Funnyman: the Tragic Adventures of a Crime-Fighting Comedian by Paul Hirsch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Premiere Props • Hollyw Ood a Uction Extra Vaganza VII • Sep Tember 1 5

Premiere Props • Hollywood Auction Extravaganza VII • September 15-16, 2012 • Hollywood Live Auctions Welcome to the Hollywood Live Auction Extravaganza weekend. We have assembled a vast collection of incredible movie props and costumes from Hollywood classics to contemporary favorites. From an exclusive Elvis Presley museum collection featured at the Mississippi Music Hall Of Fame, an amazing Harry Potter prop collection featuring Harry Potter’s training broom and Golden Snitch, to a entire Michael Jackson collection featuring his stage worn black shoes, fedoras and personally signed items. Plus costumes and props from Back To The Future, a life size custom Robby The Robot, Jim Carrey’s iconic mask from The Mask, plus hundreds of the most detailed props and costumes from the Underworld franchise! We are very excited to bring you over 1,000 items of some of the most rare and valuable memorabilia to add to your collection. Be sure to see the original WOPR computer from MGM’s War Games, a collection of Star Wars life size figures from Lucas Film and Master Replicas and custom designed costumes from Bette Midler, Kate Winslet, Lily Tomlin, and Billy Joel. If you are new to our live auction events and would like to participate, please register online at HollywoodLiveAuctions.com to watch and bid live. If you would prefer to be a phone bidder and be assisted by one of our staff members, please call us to register at (866) 761-7767. We hope you enjoy the Hollywood Live Auction Extravaganza V II live event and we look forward to seeing you on October 13-14 for Fangoria’s Annual Horror Movie Prop Live Auction. -

The BG News April 20, 1990

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 4-20-1990 The BG News April 20, 1990 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News April 20, 1990" (1990). BG News (Student Newspaper). 5076. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/5076 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. ARTS IN APRIL BG NETTERS VICTORIOUS International and ethnic Falcons prevail 6-3 artworks presented Friday Mag ^ over tough Wooster club Sports The Nation *s Best College Newspaper Friday Weather Vol.72 Issue 116 April 20,1990 Bowling Green, Ohio High 67* The BG News Low 49° BRIEFLY Hostage release postponed Erosion In Damascus. Syrian Foreign Minis- by Rodeina Kenaan "The United States ter Farouk al-Sharaa said his govern- Associated Press writer ment has "been exerting a great deal of of ozone CAMPUS does not knuckle under influence" to secure the hostage BEIRUT, Lebanon — Pro-Iranian to demands." release by Sunday. He would not elab- Beta rescheduled: The 27th kidnappers said Thursday they post- -George Bush, orate. layers annual Beta 500 race has been poned indefinitely the release of an President Bush said the United rescheduled for this Sunday at noon. American hostage because the United CJ.S. -

Katie Wackett Honours Final Draft to Publish (FILM).Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Female Subjectivity, Film Form, and Weimar Aesthetics: The Noir Films of Robert Siodmak by Kathleen Natasha Wackett A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ARTS IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BA HONOURS IN FILM STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION, MEDIA, AND FILM CALGARY, ALBERTA APRIL, 2017 © Kathleen Natasha Wackett 2017 Abstract This thesis concerns the way complex female perspectives are realized through the 1940s noir films of director Robert Siodmak, a factor that has been largely overseen in existing literature on his work. My thesis analyzes the presentation of female characters in Phantom Lady, The Spiral Staircase, and The Killers, reading them as a re-articulation of the Weimar New Woman through the vernacular of Hollywood cinema. These films provide a representation of female subjectivity that is intrinsically connected to film as a medium, as they deploy specific cinematic techniques and artistic influences to communicate a female viewpoint. I argue Siodmak’s iterations of German Expressionist aesthetics gives way to a feminized reading of this style, communicating the inner, subjective experience of a female character in a visual manner. ii Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without my supervisor Dr. Lee Carruthers, whose boundless guidance and enthusiasm is not only the reason I love film noir but why I am in film studies in the first place. I’d like to extend this grateful appreciation to Dr. Charles Tepperman, for his generous co-supervision and assistance in finishing this thesis, and committee member Dr. Murray Leeder for taking the time to engage with my project. -

