SFRA Newsletter 37

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lost World: England 1933-1936 PDF Book

LOST WORLD: ENGLAND 1933-1936 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dorothy Hartley,Lucy Worsley,Adrian Bailey | 272 pages | 31 Oct 2012 | PROSPECT BOOKS | 9781903018972 | English | Blackawton, United Kingdom Lost World: England 1933-1936 PDF Book Brian Stableford makes a related point about Lost Worlds: "The motif has gradually fallen into disuse by virtue of increasing geographical knowledge; these days lost lands have to be very well hidden indeed or displaced beyond some kind of magical or dimensional boundary. Smoo Cave 7. Mat Johnson 's Pym describes giant white hominids living in ice caves. Contemporary American novelist Michael Crichton invokes this tradition in his novel Congo , which involves a quest for King Solomon's mines, fabled to be in a lost African city called Zinj. Much of the material first appeared in her weekly columns for the Daily Sketch from to and 65 of these, together with some of the author's evocative photos, have been collected in this book. Most popular. Rhubarbaria : Recipes for Rhubarb. EAN: Caspak in the Southern Ocean. Topics Paperbacks. Cancel Delete comment. Crusoe Warburton , by Victor Wallace Germains , describes an island in the far South Atlantic, with a lost, pre-gunpowder empire. New England Paperback Books. Here the protagonists encounter an unknown Inca kingdom in the Andes. New other. Updating cart She describes meeting an old woman in sand dunes by the sea, cutting marram grass, "gray as dreams and strong as a promise given". Create a commenting name to join the debate Submit. She was also a teacher herself and wrote much journalism, principally on country matters. -

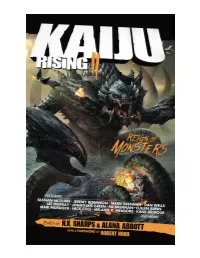

Kaiju-Rising-II-Reign-Of-Monsters Preview.Pdf

KAIJU RISING II: Reign of Monsters Outland Entertainment | www.outlandentertainment.com Founder/Creative Director: Jeremy D. Mohler Editor-in-Chief: Alana Joli Abbott Publisher: Melanie R. Meadors Senior Editor: Gwendolyn Nix “Te Ghost in the Machine” © 2018 Jonathan Green “Winter Moon and the Sun Bringer” © 2018 Kane Gilmour “Rancho Nido” © 2018 Guadalupe Garcia McCall “Te Dive” © 2018 Mari Murdock “What Everyone Knows” © 2018 Seanan McGuire “Te Kaiju Counters” © 2018 ML Brennan “Formula 287-f” © 2018 Dan Wells “Titans and Heroes” © 2018 Nick Cole “Te Hunt, Concluded” © 2018 Cullen Bunn “Te Devil in the Details” © 2018 Sabrina Vourvoulias “Morituri” © 2018 Melanie R. Meadors “Maui’s Hook” © 2018 Lee Murray “Soledad” © 2018 Steve Diamond “When a Kaiju Falls in Love” © 2018 Zin E. Rocklyn “ROGUE 57: Home Sweet Home” © 2018 Jeremy Robinson “Te Genius Prize” © 2018 Marie Brennan Te characters and events portrayed in this book are fctitious or fctitious recreations of actual historical persons. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the authors unless otherwise specifed. Tis book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. Published by Outland Entertainment 5601 NW 25th Street Topeka KS, 66618 Paperback: 978-1-947659-30-8 EPUB: 978-1-947659-31-5 MOBI: 978-1-947659-32-2 PDF-Merchant: 978-1-947659-33-9 Worldwide Rights Created in the United States of America Editor: N.X. Sharps & Alana Abbott Cover Illustration: Tan Ho Sim Interior Illustrations: Frankie B. -

Small Renaissances Engendered in JRR Tolkien's Legendarium

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2017 'A Merrier World:' Small Renaissances Engendered in J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium Dominic DiCarlo Meo Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Meo, Dominic DiCarlo, "'A Merrier World:' Small Renaissances Engendered in J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium" (2017). Senior Honors Theses. 555. http://commons.emich.edu/honors/555 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. 'A Merrier World:' Small Renaissances Engendered in J. R. R. Tolkien's Legendarium Abstract After surviving the trenches of World War I when many of his friends did not, Tolkien continued as the rest of the world did: moving, growing, and developing, putting the darkness of war behind. He had children, taught at the collegiate level, wrote, researched. Then another Great War knocked on the global door. His sons marched off, and Britain was again consumed. The "War to End All Wars" was repeating itself and nothing was for certain. In such extended dark times, J. R. R. Tolkien drew on what he knew-language, philology, myth, and human rights-peering back in history to the mythologies and legends of old while igniting small movements in modern thought. Arthurian, Beowulfian, African, and Egyptian myths all formed a bedrock for his Legendarium, and fantasy-fiction as we now know it was rejuvenated.Just like the artists, authors, and thinkers from the Late Medieval period, Tolkien summoned old thoughts to craft new creations that would cement themselves in history forever. -

