Doctoral Dissertation Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Program

2 American 0 E ducational 0 S tudies 7 A ssociation ANNUAL CONFERENCE October 24-28, 2007 Joint Meeting with the History of Education Society THE MARRIOTT HOTEL AT KEY CENTER CLEVELAND, OHIO American Educational Studies Association ANNUAL CONFERENCE October 24-28, 2007 Joint Meeting with the History of Education Society THE MARRIOTT HOTEL AT KEY CENTER CLEVELAND, OHIO _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ AESA The role of AESA is to provide a cross-disciplinary forum in which scholars can gather to exchange and debate theoretical issues and empirical research that addresses the social context of education. The cross-disciplinary commitment of the organization creates a landscape for the discussion of a broad range of issues involving multiculturalism and diversity, globalization, the politics of education, and pedagogical practice. _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ For further information about the association, please visit our website: www.educationalstudies.org. AESA 2007 ANNUAL CONFERENCE _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ AESA Officers Past President, Steve Tozer, University of Illinois at Chicago President, Dennis Carlson, Miami University President-Elect and Program Chair, Susan Franzosa, Fairfield University Vice President, Kathy Hytten, -

Index of Thinking Volumes

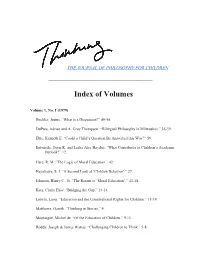

THE JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY FOR CHILDREN __________________________________________________ Index of Volumes Volume 1, No. 1 (1979) Buchler, Justus. “What is a Discussion?” 4954. DuPuis, Adrian and A. Gray Thompson. “Bilingual Philosophy in Milwaukee.” 3539. Eble, Kenneth E. “Could a Child’s Question Be Answered this Way?” 59. Entwistle, Doris R. and Leslie Alec Hayduc. “What Contributes to Children’s Academic Outlook?” 12. Hare, R. M. “The Logic of Moral Education.” 42. Hayakawa, S. I. “A Second Look at ‘Childish Behavior’.” 27. Johnson, Henry C., Jr. “The Return to ‘Moral Education’.” 4148. Katz, Claire Elise. “Bridging the Gap,” 1314. Letwin, Leon. “Education and the Constitutional Rights for Children.” 1119. Matthews, Gareth. “Thinking in Stories.” 4. Montaigne, Michel de. “Of the Education of Children.” 911. Roddy, Joseph & James Watras. “Challenging Children to Think.” 58. Simon, Charlann. “Philosophy for Students with Learning Disabilities.” 2133. Wagner, Paul A.“Philosophy, Children, and ‘Doing Science’.” 5557. Worsfold, Victor L. “What Claims Can Children Make?” 13. Volume 1, No. 2 (1979) Aman, Kenneth and Sister Anna Maria Hartman. “Philosophy for Children in a SpanishSpeaking Contest.” 410. Barr, Donald. “How Important are Categories for Children.” 11. Berman, Ronald. “On Writing Good.” 12. Brent, Frances. “Philosophy and the MiddleSchool Student.” 39. Chesternon, Gilbert Keith. “The Ethics of Elfland.” 1320. Dostoevsky, Fedor. “Ghost and Eternity.” 27. Education Commission of the States. “The Higher Level Skills: Tomorrow’s ‘Basics’.” 11. Freire, Paulo. “Education Through Dialogue.” 11. Gosse, Edmund. “Untitled from Father and Son.” 4346. Hullfish, H. Gordon. “Thinking and Meaning.” 12. -

The Gendered Character of Higher Education

PPMARTIN 12/05/97 3:35 PM ARTICLES BOUND FOR THE PROMISED LAND: THE GENDERED CHARACTER OF HIGHER EDUCATION * JANE ROLAND MARTIN Given the history of women and higher education in the United States, the fact that fifty percent or more of undergraduates are now female is cause for cele- bration,1 but not complacency. This article discusses the chilly coeducational class- room climate2 for women in institutions of higher education,3 the inadequate repre- sentation of women in the professoriate,4 and the relative silences about and misrepresentations of women in higher education’s curriculum.5 The goal is not to reiterate what is already well known. Rather, the emphasis is on the importance of seeing what are often considered to be quite separate problems concerning women in higher education as related to one another and of treating them as forming part of a larger pattern. To this end, I will propose a new way of thinking about women and higher education rooted in immigrant imagery.6 One strength of this reorien- tation of perception and thought is that it encourages the pulling together of what have been seen as unrelated phenomena. Another is that it points to the valuable distinction between assimilation and acculturation. In the concluding section, I will list some of the benefits of an acculturationist stance not only for girls and women, but also for the nation.7 I. THE IMMIGRANT HYPOTHESIS Not quite sixty years ago Virginia Woolf invited women to stand on the bridge connecting two worlds—private and public, home and professions, women’s and men’s—and “fix our eyes upon the procession—the procession of * Professor of Philosophy Emerita, University of Massachusetts, Boston; Visiting Professor of Education, Harvard University, 1996-97. -

