What's in Two Names?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

12610 Record Name

Record 12610 Name: apl 2018 withdrawals Note: Call Number Barcode Author Title Physical Cost Date Created Condition 649.133 Coh 33411830134011 Cohen-Sandler, Roni. "Trust me, Mom--everyone else is average/noncir 24.95 3/21/2002 going!" : the new rules for culating mothering adolescent girls 973.917 Hoy 33411830035390 Hoyt, Ray. "We can take it" : a short story of average/noncir 10.00 3/20/2000 the C.C.C. culating 920 Bec 33410420939912 Beckner, Chrisanne. 100 African-Americans who average/noncir 7.95 9/28/1996 shaped American history culating 618.3 Gei 33411830342770 Geil, Patti Bazel. 101 tips for a healthy pregnancy average/noncir 14.95 12/29/2004 with diabetes culating AudCD 33411830500542 Menzies, Gavin. 1434 [CD sound recording] : the average/noncir 16.47 12/4/2008 945.05 Men year a magnificent Chinese fleet culating sailed to Italy and ignited the Renaissance Mys Pat 201507010112 Patterson, James, 1947- 15th affair average/noncir 14.65 6/29/2016 author. culating Mys Pat 1601140181 Patterson, James, 1947- 16th seduction average/noncir 14.65 5/11/2017 author. culating 641.5 Sch 33410421099153 Schur, Sylvia. 365 easy low-calorie recipes average/noncir 12.95 3/9/1998 culating Fic Oji 33411830239679 Ojikutu, Bayo. 47th Street Black : a novel average/noncir 12.95 10/10/2003 culating Fic Rei 33411830472981 Reilly, Matthew. 7 deadly wonders : a novel average/noncir 23.00 12/21/2005 culating 813 Har 33411920742467 Harte, Bret, 1836-1902. 9 sketches average/noncir 18.95 10/17/2001 culating J 320.473 33411830324075 Kowalski, Kathiann M., A balancing act : a look at checks average/noncir 25.00 2/4/2005 Kow 1955- and balances culating 332.7 Boo 33410420636773 Boothe, Ben B. -

Cassette Books, CMLS,P.O

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 319 210 EC 230 900 TITLE Cassette ,looks. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. PUB DATE 8E) NOTE 422p. AVAILABLE FROMCassette Books, CMLS,P.O. Box 9150, M(tabourne, FL 32902-9150. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) --- Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adults; *Audiotape Recordings; *Blindness; Books; *Physical Disabilities; Secondary Education; *Talking Books ABSTRACT This catalog lists cassette books produced by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped during 1989. Books are listed alphabetically within subject categories ander nonfiction and fiction headings. Nonfiction categories include: animals and wildlife, the arts, bestsellers, biography, blindness and physical handicaps, business andeconomics, career and job training, communication arts, consumerism, cooking and food, crime, diet and nutrition, education, government and politics, hobbies, humor, journalism and the media, literature, marriage and family, medicine and health, music, occult, philosophy, poetry, psychology, religion and inspiration, science and technology, social science, space, sports and recreation, stage and screen, traveland adventure, United States history, war, the West, women, and world history. Fiction categories includer adventure, bestsellers, classics, contemporary fiction, detective and mystery, espionage, family, fantasy, gothic, historical fiction, -

Illiteracy: the Ultimate Crime

ILLITERACY: THE ULTIMATE CRIME Ana de Brito Politecnico do Porto, Portugal The iss ue of reading ha s a privileged positi on in Ruth's Rendell's novels. In several, the uses of reading and its effects are disc ussed in some detail. But so are the uses of not reading and the non-read ers. The non-readers in Rendell's novels also have a special position . The murderer in The Hou se of Stairs is a non-reader but even so she is influenced by w hat other peopl e read. Non-readers often share the view that reading is an tisocial or that it is difficult to und er stand th e fascination that book s, those "small, flattish boxes"l have for their read ers. But Burd en is the most notoriou s non -reader w ho co mes to mind. His evolu tio n is ske tched throughout the Inspector Wexford mysteries. In From Doom with Death (1964) he thinks that it is not healthy to read, but Wexford lends him The Oxford Book of Victorian Verse for his bedtime reading, and the effects on his turn of phrase are immediate: 'I suppose the others could have been just-well , playthings as it we re, and Mrs. P. a life-long love.' 'Christ!', Wexford roared . 'I should never have let you read that book. Playthings, life-long love! You make me puke' (p. 125). In the 1970 novel A Cuiltlj Thing Surprised, Burden still feels embarrassed by his superior's "ted ious bookishness", and knows th e difference between fiction and real life.Pro us tia n or Shakespearean references are lost on Burden in No More Dying Fragmentos vol. -