October 2011 Newsletter.Pub

Community Board # 4 315 Wyckoff Avenue, 2nd Fl., Brooklyn, NY 11237 Tel.#: (718) 628-8400 / Fax #: (718) 628-8619 Email: [email protected] Monthly Community Board # 4 Meeting Hope Gardens Multi-Service Center 195 Linden Street (Corner of Wilson Avenue), Brooklyn, NY 11237 Wednesday, October 19, 2011 at 6:00 PM Public Hearing Item(s) 1. MTA-NEW YORK CITY TRANSIT-Station renewals on M-Line Central Avenue & Knickerbocker Avenue. Regular Board Meeting Agenda: 1. First Roll Call 7. Recommendations 2. Acceptance of Agenda 8. Old Business 3. Acceptance of Previous Meeting’s Minutes 9. New Business 4. Chairperson’s Report 10. Announcements (1.5 minutes only) Introduction of Elected Officials (Representative) 11. Second Roll Call 5. District Manger’s Report 12. Adjournment 6. Committee Reports: • Environmental/Transportation-Eliseo Ruiz • Health/Hospital & Human Services-Mary McClellan • Housing Land-Use-Martha Brown • Public Safety-Barbara Smith • Youth & Education-Virgie Jones 83rd Precinct Community Council Meeting The Next CEC 32 Meeting Tuesday, October 18, 2011 Thursday, October 20, 2011 480 Knickerbocker Avenue P.S. 299 corner Bleecker Street 88 Woodbine Street (Muster Room—6:30PM) (Bet. Bushwick & Evergreen Aves.) Featuring: “Domestic Violence Presentation” 6:00 PM-Working Session / 7:00 PM-Public Sessions Brooklyn Parks Commissioner and Community Board #4 Looking for Parks Stewards (VOLUNTEERS FOR) Maria Hernandez Park, Irving Square Park, Bushwick Playground, Green/Central/Noll These Volunteer Stewards will be part of a brand new community program designed to assist in the maintenance of NYC Parks & Playgrounds. Looming City budget cuts will ultimately affect the manpower responsible for cleaning and maintaining local parks and playgrounds. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

Merchants Of

Introduction The Jews never faced much anti-Semitism in America. This is due, in large part, to the underlying ideologies it was founded on; namely, universalistic interpretations of Christianity and Enlightenment ideals of freedom, equality and opportunity for all. These principles, which were arguably created with noble intent – and based on the values inherent in a society of European-descended peoples of high moral character – crippled the defenses of the individualistic-minded White natives and gave the Jews free reign to consolidate power at a rather alarming rate, virtually unchecked. The Jews began emigrating to the United States in waves around 1880, when their population was only about 250,000. Within a decade that number was nearly double, and by the 1930s it had shot to 3 to 4 million. Many of these immigrants – if not most – were Eastern European Jews of the nastiest sort, and they immediately became vastly overrepresented among criminals and subversives. A 1908 police commissioner report shows that while the Jews made up only a quarter of the population of New York City at that time, they were responsible for 50% of its crime. Land of the free. One of their more common criminal activities has always been the sale and promotion of pornography and smut. Two quotes should suffice in backing up this assertion, one from an anti-Semite, and one from a Jew. Firstly, an early opponent of the Jews in America, Greek scholar T.T. Timayenis, wrote in his 1888 book The Original Mr. Jacobs that nearly “all obscene publications are the work of the Jews,” and that the historian of the future who shall attempt to describe the catalogue of the filthy publications issued by the Jews during the last ten years will scarcely believe the evidence of his own eyes. -

“Justice League Detroit”!

THE RETRO COMICS EXPERIENCE! t 201 2 A ugus o.58 N . 9 5 $ 8 . d e v r e s e R s t h ® g i R l l A . s c i m o C C IN THE BRONZE AGE! D © & THE SATELLITE YEARS M T a c i r e INJUSTICE GANG m A f o e MARVEL’s JLA, u g a e L SQUADRON SUPREME e c i t s u J UNOFFICIAL JLA/AVENGERS CROSSOVERS 7 A SALUTE TO DICK DILLIN 0 8 2 “PRO2PRO” WITH GERRY 6 7 7 CONWAY & DAN JURGENS 2 8 5 6 And the team fans 2 8 love to hate — 1 “JUSTICE LEAGUE DETROIT”! The Retro Comics Experience! Volume 1, Number 58 August 2012 Celebrating the Best Comics of the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR Michael “Superman”Eury PUBLISHER John “T.O.” Morrow GUEST DESIGNER Michael “BaTman” Kronenberg COVER ARTIST ISSUE! Luke McDonnell and Bill Wray . s c i m COVER COLORIST o C BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury .........................................................2 Glenn “Green LanTern” WhiTmore C D © PROOFREADER & Whoever was sTuck on MoniTor DuTy FLASHBACK: 22,300 Miles Above the Earth .............................................................3 M T . A look back at the JLA’s “Satellite Years,” with an all-star squadron of creators a c i r SPECIAL THANKS e m Jerry Boyd A Rob Kelly f o Michael Browning EllioT S! Maggin GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Unofficial JLA/Avengers Crossovers ................29 e u Rich Buckler g Luke McDonnell Never heard of these? Most folks haven’t, even though you might’ve read the stories… a e L Russ Burlingame Brad MelTzer e c i T Snapper Carr Mi ke’s Amazing s u J Dewey Cassell World of DC INTERVIEW: More Than Marvel’s JLA: Squadron Supreme ....................................33 e h T ComicBook.com Comics SS editor Ralph Macchio discusses Mark Gruenwald’s dictatorial do-gooders g n i r Gerry Conway Eri c Nolen- r a T s DC Comics WeaThingTon , ) 6 J. -

