It Seems, Then, That in Light of the Range of Specific Definitions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dream of Morpheus: a Character Study of Narrative Power in Neil Gaiman’S the Sandman

– Centre for Languages and Literatur e English Studies The Dream of Morpheus: A Character Study of Narrative Power in Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman Astrid Dock ENGK01 Degree project in English Literature Autumn Term 2018 Centre for Languages and Literature Lund University Supervisor: Kiki Lindell Abstract This essay is primarily focused on the ambiguity surrounding Morpheus’ death in Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman. There is a divide in the character that is not reconciled within the comic: whether or not Morpheus is in control of the events that shape his death. Shakespeare scholars who have examined the series will have Morpheus in complete control of the narrative because of the similarities he shares with the character of Prospero. Yet the opposite argument, that Morpheus is a prisoner of Gaiman’s narrative, is enabled when he is compared to Milton’s Satan. There is sufficient evidence to support both readings. However, there is far too little material reconciling these two opposite interpretations of Morpheus’ character. The aim of this essay is therefore to discuss these narrative themes concerning Morpheus. Rather than Shakespeare’s Prospero and Milton’s Satan serving metonymic relationships with Morpheus, they should be respectively viewed as foils to further the ambiguous characterisation of the protagonist. With this reading, Morpheus becomes a character simultaneously devoid of, and personified by, narrative power. ii Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................... -

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Jonathan Berger, an Introduction to Nameless Love

For Immediate Release Contact: [email protected], 646-492- 4076 Jonathan Berger, An Introduction to Nameless Love In collaboration with Mady Schutzman, Emily Anderson, Tina Beebe, Julian Bittiner, Matthew Brannon, Barbara Fahs Charles, Brother Arnold Hadd, Erica Heilman, Esther Kaplan, Margaret Morton, Richard Ogust, Maria A. Prado, Robert Staples, Michael Stipe, Mark Utter, Michael Wiener, and Sara Workneh February 23 – April 5, 2020 Opening Sunday, February 23, noon–7pm From February 23 – April 5, 2020, PARTICIPANT INC is pleased to present Jonathan Berger, An Introduction to Nameless Love, co-commissioned and co-organized with the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard University. Taking the form of a large-scale sculptural installation that includes over 533,000 tin, nickel, and charcoal parts, Berger’s exhibition chronicles a series of remarkable relationships, creating a platform for complex stories about love to be told. The exhibition draws from Berger’s expansive practice, which comprises a spectrum of activity — brought together here for the first time — including experimental approaches to non-fiction, sculpture and installation, oral history and biography-based narratives, and exhibition-making practices. Inspired by a close friendship with fellow artist Ellen Cantor (1961-2013), An Introduction to Nameless Love charts a series of six extraordinary relationships, each built on a connection that lies outside the bounds of conventional romance. The exhibition is an examination of the profound intensity and depth of meaning most often associated with “true love,” but found instead through bonds based in work, friendship, religion, service, mentorship, community, and family — as well as between people and themselves, places, objects, and animals. -

741.5 Batman..The Joker

Darwyn Cooke Timm Paul Dini OF..THE FLASH..SUPERBOY Kaley BATMAN..THE JOKER 741.5 GREEN LANTERN..AND THE JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA! MARCH 2021 - NO. 52 PLUS...KITTENPLUS...DC TV VS. ON CONAN DVD Cuoco Bruce TImm MEANWHILE Marv Wolfman Steve Englehart Marv Wolfman Englehart Wolfman Marshall Rogers. Jim Aparo Dave Cockrum Matt Wagner The Comics & Graphic Novel Bulletin of In celebration of its eighty- queror to the Justice League plus year history, DC has of Detroit to the grim’n’gritty released a slew of compila- throwdowns of the last two tions covering their iconic decades, the Justice League characters in all their mani- has been through it. So has festations. 80 Years of the the Green Lantern, whether Fastest Man Alive focuses in the guise of Alan Scott, The company’s name was Na- on the career of that Flash Hal Jordan, Guy Gardner or the futuristic Legion of Super- tional Periodical Publications, whose 1958 debut began any of the thousands of other heroes and the contemporary but the readers knew it as DC. the Silver Age of Comics. members of the Green Lan- Teen Titans. There’s not one But it also includes stories tern Corps. Space opera, badly drawn story in this Cele- Named after its breakout title featuring his Golden Age streetwise relevance, emo- Detective Comics, DC created predecessor, whose appear- tional epics—all these and bration of 75 Years. Not many the American comics industry ance in “The Flash of Two more fill the pages of 80 villains become as iconic as when it introduced Superman Worlds” (right) initiated the Years of the Emerald Knight. -

