Connecting My Passion of Music to the Buddha Passion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: the Life Cycle of the Child Performer

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: The life cycle of the child performer by Lyndsay Barnbrook A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Humanities Faculty School of Music April 2016 \A person's a person, no matter how small." Dr. Seuss UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Abstract Humanities Faculty School of Music Doctor of Philosophy The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: The life cycle of the child performer by Lyndsay Barnbrook The purpose of the research reported here is to explore the part played by children in musical theatre. It aims to do this on two levels. It presents, for the first time, an historical analysis of involvement of children in theatre from its earliest beginnings to the current date. It is clear from this analysis that the role children played in the evolution of theatre has been both substantial and influential, with evidence of a number of recurring themes. Children have invariably made strong contributions in terms of music, dance and spectacle, and have been especially prominent in musical comedy. Playwrights have exploited precocity for comedic purposes, innocence to deliver difficult political messages in a way that is deemed acceptable by theatre audiences, and youth, recognising the emotional leverage to be obtained by appealing to more primitive instincts, notably sentimentality and, more contentiously, prurience. Every age has had its child prodigies and it is they who tend to make the headlines. However the influence of educators and entrepreneurs, artistically and commercially, is often underestimated. Although figures such as Wescott, Henslowe and Harris have been recognised by historians, some of the more recent architects of musical theatre, like Noreen Bush, are largely unheard of outside the theatre community. -

Ruthless Empire (Royal Elite Book 6)

RUTHLESS EMPIRE ROYAL ELITE BOOK SIX RINA KENT Ruthless Empire Copyright © 2020 by Rina Kent All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise without written permission from the publisher. It is illegal to copy this book, post it to a website, or distribute it by any other means without permission, except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental. A L S O B Y R I N A K E N T ROYAL ELITE SERIES Cruel King Deviant King Steel Princess Twisted Kingdom Black Knight Vicious Prince Ruthless Empire LIES & TRUTHS DUET All The Lies All The Truths KINGDOM DUET Rule of a Kingdom (Free Prequel) Reign of a King Rise of a Queen TEAM ZERO SERIES Lured Crowed Ghosted Shadowed Misted Team Zero Boxset 1-3 THE RHODES SERIES Remorse (FREE) Ruin HATE & LOVE DUET He Hates Me He Hates Me Not To the divine, raw chaos inside you. A U T H O R N O T E Hello reader friend, Ruthless Empire marks the end of Royal Elite Series, and while there’s still an epilogue novella for all the characters, Cole and Silver’s book is the unofficial ending. Like you, this makes me so nostalgic and emotional. -

Effective Inhibition of Mrna Accumulation and Protein Expression of H5N1 Avian Influenza Virus NS1 Gene in Vitro by Small Interfering Rnas

Folia Microbiol (2013) 58:335–342 DOI 10.1007/s12223-012-0212-8 Effective inhibition of mRNA accumulation and protein expression of H5N1 avian influenza virus NS1 gene in vitro by small interfering RNAs Hanwei Jiao & Li Du & Yongchang Hao & Ying Cheng & Jing Luo & Wenhua Kuang & Donglin Zhang & Ming Lei & Xiaoxiao Jia & Xiaoru Zhang & Chao Qi & Hongxuan He & Fengyang Wang Received: 18 June 2012 /Accepted: 7 November 2012 /Published online: 29 November 2012 # Institute of Microbiology, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, v.v.i. 2012 Abstract Avian influenza has emerged as a devastating protein expressing HEK293 cell lines were established, four disease and may cross species barrier and adapt to a new small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting NS1 gene were host, causing enormous economic loss and great public designed, synthesized, and used to transfect the stable cell health threats, and non-structural protein 1 (NS1) is a mul- lines. Flow cytometry, real-time quantitative polymerase tifunctional non-structural protein of avian influenza virus chain reaction, and Western blot were performed to assess (AIV) that counters cellular antiviral activities and is a the expression level of NS1. The results suggested that virulence factor. RNA interference (RNAi) provides a pow- sequence-dependent specific siRNAs effectively inhibited erful promising approach to inhibit viral infection specifi- mRNA accumulation and protein expression of AIV NS1 cally. To explore the possibility of using RNAi as a strategy in vitro. These findings provide useful information for the against AIV infection, after the fusion protein expression development of RNAi-based prophylaxis and therapy for plasmids pNS1-enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), AIV infection. -

