5163 19525 Retelling Tales 1 Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New Illtydian Spring 2020

h T A visit to Mansion House very year, His Grace Archbishop George Stack visits the Lord Mayor of Cardiff for a formal Evisit. For this year’s visit, he invited pupils from SPRING/GWANWYN 2020 SPRING/GWANWYN Cardiff’s Catholic secondary schools and Cardiff’s , fe wnawn wahaniae wnawn , fe T Catholic sixth form college to accompany him on this visit. Invited were St Illtyd’s, Corpus Christi and Mary Immaculate Catholic High Schools along with St ghris David’s Catholic Sixth Form College. Four Year 8 pupils n represented St Illtyd’s on this visit- Lauren Burns, Cohen Fender, Perseverance Mbango and Camille Miteleji. Together with His Grace, pupils met the Lord works with” and Camille added “I feel blessed to have Mayor of Cardiff- Councillor Daniel De’Ath and learnt gone on this visit.” Following the meeting with the Lord more about his role within the city of Cardiff. Pupils Mayor, pupils had a tour of Mansion House and saw were able to ask questions about issues related to the the wealth of treasures that have been gifted to the city and that they were interested in. Cohen said “The city of Cardiff. They even got to see the bedroom that Lord Mayor shared his knowledge of the charities he Nelson Mandela slept in when he visited. yda’n gilydd yng gilydd yda’n g head’s message | NEGES Y PENNAETH e • t appears that I am not alone be successful. This is C in feeling that this school year reflected in the other Iis flying along. -

Sixth Form Admissions Policy

2016/2017LLANISHEN HIGH SCHOOL Sixth Form Admissions SIXTHPolicy FORM ADMISSIONS POLICY Llanishen High School This document contains the specific policy and associated information related to gaining entry to the 16 to 19 learning environment at Llanishen High This document contains the specific policy and associated information related to gaining entry to the 16School. to 19 learning environment at Llanishen High School. Responsible Staff Member: Mrs E Lloyd (Leader of Learning 16-19) Approved by Governing Body: February 2013 To be reviewed: Spring term 2016 Responsible Staff Member: Mrs E Lloyd, (Leader of Learning 16-19) Approved by Governing Body: February 2013 To be reviewed: Spring 2016 Llanishen High School Sixth Form Admissions Policy Introduction Llanishen High School prides itself on having a thriving and successful sixth form taking around 300 students through their 16-19 learning experience. We enhance every student’s further education experience thus providing them with a greater opportunity to progress to higher education or personal career choices. Llanishen High School welcomes interest from our existing Year 11 pupils and any other interested pupils outside our own community. The Sixth Form Prospectus details the subjects on offer and entry qualifications for each. The Sixth Form will use the WJEC examination board predominantly from September 2016 to deliver 31 Level 3 subjects. We offer BTEC Sport Level 3 (Development, Coaching & Fitness), BTEC Performing Arts and BTEC Health & Social Care which is at the moment under Pearson/Edexcel examination board. All Llanishen High School Sixth Form students undertake the Advanced Welsh Baccalaureate. To further widen curriculum choice we operate a timetable that is closely linked, with our cluster schools comprising of Whitchurch High, Cardiff High, Cathays High and Cardiff and Vale College. -

Sally Davis 24Th September, 2010 Dates for Your Diary Further Ahead

th th 12 – 18 October, 2012 www.howellsth -cardiff.gdst.net www.howells-cardiff.gdst.net 24 September, 2010 This week we have had a major house event to raise money for Headway. Headway is a national charity with a base in Cardiff which aims to improve life after brain injury and provide information, support and services to people affected by brain injury, their family and carers. Every day this week, different year groups within the College and Senior School have brought in cakes or cookies as part of the Great Howell’s Bake-Off. Every entry has received two house points and Mrs Price and the kitchen staff have been delighted to be the judges of what may well become an annual competition. House points have been awarded for the best tasting, the best presentation and the most creative cakes, and I am delighted to tell you the results are: Baldwin wins with 394 points, Trotter with 287 points, Kendall with 240 points and Lewis with 200 points. The amount of money raised for Headway is nearly £500. Well done to everyone who has made, judged, bought and eaten cakes this week! Dates for Your Diary On Wednesday, I attended the Extended Project presentations by Year 13. I was extremely impressed by the standard of the presentations given by College students. The eight students taking part spoke to the audience confidently and knowledgably on the topics they had chosen to study. I heard about Statistics and Football, Face Further Ahead Transplants and Stradivarius violins, to mention just a few of the many and varied topics that were covered. -

