Differential Effectiveness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

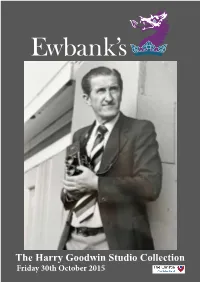

The Harry Goodwin Studio Collection

The Harry Goodwin Studio Collection Friday 30th October 2015 Chris Ewbank, FRICS ASFAV Andrew Ewbank, BA ASFAV Alastair McCrea, MA Senior partner Partner Partner, Entertainment, [email protected] [email protected] Memorabilia and Photography Specialist [email protected] John Snape, BA ASFAV Andrew Delve, MA ASFAV Tim Duggan, ASFAV Partner Partner Partner [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] THE HARRY GOODWIN STUDIO COLLECTION Surrey’s premier antique and fine art auction rooms THE HARRY GOODWIN STUDIO COLLECTION A lifetime photographing pop and sporting stars, over 20,000 images, most sold with full copyright SALE: Friday 30th October 2015 at 12noon VIEWING: Selected lots on view at the Manchester ARTZU Gallery: October 15th & 16th Full viewing at Ewbank’s Surrey Saleroom: Wednesday 28th October 10.00am - 5.00pm Thursday 29th October 10.00am - 5.00pm Morning of sale For the fully illustrated catalogue, to leave commission bids, and to register for Ewbank’s Live Internet Bidding please visit our new website www.ewbankauctions.co.uk The Burnt Common Auction Rooms London Road, Send, Surrey GU23 7LN Tel +44 (0)1483 223101 E-mail: [email protected] Buyers Premium 27% inclusive of VAT An unreserved auction with the hammer price for each lot sold going to the Christie NHS Foundation Trust MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY OF FINE ART AUCTIONEERS AND VALUERS FOUNDER MEMBERS OF THE ASSOCIATION OF ACCREDITED AUCTIONEERS http://twitter.com/EwbankAuctions www.facebook.com/Ewbanks1 INFORMATION FOR BUYERS 1. Introduction.The following informative notes are intended to assist Buyers, particularly those inexperienced or new to our salerooms. -

G3 August 2017

WWW.G3NEWSWIRE.COM/WWW.G3-247.COM International Gaming News / Knowledge / Statistics / Marketing Information / Digital and Print Association of Gaming Equipment Manufacturers Official MaGazine Global Games and Gaming Magazine August 2017 WWW.G3-247.COM WWW.G3NEWSWIRE.COM The Chilean city of Chillán is preparing to carry out definitive closures of neighbourhood casinos Chile P8 Vikings Casinos plans to begin construction in Sanary sur Mer in September and open in 2018 FranCe P18 Gaming Laboratories International Group acquires rival testing laboratory, NMi Gaming US P20 G3 Mar ket Update: GerMany Resorts World Manila has now resumed casino operations following the PAGCOR suspension PhiliPPineS P22 Calm befo re the storm SubScribe A mass ive s torm hangs abov e G erman stree ts whose at G3-247.com aftermath w ill dis appear a third of its gaming machines Read every G 3 m agazine, download every marke t report a nd muc h more... The latest magazine i s a vailable to digitally download via G 3-247.com or via the App Store Available on the Interact with G3 via... App Store and Google Play S tore Contents August 2017 SOUtH AMERICA EMEA Chile P8 UK P12 The municipal government of Chillán is The UK Gambling Commission is to bring into preparing to carry out a definitive closure of effect new measures aimed at protecting online the so-called ‘neighbourhood casinos’ players by granting them additional controls Samson House, ColomBia P8 SPain P14 Manchester Road, Manchester M29 7BR, Gaming regulator Coljuegos has awarded Melco International Development -

American Recorder Concertos

Roberto Sierra (b.1953) Prelude, Habanera and Perpetual Motion (2016)* Concerto for recorder and orchestra (live recording Tivoli July 1, 2018) Michala Petri, Tivoli Copenhagen Phil, conductor Alexander Shelley 1 Prelude .............................................................................................................. 4:11 2 Habanera ........................................................................................................... 4:19 3 Perpetual Motion ............................................................................................... 5:17 Steven Stucky (1949-2016) Etudes (2000) Concerto for recorder and orchestra Michala Petri, Danish National Symphony Orchestra, conductor Lan Shui 4 Scales ................................................................................................................ 3:07 5 Glides ................................................................................................................. 6:03 6 Arpeggios .......................................................................................................... 4:11 Anthony Newman (b.1941) Concerto for recorder, harpsichord & strings (2016)* AMERICAN Michala Petri, Anthony Newman, Nordic String Quartet 7 Toccata .............................................................................................................. 4:46 8 Devil’s Dance ..................................................................................................... 3:28 RECORDER 9 Lament .............................................................................................................. -