The World of Fantasy Literature Has Little to Do with the Exotic Worlds It Describes

The world of fantasy literature has little to do with the exotic worlds it describes. It is generally tied to often well-earned connotations of cheap writing, childish escapism, overused tropes copied and pasted straight out of The Lord of the Rings, and a strong commercial vitality. Perhaps it is the comforting predictability that draws me in—but the same could be said of the delight that I feel when some clever author has taken the old and worn hero-cycle and turned it inside out. Maybe I just like dragons and swords. It could be that the neatly packaged, solvable problems within a work of fantasy literature, problems that are nothing like the ones I have to deal with, such as marauding demons or kidnappings by evil witches, are more attractive than my own more confusing ones. Somehow they remain inspiring and terrifying despite that. Since I was a child, fantasy has always been able to captivate me. I never spared much time for the bland narratives of a boy and his dog or the badly thought-out antics of neighborhood friends. I preferred the more dangerous realms of Redwall, populated by talking animals, or Artemis Fowl, a fairy-abducting, preteen, criminal mastermind. In fact, reading was so strongly ingrained in me that teachers, parents and friends had to, and on occasion still need to, ask me to put down my book. I really like reading, and at some point that love spilled over and I started to like writing, too. Telling a story does not have to be deep or meaningful in its lessons. -

Discussion About Edwardian/Pulp Era Science Fiction

Science Fiction Book Club Interview with Jess Nevins July 2019 Jess Nevins is the author of “the Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana” and other works on Victoriana and pulp fiction. He has also written original fiction. He is employed as a reference librarian at Lone Star College-Tomball. Nevins has annotated several comics, including Alan Moore’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Elseworlds, Kingdom Come and JLA: The Nail. Gary Denton: In America, we had Hugo Gernsback who founded science fiction magazines, who were the equivalents in other countries? The sort of science fiction magazine that Gernsback established, in which the stories were all science fiction and in which no other genres appeared, and which were by different authors, were slow to appear in other countries and really only began in earnest after World War Two ended. (In Great Britain there was briefly Scoops, which only 20 issues published in 1934, and Tales of Wonder, which ran from 1937 to 1942). What you had instead were newspapers, dime novels, pulp magazines, and mainstream magazines which regularly published science fiction mixed in alongside other genres. The idea of a magazine featuring stories by different authors but all of one genre didn’t really begin in Europe until after World War One, and science fiction magazines in those countries lagged far behind mysteries, romances, and Westerns, so that it wasn’t until the late 1940s that purely science fiction magazines began appearing in Europe and Great Britain in earnest. Gary Denton: Although he was mainly known for Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle also created the Professor Challenger stories like The Lost World. -

Fantasy Literature: Definition”

Written version of the lecture Malin Alkestrand: “Fantasy literature: Definition” What is fantasy literature? This is a question that has been debated and answered in numerous studies on fantasy literature, but a quick overview of the studies shows that there is not one simple answer to this question. Different scholars mention different criteria for the genre, and they include different literary works in their descriptions of the genre. However, there are a few basic aspects that they all define as central for fantasy literature. In the following, I will discuss a few different definitions of fantasy literature that clarify the most central characteristics of the genre. To begin with, I want to point out that there is a difference between fantastic literature and fantasy literature. Fantastic literature includes all kinds of literature that do not rely on a mimetic description of a world that is similar to reality, such as fantasy literature, science fiction, and horror (Irwin 1976:55). Fantasy literature, on the other hand, is one of the genres included within the wider concept of fantastic literature, but it displays genre characteristics which makes it very different from science fiction, for example. Whereas science fiction literature describes a possible future with advanced technology that does not yet exist, but could potentially exist in 10, 100 or 1000 years, fantasy literature portrays worlds where the supernatural exists (see James & Mendlesohn 2012:3). Magic, magical creatures, spells, and dragons introduce a world that does not follow the natural laws that govern our own reality. According to William Robert Irwin (1976:155) fantasy literature can be understood as the result of presenting the supernatural as real and always present. -