S 0620 State of Rhode Island

2017 -- S 0620 ======== LC002208 ======== STATE OF RHODE ISLAND IN GENERAL ASSEMBLY JANUARY SESSION, A.D. 2017 ____________ S E N A T E R E S O L U T I O N CONGRATULATING RHODE ISLAND NATIVE BILLY GILMAN ON HIS SINGING CAREER AND FINISHING AS RUNNER-UP ON THE VOICE Introduced By: Senators Morgan, Algiere, Kettle, Gee, and Paolino Date Introduced: March 16, 2017 Referred To: Recommended for Immediate Consideration 1 WHEREAS, William Wendell Gilman, III, known professionally as "Billy Gilman", was 2 born on May 24, 1988, in Westerly, Rhode Island, the son of Frances "Fran" Woodmansee and 3 William Wendell Gilman, Jr. Billy was raised in the Town of Richmond along with his younger 4 brother Colin; and 5 WHEREAS, Billy was a precocious youngster who loved singing from an early age. As a 6 toddler, Billy would sing for friends and family using his toy karaoke machine, wowing them 7 with his incredible voice and natural ability. By the age of 5, Billy would delight in shopping with 8 his mom at a Westerly supermarket, and would stick his head inside the door of a frozen food 9 case, and sing to see if the echo would make him sound like he was on a stage. He liked what he 10 heard and he scribbled on the condensation of the glass door the words, "Now Starring: Billy 11 Gilman!"; and 12 WHEREAS, Billy gave his first public performance on a stage at the age of seven. Billy 13 Gilman later performed at the Washington County Fair in Richmond and other local fairgrounds 14 in the New England area. -

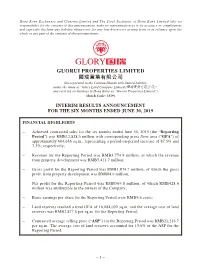

Guorui Properties Limited 國瑞置業有限公司

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. GUORUI PROPERTIES LIMITED 國瑞置業有限公司 (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability under the name of “Glory Land Company Limited (國瑞置業有限公司)” and carrying on business in Hong Kong as “Guorui Properties Limited”) (Stock Code: 2329) INTERIM RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT FOR THE SIX MONTHS ENDED JUNE 30, 2019 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS – Achieved contracted sales for the six months ended June 30, 2019 (the “Reporting Period”) was RMB12,828.3 million with corresponding gross floor area (“GFA”) of approximately 604,636 sq.m., representing a period-on-period increase of 87.5% and 7.3%, respectively; – Revenue for the Reporting Period was RMB3,774.9 million, of which the revenue from property development was RMB3,411.7 million; – Gross profit for the Reporting Period was RMB1,074.7 million, of which the gross profit from property development was RM804.6 million; – Net profit for the Reporting Period was RMB569.8 million, of which RMB428.6 million was attributable to the owners of the Company; – Basic earnings per share for the Reporting Period were RMB9.6 cents; – Land reserves reached a total GFA of 16,084,092 sq.m. and the average cost of land reserves was RMB2,877.8 per sq.m. for the Reporting Period; – Contracted average selling price (“ASP”) for the Reporting Period was RMB21,216.7 per sq.m. -

Haikou Is a Tropical Coastal City, Situated on the Northern Coast of Hainan, by the Mouth of the Nandu River

Haikou is a tropical coastal city, situated on the northern coast of Hainan, by the mouth of the Nandu River. The northern part of the city is Haidian Island, which is separated from the main part of Haikou by the Haidian River, a branch of the Nandu. Haikou was originally a port city. Today, it’s the capital of Hainan province and the most populous city in the province. The city covers 2,280 square kilometers and is home to around 2 million inhabitants. Haikou is on the northern edge of the torrid zone, and is part of the inter-tropical Convergence Zone. April to October is the active period for tropical storms and typhoons, most of which occur between August and September. May to October is the rainy season with the heaviest rainfall occurring in September. Despite its location, the city has a humid subtropical climate, falling just short of a tropical climate, with strong monsoonal influences. Nevertheless, the area has hot summers and warm winters, usually with high humidity. Extremes temperatures have ranged from 2.8 to 39.6 °C (37 to 103 °F) From June to October torrential rains may occur, with 7.0 days annually receiving at least 50 mm (1.97 in) of rain; this period accounts for nearly 70 percent of the annual rainfall of 1,650 mm (65 in). With monthly percentage of possible sunshine ranging from 31% in February to 61% in July, the city receives 2,070 hours of bright sunshine annually. Haikou is a transport hub with flights to many cities and boats to nearby mainland cities such as Beihai and Zhanjiang. -

