Jack Marshall – Biography by Kim Newth 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cm 9437 – Armed Forces' Pay Review Body – Forty-Sixth Report 2017

Appendix 1 Pay16: Pay structure and mapping1 Trade Supplement Placement (TSP) The Trades within each Supplement are listed alphabetically, and colour coded to represent each Service (dark blue for Naval Service, red for Army, light blue for RAF and purple for the Allied Health Professionals). Supplement 1 Supplement 2 Supplement 3 Aerospace Systems Operating ARMY AAC Groundcrew Sldr Aircraft Engineering (Avionics) and Air Traffic Control including including Aircraft Engineering RAF RAF Air Cartographer Aerospace Systems Operator/Manager, RAF Technician, Aircraft Technician Flight Operations Assistant/Manager RN/RM Comms Inf Sys inc SM & WS (Avionics) and Aircraft Maintenance ARMY Army Welfare Worker ARMY Crewman 2 Mechanic (Avionics) ARMY Custodial NCO AHP Dental Hygienist Air Engineering (Mechanical) including Aircraft Engineering AHP Dental Nurse AHP Dental Technician RAF Technician, Aircraft Technician RN/RM Family Services Aircraft Engineering (Weapon) (Mechanical) and Aircraft Maintenance RAF including Engineering Weapon and (Mechanical) RAF Firefighter Weapon Technician Air Engineering Technician including AHP Health Care Assistant General Engineering including Aircraft Engineering Technician, RN/RM Hydrography & MET (including legacy General Engineering Technician, Aircraft Technician (Avionics) & Aircraft RN/RM NA(MET)) RAF General Technician Electrical, General Maintenance Mechanic (Avionics) Technician (Mechanical) and General RN/RM Logs (Writer) inc SM RN/RM Aircrewman (RM, ASW, CDO) Technician Workshops Logistics (Caterer) -

Rare Books 6 December 2017 40 40

Rare Books 6 December 2017 40 40 45 36 60 37 33 33 69 24 68 38 38 12 47 42 39 39 228 RARE BOOK AUCTION Wednesday 6th December 2017 at 12 noon. VIEWING: Saturday & Sunday 2nd and 3rd December 2017 11.00am – 4.00pm Monday 4th December 2017 9.00am – 5.00pm Tuesday 5th December 2017 9.00am – 5.00pm Art + Objects final book sale of the year is a diverse collection of 400 lots offering some rare and important items. They include two examples of incunabula, one in the original medieval chain binding ‘Juvenalis Argumenta Satyrarum’ [Nuremberg 1497] the other, one of three known examples of an illuminated ‘Book of Hours’ [ca 1425-1450] in private hands in New Zealand. An archive of original letters and documents from John Brown a well -known advocate, of searches, relating to the Franklin Expedition, includes letters from Lady Jane Franklin, Robert McCormick and several others by Captains of the various expedition which went in search of Sir John Franklin. A collection of New Zealand & English antiquarian natural history books including W.L. Bullers ‘A History of the Birds of New Zealand’ 1st & 2nd editions; Pennant’s History of Quadrupeds [1781]. James Busby’s ‘Culture of the Vine in New South Wales’. Ln 1840. George Hamiltons ‘Voyage Round the World in H.M Frigate Pandora’, [W.Phorson 1793] Capts Cook and King – ‘A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean…’ [London 1785] A large section of hunting books including by T.E. Donne and others. A superb 19th century finely carved inanga Hei Tiki A very scarce copy of George French Angas’s ‘The New Zealanders Illustrated’, still in the printed wrappers as originally published Original rugby cap from ‘The Invincibles’ tour of England 1924 New Zealand documents feature an historic archive of documents relating to John Bryce and the ‘Incident at Handley’s woolshed’, it includes dairy, letters and documents. -

A Pictorial Record of the Combat Duty of Patrol Bombing Squadron One Hundred Nine in the Western Pacific, 20 April 1945-15 August 1945 Theodore Manning Steele

