this definition, who are registered with the Agency and who need assistance. The descendants of Palestine refugee males, including adopted children, are also eligible for registration. When the Agency began operations in 1950, it was responding to the needs of about 750,000 Palestine refugees. Today, some 5 million Palestine refugees are eligible for UNRWA services. A Palestine refugee camp is defined as a plot of land placed at the disposal of UNRWA by the host government to accommodate Palestine refugees and set up facilities to cater to their needs. Areas not designated as such and are not recognized as camps. However, UNRWA also maintains schools, health centres and distribution centres in areas outside the recognized camps where Palestine refugees are concentrated, such as Yarmouk, near Damascus. WEST BANK: (31 dec 2016) https://www.unrwa.org/where-we-work/west-bank Facts & figures : 809,738 registered Palestine refugees 19 camps 96 schools, with 48,956 pupils 2 vocational and technical training centres 43 primary health centres 15 community rehabilitation centres 19 women’s programme centres REFUGEE CAMPS IN the West Bank We provide services in 19 Palestine refugee camps in the West Bank. -

Summary of Consultation on Effects of the COVID-19 on Women in Palestine

Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics A Summary of Statistical Indicators on Women in Palestine during the Covid19 Crises Most Vulnerable Women Segments Around 10,745 women Health care health system workers and a total of 31,873 workers men and women 900 women working in workers in Palestine Women working in Israel Israel and settlements and settelements mostly in agriculture 175891 total females with chronic Women with Chronic disease 69,112 women suffer from at least one Chronic Disease (60+) Disease The percentage of poverty Female Childen with disease 9,596 female among households headed children with chronic by women in 2017 was 19% in the WB and 54% in Poor women Gaza Strip Elderly women In 2020 there are 140 287 60+ women 92,584 women heading households (61241 WB, Women Heading households 31343 Gaza Strip – 41,017 of highest in Jericho women have Women with disabilities at least one type of disability 1 Social Characteristics 1. The elderly (the most vulnerable group) • The number of elderly people (60+ years) in the middle of 2020 is around 269,346, (5.3% women, 140,287, and 129,059 men) • The percentage of elderly in Palestine was 5.0% of the total population in 2017 (5.4% for the elderly females, 4.6% for the elderly males), and in the West Bank it is higher than in the Gaza Strip (5.4 % In the West Bank and 4.3% in the Gaza Strip). • At the governorate level, the highest percentage of elderly people was in the governorates of Tulkarm, Ramallah, Al-Bireh, Bethlehem, and Jerusalem (6.5%, 6.0%, 6.0%, and 5.9%, respectively). -

Protection of Civilians – Weekly Briefing Notes 26 April – 2 May 2006

U N I TOCHA E D Weekly N A Briefing T I O NotesN S 26 April – 2 May 2006 N A T I O N S| 1 U N I E S OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS P.O. Box 38712, East Jerusalem, Phone: (+972) 2-582 9962 / 582 5853, Fax: (+972) 2-582 5841 [email protected], www.ochaopt.org Protection of Civilians – Weekly Briefing Notes 26 April – 2 May 2006 Of note this period • Comprehensive external closure continued for the seventh consecutive week (since 11 March) with no movement of Palestinian workers and traders in Israel. The IDF announced on 1 May that the closure would also include national staff of international organisations. • Internal movement within the West Bank and into the Jordan Valley remained very restricted. Restrictions for Palestinians from the northern West Bank to move south of Nablus governorate continue to remain in place. Movement through Tayasir and Hamra checkpoints (Tubas) remain restricted. Humanitarian organisations and ambulances are facing major access problems at ‘Asira ash Shamaliya checkpoint in Nablus. 1. Physical Protection 30 20 10 0 Children Women Injuries Deaths Deaths Deaths Palestinians 25 2 - 1 Israelis 1--- Internationals ---- • During the week the IDF fired more than 90 artillery tank shells, particularly into the northern areas and east of Gaza City (Gaza Strip) resulting in Palestinian injuries. The IAF also conducted one air strike (targeted killing) in the Gaza Strip killing one Palestinian man and injuring another. • At least 23 home made (Qassam) rockets were fired by Palestinian militants from the Gaza Strip toward targets inside Israel. -

