The North Carolina General Assembly Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A 2010 Candidates

CANDIDATE NAME NAME ON BALLOT FILING DATE ADDRESS US SENATE (DEM) WILLIAMS, MARCUS W Marcus W. Williams 02/08/2010 PO BOX 1005 LUMBERTON, NC 28359 WORTHY, WILMA ANN Ann Worthy 02/24/2010 PO BOX 212 GASTONIA, NC 28053 MARSHALL, ELAINE Elaine Marshall 02/22/2010 324 S. WILMINGTON ST NO. 420 RALEIGH, NC 27601 LEWIS, KEN Ken Lewis 02/10/2010 629 KENSINGTON PLACE CHAPEL HILL, NC 27514 HARRIS, SUSAN Susan Harris 02/26/2010 390 BIG BEAR BLVD OLD FORT, NC 28762 CUNNINGHAM, JAMES CALVIN Cal Cunningham 02/11/2010 118 WEST THIRD AVE LEXINGTON, NC 27292 US SENATE (REP) LINNEY, LARRY ROLANDO Larry Linney 02/25/2010 6516-F YATESWOOD DRIVE CHARLOTTE, NC 28212 JONES, BRADFORD WESLEY Brad Jones 02/11/2010 PO BOX 181 LAKE TOXAWAY, NC 28747 BURKS, EDWARD JAMES Eddie Burks 02/08/2010 616 OLD LIBERTY RD ASHEBORO, NC 27203 BURR, RICHARD Richard Burr 02/22/2010 2634 FOREST DRIVE WINSTON-SALEM, NC 27104 US SENATE (LIB) BEITLER, MICHAEL Michael Beitler 02/08/2010 2709 CURRIETON COURT OAK RIDGE, NC 27310 US HOUSE DISTRICT 1 (DEM) LARKINS, CHAD Chad Larkins 02/23/2010 266 CARROLL TOWN ROAD MACON, NC 27551 BUTTERFIELD, GK G. K. Butterfield 02/15/2010 PO BOX 2571 WILSON, NC 27894 CANDIDATE NAME NAME ON BALLOT FILING DATE ADDRESS US HOUSE DISTRICT 1 (REP) WOOLARD, ASHLEY Ashley Woolard 02/15/2010 PO BOX 1116 WASHINGTON, NC 27889 MILLER, JAMES GORDON Jim Miller 02/18/2010 700 S. MEMORIAL BLVD KILL DEVIL HILLS, NC 27948 GRIMES, JERRY Jerry Grimes 02/12/2010 704 SOUTH MADISON AVENUE GOLDSBORO, NC 27530 CARTER, JOHN John Carter 02/15/2010 5313 CARTER ROAD WILSON, NC 27893 US HOUSE DISTRICT 2 (DEM) ETHERIDGE, BOB Bob Etheridge 02/08/2010 PO BOX 28001 RALEIGH, NC 27611 US HOUSE DISTRICT 2 (REP) GAILAS, TODD Todd Gailas 02/19/2010 148 PRESTONIAN PLACE MORRISVILLE, NC 27560 ELLMERS, RENEE Renee Ellmers 02/23/2010 PO BOX 904 DUNN, NC 28335 DEATRICH, FRANK Frank Deatrich 02/08/2010 781 RANSDELL ROAD LOUISBURG, NC 27549 US HOUSE DISTRICT 2 (LIB) ROSE, TOM Tom Rose 02/08/2010 PO BOX 518 BENSON, NC 27504 US HOUSE DISTRICT 3 (DEM) ROUSE, JOHNNY G Johnny G. -

House/Senate District Number Name House 10 John Bell House 17 Frank Iler House 18 Deb Butler House 19 Ted Davis, Jr