The Place of Reason in Education

THE PLACE OF REASON IN EDUCATION By Bertram Bondman OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS THE PLACE OF REASON IN EDUCATION By Bertram Bandman Educational philosophies frequently col lide with some violence but without mak ing much impact on the educational com munity and on its practices and policies. That such collisions are inconclusive is seen to result from the absence of accept able criteria for rationally judging be tween conflicting educational proposals. Mr. Bandman seeks to demonstrate the relevance of philosophy to education by undertaking a philosophical examination of the crucial question in education "What should be taught?" His purpose is to de termine what, if anything, qualifies as a rational argument in helping us to answer this fundamental question. In his examination of the scope and limits of reason in education, Mr. Band- man attempts to locate pertinent canons of criticism by which an educational argu ment may be assessed, on the assumption that it is quite possible to deal rationally with arguments that are employed in edu cational controversy. He imposes no single philosophical standard for making such an assessment, and though he offers criti cism of metaphysical and moral assump tions in education, he neither accepts nor rejects any philosophical doctrine in toto. An evaluative argument in education, Mr. Bandman finds, is one that may be used either as a quarrel or debate, as a proof or demonstration, or as a set of (Continued on back flap) Studies in Educational Theory of the John Dewey Society NUMBER 4 The Place -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College’S Academic Counselor Abby

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SHAREOK repository UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE EDUCATIONAL RESPONSES TO THE CANCER INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX PINK WAR MACHINE: THEORIZING GENDER INSUBORDINATION FROM AUTOBIOGRAPHIES OF BREAST AND GYNECOLOGICAL CANCERS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillmEnt of the requiremEnts for the DEgreE of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By JULIE MICHELLE KOGAN DAVIS Norman, Oklahoma 2019 EDUCATIONAL RESPONSES TO THE CANCER INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX PINK WAR MACHINE: THEORIZING GENDER INSUBORDINATION FROM AUTOBIOGRAPHIES OF BREAST AND GYNECOLOGICAL CANCERS A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP AND POLICY STUDIES BY Dr. Susan Laird, Chair Dr. Thomas J. Burns Dr. Joan K. Smith Dr. Siduri HaslErig Dr. William Frick Dr. Jill Irvine © Copyright by JULIE MICHELLE KOGAN DAVIS 2019 All Rights ResErved. iv Dedication “Illness affects the body, YEt remains apart. It cannot reach the spirit Or touch the human heart. Love HEals!” –Robert E. Kogan, “January 6,” Love Heals: 31 Days of Loving You and Other Poems To Robert Earl Kogan, poet and dreamEr, and Linda Beth Kogan, who kept him grounded. v Acknowledgements There are many peoplE I neEd to thank. Foremost, Dr. Susan Laird whosE patiEncE and mEntorship haVE shown mE what tEaching with love is. Dr. Laird has sEEn mE through raising threE children, fostEred my intEllEctual passions, and beEn there for mE through joys and sorrows. Thank you will neVEr be enough. Dr. Thomas Burns I must thank for unwaVEring support, cups of hot tEa on cold days, spiritually renewing and challEnging conversations that pointEd mE in new directions, and, when neEded, a pocketful of HErshey’s kissEs. -

Fifty Major Thinkers on Education: from Confucius to Dewey/Edited by Joy A

FIFTY MAJOR THINKERS ON EDUCATION In this unique work some of today’s greatest educators present concise, accessible summaries of the great educators of the past. Covering a time-span from 500 BC to the early twentieth century, the book includes profiles of: • Augustine • Dewey • Erasmus • Gandhi • Kant • Montessori • Plato • Rousseau • Steiner • Wollstonecraft Each essay gives key biographical information, an outline of the individual’s principal achievements and activities, an assessment of their impact and influence, a list of their major writings and suggested further reading. Together with Fifty Modern Thinkers on Education, this book provides a unique reference guide for all students of education. Joy A.Palmer is Professor of Education and Pro-Vice-Chancellor at the University of Durham, England. She is Vice-President of the National Association for Environmental Education and a member of the IUCN Commission on Education and Communication. Advisory Editors: Liora Bresler is Professor of Curriculum and Instruction at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. David E.Cooper is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Durham. ROUTLEDGE KEY GUIDES Routledge Key Guides are accessible, informative and lucid handbooks, which define and discuss the central concepts, thinkers and debates in a broad range of academic disciplines. All are written by noted experts in their respective subjects. Clear, concise exposition of complex and stimulating issues and ideas make Routledge Key Guides the ultimate reference resources for students, -