Bangor Public Library Bangor Community: Digital Commons@bpl World War Regimental Histories World War Collections 1946 A pictorial record of the combat duty of Patrol Bombing Squadron One Hundred Nine in the Western Pacific, 20 April 1945-15 August 1945 Theodore Manning Steele Follow this and additional works at: http://digicom.bpl.lib.me.us/ww_reg_his Recommended Citation Steele, Theodore Manning, "A pictorial record of the combat duty of Patrol Bombing Squadron One Hundred Nine in the Western Pacific, 20 April 1945-15 August 1945" (1946). World War Regimental Histories. 101. http://digicom.bpl.lib.me.us/ww_reg_his/101 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the World War Collections at Bangor Community: Digital Commons@bpl. It has been accepted for inclusion in World War Regimental Histories by an authorized administrator of Bangor Community: Digital Commons@bpl. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 110° ato• 0 c H N A ~ DOES N01 ~ u- tlnl~ ~lifO 71HA ~' .... \ \ "''".!... ~ ', '~ \ ' ' ' .... ' .... .... ~ " ',"-'. ', \ ' ' ... \ ' ' ' ... ' \ • ·MMH ' ', \ ' ~... \ ' ' ' ~ '' .. \ ' ...... ' ':..\ INDO ':..- -- -rat-~1»4.. CHlNA ..... ---- ' . --- ---~-- ....... ~ :)-- -- --- -<.- --- --- GUAM ----- -~:------- --).. ~- ----- ->-- - --- I ·~· ·:: \~:' TRUK :l ~ J.;. A PICTORIAL RECORD of the combat duty of PATROL BOMBING SQUADRON ONE HUNDRED NINE in the _Western Pacific, 20 April1945- 15 August 1945 DEDICATED ( ' ' .. C.0 4" • . • • .. .. .. .. .~ · .. .: .. :: ~ .. :::: .. ; ~ ;."~ · . .. ~ ~ "' ... to the officers and men of the squadron who ' Ill,,. •• .. ...... ... ' .a . ... .. == ~ : > <~ :~ .£ ::~ .. ! .. :· . .. .. ~ . .. - .. gave their lives that we may live in peace II .,.' • &. ~ " Copyright 1946 By Lieutenant Theodore M. Steele, USNR General Offset Co., Inc., New York 13, N.Y. "SKIPPER" LIEUTENANT COMMANDER GEORGE LEIGHTON HICKS USNR Executive Officer 2 August 1943-2 September 1944 Commanding Officer .... ... ........ ., . ~ .. .. .... .. 6 December 1944- 19 October 1945 . -

Jack Marshall, DFC Service No: NZ391865

1 Jack Marshall, DFC Service No: NZ391865 AIR GUNNER Biography by Kim Newth A keenness and desire to engage the enemy were qualities displayed at all times by Flying Officer Jack Marshall, according to his citation for the Distinguished Flying Cross on 12 April 19431. A successful operational career as an air gunner also came at a price, draining reserves of courage and endurance through many long hours of fear, numbing cold and fatigue on life-threatening sorties2. This is his story. ********************************************************* Growing up in the city of his birth, Jack Marshall recalls a happy, relatively trouble-free childhood. He was born in London on 1 August 1920 to English parents, Herbert and Edith Marshall and was the youngest of three brothers in the family. When Jack was in his teens, his father would commute to work as a telegraphist at the Central Telegraph Office as the family had by then moved to a home just out of London. Jack’s school years passed uneventfully and his first job was as an apprentice wrought-iron worker3. Jack’s father, Herbert Marshall, had served as a sapper in the First World War and had also fought in the Boer War. Jack remembers hearing about the battlefields of Flanders and Passchendaele from his father4, but never thought he would be confronted with similar risks even though the threat of war began to loom again through the 1930s. In 1937, Herbert elected to retire early. By this time, his other two sons had left England to join a farming programme in New Zealand. -