House/Senate District Number Name House 10 John Bell House 17 Frank Iler House 18 Deb Butler House 19 Ted Davis, Jr. House 20 Holly Grange House 23 Shelly Willingham House 24 Jean Farmer Butterfield House 26 Donna McDowell White House 27 Michael H. Wray House 28 Larry C. Strickland House 31 Zack Hawkins House 32 Terry Garrison House 33 Rosa U. Gill House 34 Grier Martin House 35 Chris Malone House 36 Nelson Dollar House 37 John B. Adcock House 38 Yvonne Lewis Holley House 39 Darren Jackson House 41 Gale Adcock House 42 Marvin W. Lucas House 43 Elmer Floyd House 44 Billy Richardson House 45 John Szoka House 49 Cynthia Ball House 50 Graig R. Meyer House 51 John Sauls House 52 Jamie Boles House 53 David Lewis House 54 Robert T. Reives, II House 55 Mark Brody House 57 Ashton Clemmons House 58 Amos Quick House 59 Jon Hardister House 60 Cecil Brockman House 62 John Faircloth House 66 Ken Goodman House 68 Craig Horn House 69 Dean Arp House 70 Pat B. Hurley House 72 Derwin Montgomery House 74 Debra Conrad House 75 Donny C. Lambeth House 77 Julia Craven Howard House 82 Linda P. Johnson House 85 Josh Dobson House 86 Hugh Blackwell House 87 Destin Hall House 89 Mitchell Smith Setzer House 90 Sarah Stevens House 91 Kyle Hall House 92 Chaz Beasley House 95 John A. Fraley House 96 Jay Adams House 97 Jason R. Saine House 98 John R. Bradford III House 102 Becky Carney House 103 Bill Brawley House 104 Andy Dulin House 105 Scott Stone House 106 Carla Cunningham House 107 Kelly Alexander House 108 John A. -

Progress Report to Highlight the Issues (I.E

ONE STEP FORWARD, TWO STEPS BACK FOR CLEAN ENERGY? Representatives Dean Arp, John Szoka, and Sam Watford introduced House Bill 589, “Competitive Energy Solutions for North Carolina” during the 2017 session. This bill took small steps towards increasing the role solar plays in the state’s energy mix by creating a competitive bidding process and by expanding rooftop solar. Senator Harry Brown added a moratorium on wind energy projects, claiming NC’s military operations would be under threat by wind turbines. Senator Brown used the once bipartisan supported clean energy bill as an attempt to pit solar against wind. Governor Cooper refused to allow Brown to claim victory: after signing H589 into law, Cooper immediately issued an executive order to the Dept. of Environmental Quality asking for the expedition of wind project permits. No 18-month ban will stop this clean energy source from moving forward. WATER, AIR, AND HEALTH Legislators continued to put the water, air, and health of North Carolinians at risk throughout the 2017 legislative long session. State lawmakers approved a bill that would allow companies to spray “garbage juice” into our air; passed a policy that limits the amount of financial compensation a resident or property owner can receive for detrimental health and livelihood impacts in hog pollution or other nuisance cases; and thumbed their noses at local control over environmental safeguards by prohibiting state regulators from making stricter water quality rules than the federal standards (assuming those even exist). Overall, leaders of the General Assembly showed a lack of empathy for their constituents and clear preference for polluters with deep pockets in 2017. -

Public Comments Received

NORTH CAROLINA GENERAL ASSEMBLY STATE LEGISLATIVE BUILDING 16 W. Jones Street Raleigh, North Carolina 27601-1030 March 5, 2020 Jamille Robbins NC Department of Transportation– Environmental Analysis Unit 1598 Mail Service Center Raleigh, NC 27699-1598 Submitted via email: [email protected] Re: Modernization of outdoor advertising rules 19A NCAC 02E .0225 To the NC Department of Transportation, We are North Carolina legislators who care about the scenic beauty of our state and We are writing to oppose the proposed changes to the modernization of outdoor advertising rules (19A NCAC 02E .0225) that would limit local ordinances and allow billboards with a state permit to be converted to digital and raised to 50 feet in height, even if such changes are not allowed by the applicable city or county ordinance. Instead, we support the considered “Alternative 2” described in the agency’s March 1, 2019, fiscal note. Alternative 2 would recognize local government ordinances and limit the changes that could be made to an existing billboard as part of modernization. Alternative 2 as described in the fiscal note: “The second alternate is to further limit activities that industry could do as part of modernization. An example includes restricting companies to modernize from static to digital faces. Some local governments have more stringent rules associated with outdoor advertising regulations including moratoriums on allowing digital billboards. NCDOT considered excluding digital faces as part of modernization. NCDOT chose not to make this exclusion since the state already allows digital billboards and that industry should be allowed to accommodate for technology enhancements.” We wish to protect the ability of local communities to control billboards, especially taller, digitized billboards that impact the scenic beauty of North Carolina and can be a distraction to drivers. -

