Normal Stresses in Shear Flow Revised A.J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 1: Introduction

Lecture 1: Introduction E. J. Hinch Non-Newtonian fluids occur commonly in our world. These fluids, such as toothpaste, saliva, oils, mud and lava, exhibit a number of behaviors that are different from Newtonian fluids and have a number of additional material properties. In general, these differences arise because the fluid has a microstructure that influences the flow. In section 2, we will present a collection of some of the interesting phenomena arising from flow nonlinearities, the inhibition of stretching, elastic effects and normal stresses. In section 3 we will discuss a variety of devices for measuring material properties, a process known as rheometry. 1 Fluid Mechanical Preliminaries The equations of motion for an incompressible fluid of unit density are (for details and derivation see any text on fluid mechanics, e.g. [1]) @u + (u · r) u = r · S + F (1) @t r · u = 0 (2) where u is the velocity, S is the total stress tensor and F are the body forces. It is customary to divide the total stress into an isotropic part and a deviatoric part as in S = −pI + σ (3) where tr σ = 0. These equations are closed only if we can relate the deviatoric stress to the velocity field (the pressure field satisfies the incompressibility condition). It is common to look for local models where the stress depends only on the local gradients of the flow: σ = σ (E) where E is the rate of strain tensor 1 E = ru + ruT ; (4) 2 the symmetric part of the the velocity gradient tensor. The trace-free requirement on σ and the physical requirement of symmetry σ = σT means that there are only 5 independent components of the deviatoric stress: 3 shear stresses (the off-diagonal elements) and 2 normal stress differences (the diagonal elements constrained to sum to 0). -

Overview of Turbulent Shear Flows

Overview of turbulent shear flows Fabian Waleffe notes by Giulio Mariotti and John Platt revised by FW WHOI GFD Lecture 2 June 21, 2011 A brief review of basic concepts and folklore in shear turbulence. 1 Reynolds decomposition Experimental measurements show that turbulent flows can be decomposed into well-defined averages plus fluctuations, v = v¯ + v0. This is nicely illustrated in the Turbulence film available online at http://web.mit.edu/hml/ncfmf.html that was already mentioned in Lecture 1. In experiments, the average v¯ is often taken to be a time average since it is easier to measure the velocity at the same point for long times, while in theory it is usually an ensemble average | an average over many realizations of the same flow. For numerical simulations and mathematical analysis in simple geometries such as channels and pipes, the average is most easily defined as an average over the homogeneous or periodic directions. Given a velocity field v(x; y; z; t) we define a mean velocity for a shear flow with laminar flow U(y)^x by averaging over the directions (x; z) perpendicular to the shear direction y, 1 Z Lz=2 Z Lx=2 v¯ = lim v(x; y; z; t)dxdz = U(y; t)^x: (1) L ;L !1 x z LxLz −Lz=2 −Lx=2 The mean velocity is in the x direction because of incompressibility and the boundary conditions. In a pipe, the average would be over the streamwise and azimuthal (spanwise) direction and the mean would depend only on the radial distance to the pipe axis, and (possibly) time. -

Guide to Rheological Nomenclature: Measurements in Ceramic Particulate Systems

NfST Nisr National institute of Standards and Technology Technology Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce NIST Special Publication 946 Guide to Rheological Nomenclature: Measurements in Ceramic Particulate Systems Vincent A. Hackley and Chiara F. Ferraris rhe National Institute of Standards and Technology was established in 1988 by Congress to "assist industry in the development of technology . needed to improve product quality, to modernize manufacturing processes, to ensure product reliability . and to facilitate rapid commercialization ... of products based on new scientific discoveries." NIST, originally founded as the National Bureau of Standards in 1901, works to strengthen U.S. industry's competitiveness; advance science and engineering; and improve public health, safety, and the environment. One of the agency's basic functions is to develop, maintain, and retain custody of the national standards of measurement, and provide the means and methods for comparing standards used in science, engineering, manufacturing, commerce, industry, and education with the standards adopted or recognized by the Federal Government. As an agency of the U.S. Commerce Department's Technology Administration, NIST conducts basic and applied research in the physical sciences and engineering, and develops measurement techniques, test methods, standards, and related services. The Institute does generic and precompetitive work on new and advanced technologies. NIST's research facilities are located at Gaithersburg, MD 20899, and at Boulder, CO 80303. -