Education Feminism

Introduction Barbara J. Thayer-Bacon, PhD University of Tennessee, Knoxville The Background In 1994 Lynda Stone published an outstanding collection of feminist writers who were writing about feminist theory and pedagogy in connection to educational theory and practice.1 Right around the same time, Barbara Thayer-Bacon developed a “Feminist Epistemology and Education” course that she began teaching at Bowling Green State University (BGSU). This course employed Belenky, Clinchy, Goldberger, and Tarule’s Women’s Ways of Knowing as the starting point, continuing with the articles and essays of current work in feminist epistemology (which eventually evolved to using Thayer-Bacon’s own book, Relational “(e)pistemologies,”) and ending with Lynda Stone’s edited book, The Education Feminism Reader.2 The course was cross-listed with Women’s Studies and Educational Foundations and Inquiry, and offered graduate students a possible course toward a graduate certificate in Women’s Studies. Students from various programs across the campus such as American Studies and Communications Studies took the course and found the connections between feminist theory and educational theory important and exciting. When Thayer-Bacon was hired by the University of Tennessee (UT) in 2000, she found that there was a shortage of course options available to graduate students who wanted a certificate in Women’s Studies, which was offered at UT as well. This was espe- cially the case for students earning degrees in the College of Education. She introduced her “Feminist Epistemology and Education” course (CSE 609) to the UT curriculum, and when another feminist scholar joined the Cultural Studies in Education program, the title of the course was broadened to “Feminist Theory and Education” so either one of us could teach CSE 609, and each offer our own unique course design. -

Philosophy of Education (Dimensions of Personality), by Nel Noddings.Pdf

Philosophy of Education Nel Noddings STANFORD UNIVERSITY 1 Westview Press A Member of Perseus Books, L.L.C. Dimensions of Philosophy Series All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Copyright © 1998 by Westview Press, A Member of Perseus Books, L.L.C. Published in 1995 in the United States of America by Westview Press, Inc., 5500 Central Avenue, Boulder, Colorado 80301- 2877, and in the United Kingdom by Westview Press, 12 Hid's Copse Road, Cumnor Hill, Oxford OX2 9JJ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Noddings, Nel Philosophy of education / Nel Noddings p. cm. -- (Dimensions of philosophy series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8133-8429-X. -- ISBN 0- 8133-8430-3 (pbk) 1. Education--Philosophy. I. Title. II. Series. LB15. 7. N63 1995 370′ . 1--dc20 95-8820 CIP Printed and bound in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39. 48-1984. 10 9 8 7 6 2 Acknowledgments 6 Introduction ..........................................................................................................................................................7 1 Philosophy of Education Before the Twentieth Century.........................................................................9 -

Download Program

American Educational Studies Association 2002 Annual Meeting October 30 - November 3, 2002 Omni William Penn Hotel Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Meeting Cooperatively with the HISTORY OF EDUCATION SOCIETY Pittsburgh Marriott City Center Hotel Direction: Exit the Omni William Penn onto Grant Street and look for the HES hotel, the Pittsburgh Marriott City Center, across Steel Plaza and up the hill UNIVERSITY COUNCIL FOR EDUCATIONAL ADMINISTRATION Hilton Pittsburgh Hotel Direction: Exit the Omni William Penn onto Grant Street, enter the Steel Plaza “T” station, and take the free subway ride to Gateway Center. After walking up the stairs of the “T” station at Gateway Center, bear slightly right, walk down Liberty Avenue toward the Golden Triangle, and look for the UCEA hotel, the Hilton Pittsburgh, at the intersection of Liberty Avenue and Commonwealth Place. MIDWEST/NORTHEAST REGIONAL COMPARATIVE AND INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION SOCIETY Omni William Penn Hotel and University of Pittsburgh Direction: The society will meet with AESA in the Omni William Penn on Thursday, October 31, and Friday, November 1. MW/NE CIES sessions will move to the campus of the University of Pittsburgh in the Oakland area of the city on Saturday, November 2, and Sunday, November 3. Ask for directions at the William Penn concierge’s desk. MEXICO CITY 2003! October 29 – November 2 Sheraton Maria Isabel Hotel and Towers Founded in 1525, Mexico City is the oldest capital in the Americas. The city will offer AESA members the largest number of museums and the fourth largest number of theatres in the world as well as many archaeological and historical sites.