Talking Place: Unfolding Conversations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artist Résumé Pippin Drysdale

Artist Résumé Pippin Drysdale www.pippindrysdale.com Education 1985 Bachelor of Art (Fine Art), Western Australian Institute of Technology (WAIT), now Curtin University, Perth, Western Australia 1982 Study and work tour: Perugia, Italy; Anderson Ranch, Colorado, USA; San Diego, USA 1982 Diploma in Advanced Ceramics, Western Australian School of Art and Design Grants 2007 Australia Council for the Arts, Visual Arts and Craft Board, Major Fellowship 2006 ArtsWA Project Grant, John Curtin Gallery, Curtin University, Survey/Installation Western Australia 2005 ArtsWA Freight & Travel, Carlin Gallery, Paris 2003 ArtsWA Freight and Travel, Victoria and Albert Museum, London COLLECT 2002 ArtsWA Catalogue, Freight & Travel, Germany 2001 Australia Council for the Arts Visual Arts and Craft Fund, Germany tour 1998 ArtsWA Creative Development Fellowship 1997/8 Australia Council for the Arts Visual Arts and Craft Fund, Project Grant 1997 ArtsWA Travel Grant 1994 Australia Council for the Arts Visual Arts and Craft Board, Creative Development 1992 ArtsWA Travel Grant 1991 ArtsWA Travel Grant 1990 Australia Council for the Arts Visual Art and Craft Board, Creative Development 1987 Australia Council for the Arts Visual Art and Craft Board, Special Development 1 Awards 2020 Honorary Doctorate of the Arts, Curtin University, Perth, Western Australia 2015 WA State Living Treasure Award, Western Australian Government 2011 Artsource Lifetime Achievement Award, Perth, Western Australia 2007 Master of Australian Craft, Craft Australia, New South Wales, Australia -

2020 Vision Inside

Thursday, November 5, 2020 perthnow.com.au/community-news 2020 VISION It’s the view that could save lives this summer Page 4 INSIDE Cockburn Cement pleads not guilty in case of EMISSION OVERLOAD Ben Smith Cockburn Cement Limited. tions by the department Court on Monday morning, The company has been into ongoing complaints which followed an initial TEENS A MAJOR cement and lime charged with 15 counts of about odour and dust in the appearance in September. plant that has previously emitting an unreasonable Cockburn area. A trial allocation date drawn the ire of locals has emission from any prem- Penalties of up to was set for February 16. BACK ON pleaded not guilty to alle- ises, with the alleged $125,000 for each offence Part of the Adelaide gations of unreasonable breaches of the Environ- may be imposed for a body Brighton Group, the Mun- emissions. mental Protection Act said corporate on conviction. ster plant is one of the TRACK The Department for to have occurred between A Cockburn Cement rep- State’s major manufactur- Water and Environmental January and April in 2019. resentative entered the ers of concrete and lime. PAGE 5 Regulation has begun pros- The prosecution follows plea of not guilty in writing ecution action against several years of investiga- to Perth Magistrate’s CONTINUED PAGE 3 FRE 2 NEWS November 5, 2020 NEWS ...................................................................... P1-17 POWER TO THE PEOPLE EDUCATION MATTERS............................................ P16 ZEST FOR LIFE OVER 55 FEATURE ................ P20-24 FILM .......................................................................... P25 Switch flicked in Hilton BOOKS ...................................................................... P26 LOCAL SPOTLIGHT FEATURE ............................... P27 Adam Poulsen boundary area will have to “Overhead power net- the bill, covering all capital REAL ESTATE ................................................... -

THROWN TOGETHER Pippin Drysdale and Warrick Palmateer’S Confluence Is the Result of a Unique Pairing, Writes Victoria Laurie

13 Oct 2018 Weekend Australian, Australia Author: Victoria Laurie • Section: Review • Article Type: News Item • Audience : 219,242 Page: 12 • Printed size: 696.00cm² • Region: National • Market: Australia ASR: AUD 22,729 • words: 1141 • Item ID: 1021050570 Licensed by Copyright Agency. You may only copy or communicate this work with a licence. Page 1 of 3 THROWN TOGETHER Pippin Drysdale and Warrick Palmateer’s Confluence is the result of a unique pairing, writes Victoria Laurie f any art show was ever likely to capture the The elegant shapes, the luminous glazes, essence of both Australia’s inland and its even the musical note emitted by gently tapping jagged coastline, Confluence is it. Ceramic the eggshell-thin rim of her vessels — all have Iartist Pippin Drysdale, now into her fifth earned Drysdale a reputation as one of Aust- decade of creating exquisite clay vessels, ralia’s foremost ceramic artists and, in 2015, the says she has always looked for inspiration in title of West Australian State Living Treasure. deserts such as the Great Sandy and Tanami in “I’ve never wanted to be just a mugs, jugs Western Australia’s remote heart. and casserole person; I’ve always wanted to Her co-exhibitor in a John Curtin Gallery make my mark,” she told Review in 2007 when show is Warrick Palmateer, a tall, musclebound her retrospective show was held at the John surfer cum potter who finds inspiration as he Curtin Gallery. paddles beyond the ocean reef at Yanchep most Then, as now, her appetite for adventure mornings before a day spent sitting at a potter’s exposed her to landscapes she found inspiring, wheel in Drysdale’s Fremantle studio. -