VICTOR FOX? STARRING: EISNER • IGER BAKER • FINE • SIMON • KIRBY TUSKA • HANKS • BLUM Et Al

Roy Tho mas ’ Foxy $ Comics Fan zine 7.95 No.101 In the USA May 2011 WHO’S AFRAID OF VICTOR FOX? STARRING: EISNER • IGER BAKER • FINE • SIMON • KIRBY TUSKA • HANKS • BLUM et al. EXTRA!! 05 THE GOLDEN AGE OF 1 82658 27763 5 JACK MENDELLSOHN [Phantom Lady & Blue Beetle TM & ©2011 DC Comics; other art ©2011 Dave Williams.] Vol. 3, No. 101 / May 2011 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll OW WITH Jerry G. Bails (founder) N Ronn Foss, Biljo White 16 PAGES Mike Friedrich LOR! Proofreader OF CO Rob Smentek Cover Artist David Williams Cover Colorist Contents Tom Ziuko Writer/Editorial – A Fanzine Is As A Fanzine Does . 2 With Special Thanks to: Rob Allen Allan Holtz/ The Education Of Victor Fox . 3 Heidi Amash “Stripper’s Guide” Richard Kyle’s acclaimed 1962 look at Fox Comics—and some reasons why it’s still relevant! Bob Andelman Sean Howe Henry Andrews Bob Hughes Superman Vs. The Wonder Man 1939 . 27 Ken Quattro presents—and analyzes—the testimony in the first super-hero comics trial ever. Ger Apeldoorn Greg Huneryager Jim Beard Paul Karasik “Cartooning Was Ultimately My Goal” . 59 Robert Beerbohm Denis Kitchen Jim Amash commences a candid conversation with Golden Age writer/artist Jack Mendelsohn. John Benson Richard Kyle Dominic Bongo Susan Liberator Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt! The Mystery Of Bill Bossert & Ulla Edgar Loftin The Missing Letterer . 69 Neigenfind-Bossert Jim Ludwig Michael T. -

![Fredric Wertham Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5775/fredric-wertham-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-1815775.webp)

Fredric Wertham Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

Fredric Wertham Papers A Finding Aid to the Collection in the Library of Congress Prepared by T. Michael Womack, with the assistance of Patricia Craig, Patrick Holyfield, Kathleen Kelly, Sherralyn McCoy, Brian McGuire, Scott McLemee, and Gregg Van Vranken Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2010 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2010 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms010146 Collection Summary Title: Fredric Wertham Papers Span Dates: 1818-1986 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1945-1975) ID No.: MSS62110 Creator: Wertham, Fredric, 1895-1981 Extent: 82,200 items; 222 containers plus 2 oversize; 90 linear feet Language: Collection material in English, with some German and French Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: Psychiatrist. Correspondence, memoranda, writings, speeches and lectures, reports, research notes, patient case files, psychiatric tests, transcripts of court proceedings, biographical information, newspaper clippings, drawings, photographs, and other materials pertaining primarily to Wertham's career in psychiatry. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Caldwell, Taylor, 1900-1985--Correspondence. Freud, Sigmund, 1856-1939--Correspondence. Frink, Horace Westlake, 1883-1936--Correspondence. Gutheil, Emil Arthur, 1899-1959--Correspondence. Hughes, Langston, 1902-1967--Correspondence. Jones, Ernest, 1879-1958--Correspondence. Kinsey, Alfred C. (Alfred Charles), 1894-1956--Correspondence. Kraepelin, Emil, 1856-1926. Lissitzky, El, 1890-1941. -