PDF Download the Sandman Overture

THE SANDMAN OVERTURE: OVERTURE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK J. H. Williams, Neil Gaiman | 224 pages | 17 Nov 2015 | DC Comics | 9781401248963 | English | United States The Sandman Overture: Overture PDF Book Writer: Neil Gaiman Artist: J. The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. This would have been a better first issue. Nov 16, - So how do we walk the line of being a prequel, but still feeling relevant and fresh today on a visual level? Variant Covers. By continuing to use this website, you agree to their use. Click on the different category headings to find out more. Presented by MSI. Journeying into the realm of his sister Delirium , he learns that the cat was actually Desire in disguise. On an alien world, an aspect of Dream senses that something is very wrong, and dies in flames. Most relevant reviews. Williams III. The pair had never collaborated on a comic before "The Sandman: Overture," which tells the story immediately preceding the first issue of "The Sandman," collected in a book titled, "Preludes and Nocturnes. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. It's incredibly well written, but if you are looking for that feeling you had when you read the first issue of the original Sandman series, you won't find it here. Retrieved 13 March Logan's Run film adaptation TV adaptation. Notify me of new posts by email. Dreams, and by extension stories as we talked about in issue 1 , have meaning. Auction: New Other. You won't get that, not in these pages. -

Read Book the Sandman Vol. 5 Ebook

THE SANDMAN VOL. 5 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Neil Gaiman | 192 pages | 26 Sep 2011 | DC Comics | 9781401230432 | English | New York, NY, United States The Sandman Vol. 5 PDF Book The Sandman Vol. But after separating from her husband, she has ceased to dream and her fantasy kingdom has been savagely overrun by an evil entity known as the Cuckoo. Introduction secondary author all editions confirmed Klein, Todd Letterer secondary author all editions confirmed McKean, Dave Cover artist secondary author all editions confirmed Vozz, Danny Colorist secondary author all editions confirmed. Neil Gaiman To my wife Kathy, my pal Tim, and to everyone in jail. Sandman: Endless Nights - new edition. If you've yet to experience this exceptional epic, there have been five 30th Anniversary Edition volumes so far, all in stock. Sign in to Purchase Instantly. Uh… so where should I start? John Dee explains that he was once Doctor Destiny, and that he had been a scientist. In , Wanda is an important character. J'onn admits that the ruby Dream seeks is in storage since the satellite's destruction. Show More Show Less. Her neighbors task themselves to find her in the dream world, but it is a highly dangerous land between the living and the imaginary. Lucien [Sandman]. The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. We're here. Star Wars 30th Anniversary Trading Cards. Who that is I will not tell you, nor why they went away or what might happen if they ever returned. So fuck alllllllllll of that noise. -

Modern Mythopoeia &The Construction of Fictional Futures In

Modern Mythopoeia & The Construction of Fictional Futures in Design Figure 1. Cassandra. Anthony Fredrick Augustus Sandys. 1904 2 Modern Mythopoeia & the Construction of Fictional Futures in Design Diana Simpson Hernandez MA Design Products Royal College of Art October 2012 Word Count: 10,459 3 INTRODUCTION: ON MYTH 10 SLEEPWALKERS 22 A PRECOG DREAM? 34 CONCLUSION: THE SLEEPER HAS AWAKEN 45 APPENDIX 77 BIBLIOGRAPHY 90 4 Figure 1. Cassandra. Anthony Fredrick Augustus Sandys. 1904. Available from: <http://culturepotion.blogspot.co.uk/2010/08/witches- and-witchcraft-in-art-history.html> [accessed 30 July 2012] Figure 2. Evidence Dolls. Dunne and Raby. 2005. Available from: <http://www.dunneandraby.co.uk/content/projects/69/0> [accessed 30 July 2012] Figure 3. Slave City-cradle to cradle. Atelier Van Lieshout. 2009. Available from: <http://www.designboom.com/weblog/cat/8/view/7862/atelier-van- lieshout-slave-city-cradle-to-cradle.html> [accessed 30 July 2012] Figure 4. Der Jude. 1943. Hans Schweitzer. Available from: <http://www.calvin.edu/academic/cas/gpa/posters2.htm> [accessed 15 September 2012] Figure 5. Lascaux cave painting depicting the Seven Sisters constellation. Available from: <http://madamepickwickartblog.com/2011/05/lascaux- and-intimate-with-the-godsbackstage-pass-only/> [accessed 05 July 2012] Figure 6. Map Presbiteri Johannis, Sive, Abissinorum Imperii Descriptio by Ortelius. Antwerp, 1573. Available from: <http://www.raremaps.com/gallery/detail/9021?view=print > [accessed 30 May 2012] 5 Figure 7. Mercator projection of the world between 82°S and 82°N. Available from: <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mercator_projection> [accessed 05 July 2012] Figure 8. The Gall-Peters projection of the world map Available from: <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gall–Peters_projection> [accessed 05 July 2012] Figure 9. -