Spire Light Spire Light

Spire Light Spire Light Spire Light A Journal of Creative Expression Andrew College 2021 2021 2 0 2 1 Spire Light: A Journal of Creative Expression Spire Light: A Journal of Creative Expression Andrew College 2021 Copyright © 2021 by Andrew College All rights reserved. This book or any portion may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review or scholarly journal. ISBN: 978-1-6780-6324-5 Andrew College 501 College Street Cuthbert, GA 39840 www.andrewcollege.edu/spire-light Cover Art: "Small Things," Chris Johnson Cover Design by Heather Bradley Editorial Staff Editor-in-Chief Penny Dearmin Art Editor Noah Varsalona Fiction Editors Kenyaly Quevedo Jermaine Glover Poetry Editor Hasani “Vibez” Comer Creative Nonfiction Editor Penny Dearmin Assistant Layout Editor Cameron Cabarrus www.andrewcollege.edu/spire-light Editor's Notes Penny Dearmin Editor-in-Chief To produce or curate art in this time is an act of service—to ourselves and the world who all need to believe again. We decided to say yes when there is a no at every corner. Yes, we will have our very first contest for the Illumination Prose Prize. Yes, we will accept an ekphrasis prose poem collaboration. Rather than place limits with a themed call for submissions, we did our best to remain open. These pieces should carry you to the hypothetical, a place where there are possibilities to unsee what you think you know. Isn’t that what we have done this year? Escaped? You can be grounded, too. -

New Studio on Broadway: Music Theatre and Acting

® ® 2019 CELEBRATING JIMMY NEDERLANDER James M. Nederlander or “Jimmy,” Chairman of The Nederlander Organization, was the visionary theatrical impresario who built one of the largest private live entertainment companies in the world known for producing and presenting world-class entertainment since 1912. Jimmy started working in the theatre at age 7 sweeping floors for his father, David Tobias (D.T.) Nederlander, in Detroit, Michigan. During a career that spanned over 70 years, Jimmy amassed a network of premier legitimate theatres including nine on Broadway: the Brooks Atkinson, Gershwin, Lunt-Fontanne, Marquis, Minskoff, Nederlander, Neil Simon, Richard Rodgers, and the world famous Palace; in Los Angeles: The Pantages; in London: the Adelphi, Aldwych, and Dominion; and in Chicago: the Auditorium, Broadway Playhouse, Cadillac Palace, and CIBC Theatres, and the Oriental Theatre which this year was renamed the James M. Nederlander Theatre in Jimmy’s honor. He produced over one hundred acclaimed Broadway musicals and plays including Annie, Applause, La Cage aux Folles, Les Liaisons Dangereuses, Me and My Girl, Nine, Noises Off, Peter Pan, Sweet Charity, The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickelby, The Will Rogers Follies, Woman of the Year, and many more. “Generous,” “loyal” and “trusted” are just a few of the accolades his friends use to describe him. Jimmy was beloved by the industry and the recipient of many distinguished honors including an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts from the University of Connecticut (2014), the Exploring the Arts Foundation Award (2014), the United Nations Foundation Champion Award (2012), The Broadway League’s Schoenfeld Vision for Arts Education Award (2011), the New York Pop’s Man of the Year (2008), and the special Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement (2004). -

A CHORUS LINE Teaching Resource.Pages

2016-2017 SEASON 2016-2017 SEASON Teacher Resource Guide and Lesson Plan Activities Featuring general information about our production along with some creative activities to Tickets: thalian.org help you make connections to your classroom curriculum before and after the show. 910-251-1788 The production and accompanying activities address North Carolina Essential Standards in Theatre or Arts, Goal A.1: Analyze literary texts & performances. CAC box office 910-341-7860 Look for this symbol for other curriculum connections. A Chorus Line Book, Music & Lyrics by: Jim Jacobs and Warren Casey April 28th - May 7th 7:30 PM Friday - Saturday and 3:00 PM Sunday Hannah Block Historic USO / Community Arts Center Second Street Stage 120 South 2nd Street (Corner of Orange) About this Teaching Resource Resource This Teaching Resource is designed to help build new partnerships that employ theatre and the arts. A major theme that runs through A Chorus Line, is the importance of education and Summary: the influence of teachers in the performers’ lives. In the 2006 Broadway production of A Page 2 Chorus Line, it was stated that the cast had spent, all together, 472 years in dance training with Summary, 637 teachers! The gypsies in A Chorus Line, are judged and graded, just as students are About the Musical, every day. Students know what it’s like to be “on the line.” This study guide for A Chorus Line, explores the Pulitzer Prize winning show in an interdisciplinary curriculum that takes in Vocabulary English/Language Arts, History/Social Studies, Music, Theatre, and Dance. Learning about Page 3 how A Chorus Line, was created will make viewing the show a richer experience for young Gypsies, Writing Prompts, people. -