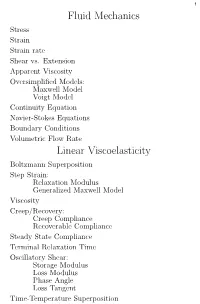

Fluid Mechanics Linear Viscoelasticity

1 Fluid Mechanics Stress Strain Strain rate Shear vs. Extension Apparent Viscosity Oversimplified Models: Maxwell Model Voigt Model Continuity Equation Navier-Stokes Equations Boundary Conditions Volumetric Flow Rate Linear Viscoelasticity Boltzmann Superposition Step Strain: Relaxation Modulus Generalized Maxwell Model Viscosity Creep/Recovery: Creep Compliance Recoverable Compliance Steady State Compliance Terminal Relaxation Time Oscillatory Shear: Storage Modulus Loss Modulus Phase Angle Loss Tangent Time-Temperature Superposition 1 2 Molecular Structure Effects Molecular Models: Rouse Model (Unentangled) Reptation Model (Entangled) Viscosity Recoverable Compliance Diffusion Coefficient Terminal Relaxation Time Terminal Modulus Plateau Modulus Entanglement Molecular Weight Glassy Modulus Transition Zone Apparent Viscosity Polydispersity Effects Branching Effects Die Swell 2 3 Nonlinear Viscoelasticity Stress is an Odd Function of Strain and Strain Rate Viscosity and Normal Stress are Even Functions of Strain and Strain Rate Lodge-Meissner Relation Nonlinear Step Strain Extra Relaxation at Rouse Time Damping Function Steady Shear Apparent Viscosity Power Law Model Cross Model Carreau Model Cox-Merz Empiricism First Normal Stress Coefficient Start-Up and Cessation of Steady Shear Nonlinear Creep and Recovery 3 4 Stress and Strain SHEAR F Shear Stress σ ≡ A l Shear Strain γ ≡ h dγ Shear Rate γ˙ ≡ dt Hooke’s Law σ = Gγ Newton’s Law σ = ηγ˙ EXTENSION F Tensile Stress σ ≡ A ∆l Extensional Strain ε ≡ l dε Extension Rate ε˙ ≡ dt Hooke’s Law σ =3Gε Newton’s Law σ =3ηε˙ 1 5 Viscoelasticity APPARENT VISCOSITY σ η ≡ γ˙ 1.Apparent Viscosity of a Monodisperse Polystyrene. 2 6 Oversimplified Models MAXWELL MODEL Stress Relaxation σ(t)=σ0 exp( t/λ) − G(t)=G0 exp( t/λ) − Creep γ(t)=γ0(1 + t/λ) 0 0 J(t)=Js (1 + t/λ)=Js + t/η 2 G0(ωλ) Oscillatory Shear G (ω)=ωλG”(ω)= 0 1+(ωλ)2 The Maxwell Model is the simplest model of a VISCOELASTIC LIQUID. -

The Dynamics of Parallel-Plate and Cone–Plate Flows

The dynamics of parallel-plate and cone– plate flows Cite as: Phys. Fluids 33, 023102 (2021); https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0036980 Submitted: 10 November 2020 . Accepted: 09 December 2020 . Published Online: 18 February 2021 Anand U. Oza, and David C. Venerus COLLECTIONS This paper was selected as Featured Phys. Fluids 33, 023102 (2021); https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0036980 33, 023102 © 2021 Author(s). Physics of Fluids ARTICLE scitation.org/journal/phf The dynamics of parallel-plate and cone–plate flows Cite as: Phys. Fluids 33, 023102 (2021); doi: 10.1063/5.0036980 Submitted: 10 November 2020 . Accepted: 9 December 2020 . Published Online: 18 February 2021 Anand U. Oza1 and David C. Venerus2,a) AFFILIATIONS 1Department of Mathematical Sciences, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark, New Jersey 07102, USA 2Department of Chemical and Materials Engineering, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark, New Jersey 07102, USA a)Author to whom correspondence should be addressed: [email protected] ABSTRACT Rotational rheometers are the most commonly used devices to investigate the rheological behavior of liquids in shear flows. These devices are used to measure rheological properties of both Newtonian and non-Newtonian, or complex, fluids. Two of the most widely used geome- tries are flow between parallel plates and flow between a cone and a plate. A time-dependent rotation of the plate or cone is often used to study the time-dependent response of the fluid. In practice, the time dependence of the flow field is ignored, that is, a steady-state velocity field is assumed to exist throughout the measurement. -