My Ref: NJM/LS Your Ref

Your Ref: FOI 02146 Dear Mr McEvoy, Thank you for your request under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 about school governors, received on 13/07/12. Your Request asked for: Can you list governors in all primary and secondary schools in the LEA? Can you list all county and community councillors and the governing bodies on which they serve? Can you list the Chair of governors for all primary and secondary schools in the LEA? Can you give the total spend on supply teaching agency staff in the LEA, specifying schools and specifying how much goes to each agency from each school? We have considered your request and enclose the following information: Attached excel files containing information requested. With regards to the information supplied on agency spend, we cannot break the figures down by agency as Cardiff Council has no recorded information relating to chequebook schools and the agencies they may use, as they hold their own financial information. You can contact them directly for further details. If you have any queries or concerns, are in any way dissatisfied with the handling of your request please do not hesitate to contact us. If you believe that the information supplied does not answer your enquiry or if you feel we have not fully understood your request, you have the right to ask for an independent review of our response. If you wish to ask for an Internal Review please set out in writing your reasons and send to the Operational Manager, Improvement & Information, whose address is available at the bottom of this letter. -

Admission Criteria

Appendix 1 Cardiff Council: Admission Criteria October 2017 Professor Chris Taylor [email protected] Wales Institute of Social & Economic Research, Data & Methods (WISERD) 029 20876938 Cardiff University, School of Social Sciences @profchristaylor Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Context for admissions in Cardiff .......................................................................................................................... 2 3. Cardiff school admissions ......................................................................................................................................... 4 4. Analysis of Cardiff school admissions .................................................................................................................... 6 5. Review of other local authority admission arrangements .............................................................................. 16 6. School admissions research ................................................................................................................................... 21 6.1 Admission authorities............................................................................................................................................. 21 6.2 School preferences ................................................................................................................................................ -

Council Minutes 21/07/11 (197K)

73 THE COUNTY COUNCIL OF THE CITY & COUNTY OF CARDIFF The County Council of the City & County of Cardiff met at City Hall, Cardiff on Thursday 21 July, 2011 to transact the business set out in the Council Summons dated 15 July 2011. Present: County Councillor Delme Bowen, Lord Mayor (in the Chair); County Councillor Jayne Cowan, Deputy Lord Mayor. County Councillors Ali, Aubrey, Aylwin, Berman, Bowden, Bridges, Burfoot, Burns, Carter, Chaundy, Clark, Ralph Cook, Richard Cook, Cox, Kirsty Davies, Foley, Ford, Furlong, Gasson, Goddard, Goodway, Gordon, Grant, Greening, Griffiths, Clarissa Holland, Martin Holland, Hooper, Howells, Hudson, Hyde, Ireland, Islam, Jerrett, Brian Jones, Margaret Jones, Jones-Pritchard, Joyce, Kelloway, Macdonald, McEvoy, McKerlich, Montemaggi, David Morgan, Derrick Morgan, Elgan Morgan, Page, Jacqueline Parry, Patel, Pearcy, Pickard, Piper, David Rees, Dianne Rees, Robson, Rogers, Salway, Singh, Stephens, Wakefield, Walker, Walsh, Williams and Woodman. Apologies: County Councillors Finn, Lloyd, Linda Morgan, Keith Parry, Rowland-James and Smith (Prayers were offered by Professor John Morgan) 39 : MINUTES The minutes of the meeting held on 16 June 2011 were approved as a correct record and signed by the Chairman. 40 : DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST The Chairman reminded Members of their responsibility under Article 16 of the Members’ Code of Conduct to declare any interest, & to complete Personal Interest forms, at the commencement of the item of business. (Councillor Kirsty Davies declared a personal interest in Items 4 and 16 matters relating to the Cardiff & Vale Music Service as her mother works for the Music Service. Councillor Pearcy declared a personal interest in Item 6 Estyn Inspection Report as her husband works in a Welsh Medium Secondary School in Cardiff) County Council of the City & County of Cardiff 21 July 2011 74 41 : LORD MAYOR’S ANNOUNCEMENTS (a) Microphone System, Webcasting and recording of proceedings Members were reminded of a decision of the Constitution Committee on 10 July, 2008 to webcast the Council meeting. -

Appendix 6 Impact Analysis: Current Patterns of Demand Across the City in the Context of Feeder School Admission Criterion Option (Option B)