Mythopoeia, Colonialism and Redress in the Morobe Goldfields in Papua New Guinea

GOLD, TADPOLES AND JESUS IN THE MANGER: MYTHOPOEIA, COLONIALISM AND REDRESS IN THE MOROBE GOLDFIELDS IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA DANIELE MORETTI In 1936 Beatrice Blackwood became the first ethnographer to work with the Anga people of Papua New Guinea (PNG).1 In her own words, her aim was to learn “what [she] could of the life of a modern Stone Age people..., for in this way an ethnologist can sometimes fill up some of the gaps in the archaeological record” (Blackwood 1939: 11). Of course, this attempt at anthropological time travel (Fabian 1983) was only made possible by the “pacification” of a small number of Upper Watut villages following the discovery of gold in the neighbouring Wau-Bulolo Valley and Mount Kaindi over the previous decade. For the Anga of the Bulolo District, the opening of the Morobe Goldfields in the 1920s marked the beginning of a new colonial epoch. Beyond that, the event encouraged prospectors and administration to push inland in search of similar strikes, thus promoting the spread of colonial power, not just to the core of Anga country but also to the wider Highlands region. Between the 1920s and PNG national independence in 1975 the Morobe Goldfields produced great mineral riches that transformed the townships of Wau and Bulolo into booming industrial enclaves and sustained colonial expansion throughout the Mandated Territory of New Guinea (a political unit subsequently united with Papua under colonial rule). Yet little of this wealth was spent for the benefit of the Upper Watut or of the Anga more generally. What is more, just as independence approached and growing numbers of Anga became involved in the Goldfields’ economy, the Bulolo District’s large-scale mining industry ground to a halt and local employment opportunities and services declined significantly. -

The Lost World Points for Understanding Answer

ELEMENTARY LEVEL ■ The Lost World by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Points for Understanding 1 6 1 He was a reporter for a newspaper in London. The news- 1 Gomez and Miguel had pushed the tree into the abyss. paper is called the ‘Daily Gazette’. 2 Professor Challenger They had done it because Gomez hated Roxton. Roxton had said that he had found some wonderful animals in South killed Pedro Lopez. He was Gomez’ brother. 2 They asked America. Many people didn’t believe him. Malone went to see him to stay in the camp at the bottom of the rock. They Professor Challenger. He wanted to find out if Challenger was asked him to send one of the Indians to get some long ropes. telling the truth. 3 He had a very large head with a red face And they asked him to tell the Indian to send Malone’s report and grey eyes. He had a long black beard. His hands were big, to Mr McArdle in London. 3 A huge animal. Professor strong and covered with thick black hair. 4 Malone asked Challenger said that he thought a dinosaur had made them. Challenger some questions. But they were not very good 4 He was looking into a pit where hundreds of pterodactyls questions. Challenger soon knew that Malone was not a sci- were sitting. 5 Something had broken things in the camp. It ence student. Challenger guessed that he was a reporter. He had taken the food from some of their tins. tried to throw him out of the house. -

KING KONG IS BACK! E D I T E D B Y David Brin with Leah Wilson

Other Titles in the Smart Pop Series Taking the Red Pill Science, Philosophy and Religion in The Matrix Seven Seasons of Buffy Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Discuss Their Favorite Television Show Five Seasons of Angel Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Discuss Their Favorite Vampire What Would Sipowicz Do? Race, Rights and Redemption in NYPD Blue Stepping through the Stargate Science, Archaeology and the Military in Stargate SG-1 The Anthology at the End of the Universe Leading Science Fiction Authors on Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Finding Serenity Anti-heroes, Lost Shepherds and Space Hookers in Joss Whedon’s Firefly The War of the Worlds Fresh Perspectives on the H. G. Wells Classic Alias Assumed Sex, Lies and SD-6 Navigating the Golden Compass Religion, Science and Dæmonology in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials Farscape Forever! Sex, Drugs and Killer Muppets Flirting with Pride and Prejudice Fresh Perspectives on the Original Chick-Lit Masterpiece Revisiting Narnia Fantasy, Myth and Religion in C. S. Lewis’ Chronicles Totally Charmed Demons, Whitelighters and the Power of Three An Unauthorized Look at One Humongous Ape KING KONG IS BACK! E D I T E D B Y David Brin WITH Leah Wilson BENBELLA BOOKS • Dallas, Texas This publication has not been prepared, approved or licensed by any entity that created or produced the well-known movie King Kong. “Over the River and a World Away” © 2005 “King Kong Behind the Scenes” © 2005 by Nick Mamatas by David Gerrold “The Big Ape on the Small Screen” © 2005 “Of Gorillas and Gods” © 2005 by Paul Levinson by Charlie W. -

This Character Is Portrayed As Unfeminine and “Married” to Their Work. They Can Be Transformed by a Love Interest, but Reinf