Chapter 4 Flow in Channels

CHAPTER 4 FLOW IN CHANNELS INTRODUCTION 1 Flows in conduits or channels are of interest in science, engineering, and everyday life. Flows in closed conduits or channels, like pipes or air ducts, are entirely in contact with rigid boundaries. Most closed conduits in engineering applications are either circular or rectangular in cross section. Open-channel flows, on the other hand, are those whose boundaries are not entirely a solid and rigid material; the other part of the boundary of such flows may be another fluid, or nothing at all. Important open-channel flows are rivers, tidal currents, irrigation canals, or sheets of water running across the ground surface after a rain. 2 In both closed conduits and open channels, the shape and area of the cross section of the flow can change along the stream; such flows are said to be nonuniform. Flows are those that do not change in geometry or flow characteristics from cross section to cross section are said to be uniform. Remember that flows can be either steady (not changing with time) or unsteady (changing with time). In this chapter we will look at laminar and turbulent flows in conduits and channels. The emphasis in this chapter is on steady uniform flow in straight channels. That’s a simplification of flows in the natural world, in rivers and in the ocean, but it will reveal many fundamental aspects of those more complicated flows. The material in this chapter is applicable to a much broader class of flows, in pipes and conduits, as well; such matters are covered in standard textbooks on fluid dynamics. -

4 AN10 Abstracts

4 AN10 Abstracts IC1 IC4 On Dispersive Equations and Their Importance in Kinematics and Numerical Algebraic Geometry Mathematics Kinematics underlies applications ranging from the design Dispersive equations, like the Schr¨odinger equation for ex- and control of mechanical devices, especially robots, to the ample, have been used to model several wave phenom- biomechanical modelling of human motion. The major- ena with the distinct property that if no boundary con- ity of kinematic problems can be formulated as systems ditions are imposed then in time the wave spreads out of polynomial equations to be solved and so fall within spatially. In the last fifteen years this field has seen an the domain of algebraic geometry. While symbolic meth- incredible amount of new and sophisticated results proved ods from computer algebra have a role to play, numerical with the aid of mathematics coming from different fields: methods such as polynomial continuation that make strong Fourier analysis, differential and symplectic geometry, an- use of algebraic-geometric properties offer advantages in alytic number theory, and now also probability and a bit of efficiency and parallelizability. Although these methods, dynamical systems. In this talk it is my intention to present collectively called Numerical Algebraic Geometry, are ap- few simple, but still representative examples in which one plicable wherever polynomials arise, e.g., chemistry, biol- can see how these different kinds of mathematics are used ogy, statistics, and economics, this talk will concentrate on in this context. applications in mechanical engineering. A brief review of the main algorithms of the field will indicate their broad Gigliola Staffilani applicability. -

4: Non-Linear Viscoelasticity

Normal stress effects (Weissenberg et al. 1947) 4: non-linear viscoelasticity Main goals Ranges of viscoelasticity: the Deborah number - To develop constitutive models that can describe non-linear phenomena such as rod climbing - To use the equations in practical applications such as polymer processing and soft tissue mechanics A dissappointing point of view …… Three major topics: - Non-linear phenomena (time dependent) - Normal stress difference - Shear thinning - Extensional thickening - Most simple non-linear models - More accurate models Normal stress differences in shear Shear thinning - Data for a LDPE melt - Lines from the Kaye-Bernstein, Kearsley, Zapas (K-BKZ) model For small shear rates: Normal stress coefficients Shear thinning & time dependent viscosity Interrelations between shear functions For small shear rates: Cox-Merz rule Gleissle mirror rule Lodge-Meissner; after step shear: LDPE Steady shear (solid line) Cox Merz (open symbols) Gleissle mirro rule (solid points) Extensional thickening Extensional thickening Time-dependent, uniaxial uniaxial extensional viscosity extensional viscosity versus shear viscosity Non-linear behavior in uniaxial extensional viscosity is more sensitive to molecular archtecture than non-linear behavior in shear viscosity PS, HDPE: no branches 2 LDPE’s: branched, tree-like Stressing viscosities Second order fluid Simplest constitutive model that predicts a first normal stress difference: Upper convective derivative (definition): m = ½ uniaxial extension m = 1 biaxial extension Finger tensor: -

A Basic Introduction to Rheology

WHITEPAPER A Basic Introduction to Rheology RHEOLOGY AND Introduction VISCOSITY Rheometry refers to the experimental technique used to determine the rheological properties of materials; rheology being defined as the study of the flow and deformation of matter which describes the interrelation between force, deformation and time. The term rheology originates from the Greek words ‘rheo’ translating as ‘flow’ and ‘logia’ meaning ‘the study of’, although as from the definition above, rheology is as much about the deformation of solid-like materials as it is about the flow of liquid-like materials and in particular deals with the behavior of complex viscoelastic materials that show properties of both solids and liquids in response to force, deformation and time. There are a number of rheometric tests that can be performed on a rheometer to determine flow properties and viscoelastic properties of a material and it is often useful to deal with them separately. Hence for the first part of this introduction the focus will be on flow and viscosity and the tests that can be used to measure and describe the flow behavior of both simple and complex fluids. In the second part deformation and viscoelasticity will be discussed. Viscosity There are two basic types of flow, these being shear flow and extensional flow. In shear flow fluid components shear past one another while in extensional flow fluid component flowing away or towards from one other. The most common flow behavior and one that is most easily measured on a rotational rheometer or viscometer is shear flow and this viscosity introduction will focus on this behavior and how to measure it. -

