“Gotta Catch 'Em All!” Pokémon, Cultural Practice and Object

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pokemon Buy List

Pokemon Buy List Card Name Set Rarity Cash Value Credit Value Absol EX - XY62 XY Promos Holofoil $1.04 $1.24 Acerola (Full Art) SM - Burning Shadows Holofoil $6.16 $7.39 Acro Bike (Secret) SM - Celestial Storm Holofoil $5.11 $6.13 Adventure Bag (Secret) SM - Lost Thunder Holofoil $2.72 $3.26 Aegislash EX XY - Phantom Forces Holofoil $1.06 $1.27 Aegislash V SWSH04: Vivid Voltage Holofoil $0.68 $0.82 Aegislash V (Full Art) SWSH04: Vivid Voltage Holofoil $3.96 $4.75 Aegislash VMAX SWSH04: Vivid Voltage Holofoil $1.07 $1.28 Aegislash VMAX (Secret) SWSH04: Vivid Voltage Holofoil $6.28 $7.54 Aerodactyl EX - XY97 XY Promos Holofoil $0.84 $1.00 Aerodactyl GX SM - Unified Minds Holofoil $0.88 $1.05 Aerodactyl GX (Full Art) SM - Unified Minds Holofoil $1.56 $1.87 Aerodactyl GX (Secret) SM - Unified Minds Holofoil $5.40 $6.48 Aether Foundation Employee Hidden Fates: Shiny Vault Holofoil $3.32 $3.98 Aggron EX XY - Primal Clash Holofoil $0.97 $1.16 Aggron EX (153 Full Art) XY - Primal Clash Holofoil $4.27 $5.12 Air Balloon (Secret) SWSH01: Sword & Shield Base Set Holofoil $4.57 $5.48 Alakazam EX XY - Fates Collide Holofoil $1.28 $1.53 Alakazam EX (Full Art) XY - Fates Collide Holofoil $3.37 $4.04 Alakazam EX (Secret) XY - Fates Collide Holofoil $5.32 $6.38 Alakazam V (Full Art) SWSH04: Vivid Voltage Holofoil $3.92 $4.70 Allister (Full Art) SWSH04: Vivid Voltage Holofoil $5.70 $6.84 Allister (Secret) SWSH04: Vivid Voltage Holofoil $7.99 $9.58 Alolan Exeggutor GX SM - Crimson Invasion Holofoil $0.80 $0.96 Alolan Exeggutor GX (Full Art) SM - Crimson Invasion -

Round 05 - Tossups Written and Edited by Luc Wetherbee and Daniel Xu with Contributions from Harris Bunker and the Cornell Quizbowl Team

PACENSC 2018 - Round 05 - Tossups Written and edited by Luc Wetherbee and Daniel Xu With contributions from Harris Bunker and the Cornell Quizbowl Team 1. This Pokémon emerged as an anti-metagame pick due to its ability to execute a strategy called the “Space Animal Slayer.” When this Pokémon is traded from a Generation I to a Generation II game, it holds a Polkadot Bow. Although this Pokémon is Normal-type, it shares a Pokémon category with Qwilfish. This Pokémon’s evolved form grants you access to locations such as Mt. Cleft and Peanut Swamp in (*) Red and Blue Rescue Team. In one game, this Pokémon is notable for being able to perform a strategy called the “Wall of Pain.” This Pokémon can, unusually, cause massive amounts of damage in that game by using Rest. This Pokémon’s Japanese name translates literally to “Pudding.” For ten points, name this longtime playable character in Super Smash Bros., a Pokémon best-known for its ability to Sing. ANSWER: Jigglypuff <DX> 2. After you enter the Hall of Fame, an item with this name can be bought for 500 Poké at the Market Stall in Two Island. It’s not Solaceon Town, but the aesthetic Seal Case can be obtained at a place with this name. Surprisingly, an item with this name is the only one available at Sinnoh’s Cafe Cabin. The TM for Snore or Natural Gift is obtained after healing a sick Pokémon with this name by (*) feeding it seven Oran Berries. That Pokémon’s species is a rare encounter west of Ecruteak City. -