Appendix 6 Impact Analysis: current patterns of demand across the city in the context of feeder school admission criterion option (Option B) Analysis of the most recent verified PLASC (Pupil Level Annual School Census) data was carried out to give an indication of the alignment between existing patterns of school place provision and demand, if a feeder school criterion was implemented (Option B). For the purposes of data analysis, the focus was placed on the Year 4 cohort as it represented the year group transitioning to secondary school in which the admission arrangements for 2019/20 would apply. A comparison exercise was undertaken between the PAN of secondary schools against the numbers of pupils who are resident within catchment and are also attending the community primary schools nested within the secondary school catchment. It was found that 4 of the 13 schools had more pupils resident within catchment and attending feeder schools than could be accommodated in their linked secondary schools: Cardiff West Community High School (270 pupils in catchment, 240 PAN) Eastern High (343 pupils, 240 PAN) Fitzalan High School (386 pupils, 300 PAN) Llanishen High School (394 pupils, 300 PAN) Further to this approach, comparison of the aggregate Published Admission Number (PAN) of the feeder schools to their respective linked secondary schools, indicated that only 6 of the 13 secondary schools would potentially be able to accommodate all pupils from their respective feeder primary schools, as the aggregate PAN in primary schools is less than -

Colleague, Critic, and Sometime Counselor to Thomas Becket

JOHN OF SALISBURY: COLLEAGUE, CRITIC, AND SOMETIME COUNSELOR TO THOMAS BECKET By L. Susan Carter A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History–Doctor of Philosophy 2021 ABSTRACT JOHN OF SALISBURY: COLLEAGUE, CRITIC, AND SOMETIME COUNSELOR TO THOMAS BECKET By L. Susan Carter John of Salisbury was one of the best educated men in the mid-twelfth century. The beneficiary of twelve years of study in Paris under the tutelage of Peter Abelard and other scholars, John flourished alongside Thomas Becket in the Canterbury curia of Archbishop Theobald. There, his skills as a writer were of great value. Having lived through the Anarchy of King Stephen, he was a fierce advocate for the liberty of the English Church. Not surprisingly, John became caught up in the controversy between King Henry II and Thomas Becket, Henry’s former chancellor and successor to Theobald as archbishop of Canterbury. Prior to their shared time in exile, from 1164-1170, John had written three treatises with concern for royal court follies, royal pressures on the Church, and the danger of tyrants at the core of the Entheticus de dogmate philosophorum , the Metalogicon , and the Policraticus. John dedicated these works to Becket. The question emerges: how effective was John through dedicated treatises and his letters to Becket in guiding Becket’s attitudes and behavior regarding Church liberty? By means of contemporary communication theory an examination of John’s writings and letters directed to Becket creates a new vista on the relationship between John and Becket—and the impact of John on this martyred archbishop. -

Background: What Was the Church and Why Was It Important?

Background: What was the Church and why was it important? To fully understand the issues at stake in this topic, we need firstly to work out what the Church was and why it was so important during this time period. What is the Church? When I use the word ‘Church’ it generally means everybody working for the Church, from the Pope at its head, down to Archbishop, Bishops, the priests and clerks. It also includes all of the buildings and land attached to Christianity and the money that comes in from those lands. When we refer to ‘The Church’ it means the whole institution, not just a physical building, i.e. the village church. Why was the Church so important? In medieval England, the Church dominated everybody's life. All Medieval people - be they village peasants, barons, knights, kings or towns people - believed that God, Heaven and Hell existed The control the Church had over the people was total. For example, peasants worked for free on church land for a certain number of days a year and had to give 10% of their earnings to the Church (this payment was called a Tithe) The Church was very wealthy and owned lots of land, some reasons are: - If you died you had to pay to be buried on Church lands - If you were born you had to give a donation in order to be baptised - You could buy ‘Indulgences’ to guarantee you would go to heaven. Interestingly, when Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries (buildings where monks lived) in the 1500’s he received 25% of total land in England. -