Viscoelastic Shear Flow Over a Wavy Surface

J. Fluid Mech. (2016), vol. 801, pp. 392–429. c Cambridge University Press 2016 392 doi:10.1017/jfm.2016.455 Viscoelastic shear flow over a wavy surface Jacob Page1 and Tamer A. Zaki1,2, † 1Department of Mechanical Engineering, Imperial College, London SW7 2AZ, UK 2Department of Mechanical Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA (Received 7 January 2016; revised 11 May 2016; accepted 1 July 2016) A small-amplitude sinusoidal surface undulation on the lower wall of Couette flow induces a vorticity perturbation. Using linear analysis, this vorticity field is examined when the fluid is viscoelastic and contrasted to the Newtonian configuration. For strongly elastic Oldroyd-B fluids, the penetration of induced vorticity into the bulk can be classified using two dimensionless quantities: the ratios of (i) the channel depth and of (ii) the shear-waves’ critical layer depth to the wavelength of the surface roughness. In the shallow-elastic regime, where the roughness wavelength is larger than the channel depth and the critical layer is outside of the domain, the bulk flow response is a distortion of the tensioned streamlines to match the surface topography, and a constant perturbation vorticity fills the channel. This vorticity is significantly amplified in a thin solvent boundary layer at the upper wall. In the deep-elastic case, the critical layer is far from the wall and the perturbation vorticity decays exponentially with height. In the third, transcritical regime, the critical layer height is within a wavelength of the lower wall and a kinematic amplification mechanism generates vorticity in its vicinity. The analysis is extended to localized, Gaussian wall bumps using Fourier synthesis. -

Thermal Decomposition in 1D Shear Flow of Generalised Newtonian Fluids

Thermal Decomposition in 1D Shear Flow of Generalised Newtonian Fluids Adeleke Olusegun Bankole ([email protected]) African Institute for Mathematical Sciences (AIMS) Supervised by: Doctor Tirivanhu Chinyoka University of Cape Town, South Africa. 22 May 2009 Submitted in partial fulfillment of a postgraduate diploma at AIMS Abstract The effect of variable viscosity in a thermally decomposable generalised Newtonian fluids (GNF) sub- jected to unsteady 1D shear flow is investigated by direct numerical simulations. A numerical algorithm based on the semi-implicit finite-difference scheme is implemented in time and space using the temper- ature corrected Carreau model equation as the model for variable viscosity. The chemical kinetics is assumed to follow the Arrhenius rate equation; this reaction is assumed to be exothermic. Approximate (Numerical) and graphical results are presented for some parameters in the problem, thermal criticality conditions are also discussed. It is observed that increasing the non-Newtonian nature of the fluid helps to delay the onset of thermal runaway when compared to Newtonian nature of the fluid. Keywords: Thermally decomposable; Unsteady flow; Variable viscosity; Arrhenius chemical kinetics; Semi-implicit finite-difference scheme; Direct numerical simulations; Carreau model; Thermal runaway; Generalised Newtonian fluids(GNF) Declaration I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this essay is my original work, and that any work done by others or by myself previously has been acknowledged and referenced -

Surface Shear and Persistent Wave Groups

Surface Shear and Persistent Wave Groups Clifford Chafin Department of Physics, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695 ∗ September 15, 2021 Abstract We investigate the interaction of waves with surface flows by considering the full set of conserved quantities, subtle but important surface elevation changes induced by wave packets and by directly considering the necessary forces to prevent packet spreading in the deep water limit. Narrow surface shear flows are shown to exert strong localizing and stabilizing forces on wavepackets to maintain their strength and amplify their intensity even in the linear regime. Subtle packet scale nonlinear elevation changes from wave motion are crucial here and it suggest that popular notions of wave stress and action are naive. Quantitative bounds on the surface shear flow necessary to stabilize packets of any wave amplitude are given. One implication of this mechanism is that rogue wave stabilization must be due to a purely nonperturbative process. Rogue waves or \monster waves" are anomalously large waves that appear at sea and in very large lakes. Dismissed as sailors lore until the mid 1990's these waves appear in isolation or groups of three and may be a few times larger than the surrounding waves sometimes reaching over 30m. The damage and destruction these waves have delivered to the largest vessels and oil platforms is astounding. Aside from their scale, the striking feature of these waves is their frequency. They occur far more often than statistics would predict and their great difference in scale relative to the surrounding waves suggests some new mechanism is at work [8].