Everything You Wanted to Know About Subwoofers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second Bassoon: Specialist, Support, Teamwork Dick Hanemaayer Amsterdam, Holland (!E Following Article first Appeared in the Dutch Magazine “De Fagot”

THE DOUBLE REED 103 Second Bassoon: Specialist, Support, Teamwork Dick Hanemaayer Amsterdam, Holland (!e following article first appeared in the Dutch magazine “De Fagot”. It is reprinted here with permission in an English translation by James Aylward. Ed.) t used to be that orchestras, when they appointed a new second bassoon, would not take the best player, but a lesser one on instruction from the !rst bassoonist: the prima donna. "e !rst bassoonist would then blame the second for everything that went wrong. It was also not uncommon that the !rst bassoonist, when Ihe made a mistake, to shake an accusatory !nger at his colleague in clear view of the conductor. Nowadays it is clear that the second bassoon is not someone who is not good enough to play !rst, but a specialist in his own right. Jos de Lange and Ronald Karten, respectively second and !rst bassoonist from the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra explain.) BASS VOICE Jos de Lange: What makes the second bassoon more interesting over the other woodwinds is that the bassoon is the bass. In the orchestra there are usually four voices: soprano, alto, tenor and bass. All the high winds are either soprano or alto, almost never tenor. !e "rst bassoon is o#en the tenor or the alto, and the second is the bass. !e bassoons are the tenor and bass of the woodwinds. !e second bassoon is the only bass and performs an important and rewarding function. One of the tasks of the second bassoon is to control the pitch, in other words to decide how high a chord is to be played. -

Frequently Asked Questions About Sound Blaster X7 Ver

Frequently Asked Questions about the Sound Blaster X7 General 1. Why is the Sound Blaster X7 so light? The Sound Blaster X7 was designed with an external power adapter, as opposed to regular amplifiers with internal transformers, which greatly takes away the bulk and weight from the product itself. The combined weight of the Sound Blaster X7 unit together with the power adapter is approximately 1.1 kg. The Sound Blaster X7 was engineered and designed for power efficiency, heat management and component synergy, resulting in reduced overall weight. We also wanted to create a product with a small footprint that can easily placed next to a desktop computer or in a living room home audio setup. 2. How is heat being managed on the Sound Blaster X7? The Sound Blaster X7 uses an efficient power amplifier that only requires a small heat sink for heat dissipation. The Sound Blaster X7 also complies with ErP, the latest European Union Directive for energy management. 3. Do I need to upgrade to the 24V, 6A high power adapter? The Sound Blaster X7 comes bundled with a 24V, 2.91A power adapter, which should give you 20+20W – 27+27W (into 8 ohms speakers) and 35+35W – 38+38W (into 4 ohms speakers) in normal usage scenarios. Such output power is sufficient in an average room setup. You will only need an upgrade to the higher power adapter if you require more audio power. Connectivity to Audio/Video (AV) Systems 1. I currently have an AV system at home. How do I connect the Sound Blaster X7 to it? You can connect the Sound Blaster X7 to your home AV system via TOSLINK*. -

Laker Drumline Marching Bass Drum Technique

Laker Drumline Marching Bass Drum Technique This packet is intended to define a base framework of knowledge to adequately play a marching bass drum at the collegiate level. We understand that every high school drumline has its own approach to technique, so it’s crucial that ALL prospective members approach their hands with a fresh mind and a clean slate. Mastery of the following concepts & terminology will dramatically improve your experience during the audition process and beyond. Happy drumming! APPROACH The technique outlined in this packet is designed to maximize efficiency of motion and sound quality. It is necessary to use a high velocity stroke while keeping your grip and your muscles relaxed. Keep these key points in mind as you work to refine the music in this packet. Tension in your upper body, lack of oxygen to your muscles, and squeezing the stick are good examples of technique errors that will hinder your ability to achieve the sound quality, efficiency, and control that we strive for. GRIP Fulcrum Place the mallet perpendicularly across the second segment of your index finger. Place your thumb on the mallet so that the thumbnail is directly across from your index finger. ** This is the essential point of contact between your hands and the stick. It should be thought of as the primary pressure point in your fingers and pivot point on the stick. The entire pad of your thumb should remain in contact with the mallet at all times. As a bass drummer, about 60% of the pressure in your hands should lie in the fulcrum. -