The Sand-Man by Ernst T.A

1 The Sand-Man By Ernst T.A. Hoffmann Translated by J.Y. Bealby, B.A. Formerly Scholar of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge Charles Scribner's Sons, New York, 1885 Nathanael to Lothair I KNOW you are all very uneasy because I have not written for such a long, long time. Mother, to be sure, is angry, and Clara, I dare say, believes I am living here in riot and revelry, and quite forgetting my sweet angel, whose image is so deeply engraved upon my heart and mind. But that is not so; daily and hourly do I think of you all, and my lovely Clara's form comes to gladden me in my dreams, and smiles upon me with her bright eyes, as graciously as she used to do in the days when I went in and out amongst you. Oh! how could I write to you in the distracted state of mind in which I have been, and which, until now, has quite bewildered me! A terrible thing has happened to me. Dark forebodings of some awful fate threatening me are spreading themselves out over my head like black clouds, impenetrable to every friendly ray of sunlight. I must now tell you what has taken place; I must, that I see well enough, but only to think upon it makes the wild laughter burst from my lips. Oh! my dear, dear Lothair, what shall I say to make you feel, if only in an inadequate way, that that which happened to me a few days ago could thus really exercise such a hostile and disturbing influence upon my life? Oh that you were here to see for yourself! but now you will, I suppose, take me for a superstitious ghost-seer. -

Llistat Còmics Descatalogats.Xml

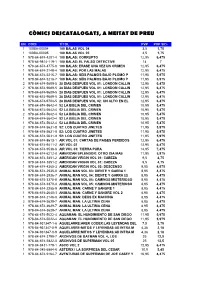

CÒMICS DESCATALOGATS, A MEITAT DE PREU UN. CODI TÍTOL PVP PVP 50% 1 100BA-00004 100 BALAS VOL 04 3,5 1,75 1 100BA-00005 100 BALAS VOL 05 3,5 1,75 1 978-84-674-4201-4 100 BALAS: CORRUPTO 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-9814-119-1 100 BALAS: EL FALSO DETECTIVE 14 7 1 978-84-674-4775-0 100 BALAS: ERASE UNA VEZ UN CRIMEN 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-2148-4 100 BALAS: POR LAS MALAS 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-5216-7 100 BALAS: SEIS PALMOS BAJO PLOMO P 11,95 5,975 1 978-84-674-5216-7 100 BALAS: SEIS PALMOS BAJO PLOMO P 11,95 5,975 2 978-84-674-9689-5 28 DIAS DESPUES VOL 01: LONDON CALLIN 12,95 6,475 2 978-84-674-9689-5 28 DIAS DESPUES VOL 01: LONDON CALLIN 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-9689-5 28 DIAS DESPUES VOL 01: LONDON CALLIN 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-9689-5 28 DIAS DESPUES VOL 01: LONDON CALLIN 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-9704-5 28 DIAS DESPUES VOL 02: UN ALTO EN EL 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-5642-4 52 LA BIBLIA DEL CRIMEN 10,95 5,475 5 978-84-674-5642-4 52 LA BIBLIA DEL CRIMEN 10,95 5,475 2 978-84-674-5642-4 52 LA BIBLIA DEL CRIMEN 10,95 5,475 1 978-84-674-5642-4 52 LA BIBLIA DEL CRIMEN 10,95 5,475 1 978-84-674-5642-4 52 LA BIBLIA DEL CRIMEN 10,95 5,475 2 978-84-674-5631-8 52: LOS CUATRO JINETES 11,95 5,975 1 978-84-674-5631-8 52: LOS CUATRO JINETES 11,95 5,975 3 978-84-674-5631-8 52: LOS CUATRO JINETES 11,95 5,975 1 978-84-674-8613-1 AIR VOL 01: CARTAS DE PAISES PERDIDOS 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-9411-2 AIR VOL 02 12,95 6,475 1 978-84-674-9538-6 AIR VOL 03: TIERRA PURA 14,95 7,475 1 978-84-674-6212-8 AMERICAN SPLENDOR: OTRO DIA MAS 11,95 5,975 1 978-84-674-3851-2 -