Andra Campbell This is Dr. Flicker! We’re going to use her paper “Between Hey everyone! My names Andra and I want Brains and Breasts-Women Scientists in Fiction Film: On the to tell you about the Marginalization and Sexualization of Scientific Competence” to ways that women in look at ways women in STEM in media have been portrayed by looking at the common-stereotypes throughout films . STEM have been represented in media! Hi everyone, I’m Dr. Flicker! Stereotype 1… This character is portrayed as unfeminine and “married” to their work. They can be transformed by a love interest, but reinforce the stereotype that feminine women can’t be intelligent. Check out Dr. Peterson from the movie Spellbound (1945), or Amy Fowler from the Big Bang Theory (2007) for an example! Stereotype 2… This portrays a woman who must be “one of the guys” in order to prove herself. She is sometimes inferior to her male counterparts. An example is Dr. Leavitt from The Andromeda Strain (1971) or Dr. Augustine from Avatar (2009). This portrayal reinforces the negative stereotype that science is for “The Andromeda Strain (1971).” IMDb, www.imdb.com/ men. Stereotype 3… Dr. Sarah Harding from The Lost World: Jurassic Park This character has little (1997) is an example of significance towards The Naive Expert you may the scientific theme of recognize! the movie, is feminine, and often a love interest. Her naïveté often gets her in trouble, with a man “The Lost World: Jurassic Park (Universal, 1997).” Heritage rescuing her. Auctions, 2 Sept. 2018, movieposters.ha.com/itm/ movie-posters/science-fiction/the-lost-world- jurassic-park-universal-1997-lenticular-one- sheet-27-x-41-science-fiction/a/161835-51233.s. -

Progress in the Discourse of Todorovian, Tolkienian and Mystic Fantasy Theory Greg Bechtel University of New Brunswick

“There and Back Again”: Progress in the Discourse of Todorovian, Tolkienian and Mystic Fantasy Theory Greg Bechtel University of New Brunswick is always an act of creative fantasy. T e critic constructs an internally consistent structure from fragments of texts, observations and (inevitably) personal biases, and this construc- tion begins with a what-if proposition.proposition. WWhathat iiff lliteraryiterary ttextsexts hhaveave ppoliticalolitical implications? Might there be a correlation between a writer’s gender and the language available for that writer’s expression? Could it be that lan- guage itself is indeterminate, and, if so, what impact would this have on the Western tradition of liberal humanism? e critic speculates, fabricates an imagined network of logical implications and, in the case of publication, presents this fabrication for serious consideration by a scholarly commu- nity. e following act of literary criticism is, like all such acts, a fantasy of critical discourse. To survey a history of fantasy criticism—as I shall in this paper—is to build a meta-fantasy, a fantasy of fantasies of fantasy. at fantasy has been dismissed or excluded from the canon of West- ern literature is a commonplace of the critical work on the genre. is sense of exclusion may be the strongest recurring theme across all forms of fantasy criticism, an otherwise highly heterogeneous fi eld. Karen Michalson, for example, introduces her exploration of Victorian fantasy by suggesting that “certain readers will object to my subject matter as well ESC .. (December(December ):): -- as to my approach. Fantasy literature does not enjoy the kind of critical attention or prestige that other literary genres, like the realistic novel do” G B is (i). -

Golden Fantasy: an Examination of Generic & Literary Fantasy in Popular Writing Zechariah James Morrison Seattle Pacific Nu Iversity

Seattle aP cific nivU ersity Digital Commons @ SPU Honors Projects University Scholars Spring June 3rd, 2016 Golden Fantasy: An Examination of Generic & Literary Fantasy in Popular Writing Zechariah James Morrison Seattle Pacific nU iversity Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Morrison, Zechariah James, "Golden Fantasy: An Examination of Generic & Literary Fantasy in Popular Writing" (2016). Honors Projects. 50. https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects/50 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the University Scholars at Digital Commons @ SPU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ SPU. Golden Fantasy By Zechariah James Morrison Faculty Advisor, Owen Ewald Second Reader, Doug Thorpe A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University Scholars Program Seattle Pacific University 2016 2 Walk into any bookstore and you can easily find a section with the title “Fantasy” hoisted above it, and you would probably find the greater half of the books there to be full of vast rural landscapes, hackneyed elves, made-up Latinate or Greek words, and a small-town hero, (usually male) destined to stop a physically absent overlord associated with darkness, nihilism, or/and industrialization. With this predictability in mind, critics have condemned fantasy as escapist, childish, fake, and dependent upon familiar tropes. Many a great fantasy author, such as the giants Ursula K. Le Guin, J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis and others, has recognized this, and either agreed or disagreed as the particulars are debated.