Info Bulletin.Pmd

The East Asian Seas Congress 2006 The year 2003 created new opportunities for the sustainable development of the seas of East Asia, as it heralded the birth of the first-ever East Asian Seas Congress. The five-day event, held from 8-12 December in Putrajaya, Malaysia, brought together various stakeholders from diverse disciplines to work hand-in-hand to uphold the welfare of the East Asian Seas and ensure the sustainability of their resources. It will be remembered as the occasion where the Sustainable Development Strategy for the Seas of East Asia (SDS-SEA) was endorsed by environment- and ocean- related ministers and senior officials from PEMSEA’s 12 participating countries, with the signing of the Putrajaya Declaration. This Congress, a follow-up to the Putrajaya event, promises to drive the wheels of sustainable development in continuous motion, thereby bringing East Asia closer and closer to ultimately achieving a healthy and bountiful future for its seas and its people. Designed to address pressing coastal and marine environmental issues in practical formats and against a multidisciplinary setting, the various Congress components provide participants the opportunity to take active roles in sustainable development. Features The EAS Congress 2006 features the: • Ministerial Forum on the Implementation of the SDS-SEA* 14–15 December; • International Conference on Coastal and Ocean Governance: One Ocean, One People, One Vision 12–14 December; • Meeting of the EAS Partnership Council* 16 December; and • Youth Forum, Exhibits, Poster Sessions, Field Trip and other Side Events. *By invitation only. Host/Local Organizing Committee The 2006 Congress is being hosted by the government of PR China and co-organized by the State Oceanic Administration (SOA). -

Musical Theater Sheet

FACT MUSICAL THEATER SHEET Established by Congress in 1965, the National Endowment for the Arts is the independent federal agency whose funding and support gives Americans the opportunity to participate in the arts, exercise their imaginations, and develop their creative capacities. Through partnerships with state arts agencies, local leaders, other federal agencies, and the philanthropic sector, the Arts Endowment supports arts learning, affirms and celebrates America’s rich and diverse cultural heritage, and extends its work to promote equal access to the arts in every community across America. The National Endowment for the Arts is the only funder, public or private, to support the arts in all 50 states, U.S. territories, and the District of Columbia. The agency awards more than $120 million annually with each grant dollar matched by up to nine dollars from other funding sources. Economic Impact of the Arts The arts generate more money to local and state economies than several other industries. According to data released by the National Endowment for the Arts and the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, the arts and cultural industries contributed $804.2 billion to the U.S. economy in 2016, more than agriculture or transportation, and employed 5 million Americans. FUNDING THROUGH THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS MUSICAL THEATER PROGRAM: Fiscal Year 2018 marked the return of musical theater as its own discipline for grant award purposes. From 2014-2017, grants for musical theater were included in the theater discipline and prior to 1997, were awarded with opera as the opera/musical theater discipline. The numbers below, reflect musical theater grants awarded only when there was a distinct musical theater program. -

Evergrande Real Estate Group Limited 恒 大 地 產 集 團 有 限 公 司 (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 3333)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. Evergrande Real Estate Group Limited 恒 大 地 產 集 團 有 限 公 司 (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) (Stock Code: 3333) DISCLOSEABLE TRANSACTION The Board announces that on 2 December 2015, Shengyu (BVI) Limited, a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Company, as the purchaser, entered into three agreements respectively with the Vendor, pursuant to which the Purchaser agreed to acquire the interests in the relevant shares in and loans to the target companies held by the Vendor. These target companies hold the interests in the Haikou Project, the Huiyang Project and two projects located in Wuhan. Since the Vendor is the seller in these three agreements, such agreements will be aggregated in accordance with Rule 14.22 of the Listing Rules. As the applicable percentage ratios for the Acquisition exceed 5% but are less than 25%, the Acquisition constitutes a discloseable transaction for the Company under Chapter 14 of the Listing Rules and is subject to the reporting and announcement requirements under Chapter 14 of the Listing Rules. 1. INTRODUCTION The Board announces that on 2 December 2015, Shengyu (BVI) Limited, a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Company, as the purchaser, entered into three agreements respectively with the Vendor, pursuant to which the Purchaser agreed to acquire the interests in the relevant shares in and loans to the target companies held by the Vendor.