Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master Interview Was Provided by the National Endowment for the Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Top Attractions

LOS ANGELES L.A. LIVE 901 West Olympic Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90015 COURTYARD | 213.443.9222 | Marriott.com.com/LAXLD RESIDENCE INN | 213.443.9200 | Marriott.com/LAXRI 5 ATTRACTIONS 34 1 Arts District (2.8 mi) BURBANK 2 Bunker Hill (1.3 mi) 3 Chinatown (2.8 mi) 4 Dodger Stadium 5 Dolby Theater (7.5 mi) 18 101 6 Financial District (0.7 mi) PASADENA 7 Griffith210 Observatory/LA Zoo (8.3 mi) 8 Hollywood Bowl (8.3mi) 22 9 LACMA (6.2 mi) 10 LA LIVE (1 minute walk) 101 STAPLEs Center (less than 5 minute walk) Microsoft Theater (less than 5 minute walk) 7 11 Grammy Museum (less than 5 minute walk) 12 Little Tokyo (2.8 mi) 21 13 Los Angeles Coliseum/LA Rams Stadium (3 mi) 14 Los Angeles Convention Center (0.7 mi, 14 minute walk) 8 Los Angeles Music Center (1.8 mi) HOLLYWOOD 2. BUNKER HILL Dorothy Chandler Pavilion (1.8 mi) 25 32 5 3. CHINATOWN Ahmanson Theater (1.8 mi) 5 6. FINANCIAL DISTRICT Mark Taper Forum (1.8 mi) BEVERLY HILLS 12. LITTLE TOKYO Walt Disney Concert Hall (1.8 mi) 17. OLIVERA STREET 15 Los Angeles Public Library (0.9 mi) 4 28. GRAND CENTRAL 10 30. THE BLOC/MACY’S 16 OUE Skyspace LA (1.1 mi) 9 3 35. 7TH ST/METRO CENTER STATION 17 Olivera Street (2.6 mi) 36 36. UNION STATION 18 Rose Bowl Stadium (11.5 mi) 20 17 28 19 Santa Monica Pier (15.2 mi) 6 30 12 20 The Broad (1.6 mi) 21 16 35 2 27 The Getty (14.7 mi) 22 Universal Studios Hollywood/Universal60 City Walk (10 mi) 10 L.A. -

CATALOGUE WELCOME to NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS and NAXOS NOSTALGIA, Twin Compendiums Presenting the Best in Vintage Popular Music

NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS/NOSTALGIA CATALOGUE WELCOME TO NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS AND NAXOS NOSTALGIA, twin compendiums presenting the best in vintage popular music. Following in the footsteps of Naxos Historical, with its wealth of classical recordings from the golden age of the gramophone, these two upbeat labels put the stars of yesteryear back into the spotlight through glorious new restorations that capture their true essence as never before. NAXOS JAZZ LEGENDS documents the most vibrant period in the history of jazz, from the swinging ’20s to the innovative ’40s. Boasting a formidable roster of artists who forever changed the face of jazz, Naxos Jazz Legends focuses on the true giants of jazz, from the fathers of the early styles, to the queens of jazz vocalists and the great innovators of the 1940s and 1950s. NAXOS NOSTALGIA presents a similarly stunning line-up of all-time greats from the golden age of popular entertainment. Featuring the biggest stars of stage and screen performing some of the best- loved hits from the first half of the 20th century, this is a real treasure trove for fans to explore. RESTORING THE STARS OF THE PAST TO THEIR FORMER GLORY, by transforming old 78 rpm recordings into bright-sounding CDs, is an intricate task performed for Naxos by leading specialist producer-engineers using state-of-the-art-equipment. With vast personal collections at their disposal, as well as access to private and institutional libraries, they ensure that only the best available resources are used. The records are first cleaned using special equipment, carefully centred on a heavy-duty turntable, checked for the correct playing speed (often not 78 rpm), then played with the appropriate size of precision stylus. -