Core Collection Adult Fiction 2017

NAME TITLE Peter Ackroyd Hawksmoor Richard Adams Watership Down Douglas Adams Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy Chimamanda Adichie Half of a Yellow Sun Chimamanda Adichie Purple Hibiscus Ryunosuke Akutagawa Rashomon Mitch Albom The Five People You Meet in Heaven Louisa May Alcott Little Women Monica Ali Brick Lane Isabel Allende House of the Spirits Margery Allingham The Tiger in the Smoke Eric Ambler Journey into Fear Kingsley Amis Lucky Jim Kingsley Amis The Old Devils Martin Amis Money Martin Amis London Fields Jeffrey Archer First Among Equals Jeffrey Archer Not a Penny More Not a Penny Less Jake Arnott The Long Firm Isaac Asimov I, Robot Kate Atkinson Behind the Scenes at the Museum Margaret Atwood Cats Eye Margaret Atwood Handmaid’s Tale Jean Auel Clan of the Cave Bear Jane Austen Sense and Sensibility Jane Austen Pride and Prejudice Jane Austen Mansfield Park Jane Austen Emma Beryl Bainbridge An Awfully Big Big Adventure Beryl Bainbridge Master Georgie Dorothy Baker Young Man with a Horn David Baldacci Absolute Power James Baldwin Go Tell it on the Mountain James Baldwin Giovanni’s Room J G Ballard Empire of the Sun Balzac Eugenie Grandet Balzac Old Goriot Balzac The Black Sheep Iain Banks The Wasp Factory Iain Banks The Crow Road Julian Barnes Staring at the Sun Julian Barnes Flaubert’s Parrot Pat Barker Regeneration Pat Barker Eye in the Door Pat Barker Ghost Road Sebastian Barry The Secret Scripture Stan Barstow A Kind of Loving H E Bates Love for Lydia H E Bates Fair stood the Wind for France Arnold Bennett Anna of the Five Towns E F Benson Queen Lucia E F Benson Mapp and Lucia Mark Billingham Scaredy Cat Mark Billingham Sleepy head Maeve Binchy Light a Penny Candle Maeve Binchy Echoes R D Blackmore Lorna Doone Boccaccio The Decameron Paul Bowles The Sheltering Sky William Boyd Restless William Boyd Good Man in Africa Malcolm Bradbury The History Man Ray Bradbury Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury The Illustrated Man Ray Bradbury Something Wicked This Way Comes M. -

Ruth Rendell/Barbara Vine: Social Thriller, Ethnicity and Englishness

Ruth Rendell/Barbara Vine: Social Thriller, Ethnicity and Englishness Lidia Kyzlinková Masaryk University, Brno Ruth Rendell is viewed as one of the main representatives of the British psychological crime novel today, however, apart from her interest in the individual characters’ psyches she purposefully covers a number of fundamental social phenomena existing in contemporary Britain.1 I select three of Rendell’s well-known crime thrillers (one written under her pseudonym of Barbara Vine) that are deeply disturbing from the social viewpoint. All three of them are her non-Wexford mysteries, i.e. without the so-called ‘Great Detective’ (Chief Inspector Wexford), where the police factor is considerably diminished and which I term socio-psychological, or social thrillers: A Demon In My View (Rendell, 1976), A Fatal Inversion (Vine, 1987), and The Crocodile Bird (Rendell, 1993). The novels clearly link the conservative cultural modes of the Victorian past with contemporary social experience of Englishness, where ethnicity and identity constitute the most significant issues. Rendell’s positive obsession with the English language and literature through which she intensifies the specific Englishness of her writing is gradually becoming more and more visible in each of the decade in question: With The Crocodile Bird this aspect forms a crucial part of the plot. The issues of class and ethnicity may still be regarded as the greatest sources of division in contemporary British society, and both of these are closely related to the central theme of the first two novels analysed. In A Fatal Inversion, which deals with both the 1970s and 1980s, race, class and immigration seem fundamentally significant. -