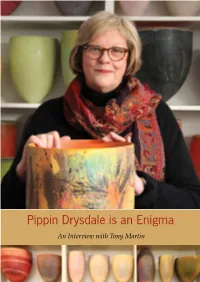

Pippin Drysale Is an Enigma: an Interview with Tony Martin

Avondale College ResearchOnline@Avondale Arts Papers and Journal Articles School of Humanities and Creative Arts 2014 Pippin Drysale is an Enigma: An Interview with Tony Martin Tony Martin Avondale College of Higher Education, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://research.avondale.edu.au/arts_papers Part of the Fine Arts Commons Recommended Citation Martin T. (2014). Pippin Drysdale is an enigma. Ceramics Art and Perception, 24(1), 8-13. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Humanities and Creative Arts at ResearchOnline@Avondale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts Papers and Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@Avondale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pippin Drysdale is an Enigma An Interview with Tony Martin xtravagant, generous, boisterous, larger-than- considering the work of Drysdale, that separation life and extroverted are words that spring to seems impossible. Her art and her life are so mind. A swirling, exuberant and rebellious inextricably linked that to view either in isolation is Epersonality that completely dominates any space to risk profoundly misunderstanding both. combined with a seeming total disregard for social Drysdale grew up in a well-to-do household in convention. Controversial, contradictory, creative Perth, Western Australia. Pretty, pampered and and euphoric coexist uneasily with troubling self- spoilt, she recalls an idyllic childhood clouded only doubt and deep insecurities. Combine wondrous by a struggle with schoolwork. Her teenage years dinner parties, holy men, high society, booming saw her throw herself into everything, except study, laughter and exotic lovers with a tumultuous private with unbridled gusto – resulting in the parting of life and a love for the outrageous and the picture ways with a number of exclusive private schools. -

Pippin Drysdale

609 Elizabeth Street REDFERN NSW 2016 AUSTRALIA . PO Box 1126 STRAWBERRY HILLS NSW 2012 www.sabbiagallery.com [email protected] DR PIPPIN DRYSDALE Education 2020 Honorary Doctorate, Curtin University of Technology, Perth, WA 1985 Bachelor of Art (Fine Art), Curtin University of Technology, Perth, WA 1982 Study and work tour: Perugia, Italy; Anderson Ranch, Colorado, USA; San Diego, USA 1982 Diploma in Advanced Ceramics, Western Australian School of Art and Design Selected Solo Exhibitions 2018 Convergence, John Curtin Gallery – Seventeen installations from the Devil’s Marbles collection (2017/18) 2017 Sabbia Gallery, Sydney – “Wild Alchemy” PULS Galerie, Brussels 2016 Mossgreen Gallery Melbourne – The Devil’s Marbles 2015 Mossgreen Gallery-Brans, Perth, Western Australia Mossgreen Gallery, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia Galerie Marianne Heller, Heidelberg, Germany 2014 Tanami Mapping III: Sabbia Gallery, Sydney, NSW, Australia Mossgreen Gallery, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia PULS Ceramics, Brussels, Belgium 2011 Mobilia Gallery, Boston, MA, USA 2010/11 Mobilia Gallery, Boston, MA, USA 2010 Mobilia Gallery, Boston, MA, USA Houston Centre for Contemporary Craft Museum, Houston, TX, USA Australian Embassy, Washington D.C., USA PULS Gallery, Brussels, Belgium 2009 Booker Lowe Gallery, Houston, USA 2008 Anant Art Gallery, Delhi, India PULS Gallery, Brussels, Belgium 2008 V&A, COLLECT Art Fair, London, UK 2007 Marianne Heller Gallery, Heidelberg, Germany Yamaki Gallery, Osaka, Japan John Curtin Gallery, ‘Lines of Site, Perth, Australia -

META 2020 3 - 22 August Mon - Fri 10Am - 4.30Pm; Sat 12 - 2.30Pm Gallery Central 12 Aberdeen Street, Perth