ARCHIE COMICS Random House Adult Blue Omni, Summer 2012

ARCHIE COMICS Random House Adult Blue Omni, Summer 2012 Archie Comics Archie Meets KISS Summary: A highly unexpected pairing leads to a very Alex Segura, Dan Parent fun title that everyone’s talking about. Designed for both 9781936975044 KISS’s and Archie’s legions of fans and backed by Pub Date: 5/1/12 (US, Can.), On Sale Date: 5/1 massive publicity including promotion involving KISS $12.99/$14.99 Can. cofounders Gene Simmons and Paul Stanley, Archie 112 pages expects this title to be a breakout success. Paperback / softback / Trade paperback (US) Comics & Graphic Novels / Fantasy From the the company that’s sold over 1 billion comic books Ctn Qty: 0 and the band that’s sold over 100 million albums and DVDs 0.8lb Wt comes this monumental crossover hit! Immortal rock icons 363g Wt KISS join forces ... Author Bio: Alex Segura is a comic book writer, novelist and musician. Alex has worked in comics for over a decade. Before coming to Archie, Alex served as Publicity Manager at DC Comics. Alex has also worked at Wizard Magazine, The Miami Herald, Newsarama.com and various other outlets and websites. Author Residence: New York, NY Random House Adult Blue Omni, Summer 2012 Archie Comics Archie Meets KISS: Collector's Edition Summary: A highly unexpected pairing leads to a very Alex Segura, Dan Parent, Gene Simmons fun title that everyone’s talking about. Designed for both 9781936975143 KISS’s and Archie’s legions of fans and backed by Pub Date: 5/1/12 (US, Can.), On Sale Date: 5/1 massive publicity including promotion involving KISS $29.99/$34.00 Can. -

Sandman, Aesthetics and Canonisation Today I Want To

Sandman, Aesthetics and Canonisation Today I want to examine the ways in which Neil Gaiman’s Sandman has used narrative, format and aesthetic to move ever closer to the notion of the literary text. Particularly going to consider how it exploits the author function and enacts the struggle for cultural worth that comics seem consistently engaged in. Sandman is an epic series rewriting a golden-age superhero into an immortal deity. It is best remembered for its mythological content and literary references, and these elements have allowed it to claim its place as a canonised graphic novel (despite not actually being a singular GN but a maxi-series across multiple trade paperbacks!). Neil Gaiman’s authorship and authority dominate the text and epitomise Michel Foucault’s author function. But Sandman also draws heavily on mixed media and artistic variation and these aspects are less often discussed. Far from supporting a singular author function, Sandman’s visual style is multiple and varied. But despite this, in paratexts the artistic contributions are frequently subsumed into Gaiman’s authorship. However, a closer reading demonstrates that in fact this artistic variety destabilises clear-cut authorship and enacts the particular status struggles of comics as a collaborative medium struggling against the graphic novel branding. SLIDE: literary pix Sandman was launched in 1989 and became the flagship title for DC’s new Vertigo imprint. Vertigo’s publications contributed heavily to the mainstream cultural revaluation of comics as graphic novels, and critics such as Candace West have argued that Sandman in particular was instrumental here due to the attention the series received from mainstream media such as Rolling Stone magazine. -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items DC COLLECTING THE MULTIVERSE On our Cover The Art of Sideshow By Andrew Farago. Recommended. MASTERPIECES OF FANTASY ART Delve into DC Comics figures and Our Highest Recom- sculptures with this deluxe book, mendation. By Dian which features insights from legendary Hanson. Art by Frazetta, artists and eye-popping photography. Boris, Whelan, Jones, Sideshow is world famous for bringing Hildebrandt, Giger, DC Comics characters to life through Whelan, Matthews et remarkably realistic figures and highly al. This monster-sized expressive sculptures. From Batman and Wonder Woman to The tome features original Joker and Harley Quinn...key artists tell the story behind each paintings, contextualized extraordinary piece, revealing the design decisions and expert by preparatory sketches, sculpting required to make the DC multiverse--from comics, film, sculptures, calen- television, video games, and beyond--into a reality. dars, magazines, and Insight Editions, 2020. paperback books for an DCCOLMSH. HC, 10x12, 296pg, FC $75.00 $65.00 immersive dive into this SIDESHOW FINE ART PRINTS Vol 1 dynamic, fanciful genre. Highly Recommened. By Matthew K. Insightful bios go beyond Manning. Afterword by Tom Gilliland. Wikipedia to give a more Working with top artists such as Alex Ross, accurate and eye-opening Olivia, Paolo Rivera, Adi Granov, Stanley look into the life of each “Artgerm” Lau, and four others, Sideshow artist. Complete with fold- has developed a series of beautifully crafted outs and tipped-in chapter prints based on films, comics, TV, and ani- openers, this collection will mation. These officially licensed illustrations reign as the most exquisite are inspired by countless fan-favorite prop- and informative guide to erties, including everything from Marvel and this popular subject for DC heroes and heroines and Star Wars, to iconic classics like years to come.