Instructions: Read Carefully! 1

EECS 183 Winter 2012 Exam 2 Part 1 17 questions @ 5 pts each max 80 points (so you get one question on us) Closed Book Closed Notes Closed Electronic Devices Closed Neighbor Turn off Your Cell Phones Multiple Choice Questions Form 1 Instructions: Read Carefully! 1. On the scantron sheet, bubble & enter your name and UMID and Form number and sign your name to indicate the honor pledge below: I have neither given nor received aid on this examination, nor have I concealed any violations of the Honor Code. 2. This is a closed book exam. You may not refer to any materials during the exam. 3. Please turn off your cell phones before the start of the exam. 4. Some questions are not simple, therefore, read carefully. 5. Assume all code and code fragments compile, unless otherwise specified. 6. Assume/use only the standard ISO/ANSI C++. 1 1) Ponder the following code fragment int level; for (level = 10; level < 20; level += 2) { // do nothing } cout << level; What does the above code print? A) 2 B) 10 C) 20 D) 18 E) the code does not compile 2) Ponder the following code fragment for (int level = 10; level < 20; level += 2) { // do nothing } cout << level; What does the above code print? A) 2 B) 10 C) 20 D) 18 E) the code does not compile 2 3) Given the following function definition: void missingNo(int& item) { item *= 10; } Ponder the following code fragment int rareCandies = 4; while (rareCandies != 100) { missingNo(rareCandies); } cout << rareCandies; What does the above code print? A) 4 B) 100 C) 40 D) 400 E) the code enters an infinite loop 4) Ponder the following C++ function (calculate carefully!) int adjustLife(int& health, int damage) { health = health + damage; return health; } If a variable life of type int is initialized to 100 what does the C++ expression adjustLife(life, -20) + adjustLife(life, -40) evaluate to? A) 100 B) 120 C) 140 D) 40 E) -60 3 5) What does the following code fragment print? void levelUp(int level) { level++; } int main() { int levelOfMeowth = 27; cout << "Current Level : " << levelOfMeowth << ". -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Anime's Media Mix: Franchising Toys and Characters in Japan

blo gs.lse.ac.uk http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lsereviewofbooks/2013/01/12/book-review-animes-media-mix-franchising-toys-and-characters-in- japan/ Book Review: Anime’s Media Mix: Franchising Toys and Characters in Japan by blog admin January 12, 2013 In Anime’s Media Mix, author Marc Steinberg shows that anime is far more than a style of Japanese animation. Engaging with film, animation, and media studies, as well as analysis of consumer culture and theories of capitalism, Steinberg offers the first sustained study of the Japanese mode of convergence that informs global media practices to this day. Casey Brienza finds this is a very flawed book but nevertheless, a very good one. Anime’s Media Mix: Franchising Toys and Characters in Japan. Marc Steinberg. University of Minnesota Press. 2012. Find this book: If you are a child—or the parent of a child—you probably recognize the bright yellow rodent able to shoot lightning bolts at its enemies. It is, of course, Pikachu, the ubiquitous of f icial mascot of the Pokémon multimedia f ranchise, a global juggernaut which includes video games, trading cards, televised cartoons, comic books, plush toys, and much, much more. However, Pikachu is f ar more than just a poster-child f or capitalist accumulation; it is, according to Marc Steinberg, a ‘character,’ the essential tie binding the disparate parts of the f ranchise together to each other and to consumers, as well as consumers to each other. The prolif eration of particular creative properties across multiple mediated platf orms has been called many things, with ‘synergy,’ ‘convergence,’ and ‘transmedia’ among the most popular in the west. -

Pokémon, Cultural Practice and Object Networks Jason Bainbridge

iafor The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Volume I – Issue I – Winter 2014 IAFOR Publications Executive Editor: Joseph Haldane The International Academic Forum The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Editor Seiko Yasumoto, University of Sydney, Australia Associate Editor Jason Bainbridge, Swinburne University, Australia Advisory Editors Michael Curtin, University of California, Santa Barbara, United States Terry Flew, Queensland University of Technology, Australia Michael Keane, Queensland University of Technology, Australia Editorial Board Robert Hyland, BISC, Queens University Canada, United Kingdom Dong Hoo Lee, Incheon University, Korea Ian D. McArthur, The University of Sydney, Australia Paul Mountfort, Auckland University of Technology, New Zealand Jin Nakamura, Tokyo University, Japan Tetsuya Suzuki, Meiji University, Japan Yoko Sasagawa, Kobe Shinwa Womens University, Japan Fang Chih Irene Yang, National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan Published by the International Academic Forum (IAFOR), Japan Executive Editor, IAFOR Publications: Joseph Haldane Editorial Assistance: Lindsay Lafreniere IAFOR Publications, Sakae 1-16-26-201, Naka-ward, Aichi, Japan 460-0008 The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Volume I – Issue I – Winter 2014 IAFOR Publications © Copyright 2014 ISSN: 2187-6037 Online: http://iafor.org/iafor/publications/iafor-journals/iafor-journal-of-asian-studies/ Cover image by: Norio NAKAYAMA/Flickr https://www.flickr.com/photos/norio-nakayama/11153303693 The IAFOR Journal of Asian Studies Volume I – Issue I – Winter 2014 Edited by -