META 2020 3 - 22 August Mon - Fri 10am - 4.30pm; Sat 12 - 2.30pm Gallery Central 12 Aberdeen Street, Perth, www.gallerycentral.com.au Showcasing innovative and exciting creative works completed by year 11 and 12 students enrolled in Visual Art and Design courses, META complements North Metro TAFE’s prestigious art and design programs and acknowledges the excellence and originality of budding artist/designers in senior secondary schools across WA. Jessica Abreu Applecross Senior High School Year 11 More Than Comfort Digital Animation with elements of charcoal, photography, and watercolour This animation that was largely made through Adobe Pho- toshop. The animation shows a character walking through rooms, all drawn with different mediums while she’s strictly drawn digitally. I used digital art, charcoal, photography, and watercolours to create each unique setting and combine them. The main idea I wanted to convey was stepping out of com- fort. I aimed to take the audience on a journey with a char- acter who starts in a place of comfort, catches a glimpse of something more and pushes through uncertainty to get there. Kristian Almario Thornlie Senior High School Year 12 Behind Schedule Acrylic on paper I live in an extremely stressful time as a year 12 student who aims to go to university, with unstable circumstances for the 2020 Aus- tralian Tertiary Admission Rank (ATAR) because of COVID-19. I need to manage my schedule of work and adjust the time accord- ing to this fluctuating situation. I feel we have lived in a war situ- ation. I depict myself in this painting as one who is trying hard to manage this harsh and difficult times. -

Dr Pippin Drysdale

609 Elizabeth Street REDFERN NSW 2016 AUSTRALIA . PO Box 1126 STRAWBERRY HILLS NSW 2012 www.sabbiagallery.com [email protected] DR PIPPIN DRYSDALE Education 2020 Honorary Doctorate, Curtin University of Technology, Perth, WA 1985 Bachelor of Art (Fine Art), Curtin University of Technology, Perth, WA 1982 Study and work tour: Perugia, Italy; Anderson Ranch, Colorado, USA; San Diego, USA 1982 Diploma in Advanced Ceramics, Western Australian School of Art and Design Selected Solo Exhibitions 2018 Convergence, John Curtin Gallery – Seventeen installations from the Devil’s Marbles collection (2017/18) 2017 Sabbia Gallery, Sydney – “Wild Alchemy” PULS Galerie, Brussels 2016 Mossgreen Gallery Melbourne – The Devil’s Marbles 2015 Mossgreen Gallery-Brans, Perth, Western Australia Mossgreen Gallery, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia Galerie Marianne Heller, Heidelberg, Germany 2014 Tanami Mapping III: Sabbia Gallery, Sydney, NSW, Australia Mossgreen Gallery, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia PULS Ceramics, Brussels, Belgium 2011 Mobilia Gallery, Boston, MA, USA 2010/11 Mobilia Gallery, Boston, MA, USA 2010 Mobilia Gallery, Boston, MA, USA Houston Centre for Contemporary Craft Museum, Houston, TX, USA Australian Embassy, Washington D.C., USA PULS Gallery, Brussels, Belgium 2009 Booker Lowe Gallery, Houston, USA 2008 Anant Art Gallery, Delhi, India PULS Gallery, Brussels, Belgium 2008 V&A, COLLECT Art Fair, London, UK 2007 Marianne Heller Gallery, Heidelberg, Germany Yamaki Gallery, Osaka, Japan John Curtin Gallery, ‘Lines of Site, Perth, Australia -

Taca Agm Minutes 29 Sept 2019

ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING 2019 SUNDAY 29 SEPTEMBER 2019, 2pm Powerhouse Museum Theatrette, Floor 2, 500 Harris St, Ultimo NSW 2007 Chair: Dr Cathy Franzi 1. Present: Cathy Franzi, Avi Amesbury, Amanda Bromfield, Kate Jones, Vicki Grima, Dennis Woollam, Montessa Maack, John Dermer, Elisabeth Johnson, Sue Buckle, Gillian Hodes, Svetlana Panov, Sean Jackson, Tania Rollond, Melanie Jayne Hearn, Tony Schlosser, Alana Wilson, Iona Currie, Mike Hall, Jacqueline McBeath, Godelieve Mols, Ri Van Veen, Helen Earl, Nicola Coady, Sandy Jacka, Toni Warburton, Karen Weiss (along with a few more who didn’t sign in) Apologies: Holly Macdonald, Lou McCallum, Greg Crowe, Cher Shackleton, Poppe Davis, Alistair Whyte, Ursula Burgoyne, Judy Boydell, Jo Wood, Barry Jackson, Chair: there being more than 7 members present, I declare a Quorum and declare the meeting open at 2.10pm 2. Minutes of the previous Annual General Meeting 21 October 2018. Motion: that the Minutes of the previous Annual General Meeting 21 October 2018 be accepted as an accurate record of that meeting. Proposed: Avi Amesbury; seconded: Amanda Bromfield; all in favour. 3. Business arising from previous AGM 2018 minutes None. 4. Financial Statements: To receive, consider and adopt the audited financial statements for the financial year ended 30 June 2019. Dennis Woollam (auditor) presented the Financial Statements for the year ended 30 June 2019 (tabled). The profit of $32,120 is a positive result for TACA. The Online Masterclasses were a good initiative and have, so far, been profitable. It is hoped they will remain viable into the future. TACA’s engagement with social media is impressive, and keeps TACA connected with the wider community, one of the reasons for membership growth. -