Ch 5 NC Legislature.Indd

The State Legislature The General Assembly is the oldest governmental body in North Carolina. According to tradition, a “legislative assembly of free holders” met for the first time around 1666. No documentary proof, however, exists proving that this assembly actually met. Provisions for a representative assembly in Proprietary North Carolina can be traced to the Concessions and Agreements, adopted in 1665, which called for an unicameral body composed of the governor, his council and twelve delegates selected annually to sit as a legislature. This system of representation prevailed until 1670, when Albemarle County was divided into three precincts. Berkeley Precinct, Carteret Precinct and Shaftsbury Precinct were apparently each allowed five representatives. Around 1682, four new precincts were created from the original three as the colony’s population grew and the frontier moved westward. The new precincts were usually allotted two representatives, although some were granted more. Beginning with the Assembly of 1723, several of the larger, more important towns were allowed to elect their own representatives. Edenton was the first town granted this privilege, followed by Bath, New Bern, Wilmington, Brunswick, Halifax, Campbellton (Fayetteville), Salisbury, Hillsborough and Tarborough. Around 1735 Albemarle and Bath Counties were dissolved and the precincts became counties. The unicameral legislature continued until around 1697, when a bicameral form was adopted. The governor or chief executive at the time, and his council constituted the upper house. The lower house, the House of Burgesses, was composed of representatives elected from the colony’s various precincts. The lower house could adopt its own rules of procedure and elect its own speaker and other officers. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ..................................................................................................... iii INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................ 2 ARGUMENT .............................................................................................................................. 5 I. Legislative Defendants Must Provide the Information Requested in the Second Set of Interrogatories ............................................................................................................. 5 II. In the Alternative, or if Legislative Defendants Do Not Provide The Home Addresses By March 1, the Court Should Bar Legislative Defendants From Defending the 2017 Plans on the Basis of Any Incumbency Theory................................. 7 III. The Court Should Award Fees and Expenses and Other Appropriate Relief ..................... 8 CONCLUSION ........................................................................................................................... 9 CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE .................................................................................................. 11 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) Cases Cloer v. Smith , 132 N.C. App. 569, 512 S.E.2d 779 (1999)............................................................................ 7 F. E. Davis -

Good Government Fund Contributions to Candidates and Political Committees January 1 ‐ December 31, 2018

GOOD GOVERNMENT FUND CONTRIBUTIONS TO CANDIDATES AND POLITICAL COMMITTEES JANUARY 1 ‐ DECEMBER 31, 2018 STATE RECIPIENT OF GGF FUNDS AMOUNT DATE ELECTION OFFICE OR COMMITTEE TYPE CA Jeff Denham, Jeff PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC DC Association of American Railroads PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Trade Assn PAC FL Bill Nelson, Moving America Forward PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC GA David Perdue, One Georgia PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC GA Johnny Isakson, 21st Century Majority Fund Fed $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC MO Roy Blunt, ROYB Fund $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC NE Deb Fischer, Nebraska Sandhills PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC OR Peter Defazio, Progressive Americans for Democracy $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC SC Jim Clyburn, BRIDGE PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC SD John Thune, Heartland Values PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC US Dem Cong Camp Cmte (DCCC) ‐ Federal Acct $15,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 National Party Cmte‐Fed Acct US Natl Rep Cong Cmte (NRCC) ‐ Federal Acct $15,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 National Party Cmte‐Fed Acct US Dem Sen Camp Cmte (DSCC) ‐ Federal Acct $15,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 National Party Cmte‐Fed Acct US Natl Rep Sen Cmte (NRSC) ‐ Federal Acct $15,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 National Party Cmte‐Fed Acct VA Mark Warner, Forward Together PAC $5,000 01/18/2018 N/A 2018 Federal Leadership PAC VA Tim Kaine, Common -