10 - Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1

Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. The Keyboard and Treble Clef Chapter 2. Bass Clef In this chapter you will: 1.Write bass clefs 2. Write some low notes 3. Match low notes on the keyboard with notes on the staff 4. Write eighth notes 5. Identify notes on ledger lines 6. Identify sharps and flats on the keyboard 7.Write sharps and flats on the staff 8. Write enharmonic equivalents date: 2.1 Write bass clefs • The symbol at the beginning of the above staff, , is an F or bass clef. • The F or bass clef says that the fourth line of the staff is the F below the piano’s middle C. This clef is used to write low notes. DRAW five bass clefs. After each clef, which itself includes two dots, put another dot on the F line. © Gilbert DeBenedetti - 10 - www.gmajormusictheory.org Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. The Keyboard and Treble Clef 2.2 Write some low notes •The notes on the spaces of a staff with bass clef starting from the bottom space are: A, C, E and G as in All Cows Eat Grass. •The notes on the lines of a staff with bass clef starting from the bottom line are: G, B, D, F and A as in Good Boys Do Fine Always. 1. IDENTIFY the notes in the song “This Old Man.” PLAY it. 2. WRITE the notes and bass clefs for the song, “Go Tell Aunt Rhodie” Q = quarter note H = half note W = whole note © Gilbert DeBenedetti - 11 - www.gmajormusictheory.org Pathways to Harmony, Chapter 1. -

General Product Answers

FAQ GENERAL PRODUCT ANSWERS What types of loudspeaker are there (active, passive, DSP, etc.) and what technologies are used in them? The following basic types of loudspeaker design are commonly manufactured (Neumann does not make all of these types): GENERAL PRODUCT ANSWERS | 1 GENERAL PRODUCT ANSWERS | 2 GENERAL PRODUCT ANSWERS | 3 The following technologies are commonly seen in the different types of loudspeaker designs on the market (Neumann does not use all of these technologies. Also included are some less common techniques): Inputs ▪ Analog: electronic-balanced, transformer-balanced, loudspeaker level: low impedance, high impedance (70 V, 100 V) ▪ Digital: S/P-DIF, AES3, Firewire, USB, audio network Converters ▪ D-A: typically Oversampling or Interpolating used ▪ A-D: typically Sigma-Delta used ▪ SRC added if fixed-rate processing follows Crossover/Processing ▪ Passive: 1st, 2nd, 3rd order ▪ Active: 2nd, 3rd , 4th order ▪ DSP: IIR with 4th, 6th, 8th order, FIR with any order up to 16, linear phase, non-linear compensation Amplifiers ▪ Class A, B, AB, C, D, H Power Supplies ▪ Fixed linear (transformer), switchable linear (transformer), universal (switched-mode) Protection ▪ Passive: multifuse, soffite, relay + network, fuse, bimetal ▪ Active: inputs, amplifiers (thermal, short-circuit), drivers thermal limiting, excursion limiting ▪ DSP: look ahead limiters, power supply monitoring Drivers ▪ High frequency (tweeter, top): soft dome, hard dome (aluminum, titanium, ceramic, diamond), ribbon, folded ribbon, compression, plasma. ▪ Midrange -

Bar 2.1 Deep Bass

BAR 2.1 DEEP BASS OWNER’S MANUAL JBL_SB_Bar 2.1_OM_V3.indd 1 7/4/2019 3:26:40 PM IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS Verify Line Voltage Before Use The JBL Bar 2.1 Deep Bass (soundbar and subwoofer) has been designed for use with 100-240 volt, 50/60 Hz AC current. Connection to a line voltage other than that for which your product is intended can create a safety and fire hazard and may damage the unit. If you have any questions about the voltage requirements for your specific model or about the line voltage in your area, contact your retailer or customer service representative before plugging the unit into a wall outlet. Do Not Use Extension Cords To avoid safety hazards, use only the power cord supplied with your unit. We do not recommend that extension cords be used with this product. As with all electrical devices, do not run power cords under rugs or carpets, or place heavy objects on them. Damaged power cords should be replaced immediately by an authorized service center with a cord that meets factory specifications. Handle the AC Power Cord Gently When disconnecting the power cord from an AC outlet, always pull the plug; never pull the cord. If you do not intend to use this speaker for any considerable length of time, disconnect the plug from the AC outlet. Do Not Open the Cabinet There are no user-serviceable components inside this product. Opening the cabinet may present a shock hazard, and any modification to the product will void your warranty. -