Autumn 07 Cover

ORDERS, DECORATIONS AND MEDALS 4-5 DECEMBER 2017 LONDON GROUP CHAIRMAN AND CEO Olivier D. Stocker YOUR SPECIALISTS STAMPS UK - Tim Hirsch FRPSL David Parsons Nick Startup Neill Granger FRPSL Dominic Savastano George James Ian Shapiro (Consultant) USA - George Eveleth Fernando Martínez EUROPE - Guido Craveri Fernando Martínez CHINA - George Yue (Consultant) Alan Ho COINS UK - Richard Bishop Tim Robson Gregory Edmund Robert Parkinson Lawrence Sinclair Barbara Mears John Pett (Consultant) USA - Muriel Eymery Greg Cole Stephen Gol dsmith (Special Consultant) CHINA - Kin Choi Cheung Paul Pei Po Chow BANKNOTES UK - Barnaby Faull Andrew Pattison Thomasina Smith USA - Greg Cole Stephen Goldsmith (Special Consultant) CHINA - Kelvin Cheung Paul Pei Po Chow ORDERS, DECORATIONS, MEDALS & MILITARIA UK - David Erskine-Hill Marcus Budgen USA - Greg Cole BONDS & SHARES UK - Mike Veissid (Consultant) Andrew Pattison Thomasina Smith USA - Stephen Goldsmith (Special Consultant) EUROPE - Peter Christen (Consultant) CHINA - Kelvin Cheung BOOKS UK - Emma Howard Nik von Uexkull AUTOGRAPHS USA - Greg Cole Stephen Goldsmith (Special Consultant) WINES CHINA - Angie Ihlo Fung Guillaume Willk-Fabia (Consultant) SPECIAL COMMISSIONS UK - Ian Copson Edward Hilary Davis YOUR EUROPE TEAM (LONDON - LUGANO) Directors Tim Hirsch Anthony Spink Auction & Client Management Team Mira Adusei-Poku Rita Ariete Katie Cload Dora Szigeti Nik von Uexkull Tom Hazell John Winchcombe Viola Craveri Finance Alison Bennet Marco Fiori Mina Bhagat Dennis Muriu Veronica Morris Varranan Somasundaram -

Army Abbreviations

Army Abbreviations Abbreviation Rank Descripiton 1LT FIRST LIEUTENANT 1SG FIRST SERGEANT 1ST BGLR FIRST BUGLER 1ST COOK FIRST COOK 1ST CORP FIRST CORPORAL 1ST LEADER FIRST LEADER 1ST LIEUT FIRST LIEUTENANT 1ST LIEUT ADC FIRST LIEUTENANT AIDE-DE-CAMP 1ST LIEUT ADJT FIRST LIEUTENANT ADJUTANT 1ST LIEUT ASST SURG FIRST LIEUTENANT ASSISTANT SURGEON 1ST LIEUT BN ADJT FIRST LIEUTENANT BATTALION ADJUTANT 1ST LIEUT REGTL QTR FIRST LIEUTENANT REGIMENTAL QUARTERMASTER 1ST LT FIRST LIEUTENANT 1ST MUS FIRST MUSICIAN 1ST OFFICER FIRST OFFICER 1ST SERG FIRST SERGEANT 1ST SGT FIRST SERGEANT 2 CL PVT SECOND CLASS PRIVATE 2 CL SPEC SECOND CLASS SPECIALIST 2D CORP SECOND CORPORAL 2D LIEUT SECOND LIEUTENANT 2D SERG SECOND SERGEANT 2LT SECOND LIEUTENANT 2ND LT SECOND LIEUTENANT 3 CL SPEC THIRD CLASS SPECIALIST 3D CORP THIRD CORPORAL 3D LIEUT THIRD LIEUTENANT 3D SERG THIRD SERGEANT 3RD OFFICER THIRD OFFICER 4 CL SPEC FOURTH CLASS SPECIALIST 4 CORP FOURTH CORPORAL 5 CL SPEC FIFTH CLASS SPECIALIST 6 CL SPEC SIXTH CLASS SPECIALIST ACTG HOSP STEW ACTING HOSPITAL STEWARD ADC AIDE-DE-CAMP ADJT ADJUTANT ARMORER ARMORER ART ARTIF ARTILLERY ARTIFICER ARTIF ARTIFICER ASST BAND LDR ASSISTANT BAND LEADER ASST ENGR CAC ASSISTANT ENGINEER ASST QTR MR ASSISTANT QUARTERMASTER ASST STEWARD ASSISTANT STEWARD ASST SURG ASSISTANT SURGEON AUX 1 CL SPEC AUXILARY 1ST CLASS SPECIALIST AVN CADET AVIATION CADET BAND CORP BAND CORPORAL BAND LDR BAND LEADER BAND SERG BAND SERGEANT BG BRIGADIER GENERAL BGLR BUGLER BGLR 1 CL BUGLER 1ST CLASS BLKSMITH BLACKSMITH BN COOK BATTALION COOK BN -