Pippin Drysdale Is an Enigma

Pippin Drysdale is an Enigma An Interview with Tony Martin xtravagant, generous, boisterous, larger-than- considering the work of Drysdale, that separation life and extroverted are words that spring to seems impossible. Her art and her life are so mind. A swirling, exuberant and rebellious inextricably linked that to view either in isolation is Epersonality that completely dominates any space to risk profoundly misunderstanding both. combined with a seeming total disregard for social Drysdale grew up in a well-to-do household in convention. Controversial, contradictory, creative Perth, Western Australia. Pretty, pampered and and euphoric coexist uneasily with troubling self- spoilt, she recalls an idyllic childhood clouded only doubt and deep insecurities. Combine wondrous by a struggle with schoolwork. Her teenage years dinner parties, holy men, high society, booming saw her throw herself into everything, except study, laughter and exotic lovers with a tumultuous private with unbridled gusto – resulting in the parting of life and a love for the outrageous and the picture ways with a number of exclusive private schools. becomes a little more complete. Her later teenage years coincided with the beginning And then there is Pippin Drysdale’s art. Serenely of the 1960s. It was a cosmic alignment – Pippin confident, superbly crafted ceramic pieces are unlike Drysdale and the 1960s were made for each other. anything you have ever seen or even imagined. Moneyed, indulged and headstrong, Drysdale Beautifully elegant curves, assured decoration and revelled in the new found freedom of the times. ethereal colours combine to produce works that Melbourne, Sydney, US, London and Europe became seem to float effortlessly above impossibly small a playground for the quintessential good time girl. -

Ceramic Art & Perception

Ceramics: Art and Perception Volume 19 Issue 3 Volume Art and Perception Ceramics: 2009 Ceramics ISSUE 77 INTERNATIONAL Art and Perception AU$18 US$18 UK £9 CAN$20 €15 Print Post Publication No. PP255003100105 September – November 2009 77 Pippin Drysdale The Kimberley Series The Tanami Traces Series Article by Ted Snell HE KIMBERLEY SERIES IS A GROUP OF WORKS BASED memories and linked them to the mature vision of an on the artist’s experience of travelling in the artist. Over the following decade, she has explored northwest region of Western Australia. The ways in which this imagery might inform her work. Tnorthwest has been lodged in Pippin Drysdale’s However, the confluence of ideas and the oppor- psyche since her first visit while still a teenager in tunity to work on a major new project resulted in 1958, when she sailed on the MV Kanimbla to visit a new group of closed forms that investigates the Millstream Station, a property owned by the fam- Kimberley landscape anew. ily of a school friend. The landscape, its people, The process of distilling visual ideas to encapsu- the dramatic change of seasons and the remark- late the unique qualities of the topography, the flora, able geological structures were imprinted on her and the changing nature of the atmosphere from day brain. A trip back to the region in 1998 ignited those to night and summer through to winter is a long and 44 Ceramics: Art and Perception No. 77 2009 arduous process. It begins with the development of forlornly under the lemon tree are gems, flawed new forms. -

Drysdale P Biography

Pippin Drysdale Curriculum Vitae Born 1943, Melbourne, Australia 1982 Diploma in Advanced Ceramics, Western Australian School of Art and Design 1985 Curtin University, Western Australia, BA Fine Arts 1997 to date Adjunct Research Fellow, Curtin University, Western Australia 2008 Master of Australian Craft, Australia Council for the Arts Working in Fremantle, Western Australia “Working from her studio in Fremantle, surrounded by the catalogue of her trials and experiments – racks of wonderful pots of all colours and sizes that failed her almost impossible test of quality – Pippin Drysdale continues to interrogate her practice from the perspective of an artist without borders. The Falstaffian spirit that imbues her every action is pitched always at maximum intensity, from her explosive laugh - that fills not only rooms but auditoria - to her extravagant generosity and, of course, to her total commitment to her work. The landscape is the ever-constant lure, the catalyst for work, the connecting point and anchor for each new development. Her work is ambitious. It negotiates interweaving journeys through various landscapes describing her artistic practice and her engagement with the sites she documents. Through a continuing investigation of the flora and landforms of these unique areas of Australia and a commitment to engaging with the cultural, social and political agendas that are shaping them, she is open to embrace each new creative challenge.” Ted Snell AM CitWA, Director Cultural Precinct, University of Western Australia & Chair, Visual