Elyssa Pennell: Okay

Elyssa Pennell: Okay. So, it is November 20 and we’re in Glickman Library in Portland, Maine and I am the student researcher. My name is Elyssa Pennell. E-L-Y-S-S-A P-E-N-N-E-L-L and would please say your name and spell it for me? Marvin Ellison: Be glad to, so I’m Marvin Ellison. E-L-L-I-S-O-N and Marvin with a V. And we're off and running. Elyssa: Yes. Okay, so you can refuse to answer any question at any time and you can end the interview at any point. Marvin: Great. You know the teacher’s trick though? You get asked a question and you answer not the question that is asked, but the question you would like to be asked. Elyssa: Yes, also the politician’s trick too. Marvin: Exactly. Elyssa: Yes. Marvin: So be forewarned. Elyssa: Okay. Marvin: Keep me on track. Elyssa: Alright so do you want to start with where you were born? How you grew up? At all? Marvin: Sure, I’d be glad to. Elyssa: Okay. Marvin: So I grew up in the South, I grew up in Knoxville, Tennessee and I grew up as a person of faith in the Presbyterian Church US, which is the Southern branch of the Presbyterian Church and went to Davidson College in North Carolina for my undergraduate work and then after graduating from college I moved to Chicago for graduate school and then to New York for another a graduate program and eventually came to Maine and finished my doctoral program and was given a job in Bangor theological seminary. -

The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER , President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 4, 2016, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters GARY BURTON WENDY OXENHORN PHAROAH SANDERS ARCHIE SHEPP Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center’s Artistic Director for Jazz. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 2 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, pianist and Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, chairman of the NEA DEBORAH F. RUTTER, president of the Kennedy Center THE 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS Performances by NEA JAZZ MASTERS: CHICK COREA, piano JIMMY HEATH, saxophone RANDY WESTON, piano SPECIAL GUESTS AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE, trumpeter LAKECIA BENJAMIN, saxophonist BILLY HARPER, saxophonist STEFON HARRIS, vibraphonist JUSTIN KAUFLIN, pianist RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA, saxophonist PEDRITO MARTINEZ, percussionist JASON MORAN, pianist DAVID MURRAY, saxophonist LINDA OH, bassist KARRIEM RIGGINS, drummer and DJ ROSWELL RUDD, trombonist CATHERINE RUSSELL, vocalist 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS -

J2P and P2J Ver 1

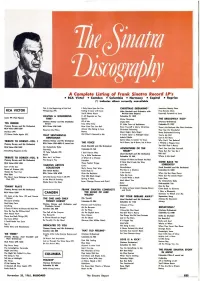

inulTo discography A Complete Listing of Frank Sinatra Record LP's RCA Victor Camden Columbia Harmony Capitol Reprise ( *) indicates album currently unavailable Is This the Beginning of the End I Only Have Eyes for You CHRISTMAS DREAMING* American Beauty Rose Whispering RCA VICTOR (PP) Falling in Love with Love (Alex Stordahl and Orchestra with Five Minutes More You'll Never Know the Kea Lane Singers) Farewell, Farewell to Love HAVING A WONDERFUL It All Depends on You Columbia CL 1032 (note: PP -Pied Pipers) TIME* Spasm' White Christmas THE BROADWAY KICK* (Tommy Dorsey and His Clambake All of Me Jingle Bells (Various Orchestras) YES INDEED Seven) Time After Time O' Little Town of Bethlehem Columbia CL 1297 (Tommy Dorsey and His Orchestra) RCA Victor LPM 1643 How Cute Can You Be? Have Yourself a Merry Christmas There's No Business Like Show Business RCA Victor LPM 1229 Almost Like Being in Love Head on My Pillow Christmas Dreaming They Say It's Wonderful Stardust (PP) Nancy Silent Night, Holy Night Some Enchanted Evening I'll Never Smile Ohl What It Seemed to Me Again (PP) THAT SENTIMENTAL It Come Upon a Midnight Clear You're My Girl GENTLEMAN Adeste Fideles Lost in the Stars Santa Clous Is Conlin' to Town (Tommy Dorsey and His Orchestra) Can't You Behave? TRIBUTE TO DORSEY -VOL. 1 Let It Snow, let It RCA Victor LPM THE VOICE Snow, Let It Snow I Whistle a Happy Tune (Tommy Dorsey and His Orchestra) 6003 -2 record set (Axel Stordahl and His Orchestra) The Girl That I Marry RCA Victor LPM 1432 My Melancholy Baby ADVENTURES THE Can't You Just See Yourself Yearning Columbia CL 743 OF Everything Happens to Me HEART* There But For You Go I l'll Take Tallulah (PP) I Don't Know Why (Axel Stordahl and His Orchestra) Boli Ha'i Marie Try a Little Tenderness Columbia CL 953 Where Is My Bess? How Am Know TRIBUTE TO DORSEY -VOL. -