Pokémon Silver Version 2001

PLEASE TAKE ONE For beginners and veterans alike! Pokémon Gold Version Pokémon Silver Version 2001 02 Pokémon Gold Version and Pokémon Silver Version – 9 years on Pokémon Gold Version and Pokémon Silver Version were fi rst released for the Game Boy in 2001. These new titles for the Nintendo DS are based on the storyline from Pokémon Gold and Silver Versions, but come packed with all sorts of new features. Pokémon Gold Version Pokémon HeartGold Version Pokémon Silver Version 2001 Pokémon SoulSilver Version 2010 01 Starter Pokémon 1 What are Pokémon? You can now select your bicycle, Pokédex Pokémon are fascinating creatures harbouring many mysteries. Some live in harmony fishing rod and other handy items with humans, while others live on grassy plains, caves or the ocean. Taking on the role of a Pokémon Trainer, players will encounter many different Pokémon and can recruit them by “catching” them, before nurturing and raising them. Players will grow in skill and experience as they embark on all sorts of adventures with ease from the Menu Screen. and battle other Pokémon Trainers with the help of their Pokémon team. The ultimate This will help you on your journey. goal is to complete their Pokédex, and take a shot at becoming the Pokémon League Champion (one of the strongest Trainers in the world). Boy Girl Fire Mouse Pokémon Leaf Pokémon Big Jaw Pokémon Cyndaquil Chikorita Totodile The first Pokémon you get: The player can choose one of these three Pokémon The player can choose to play Main Character: as one of these two characters. -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

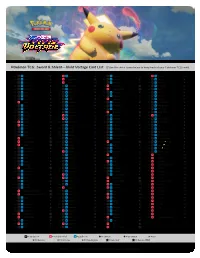

Sword & Shield—Vivid Voltage Card List

Pokémon TCG: Sword & Shield—Vivid Voltage Card List Use the check boxes below to keep track of your Pokémon TCG cards! 001 Weedle ● 048 Zapdos ★H 095 Lycanroc ★ 142 Tornadus ★H 002 Kakuna ◆ 049 Ampharos V 096 Mudbray ● 143 Pikipek ● 003 Beedrill ★ 050 Raikou ★A 097 Mudsdale ★ 144 Trumbeak ◆ 004 Exeggcute ● 051 Electrike ● 098 Coalossal V 145 Toucannon ★ 005 Exeggutor ★ 052 Manectric ★ 099 Coalossal VMAX X 146 Allister ◆ 006 Yanma ● 053 Blitzle ● 100 Clobbopus ● 147 Bea ◆ 007 Yanmega ★ 054 Zebstrika ◆ 101 Grapploct ★ 148 Beauty ◆ 008 Pineco ● 055 Joltik ● 102 Zamazenta ★A 149 Cara Liss ◆ 009 Celebi ★A 056 Galvantula ◆ 103 Poochyena ● 150 Circhester Bath ◆ 010 Seedot ● 057 Tynamo ● 104 Mightyena ◆ 151 Drone Rotom ◆ 011 Nuzleaf ◆ 058 Eelektrik ◆ 105 Sableye ◆ 152 Hero’s Medal ◆ 012 Shiftry ★ 059 Eelektross ★ 106 Drapion V 153 League Staff ◆ 013 Nincada ● 060 Zekrom ★H 107 Sandile ● 154 Leon ★H 014 Ninjask ★ 061 Zeraora ★H 108 Krokorok ◆ 155 Memory Capsule ◆ 015 Shaymin ★H 062 Pincurchin ◆ 109 Krookodile ★ 156 Moomoo Cheese ◆ 016 Genesect ★H 063 Clefairy ● 110 Trubbish ● 157 Nessa ◆ 017 Skiddo ● 064 Clefable ★ 111 Garbodor ★ 158 Opal ◆ 018 Gogoat ◆ 065 Girafarig ◆ 112 Galarian Meowth ● 159 Rocky Helmet ◆ 019 Dhelmise ◆ 066 Shedinja ★ 113 Galarian Perrserker ★ 160 Telescopic Sight ◆ 020 Orbeetle V 067 Shuppet ● 114 Forretress ★ 161 Wyndon Stadium ◆ 021 Orbeetle VMAX X 068 Banette ★ 115 Steelix V 162 Aromatic Energy ◆ 022 Zarude V 069 Duskull ● 116 Beldum ● 163 Coating Energy ◆ 023 Charmander ● 070 Dusclops ◆ 117 Metang ◆ 164 Stone Energy ◆ -