North Carolina Legislative Update, January 11, 2019

North Carolina Legislative Update, January 11, 2019 01.11.2019 State legislators returned to Raleigh this week to begin the 2019 session. This year’s session, which is called the “long session,” is expected to last through the summer as members enact a two-year budget and consider hundreds of bills. Republicans continue to hold majorities in both houses, but after the 2018 election, their majorities are no longer veto proof. They hold a 29-21 majority in the Senate and 65-55 in the House. A number of seats are held by newcomers—13 Senators and 26 Representatives. The chief business for opening day was election of leadership. Both chambers elected many of the same leaders as the past session. The Senate reelected Senator Phil Berger (R-Rockingham) as President Pro Tem and Senator Ralph Hise (R-Mitchell) as Deputy President Pro Tem. Senator Dan Blue (D-Wake) was reelected as Democratic leader. The House reelected Representative Tim Moore (R-Cleveland) as Speaker and Representative Sarah Stevens (R-Surry) as Speaker Pro Tem. Representative Darren Jackson (D-Wake) was reelected as Democratic leader. Senior Chairs of the House Appropriations Committee will be Representatives Jason Saine (R-Lincoln), Linda Johnson (R-Cabarrus), and Donny Lambeth (R-Forsyth). The Chairs of the House Finance Committee will be Representatives Julia Howard (R-Davie), Mitchell Setzer (R-Catawba), and John Szoka (R-Cumberland). Representative David Lewis (R-Harnett) will remain Chairman of the House Committee on Rules, Calendar and Operations of the House. Three Senators will continue to chair the Appropriations/Base Budget committee. -

Journal Senate 2015 General

JOURNAL OF THE SENATE OF THE 2015 GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA SECOND EXTRA SESSION 2016 OFFICERS AND MEMBERS OF THE SENATE OF THE NORTH CAROLINA 2015 GENERAL ASSEMBLY SECOND EXTRA SESSION 2016 SENATE LEADERSHIP DANIEL J. FOREST, President ......................................................... Raleigh PHILIP E. BERGER, President Pro Tempore ........................................ Eden LOUIS M. PATE, JR., Deputy President Pro Tempore .............. Mount Olive DISTRICT NAME OF SENATOR RESIDENCE 1 WILLIAM COOK (R) ........................................... Chocowinity 2 NORMAN W. SANDERSON (R) ............................. Arapahoe 3 ERICA SMITH-INGRAM (D) ...................................... Gaston 4 ANGELA R. BRYANT (D) ................................. Rocky Mount 5 DONALD G. DAVIS (D) ......................................... Snow Hill 6 HARRY BROWN (R) ............................................ Jacksonville 7 LOUIS M. PATE, JR. (R) ..................................... Mount Olive 8 WILLIAM P. RABON (R)......................................... Southport 9 MICHAEL V. LEE (R) .......................................... Wilmington 10 BRENT JACKSON (R) ............................................ Autryville 11 E. S. “BUCK” NEWTON III (R) ................................... Wilson 12 RONALD J. RABIN (R) ........................................ Spring Lake 13 JANE W. SMITH (D) .............................................. Lumberton 14 DANIEL T. BLUE, JR. (D) .......................................... Raleigh 15 -

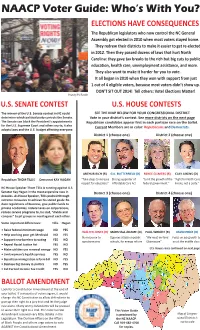

NAACP Voter Guide: Who’S with You?