This Catalogue Presents the Best and Most Comprehensive Range Of

This catalogue presents the best and most comprehensive range of products, aesthetic features and solutions for sound, intercommunication and public address system installations, backed by EGi’s guarantee of more than 30 years of experience in the market. EGi has a Customer Service and Technical- Commercial Assistance Service which gives assessment, advice and carry out projects helping you to choose the best solution for each installation. 1-EGi corporativaINSTALACIONES-ING.indd 1 4/2/09 16:50:45 With headquarters in Spain and 5 branch offices nationwide including Madrid and Barcelona, EGi is continuously strengthening its international presence with branches in Portugal and Singapore EGi began as a small family business in Zaragoza and was founded by its current chairman, Mr Sánchez Pérez EGi has been awarded ISO 9001:2000 certification for its commitment to quality, Pilot Award for Logistics Excellence 2004, and Best Telecommunications Company in the self-governing region of Aragon, Spain EGi participates in national and international exhibitions 2 1-EGi corporativaINSTALACIONES-ING.indd 2 4/2/09 16:50:51 EGi headquarters are strategically located in Zaragoza with direct access to the road network and cover an area of about 5.300 m2, housing more than 150 employees New factory and warehouse building for the lighting division. This new building with an area of 5.000 m2 is located in Centrovia, one of the largest industrial parks in Zaragoza Over 30 years of experience providing new audio technology 3 1-EGi corporativaINSTALACIONES-ING.indd -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands. -

Single Product Page

Wireless Portable Karaoke Speaker with Disco Dome Light NDS-1208 Features Specifications Drivers: 1.5'' tweeter + 12'' subwoofer Number of Speakers: 1 tweeter + 1 subwoofer Domed Multicolor LED disco room light + Woofer with Disco Light and Dual Side Input Sources: Karaoke 6.3 mm MIC, 3.5 mm AUX Bar Flashing Lights Tuners: FM Peak Music Power Output (PMPO): 3,000W Inputs: Karaoke 6.3 mm MIC, 3.5 mm AUX Audio Format Support: MP3 5 Control Levels including Master Volume, Treble, Bass, Echo, MIC Vol. Removable Memory Support: USB / Micro SD Card Stream music wirelessly from Bluetooth® devices Wireless Source: Bluetooth® Built-in MP3 player supports USB and MicroSD memory cards Peak Music Power Output (PMPO): 3000 W FM radio tuner LED display Subwoofer weight: 100 oz. Easy-to-use telescoping handle and trolley wheels Subwoofer driver size: 12.0 in Power: Built-in Rechargeable battery (12V, 4.5A), AC power adapter Speaker Driver Size: 1.5 in Accessories included: 1 pc. Corded microphone, remote control, AC power adapter, AUX cable Light effects: Woofer with Disco Light, Top Dome and 2x side Flashing Lights Level controls: Master Volume, Treble, Bass, Echo, MIC Power Source: AC power cord with rechargeable battery Product Details Power Adapter 1 In: 100 - 240VAC, 50/60 Hz Battery Type: Built-in rechargeable Li-ion Model Battery capacity: 4500 mAh (3 hrs. at Max Vol.) NDS-1208 Unit Battery, voltage: 12V - 4.5A Dimensions (in): 15 x 11.91 x 27.5 [ L x W x H ] Accessories included: 1pc. Wired Mic, Remote Control, AC power cord, Weight (lbs): 26 Warranty Card, User's Manual Giftbox/Clamshell Dimensions (in): 17 x 13.8 x 29 [ L x W x H ] Weight (lbs): 30.93 Master Carton # Of Units/per: 1 Dimensions (in): 17 X 13.8 X 29 [ L x W x H ] Weight (lbs): 30.93 Loading Qty/Container 20: 232 40: 502 40HQ: 610 PRODUCT URL:https://naxa.com/product/wireless-portable-karaoke-speaker-with-disco-dome-light-3/ Features, specifications, measurements and weights may be subject to change without prior notice.. -