The University, on His Eigh Modern Literary Scene

~ ALUMNI/UNIVERSITY MAY 1957 VOL. XVIII NO.5 MAY VARSITY TENNIS, Union at Union. VARSITY GOLF, Brockport at MEN'S GLEE CLU B, 66th AN Rochester. NUAL HOME CONCERT. Strong VARSITY TENNIS, Buffalo at Auditorium, 8: 15 P. M. Admission Rochester. charge. VARSITY TRACK, Union at 13 VARSITY GOLF, Brockport at Union. Brockport. VARSITY BASEBALL, Union at VARSITY TENNIS, Alfred at Al Union. fred. 3 MEN'S GLEE CLUB CONCERT, 14 VARSITY GOLF, Niagara at Ni sponsored by UR Alumni Club agara. of Buffalo at Orchard Park High VARSITY BASEBALL, Hobart ct School. Hobart: VARSITY GOLF, Niagara at Rochester. 15 VARSITY GOLF, Hamilton at VARSITY BASEBALL, Rensselaer Rochester. at Rensselaer. VARSITY TENNIS, Hamilton at Rochester. 3-4 STAGERS PLAY, Chekov's "The Seagull." Strong Auditorium, 8: 15 16 ALL-UNIVERSITY SYMPHONY P. M. Admission charge. ORCHESTRA CONCERT with Editor student soloists. Strong Auditor CHARLES F. COLE, '25 4 MOVING-UP DAY CEREMO ium, 8:15 P. M. NIES. Eastman Ouadrangle, 2 VARSITY BASEBALL, Syracuse at P. M. Syracuse. Classnotes Editor VARSITY TENNIS, Niagara at DONALD A. PARRY, '51 Rochester. 17 VARSITY GOLF, Hobart at VARSITY TRACK, Brockport at Rochester. Brockport. ROCHESTER CLUB OF GREATER Art Director DETROIT, theater party, business VARSITY BASEBALL, Niagara at LEE D. ALDERMAN, '47 Rochester. meeting and election of officers. 7 VARSITY GOLF, Alfred at Alfred. 18 NEW YORK STATE TRACK VARSITY TENNIS, Niagara at MEET at Rochester. Published by The Uni Niagara. VARSITY TENNIS, Hobart at Rochester. versity of Rochester for ROCHESTER CLUB OF PHIL the Alumni Federation ADELPH lA, informal luncheon VARSITY BASEBALL, Hamilton meeting at the Hotel Adelphia. -

Subgroup VII. Fighters by Weightclass Series 1

Subgroup VII. Fighters by Weightclass Series 1. Champions and Contenders Box 1 Folder 1. Bantamweight: Luigi Camputaro Folder 2. Bantamweight: Jaime Garza Folder 3. Bantamweight: Bushy Graham, Scrapbook Folder 4. Bantamweight: Bushy Graham, Clippings Folder 5. Bantamweight: Alphonse Halimi Folder 6. Bantamweight: Harry Harris Folder 7. Bantamweight: Pete Herman Folder 8. Bantamweight: Rafael Herrera Folder 9. Bantamweight: Eder Jofre Folder 10. Bantamweight: Caspar Leon Folder 11. Bantamweight: Happy Lora Folder 12. Bantamweight: Joe Lynch Folder 13. Bantamweight: Eddie “Cannonball” Martin Folder 14. Bantamweight: Rodolfo Martinez Folder 15. Bantamweight: Pal Moore Folder 16. Bantamweight: Owen Moran Folder 17. Bantamweight: Kid Murphy Box 2 Folder 1. Bantamweight: Jimmy Navarro Folder 2. Bantamweight: Frankie Neil Folder 3. Bantamweight: Rafael Orono Folder 4. Bantamweight: Manuel Ortiz Folder 5. Bantamweight: Georgie Pace Folder 6. Bantamweight: Harold Petty Folder 7. Bantamweight: Jesus Pimental Folder 8. Bantamweight: Enrique Pinder Folder 9. Bantamweight: Lupe Pintor Folder 10. Bantamweight: Leo Randolph Folder 11. Bantamweight: Lionel Rose Folder 12. Bantamweight: Charley Phil Rosenberg Folder 13. Bantamweight: Alan Rudkin Folder 14. Bantamweight: Lou Salica Folder 15. Bantamweight: Richie Sandoval Folder 16. Bantamweight: Julian Solis Folder 17. Bantamweight: Arnold Taylor Folder 18. Bantamweight: Bud Taylor Folder 19. Bantamweight: Vic Toweel Folder 20. Bantamweight: Cardeno Ulloa Folder 21. Bantamweight: Jimmy Walsh Folder 22. Bantamweight: Kid Williams Folder 23. Bantamweight: Johnny Yasui Folder 24. Bantamweight: Alfonse Zamora Folder 25. Bantamweight: Carlos Zarate Box 3 1 Folder 1. Featherweight: Miscellaneous Fighters Folder 2. Featherweight: Joey Archibald Folder 3. Featherweight: Baby Arizimendi Folder 4. Featherweight: Abe Attell, photocopied clippings Folder 5. Featherweight: Abe Attell, newspaper clippings Folder 6.