Protection of Civilians Weekly Report

U N I T E D OCHA N A WeeklyT I O NRepor S t: 31 January – 6 February 2007 N A T I O N S U N| 1 I E S OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS P.O. Box 38712, East Jerusalem, Phone: (+972) 2-582 9962 / 582 5853, Fax: (+972) 2-582 5841 [email protected], www.ochaopt.org P r o t e c t i o n o f C i v i l i a n s W e e k l y R e p o r t 31 January – 6 February 2007 Of note this week Gaza Strip: A number of incidents occurred between Israeli forces and Palestinians in the Gaza Strip, but the ceasefire held. Internal violence: − Inter-factional fighting continued in the Gaza Strip. According to MoH sources, 34 Palestinians died, including two women and four children, and 251 were injured.1 − Five Palestinians, including a woman bystander, were killed and 24 others injured when Hamas ESF ambushed trucks carrying containers that belonged to the Presidential Guard. − The Presidential Guard broke into the Islamic University and clashed with the Hamas ESF. Significant damages to the university’s buildings including the main library were reported. − Schooling in the Gaza Strip was severely disturbed, more significantly in Gaza City and northern Gaza. − Checkpoints and presence of snipers severely affected civilian life in the Gaza Strip. West Bank: − Six Palestinians were killed and 16 injured in the West Bank. One IDF soldier was injured. − 131 ‘flying’ or random checkpoints set up by the IDF were observed; 135 search and arrest operations were conducted by the IDF resulting in 145 arrests predominately in Hebron, Jenin and Nablus governorates. -

Protection of Civilians – Weekly Briefing Notes 3 – 9 May 2006

U N I TOCHA E D Weekly N A Briefing T I O NotesN S 3 – 9 May 2006 N A T I O N S| 1 U N I E S OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS P.O. Box 38712, East Jerusalem, Phone: (+972) 2-582 9962 / 582 5853, Fax: (+972) 2-582 5841 [email protected], www.ochaopt.org Protection of Civilians – Weekly Briefing Notes 3 – 9 May 2006 Of note this period • The comprehensive external closure, in place since 11 March, was lifted in the West Bank on 8 May. The closure continues however on the Gaza Strip. • Gaza militants fired 29 home made rockets towards Israel and IDF shelling continued to target areas in the Gaza Strip; this week more than 300 shells were fired. 1. Physical Protection1 30 20 10 0 Children Women Injuries Deaths Deaths Deaths Palestinians 24 9 - - Israelis 3--- Internationals 3--- • At least 29 home made (Qassam) rockets were fired by Palestinian militants from the Gaza Strip toward targets inside Israel. • During the week the IDF fired more than 300 artillery tank shells, particularly into the northern areas and east of Gaza City (Gaza Strip). The IAF also conducted three air strikes in the Gaza Strip. • 3 May: A three-year-old Palestinian boy from H2 area of Hebron city (Hebron) was injured after being run over by an Israeli settler from Kiryat Arba settlement. (Not counted in the weekly casualty total). • 3 May: The IDF injured a 22-year-old handicapped Palestinian man from Beit Awwa (Hebron). • 3 May: A 37-years-old Palestinian taxi driver from Tubas was killed by the IDF after crossing an earth mound on Al Badhan road on foot (Nablus). -

Protection of Civilians - Weekly Briefing Notes 30 November – 6 December 2005

U N I TOCHA E D Weekly N A Briefing T I O NotesN S 30 November – 6 December 2005 N A T I O N S| 1 U N I E S OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS P.O. Box 38712, East Jerusalem, Phone: (+972) 2-582 9962 / 582 5853, Fax: (+972) 2-582 5841 [email protected], www.ochaopt.org Protection of Civilians - Weekly Briefing Notes 30 November – 6 December 2005 Of note this week • A Palestinian suicide bomber killed five and injured more than 50 Israelis at the entrance of a shopping mall in Netanya. A general closure was imposed on the oPt on 6 December. Barrier construction has started around Ma’ale Adumim settlement. 1. Physical Protection 1 Casualties 80 60 40 20 0 Children Women Injuries Deaths Deaths Deaths Palestinians 22 4 1 0 Israelis 60 5 0 2 Internationals 0000 • 30 November: One Palestinian minor aged 12 years old was injured in Jenin camp (Jenin) during and IDF search in the family’s house. • 30 November: Palestinians threw stones at the IDF who surrounded a house in Nablus city (Nablus). The IDF fired tear gas canisters and rubber coated metal bullets, injuring eight Palestinians. • 1 December: The IDF shot and injured one 23-year-old Palestinian during clashes with stone throwing Palestinians in Balata refugee camp (Nablus). • 2 December: Five Palestinians and one Israeli activist were injured by the IDF during a demonstration organized by Palestinians, international and Israeli activists against Barrier construction in Bil’in (Ramallah). • 2 December: Palestinians, international and Israeli activists demonstrated against the construction of the “special security arrangements” around Ofarim and Beit Arye settlements (Ramallah).