Extended Performance. Ultra-Compact Subwoofer

Extended Performance. Ultra-Compact Subwoofer. Genelec 7040 Active subwoofer Common issues, Genelec solution The 7040 is an ultra-compact subwoofer solution designed around Genelec proven Laminar Spiral Enclosure (LSE™) technology, enabling accurate sound reproduction and precise monitoring of low frequency content. The Genelec 7040 active subwoofer has been developed to complement Genelec 8010, 8020 and M030 active monitors. Such a monitoring system enables work at a professional quality level in typical small rooms, or not purpose-built monitoring environments, for music creation and sound design, as well as audio and video productions. Low frequency accuracy Portable flexibility To achieve a high sound pressure level The design goal for the 7040 subwoofer was to an essential property of a subwoofer is its develop a tool for professional, reliable, quality capacity to move high volumes of air without low frequency reproduction in a transportable distortion. This presents challenges to woofer package. and reflex port designs. The solution is The 7040 subwoofer weighs a mere Genelec’s patented Laminar Spiral Enclosure 11.3 kg (25 lb) and features a universal (LSE™). It is a result of more than 10 years mains input voltage for easy international of continuous research of research work and connectivity. The two balanced XLR inputs manufacturing experience. and bass managed outputs, via an 85 Hz The 7040 active subwoofer can produce crossover, enable seamless extension with the 100 dB of sound pressure level (SPL) using main monitors. Calibration of the Genelec 7040 a 6 ½ inch woofer and a powerful Genelec- subwoofer to the listening environment is done designed Class D amplifier. -

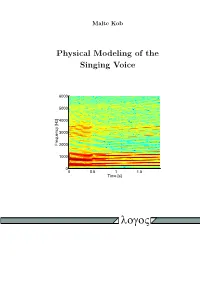

Physical Modeling of the Singing Voice

Malte Kob Physical Modeling of the Singing Voice 6000 5000 4000 3000 Frequency [Hz] 2000 1000 0 0 0.5 1 1.5 Time [s] logoV PHYSICAL MODELING OF THE SINGING VOICE Von der FakulÄat furÄ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik der Rheinisch-WestfÄalischen Technischen Hochschule Aachen zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines DOKTORS DER INGENIEURWISSENSCHAFTEN genehmigte Dissertation vorgelegt von Diplom-Ingenieur Malte Kob aus Hamburg Berichter: UniversitÄatsprofessor Dr. rer. nat. Michael VorlÄander UniversitÄatsprofessor Dr.-Ing. Peter Vary Professor Dr.-Ing. JuÄrgen Meyer Tag der muÄndlichen PruÄfung: 18. Juni 2002 Diese Dissertation ist auf den Internetseiten der Hochschulbibliothek online verfuÄgbar. Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Kob, Malte: Physical modeling of the singing voice / vorgelegt von Malte Kob. - Berlin : Logos-Verl., 2002 Zugl.: Aachen, Techn. Hochsch., Diss., 2002 ISBN 3-89722-997-8 c Copyright Logos Verlag Berlin 2002 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. ISBN 3-89722-997-8 Logos Verlag Berlin Comeniushof, Gubener Str. 47, 10243 Berlin Tel.: +49 030 42 85 10 90 Fax: +49 030 42 85 10 92 INTERNET: http://www.logos-verlag.de ii Meinen Eltern. iii Contents Abstract { Zusammenfassung vii Introduction 1 1 The singer 3 1.1 Voice signal . 4 1.1.1 Harmonic structure . 5 1.1.2 Pitch and amplitude . 6 1.1.3 Harmonics and noise . 7 1.1.4 Choir sound . 8 1.2 Singing styles . 9 1.2.1 Registers . 9 1.2.2 Overtone singing . 10 1.3 Discussion . 11 2 Vocal folds 13 2.1 Biomechanics . 13 2.2 Vocal fold models . 16 2.2.1 Two-mass models . 17 2.2.2 Other models . -

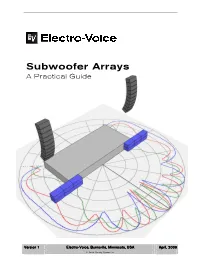

Subwoofer Arrays: a Practical Guide

Subwoofer Arrays A Practical Guide VVVeVeeerrrrssssiiiioooonnnn 111 EEElEllleeeeccccttttrrrroooo----VVVVooooiiiicccceeee,,,, BBBuBuuurrrrnnnnssssvvvviiiilllllleeee,,,, MMMiMiiinnnnnneeeessssoooottttaaaa,,,, UUUSUSSSAAAA AAApAppprrrriiiillll,,,, 22202000009999 © Bosch Security Systems Inc. Subwoofer Arrays A Practical Guide Jeff Berryman Rev. 1 / June 7, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................1 2. Acoustical Concepts.......................................................................................................................................2 2.1. Wavelength ..........................................................................................................................................2 2.2. Basic Directivity Rule .........................................................................................................................2 2.3. Horizontal-Vertical Independence...................................................................................................3 2.4. Multiple Sources and Lobing ...........................................................................................................3 2.5. Beamforming........................................................................................................................................5 3. Gain Shading....................................................................................................................................................6