Appendix A: the Complete Detective and Crime Novels of the Six Authors

Appendix A: The Complete Detective and Crime Novels of the Six Authors Agatha Christie (1890–1976) Hercule Poirot The Mysterious Affair at Styles (UK, London: Lane, 1920; US, New York: Dodd Mead, 1927). The Murder on the Links (UK, London: Lane, 1923; US, New York: Lane, 1923). The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (UK, London: Collins, 1926; US, New York: Dodd Mead, 1926). The Big Four (UK, London: Collins, 1927; US, New York: Dodd Mead, 1927). The Mystery of the Blue Train (UK, London: Collins, 1928; US, New York: Collins, 1928). Peril at End House (UK, London: Collins, 1932; US, New York: Dodd Mead, 1932). Lord Edgware Dies (UK, London: Collins, 1933) as Thirteen at Dinner (US, New York: Dodd Mead, 1933) Murder on the Orient Express (UK, London: Collins, 1934) as Murder on the Calais Coach (US, New York: Dodd Mead, 1934). Death in the Clouds (UK, London: Collins, 1935) as Death in the Air (US, New York: Dodd Mead, 1935). The ABC Murders (UK, London: Collins, 1936; US, New York: Dodd Mead, 1936) as The Alphabet Murders (US, New York: Pocket Books, 1966). Cards on the Table (UK, London: Collins, 1936; US, New York: Dodd Mead, 1937). Murder in Mesopotamia (UK, London: Collins, 1936; US, New York: Dodd Mead, 1936). Death on the Nile (UK, London: Collins, 1937; US, New York: Dodd Mead, 1938). Dumb Witness (UK, London: Collins, 1937) as Poirot Loses a Client (US, New York: Dodd Mead, 1937). Appointment with Death (UK, London: Collins, 1938; US, New York: Dodd Mead, 1938). Hercule Poirot’s Christmas (UK, London: Collins, 1938) as Murder for Christmas (US, New York: Dodd Mead, 1939) as A Holiday for Murder (US, New York: Avon, 1947). -

Bio-Bibliographie PDF, 157,3 KB

Bio-Bibliographie Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Alle Angaben ohne Gewähr. © Diogenes Verlag AG www.diogenes.ch e-mail: [email protected] Diogenes Bio-Bibliographie Barbara Vine Barbara Vine (Pseudonym von Ruth Rendell), geboren 1930, lebte bis zu ihrem Tod am 2. Mai 2015 in London. Ihre Bücher erhielten zahlreiche Auszeichnungen. Mit König Salomons Teppich wurde zum vierten Mal – eine Rekordzahl – ein Werk von ihr mit dem Gold Dagger Award der Crime Writers’ Association ausgezeichnet, 1996 erhielt sie von der Queen den Ehrentitel Commander of the British Empire und 1997 den Grand Master Award der Mystery Writers of America für das Gesamtwerk. Sie wurde auf Vorschlag von Tony Blair geadelt und 1997 ins House of Lords berufen. Werke A Dark-Adapted Eye · Roman. 1986 Die im Dunkeln sieht man doch Aus dem Englischen von Renate Orth-Guttmann Zürich: Diogenes, 1988; Taschenbuchausgabe ebd., 1989 (detebe 21826); eBook ebd., 2013 (60121); Neuausgabe Taschenbuch ebd., 2018 (detebe 24468) A Fatal Inversion · Roman. 1987 Es scheint die Sonne noch so schön Aus dem Englischen von Renate Orth-Guttmann Zürich: Diogenes, 1989; Taschenbuchausgabe ebd., 1991 (detebe 22417); eBook ebd., 2013 (60113) Diogenes · Bio-Bibliographie Barbara Vine Seite 2 The House of Stairs · Roman. 1988 Das Haus der Stufen Aus dem Englischen von Renate Orth-Guttmann Zürich: Diogenes, 1990; Taschenbuchausgabe ebd., 1993 (detebe 22582); eBook ebd., 2013 (60120) Gallowglass · Roman. 1990 Liebesbeweise Aus dem Englischen von Renate Orth-Guttmann Zürich: Diogenes, 1991; Taschenbuchausgabe ebd., 1993 (detebe 22583); eBook ebd., 2013 (60114); neue Taschenbuchausgabe ebd., 2019 (detebe 24493) King Solomon’s Carpet · Roman. 1991 König Salomons Teppich Aus dem Englischen von Renate Orth-Guttmann Zürich: Diogenes, 1993; Taschenbuchausgabe ebd., 1994 (detebe 22736); eBook ebd., 2013 (60124) Asta’s Book · Roman. -