The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBoRAh F. RUTTER, President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 16, 2018, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters TODD BARKAN JOANNE BRACKEEN PAT METHENY DIANNE REEVES Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz. This performance will be livestreamed online, and will be broadcast on Sirius XM Satellite Radio and WPFW 89.3 FM. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 2 THE 2018 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts DEBORAH F. RUTTER, President of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts The 2018 NEA JAzz MASTERS Performances by NEA Jazz Master Eddie Palmieri and the Eddie Palmieri Sextet John Benitez Camilo Molina-Gaetán Jonathan Powell Ivan Renta Vicente “Little Johnny” Rivero Terri Lyne Carrington Nir Felder Sullivan Fortner James Francies Pasquale Grasso Gilad Hekselman Angélique Kidjo Christian McBride Camila Meza Cécile McLorin Salvant Antonio Sanchez Helen Sung Dan Wilson 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 -

The History and Development of Jazz Piano : a New Perspective for Educators

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1975 The history and development of jazz piano : a new perspective for educators. Billy Taylor University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Taylor, Billy, "The history and development of jazz piano : a new perspective for educators." (1975). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 3017. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/3017 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. / DATE DUE .1111 i UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS LIBRARY LD 3234 ^/'267 1975 T247 THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS A Dissertation Presented By William E. Taylor Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfil Iment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF EDUCATION August 1975 Education in the Arts and Humanities (c) wnii aJ' THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO: A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS A Dissertation By William E. Taylor Approved as to style and content by: Dr. Mary H. Beaven, Chairperson of Committee Dr, Frederick Till is. Member Dr. Roland Wiggins, Member Dr. Louis Fischer, Acting Dean School of Education August 1975 . ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO; A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS (AUGUST 1975) William E. Taylor, B.S. Virginia State College Directed by: Dr. -

By Messenger and E-Mail

Victor De la Cruz || 1^1 Iclll Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, LLP manatt | phelps | phillips Direct Dial. (310)312-4305 E-mail: [email protected] October 21, 2014 Client-Matter: 45860-031 BY MESSENGER AND E-MAIL President Patsaouras and Honorable Commissioners Board of Recreation and Parks Commissioners City of Los Angeles 221 N. Figueroa Street, Room 1510 Los Angeles, CA 90012 Re: The Greek Theatre Concession Award - Response to Mayer Brown Letters of October 8, 2014 and October 20, 2014 Dear President Patsaouras and Honorable Commissioners: On behalf of Live Nation Worldwide, Inc. ("Live Nation"), we write in response to the October 8, 2014 and October 20, 2014 letters from Nederlander-AEG's legal counsel. Unfortunately, these letters are nothing more than additional attempts to confuse and delay the process after your staff and a five person independent panel of experts (the "Evaluation Panel") unanimously found that Live Nation by far delivered the superior proposal to operate the Greek Theatre for the next 20 years. Live Nation scored a total of 455 points out of a possible 500, whereas Nederlander-AEG only scored 396. Live Nation delivered a vastly superior proposal - it is that simple. This letter will demonstrate, and even the most cursory review of the two proposals will confirm, that Nederlander-AEG's proposal - like Nederlander's current operation of the Greek Theatre - leaves much to be desired. Whether it's the Nederlander-AEG proposal's inappropriate use of Patina Group venue photographs (Patina Group is not Nederlander's, but Live Nation's food and beverage partner), a capital improvement contribution that isn't even half of Live Nation's, or a misleading pro forma projecting revenue from up to 80 shows when the proposal guarantees 50 shows elsewhere, the 40-year incumbent's proposal was so flawed that it could only have come from a company with a self-entitled belief that it, and not the people of Los Angeles, own the Greek Theatre. -