The New Zealand Gazette. ~ Vj7

APRIL 16.] THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. ~ VJ7_ Appointments and Promotions of Officers of the Royal New EQUIPMENT BRANCH, SECTION 'I. Zealand Air Force. Appointnrents, The undermentioned are 'granted temporary commissions in the rank of Pilot Officer. Dated 23rd February, 1942 :- Air. Department, Wellington, 8th April, 1942. As EQUIPMENT OFFICERS. · IS Excellency the Governor-General has been pleased NZ 639135 Sergeant Howard-Cottle.MuLLENGER; H to approve of the following appointments and pro NZ 40313 Corporal Jack Warwick WILSON. motions of officers of the Royal New Zealand Air Force :-'-- NZ 40290 Corporal Harry Francis BoYs. NZ 1456 Evin Ross CFRTIS. NZ 1457 Charles Magnus LENNIE. GENERAL DUTIES BRANCH. NZ 1458 . Peter George HARLE. Appointments. , NZ 1459 Stanley Burnell BROWNE, The undermentioned are granted temporary commissions NZ 1460 Alvar Franklin RE.AD. in the rank of Pilot Officer :- NZ 437031 Sergeant Norman Hillary MEYERS. NZ 1461 Alfred Cecil KELLETT. As PILOTS. Dated 20th Ma,rch, 1942- As -AccouNT ANT 0FF!CERS. NZ 40248 Flight Sergeant Robert Keith WALKER. NZ 40144 Corporal John.Hill SUTHERLAN)', NZ 403789 Sergeant Hadyn Louis HoPE. · NZ 39791 Sergeant Ian Keir MARTIN. · NZ 411371 Sergeant Jack McGifford CLELAND. NZ 39995 Sergeant Henry Aulton DAVISON. Dated 24th March, 1942- NZ 391527 Sergeant William John )\1:0RLEY. NZ 403447 Sergeant Owen Terence HANNIGAN. NZ 38193 Flight Sergeant John Martin MoLLoY.' NZ 404012 Sergeant William Keith WILBY. NZ 402512 Sergeant Richard Warrnn BARTLEY. EQUIPMENT BRANCH,_ SECTION II. NZ 404922 Sergeant William James Stanley MONKS. Appointments. The undermentioned are granted temporary commissions As Am OBSERVERS. in the rank of Pilot Officer (on prob.) :- · Dated 19th March, 1942- NZ 411509 Sergeant Clive Gaby IBBOTSON. -

RAF Stories: the First 100 Years 1918 –2018

LARGE PRINT GUIDE Please return to the box for other visitors. RAF Stories: The First 100 Years 1918 –2018 Founding partner RAF Stories: The First 100 Years 1918–2018 The items in this case have been selected to offer a snapshot of life in the Royal Air Force over its first 100 years. Here we describe some of the fascinating stories behind these objects on display here. Case 1 RAF Roundel badge About 1990 For many, their first encounter with the RAF is at an air show or fair where a RAF recruiting van is present with its collection of recruiting brochures and, for younger visitors, free gifts like this RAF roundel badge. X004-5252 RAF Standard Pensioner Recruiter Badge Around 1935 For those who choose the RAF as a career, their journey will start at a recruiting office. Here the experienced staff will conduct tests and interviews and discuss options with the prospective candidate. 1987/1214/U 5 Dining Knife and Spoon 1938 On joining the RAF you would be issued with a number of essential items. This would have included set of eating irons consisting of a knife, fork and spoon. These examples have been stamped with the identification number of the person they were issued to. 71/Z/258 and 71/Z/259 Dining Fork 1940s The personal issue knife, fork and spoon set would not always be necessary. This fork would have been used in the Sergeant’s Mess at RAF Henlow. It is the standard RAF Nickel pattern but has been stamped with the RAF badge and name of the station presumably in an attempt to prevent individuals claiming it as their personal item. -