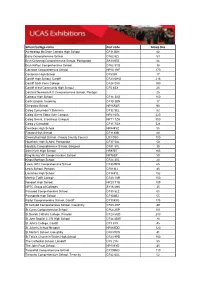

School/College Name Post Code Group Size

School/college name Post code Group Size Archbishop McGrath Catholic High School CF312DN 82 Barry Comprehensive School CF62 8ZJ 53 Bryn Celynnog Comprehensive School, Pontypridd SA131ES 84 Bryn Hafren Comprehensive School CF62 9YQ 38 Caerleon Comprehensive School NP18 1NF 170 Cantonian High School CF53JR 17 Cardiff High School, Cardiff CF23 6WG 216 Cardiff Sixth Form College CF24 0AA 190 Cardiff West Community High School CF5 4SX 25 Cardinal Newman R C Comprehensive School, Pontypri 25 Cathays High School CF14 3XG 160 Celtic English Academy CF10 3BN 17 Chepstow School NP16RLR 90 Coleg Cymunedol Y Dderwen CF32 9EL 82 Coleg Gwent Ebbw Vale Campus NP23 6GL 220 Coleg Gwent, Crosskeys Campus NP11 7ZA 500 Coleg y Cymoedd CF15 7QX 524 Cwmbran High School NP444YZ 55 Fitzalan High School CF118XB 80 Gwernyfed High School - Powys County Council LD3 0SG 100 Hawthorn High School, Pontypridd CF37 5AL 50 Heolddu Comprehensive School, Bargoed CF81 8XL 30 John Kyrle High School HR97ET 165 King Henry VIII Comprehensive School NP76EP 50 Kings Monkton School CF24 3XL 20 Lewis Girls' Comprehensive School CF381RW 65 Lewis School, Pengam CF818LJ 45 Llanishen High School CF145YL 152 Merthyr Tydfil College CF48 1AR 150 Newport High School NP20 7YB 109 NPTC Group of Colleges SY16 4HU 35 Pencoed Comprehensive School CF35 5LZ 65 Pontypridd High School CF104BJ 55 Radyr Comprehensive School, Cardiff CF158XG 175 St Cenydd Comprehensive School, Caerphilly CF83 2RP 49 St Cyres Comprehensive School CF64 2XP 101 St Davids Catholic College, Penylan CF23 5QD 200 St John Baptist -

Our January Parishscapes Newsletter

Doccombe Parishscapes Newsletter January 2017 Welcome to our January Parishscapes Newsletter We wish everyone a wonderful new year ahead and our Parishscapes project is set to accelerate in 2017 with a lot planned. In this newsletter we thought we would give you some background history to the story of Thomas Becket so hope you find this interesting and informative. In the meantime our main work has been to continue transcribing and translating the manorial records of Doccombe manor. One group has been working their way through the manorial courts of the reign of Henry VIIth where some interesting references to Charcoal pits in the woods and tin-mining have emerged. The other group have looked at a number of C17th leases of tenancies, but also of the whole manor and the woods. They are following this with some interesting biographical work on the men who leased the manor. We also have some stimulating talks and events coming up. We'll keep you posted as we schedule them - look out for a fascinating evening with Professor Nicholas Vincent below. For more up-to-date information and our blog go to http://www.doccombeparishscapes.co.uk/ Project Lead Bill Hardiman / Project Manager-Administration Katheryn Hope The Story of Thomas Becket Thomas Becket’s death remains one of the most famous stories associated with Medieval England. Becket was a 12th century chancellor and archbishop of Canterbury whose murder resulted in his canonisation. Thomas Becket was born in 1118, the son of a prosperous London merchant. He was well educated first at Merton priory, then in a City of London school, and finally in Paris. -

Celebrating 30 Years of Inspiring Future Engineers

WELSH ENGINEERING TALENT FOR THE FUTURE EESW WELSH ENGINEERING TALENT FOR THE FUTURE EESW STEM STEM Welsh Engineering Talent for the Future Cymru Issue Welsh Engineering Talent for the FutureSeptember Cymru talent No. 23 talent2019 Issue No. 18 THE JOURNAL OF THE ENGINEERING EDUCATION SCHEME WALES September 2014 TALENIssue No. 18 THE JOURNAL OF THE ENGINEERING EDUCATTION SCHEME WALES September 2014 INSIDE ADDRESSING SHORTFALL: 3 Cardiff University plays its part WINNER: Ysgol Plasmawr's Daniel 4 Clarke – Student of the Year ProspectiVE ENgiNeeriNG stUDENts at EESW'S HeaDStart CYMRU EVENT at SwaNsea UNIVersitY F1 IN SCHOOLS: Celebrating 30 years of Another excellent year 8 for teams in Wales inspiring future engineers ow in our 30th year, the ROBERT CATER targets and our ESF funding has NEngineering Education CEO, Engineering Education Scheme been extended and is currently Scheme Wales (EESW) currently Wales secure until 2021. engages with more than 8,000 Funding from the government students per year across both continues to ensure we can primary and secondary sectors. The foundation for the development of continue to operate across the scheme has grown significantly EESW was established. whole of Wales. JagUAR challenge: since it was first established Over the years the The ESF funding allowed Engaging young minds 12 by Austin Matthews in scheme grew and us to offer a broader range of in a fun and exciting way 1989 (see page 2) with developed to experiences to a wider 11-19 age funding from the involve larger range. Royal Academy of numbers and We continued with the sixth- Engineering. worked with form industry-linked project and Mr Matthews and an increasing added a range of activities for Key two other helpers 3oyears number of Stage 3 under the umbrella of established EESW as companies.