The Works of Ruth Rendell

The Works of Ruth Rendell Chief Inspector Wexford (24 novels, 2 short story collections) From Doon with Death (1964) questions asked, and for five bucks a man could have three hours of undisturbed, illicit lovemaking. There is nothing extraordinary about Margaret Parsons, a timid housewife in the Then one evening a man with a knife turned the love nest into a quiet town of Kingsmarkham, a woman death chamber. The carpet was soaked with blood -- but where devoted to her garden, her kitchen, her was the corpse? husband. Except that Margaret Parsons is dead, brutally strangled, her body Meanwhile, Anita Margolis had vanished – along with the abandoned in the nearby woods. bundle of cash she’d had in her pocket. There was no body, no crime - nothing more concrete than an anonymous letter and Who would kill someone with nothing to hide? Inspector the intriguing name of Smith. According to headquarters, it Wexford, the formidable chief of police, feels baffled -- until he wasn't to be considered a murder enquiry at all. Chief Inspector discovers Margaret's dark secret: a trove of rare books, each Wexford, however, had other ideas. volume breathlessly inscribed by a passionate lover identified only as Doon. As Wexford delves deeper into both Mrs. The Best Man to Die (1969) Parsons’ past and the wary community circling round her memory like wolves, the case builds with relentless momentum Who could have suspected that the exciting to a surprise finale as clever as it is blindsiding. stag party for the groom would be the prelude to the murder of his close friend Sins of the Fathers (1967) a.k.a. -

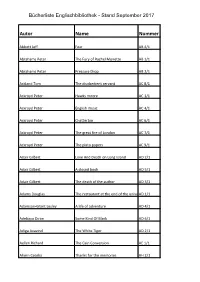

Autor Name Nummer

Bücherliste Englischbibliothek - Stand September 2017 Autor Name Nummer Abbott Jeff Fear AB 4/1 Abrahams Peter The Fury of Rachel Monette AB 1/1 Abrahams Peter Pressure Drop AB 2/1 Ackland Tom The disobedient servant AC 8/1 Ackroyd Peter Hawks moore AC 1/1 Ackroyd Peter English music AC 4/1 Ackroyd Peter Chatterton AC 6/1 Ackroyd Peter The great fire of London AC 7/1 Ackroyd Peter The plato papers AC 9/1 Adair Gilbert Love And Death on Long Island AD 2/1 Adair Gilbert A closed book AD 5/1 Adair Gilbert The death of the author AD 3/1 Adams Douglas The restaurant at the end of the universeAD 1/1 Adamson-Grant Lesley A life of adventure AD 4/1 Adebayo Diran Some Kind Of Black AD 6/1 Adiga Avavind The White Tiger AD 2/1 Aellen Richard The Cain Conversion AE 1/1 Ahern Cecelia Thanks for the memories AH 2/1 Aird Catherine Henrietta Who? AI 1/1 Alan Sillitoe Saturday Night and Sunday Morning SL 3/7 Albeury Ted The twentieth day of january AL 10/1 Albeury Ted Moscow quadrille Al 19/1 Albeury Ted The Lantern network AL 6/2 Albeury Ted The Lantern network AL 6/3 Albeury Ted The reaper Al 8/1 Albom Mitch tuesdays with Morrie AL 27/1 Albom Mitch For ond more day AL 29/1 Albom Mitch for one more day AL 29/2 Albom Mitch The five people you meet in heaven Al 30/1 Alcott Louisa M. -