News Letter March 17 Draft Print Copy Final B.Pub

ASSOCIATION MAILING ADDRESS: R REGT C ASSOCIATION WEB SITE: The Royal Regiment of Canada www.rregtc‐assoc.org 660 Fleet Street TORONTO ON M5V 1A9 The Royal Regiment of Canada Associaon 10th Royal Grenadiers The Toronto Regiment (3rd Bn CEF 1862 ICH DIEN March 2017 PRESIDENT PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Hello and welcome everyone to the spring 2017 edi‐ CWO (ret’d) Ross Atkinson on of “Ich Dien”. By the me you read this, the first Regimental Birthday Ball 519‐278‐1779 [email protected] sponsored by the Associaon will be in the history books. For those who aended, I’m sure those extra dance lessons came in handy. We delayed this VICE PRESIDENT & edion, to be sure to include some pictures from the event. PAST PRESIDENT WO (ret’d) Glen Moore The results of the 2017 Elecon of Execuve are included within these hal‐ 647‐960‐1005 [email protected] lowed pages along with a picture, for those in the furthest reaches of the Em‐ pire may put a face to a name. I am honoured to be able to connue my role as SECRETARY your President, along with most of the past Execuve intact. It is due to the Leo Afonso 905‐697‐3865 hard work and dedicaon of my fellow exec members that we can connue to [email protected] serve the Associaon and the Regimental Family. TREASURER We have had an excing opportunity offered to us by Veterans Affairs to have Capt (ret’d) Dan Joyce an Associaon member join them as part of the official party for the 100th An‐ 905‐337‐7142 [email protected] niversary of Vimy Ridge. -

Guide to Abbreviations on Listing (PDF)

Guide to Abbreviations on Listing Branch Abbreviation Description AAF Army Air Force ARMY United States Army CA C‐ARMY Canadian Army CG Civil Civilian ColAr Colonial Army Indian MILI Colonial Militia NAVY United States Navy RANG Colonial Ranger USMC United States Marine Corps Rank Abbreviation Description 1LT First Lieutenant 1SG First Sergeant 2LT Second Lieutenant AM3 Aircraft Structural Mechanic 3rd Class AMM2 Aviation Machinist's Mate 2nd Class AV CAviationC Aviation Cadet AVO3 Avionics Officer AvR3 AvRd3 AW2 Aviation ASW Operator 2nd Class BM1 Boatswain's Mate 1st Class CAPT / CPT Captain CPL Corporal CTM Cryptologic Technician CTO2 Cryptologic Technician 2nd Class DC2 Damage Controlman 2nd Class ELM3 ENS Ensign (Colonial, Lieutenant 2nd Class) FL O Flight Officer FO 1 GM3 Gunner's Mate 3rd Class GuM Gunner's Mate HA2 LT Lieutenant LTC Lieutenant Colonel LTJG Lieutenant, Junior Grade M1C Mechanic 1st Class www.co.armstrong.pa.us MAJ Major MECH Mechanic MM1 Machinist's Mate First Class MMM MP5 MSG Master Sergeant MUSC Musician PFC Private First Class PO2 Petty Officer 2nd Class (Canadian Forces) PSG Platoon Sergeant PVT Private QMS Quartermaster Sergeant Rad1 Rad3 S1C Se2 SEA SGT Sergeant SM1 Signalman 1st Class SM2 Signalman 2nd Class SOL Soldier (Colonial Militia) SP4 Specialist 4th Class SRe Seaman Recruit SSG Staff Sergeant SURG Surgeon T4 TEC4 Technician 4th Class TEC5 Technician 5th Class TSG Technical Sergeant Status Abbreviation Description DNB Died, Non‐Battle DNBA DNBG DNBI Died, Non‐Battle (Influenza) DOW Died of Wounds DOWG KIA Killed in Action KIAF Killed in Action (Findings of Death) KIAM Killed in Action (Missing) KIAS Killed in Action (Sinking) MIA Missing in Action POWd Prisoner of War (Died in Captivity) www.co.armstrong.pa.us. -