Composers' Bridge!

Composers’ Bridge Workbook Contents Notation Orchestration Graphic notation 4 Orchestral families 43 My graphic notation 8 Winds 45 Clefs 9 Brass 50 Percussion 53 Note lengths Strings 54 Musical equations 10 String instrument special techniques 59 Rhythm Voice: text setting 61 My rhythm 12 Voice: timbre 67 Rhythmic dictation 13 Tips for writing for voice 68 Record a rhythm and notate it 15 Ideas for instruments 70 Rhythm salad 16 Discovering instruments Rhythm fun 17 from around the world 71 Pitch Articulation and dynamics Pitch-shape game 19 Articulation 72 Name the pitches – part one 20 Dynamics 73 Name the pitches – part two 21 Score reading Accidentals Muddling through your music 74 Piano key activity 22 Accidental practice 24 Making scores and parts Enharmonics 25 The score 78 Parts 78 Intervals Common notational errors Fantasy intervals 26 and how to catch them 79 Natural half steps 27 Program notes 80 Interval number 28 Score template 82 Interval quality 29 Interval quality identification 30 Form Interval quality practice 32 Form analysis 84 Melody Rehearsal and concert My melody 33 Presenting your music in front Emotion melodies 34 of an audience 85 Listening to melodies 36 Working with performers 87 Variation and development Using the computer Things you can do with a Computer notation: Noteflight 89 musical idea 37 Sound exploration Harmony My favorite sounds 92 Harmony basics 39 Music in words and sentences 93 Ear fantasy 40 Word painting 95 Found sound improvisation 96 Counterpoint Found sound composition 97 This way and that 41 Listening journal 98 Chord game 42 Glossary 99 Welcome Dear Student and family Welcome to the Composers' Bridge! The fact that you are being given this book means that we already value you as a composer and a creative artist-in-training. -

Instead Draws Upon a Much More Generic Sort of Free-Jazz Tenor

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. BILL HOLMAN NEA Jazz Master (2010) Interviewee: Bill Holman (May 21, 1927 - ) Interviewer: Anthony Brown with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: February 18-19, 2010 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 84 pp. Brown: Today is Thursday, February 18th, 2010, and this is the Smithsonian Institution National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters Oral History Program interview with Bill Holman in his house in Los Angeles, California. Good afternoon, Bill, accompanied by his wife, Nancy. This interview is conducted by Anthony Brown with Ken Kimery. Bill, if we could start with you stating your full name, your birth date, and where you were born. Holman: My full name is Willis Leonard Holman. I was born in Olive, California, May 21st, 1927. Brown: Where exactly is Olive, California? Holman: Strange you should ask [laughs]. Now it‟s a part of Orange, California. You may not know where Orange is either. Orange is near Santa Ana, which is the county seat of Orange County, California. I don‟t know if Olive was a part of Orange at the time, or whether Orange has just grown up around it, or what. But it‟s located in the city of Orange, although I think it‟s a separate municipality. Anyway, it was a really small town. I always say there was a couple of orange-packing houses and a railroad spur. Probably more than that, but not a whole lot.