NAACP Voter Guide: Who’s With You? ELECTIONS HAVE CONSEQUENCES The Republican legislators who now control the NC General Assembly got elected in 2010 when most voters stayed home. They redrew their districts to make it easier to get re-elected in 2012. Then they passed dozens of laws that hurt North Carolina: they gave tax breaks to the rich but big cuts to public education, health care, unemployment assistance, and more. They also want to make it harder for you to vote. It all began in 2010 when they won with support from just 1 out of 4 eligible voters, because most voters didn’t show up. DON’T SIT OUT 2014! Tell others: Vote! Elections Matter! Photo by Phil Fonville U.S. SENATE CONTEST U.S. HOUSE CONTESTS The winner of the U.S. Senate contest in NC could SEE THE MAP BELOW FOR YOUR CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT determine which political party controls the Senate. Vote in your district’s contest. See more districts on the next page The Senate can block the President’s appointments Republican candidates appear first in each partisan race on the ballot. for the U.S. Supreme Court and other courts; it also Current Members are in color: Republicans and Democrats. adopts laws and the U.S. budget affecting everyone. District 1 (choose one) District 2 (choose one) ARTHUR RICH (R) G.K. BUTTERFIELD (D) RENEE ELLMERS (R) CLAY AIKENS (D) Republican THOM TILLIS Democrat KAY HAGAN “Take steps to increase Strong supporter of “Limit the growth of the “Fight for North Caro- respect for educators” Affordable Care Act federal government.” linians, not a party.” NC House Speaker Thom Tillis is running against U.S. -

The Racial Justice Act and the Long Struggle with Race and the Death Penalty in North Carolina*

MOSTELLER&KOTCH.PTD2 9/18/10 12:07 PM THE RACIAL JUSTICE ACT AND THE LONG STRUGGLE WITH RACE AND THE DEATH PENALTY IN NORTH CAROLINA* SETH KOTCH & ROBERT P. MOSTELLER** In August 2009, the North Carolina General Assembly enacted the Racial Justice Act (“RJA”), which commands that no person shall be executed “pursuant to any judgment that was sought or obtained on the basis of race.” One of the most significant features of the RJA is its use of statistical evidence to determine whether the race of defendants or victims played a significant role in death penalty decisions by prosecutors and jurors and in the prosecutor’s exercise of peremptory challenges. The RJA commits North Carolina courts to ensuring that race does not significantly affect death sentences. This Article examines the RJA and North Carolina’s long struggle with race and the death penalty. The first part traces the history of race and the death penalty in the state, showing that racial prejudice exerted a consistent, strong, and pernicious influence on the imposition and disposition of death sentences. From colonial times into the 1960s, the overwhelming majority of those executed were African American, and although most victims and perpetrators of crime are of the same race, the overwhelming majority of victims in cases where executions took place were white. Hundreds of African Americans have been executed for a variety of crimes against white victims, including scores of African American men executed for rape. However, just four whites have been executed for crimes against African American victims, all murders. * © 2010 Seth Kotch & Robert P. -

To the User | NCCPPR

Search this Site North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research ...Your source for nonpartisan research & analysis Home › NC Legislature › Citizens' Guide to the 2011-2012 N.C. Legislature Citizens' Guide to the 2011-2012 N.C. Legislature To The User How to Use the Citizens' Guide to the Legislature The North Carolina Senate Profiles of NC Senators The North Carolina House of Representatives Profiles of NC Representatives Legislative Session Information Rankings of Legislators' Effectiveness, Attendance, Roll Call Participation, and Most Influential Lobbyists Click Here To Take A Video Tour of the Online Guide Trends in the North Carolina General Assembly N.C. Center for Public Policy Donate Now » Join Now » Research Support our work, and thereby Become a part of th 5 W. Hargett St., Suite 01 North Carolina citizens, by Stay informed on th P.O. Box 430 donating through the Network policy development Raleigh, NC 27602 for Good, a donation site for world. nonprofit groups. 919-832-2839 919-832-2847 Search this Site North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research ...Your source for nonpartisan research & analysis Home › NC Legislature › Citizens' Guide to the 2011-2012 N.C. Legislature › To The User To The User An informed electorate is the essence of democratic government, but more than a general understanding of important issues is required if government is to fully serve the public’s interests. Informed citizens must also know something about the men and women elected to serve them as legislators. This guide has been prepared to acquaint the people of North Carolina with their state Senators and Representatives.