Master Gunner George Marshall U.S.N

1 Master Gunner George Marshall U.S.N. Demetrios Constantinos Andrianis 2 Early Life……………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Brig Jefferson………………………………………………………………...…………………………….....4 Sloop-of-War Erie.…...…………………………………………..……..…………………………………....5 Gosport Navy Yard (1820-1824)………………………………………………………….………………… 6 North Carolina 74……….……………………………………………………………………………………8 Washington Navy Yard….……………………………………………………………………………….....10 Gosport Navy Yard (1832-1855)………………………...………………………………………………….11 Memorial ……………………………………………………………………………………………………13 Notes…………………………...…………………………………….……………………………...…........16 Contact: [email protected] Updated: May 31, 2021 May 18, 2021 All Rights Reserve 3 Early Life George Marshall was a Greek-American naval hero. He served during the War of 1812. He was an author, artillery scientist, chemist, and naval educator. Marshall was a warrant officer. His specialization was gunnery. He wrote Marshall's Practical Marine Gunnery. Marshall eventually became a master gunner in the U.S. Navy. Master was the highest rank a gunner could obtain. His son and sons-in-law also became gunners. He was one of the most important naval gunners in U.S. history. He helped build the framework of U.S. naval gunnery education. His book on naval gunnery outlined, artillery propulsion, over fifty chemical mixtures for pyrotechnics, Greek fire, smoke bombs, three different chemical mixtures for dying clothes, and the chemical composition of a stain removal solution. The book also lists the chemical names of dozens of different substances used in the early nineteenth century predating Dmitri Mendeleev’s periodic table and the standard chemical nomenclature of the 20th century. Marshall was born on the Greek island of Rhodes in 1781. Marshall was in the United States around the time America fought the First Barbary War. The country was 31 years old. He married Phillippi Higgs. -

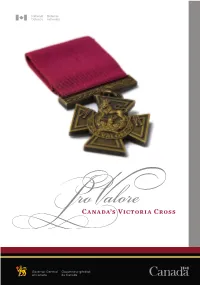

Canada's Victoria Cross

Canada’s Victoria Cross Governor General Gouverneur général of Canada du Canada Pro Valore: Canada’s Victoria Cross 1 For more information, contact: The Chancellery of Honours Office of the Secretary to the Governor General Rideau Hall 1 Sussex Drive Ottawa, ON K1A 0A1 www.gg.ca 1-800-465-6890 Directorate of Honours and Recognition National Defence Headquarters 101 Colonel By Drive Ottawa, ON K1A 0K2 www.forces.gc.ca 1-877-741-8332 Art Direction ADM(PA) DPAPS CS08-0032 Introduction At first glance, the Victoria Cross does not appear to be an impressive decoration. Uniformly dark brown in colour, matte in finish, with a plain crimson ribbon, it pales in comparison to more colourful honours or awards in the British or Canadian Honours Systems. Yet, to reach such a conclusion would be unfortunate. Part of the esteem—even reverence—with which the Victoria Cross is held is due to its simplicity and the idea that a supreme, often fatal, act of gallantry does not require a complicated or flamboyant insignia. A simple, strong and understated design pays greater tribute. More than 1 300 Victoria Crosses have been awarded to the sailors, soldiers and airmen of British Imperial and, later, Commonwealth nations, contributing significantly to the military heritage of these countries. In truth, the impact of the award has an even greater reach given that some of the recipients were sons of other nations who enlisted with a country in the British Empire or Commonwealth and performed an act of conspicuous Pro Valore: Canada’s Victoria Cross 5 bravery.