Super Smash Bros. Melee from a Casual Game to a Competitive Game

Playing with the script: Super Smash Bros. Melee From a casual game to a competitive game Joeri Taelman 4112334 New Media and Digital Culture Master thesis Supervisor Dr. Stefan Werning Second reader Dr. René Glas 8th of February, 2015 Abstract This thesis studies the interaction between developers and players outside of game design. It does so by using the concept of ‘playing with the script’. René Glas’ Battlefields of Negotiations (2013) studies the interaction between those two stakeholders for a networked game. In Glas’ case of World of Warcraft, it is networked play, meaning that the developer (Blizzard) has control over the game’s servers and thus can implement the results of negotiations by changing the rules continuously. Playing with the script can be seen as an addition to ‘battlefields of negotiation’, and explains the negotiations outside of the game’s structure for a non-networked game and how these negotiations affect the game series’ continuum. Using a frame analysis, this thesis explores the interaction between Nintendo and the players of the game Super Smash Bros. Melee as participatory culture. The latter is possible by going back and forth between the script inscribed in the object by developers and its displacement by the users, in which the community behind the game, ‘the smashers’, transformed the casual nature of the game into a competitive one. 2 Acknowledgments It took a while to realize this New Media and Digital Culture master thesis for Utrecht University. Not only during, but also before the time of writing I have been helped and influenced by a couple of people. -

Pokémon Quiz!

Pokémon Quiz! 1. What is the first Pokémon in the Pokédex? a. Bulbasaur b. Venusaur c. Mew 2. Who are the starter Pokémon from the Kanto region? a. Bulbasaur, Pikachu & Cyndaquil b. Charmander, Squirtle & Bulbasaur c. Charmander, Pikachu & Chikorita 3. How old is Ash? a. 9 b. 10 c. 12 4. Who are the starter Pokémon from the Johto region? a. Chikorita, Cyndaquil & Totadile b. Totodile, Pikachu & Bayleef c. Meganium, Typhlosion & Feraligatr 5. What Pokémon type is Pikachu? a. Mouse b. Fire c. Electric 6. What is Ash’s last name? a. Ketchup b. Ketchum c. Kanto 7. Who is Ash’s starter Pokémon? a. Jigglypuff b. Charizard c. Pikachu 8. What is Pokémon short for? a. It’s not short for anything b. Pocket Monsters c. Monsters to catch in Pokéballs 9. Which Pokémon has the most evolutions? a. Eevee b. Slowbro c. Tyrogue 10. Who are in Team Rocket? a. Jessie, James & Pikachu b. Jessie, James & Meowth c. Jessie, James & Ash 11. Who is the Team Rocket Boss? a. Giovanni b. Jessie c. Meowth 12. What is Silph Co? a. Prison b. Café c. Manufacturer of tools and home appliances 13. What Pokémon has the most heads? a. Exeggcute b. Dugtrio c. Hydreigon 14. Who are the Legendary Beasts? a. Articuno, Moltres & Arcanine b. Raikou, Suicune & Entei c. Vulpix, Flareon & Poochyena 15. Which Pokémon was created through genetic manipulation? a. Mew b. Mewtwo c. Tasmanian Devil 16. What is the name of the Professor who works at the research lab in Pallet Town? a. Professor Rowan b. Professor Joy c. -

Pummelo Stadium Thundershock

in Thundershock Pummelo Stadium 4475382_TXT_v2.indd75382_TXT_v2.indd iiiiii 111/11/161/11/16 44:22:22 PPMM If you purchased this book without a cover, you should be aware that this book is stolen property. It was reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher, and neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this “stripped book.” ©2017 The Pokémon Company International. ©1997-2017 Nintendo, Creatures, GAME FREAK, TV Tokyo, ShoPro, JR Kikaku. TM, ® Nintendo. All rights reserved. Published by Scholastic Inc., Publishers since 1920. SCHOLASTIC and associated logos are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of in Scholastic Inc. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content. Thundershock No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher. For Pummelo Stadium information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., Attention: Permissions Department, 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. This book is a work of fi ction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fi ctitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. ISBN 978-1-338-17598-1 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 17 18 19 20 21 Printed in the U.S.A. 40 First printing 2017 4475382_TXT_v2.indd75382_TXT_v2.indd iviv 111/11/161/11/16 44:22:22 PPMM in Thundershock Pummelo Stadium Adapted by Tracey West Scholastic Inc.