Nypd Red-Faced

SAVE CASH! FIND THIS WEEK’S BORO DEALS ON PAGE 11 Yo u r Neighborhood — Yo u r News® BrooklynPaper.com • (718) 260–2500 • Brooklyn, NY • ©2011 Serving Brownstone Brooklyn, Williamsburg & Bay Ridge AWP/16 pages • Vol. 34, No. 42 • October 21–27, 2011 • FREE NYPD RED-FACED Cops drop charges after high-profi le ‘fi end’ arrest By Kate Briquelet Cops then said that the 32-year- The Brooklyn Paper old Queens resident had been Embarrased cops collared a picked out of a lineup and con- second alleged sex fiend on Mon- The fi rst victim? nected to a May 7 incident where day — but were forced to drop a man grabbed a woman’s breasts, the charges two days later after Woman says cops ignore link exposed himself and masturbated the victim who supposedly picked in the entrance to the Seventh Av- him out of a lineup recanted. By Kate Briquelet than a year later. enue F-train station. It was a wild week for the NYPD, The Brooklyn Paper The 31-year-old victim told But the charge did hold up, and which first trumpeted the arrest A Carroll Gardens woman The Brooklyn Paper that she the masturbator got off, leaving of Joshua Flecha, a bartender at claims that she was the South realized that she was an early the NYPD empty-handed amid the Heartland Brewery in Man- Slope Sex Fiend’s first victim victim after seeing a shocking growing local frustration of the hattan, who was allegedly caught — but cops fumbled her case, video of the fiend’s first be- pace of the investigation of what masturbating between parked cars allowing the creep to terror- lieved attempted rape in March . -

2010 1:22 PM Page 1

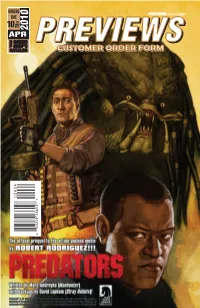

April 10 COF C1:COF C1.qxd 3/18/2010 1:22 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 10APR 2010 APR E E COMIC H H T T SHOP’S CATALOG Project7:Layout 1 3/15/2010 1:35 PM Page 1 COF Gem Page Apr:gem page v18n1.qxd 3/18/2010 2:07 PM Page 1 PREDATORS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BUZZARD #1 DARK HORSE COMICS GREEN ARROW #1 DC COMICS SUPERMAN #700 DC COMICS JURASSIC PARK: REDEMPTION #1 IDW PUBLISHING HACK/SLASH: MY FIRST MANIAC #1 MAGAZINE GEM OF THE MONTH IMAGE COMICS THE BULLETPROOF COFFIN #1 IMAGE COMICS WIZARD MAGAZINE #226 THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN #634 MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 3/18/2010 2:14 PM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS 1 THE ROYAL HISTORIAN OF OZ #1 G AMAZE INK/ SLAVE LABOR GRAPHICS CRITICAL MILLENNIUM #1 G ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT LLC DARKWING DUCK: THE DUCK KNIGHT RETURNS #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS DISNEY‘S ALICE IN WONDERLAND GN/HC G BOOM! STUDIOS RED SONJA #50 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT STARGATE: DANIEL JACKSON #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 GHOSTOPOLIS SC/HC G GRAPHIX THE WHISPERS IN THE WALLS #1 G HUMANOIDS INC STARDROP VOLUME 1 GN G I BOX PUBLISHING KRAZY KAT: A CELEBRATION OF SUNDAYS HC G SUNDAY PRESS BOOKS SIMON & KIRBY SUPERHEROES HC G TITAN PUBLISHING THE PLAYWRIGHT HC G TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS CHARMED #1 G ZENESCOPE ENTERTAINMENT INC BOOKS & MAGAZINES WILLIAM STOUT: HALLUCINATIONS SC/HC G ART BOOKS 2 SUCK IT, WONDER WOMAN! MISADVENTURES OF A HOLLYWOOD GEEK G HUMOR ASLAN: THE PIN-UP SC G INTERNATIONAL STAR WARS: THE OFFICIAL FIGURINE COLLECTION MAGAZINE G STAR WARS TOYFARE #156 G WIZARD ENTERTAINMENT CALENDARS 2 BONE 2011 WALL CALENDAR G COMICS VINTAGE -

Catalog 2018 General.Pdf

TERRY’S COMICS Welcome to Catalog number twenty-one. Thank you to everyone who ordered from one or more of our previous catalogs and especially Gold and Platinum customers. Please be patient when you call if we are not here, we promise to get back to you as soon as possible. Our normal hours are Monday through Friday 8:00AM-4:00PM Pacific Time. You can always send e-mail requests and we will reply as soon as we are able. This catalog has been expanded to include a large DC selection of comics that were purchased with Jamie Graham of Gram Crackers. All comics that are stickered below $10 have been omitted as well as paperbacks, Digests, Posters and Artwork and many Magazines. I also removed the mid-grade/priced issue if there were more than two copies, if you don't see a middle grade of an issue number, just ask for it. They are available on the regular web-site www.terryscomics.com. If you are looking for non-key comics from the 1980's to present, please send us your want list as we have most every issue from the past 35 years in our warehouse. Over the past two years we have finally been able to process the bulk of the very large DC collection known as the Jerome Wenker Collection. He started collecting comic books in 1983 and has assembled one of the most complete collections of DC comics that were known to exist. He had regular ("newsstand" up until the 1990's) issues, direct afterwards, the collection was only 22 short of being complete (with only 84 incomplete.) This collection is a piece of Comic book history.