1000 Novels Everyone Must Read

Bouvard et Pécuchet by Gustave Flaubert 1000 novels everyone must Towards the End of the Morning by Michael Frayn read: the definitive list The Polygots by William Gerhardie Cold Comfort Farm by Stella Gibbons Dead Souls by Nikolai Gogol theguardian.com, Friday 23 January 2009 Oblomov by Ivan Goncharov 10.23 EST The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame Brewster's Millions by Richard Greaves (George Barr Selected by the Guardian's Review team and a panel McCutcheon) of expert judges, this list includes only novels – no Squire Haggard's Journal by Michael Green memoirs, no short stories, no long poems – from any Our Man in Havana by Graham Greene decade and in any language. Originally published in Travels with My Aunt by Graham Greene thematic supplements – love, crime, comedy, family Diary of a Nobody by George Grossmith and self, state of the nation, science fiction and The Little World of Don Camillo by Giovanni fantasy, war and travel – they appear here for the first Guareschi time in a single list. The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time by Mark Haddon Catch-22 by Joseph Heller Comedy Mr Blandings Builds His Dream House by Eric Hodgkins Lucky Jim by Kingsley Amis High Fidelity by Nick Hornby Money by Martin Amis I Served the King of England by Bohumil Hrabal The Information by Martin Amis The Lecturer's Tale by James Hynes The Bottle Factory Outing by Beryl Bainbridge Mr Norris Changes Trains by Christopher Isherwood According to Queeney by Beryl Bainbridge The Mighty Walzer Howard by Jacobson Flaubert's Parrot by Julian Barnes Pictures from an Institution by Randall Jarrell A History of the World in 10 1/2 Chapters by Julian Three Men in a Boat by Jerome K Jerome Barnes Finnegans Wake by James Joyce Augustus Carp, Esq. -

Psychological Suspense

Psychological Suspense Ruth Rendell and Minette Walters have long been famous for psychological suspense novels depicting sociological issues such as domestic abuse, inequality, and homosexuality. These novels often depict the darker side of the protagonists psyche, and the effect of society on the human mind. There are now several writers penning works in this genre. Abrahams, Peter. Abrahams is Stephen King‟s favorite suspense writer. Joyce Carol Oates described Abrahams novels as “gratifyingly attentive to psychological detail, richly atmospheric, layered in ambiguity.” Series Echo Falls 1. Down the Rabbit Hole (2005) 2. Behind the Curtain (2006) 3. Into the Dark (2008) Novels The Fury of Rachel Monette (1980) Tongues of Fire (1982) Red Message (1986) Hard Rain (1988) Pressure Drop (1989) Revolution Number 9 (1992) Lights Out (1994) The Fan (1995) A Perfect Crime (1998) Crying Wolf (2000) Last of the Dixie Heroes (2001) The Tutor (2002) Their Wildest Dreams (2003) Oblivion (2005) End of Story (2006) Nerve Damage (2007) Delusion (2008) Reality Check (2009) Bullet Point (2010) Alvtegen, Karin. Karin Alvtegen, b. 1965, is one of Scandinavia's most widely read authors. Recognized for her artful characters and psychological thrillers, her books are best sellers worldwide. Missing (2003) Guilt (2004) Betrayal (2005) Shame (2006) Shadow (2009) 1 Anders, Donna. Anders is known for strong female protagonists, often single mothers overcoming terrifying situations. Novels Ketti (1991) Mari (1991) Sun of the Morning (1991) Paradise Moon (1992) The Flower Man (1995) Another Life (1998) Dead Silence (2000) In All the Wrong Places (2002) Night Stalker (2003) Afraid of the Dark (2004) Death Waits for You (2006) Sketching Evil (2007) Armstrong, Charlotte. -

Ruth Rendell Author

Ruth Rendell Author Since her first novel FROM DOON WITH DEATH, published in 1964, Ruth Rendell has won many awards, including the Crime Writers' Association Gold Dagger for 1976's best crime novel with A DEMON IN MY VIEW, and the Arts Council National Book Award, genre fiction, for LAKE OF DARKNESS in 1980. In 1985 Ruth Rendell received the Silver Dagger for THE TREE OF HANDS, and in 1987, writing as Barbara Vine, won her third Edgar from the Mystery Writers of America and the Crime Writers' Assocation Gold Dagger Award for A DARK ADAPTED-EYE. Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Publications Fiction Publication Details Notes NO MAN'S The woman vicar of St Peter's Church may not be popular, but it still comes NIGHTINGALE as a profound shock when she is found strangled in her vicarage. Inspector 2014 Wexford is retired, but when asked to assist he readily agrees. What Hutchinson Wexford does not know is that the killer is far closer than he, or any one else, thinks. THE GIRL NEXT When the bones of two severed hands are discovered in a box, an DOOR investigation into a long buried crime of passion begins. And a group of 2014 friends, who played together as children, begin to question their past. Hutchinson United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Publication Details Notes THE CHILD'S What sort of betrayal would drive a brother and sister apart? CHILD (as Barbara When Grace and her brother Andrew inherit their grandmother's house in Vine) Hampstead, they decide to move in together.