Firearms and the Shooting Sports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Rifle Association the Nra Handbook

NATIONAL RIFLE ASSOCIATION THE NRA HANDBOOK Including the NRA RULES OF SHOOTING and the Programme of THE IMPERIAL MEETING FRIDAY 12 JUNE TO SATURDAY 25 JULY 2020 This Handbook is issued by, and the Rules, Regulations and Conditions are made by, order of the Council and approved on 22 February 2020. This document is effective from 30 March 2020. Published by the National Rifle Association, Bisley Camp, Brookwood, Woking, Surrey, GU24 0PB Tel: 01483 797777 Fax: 01483 797285 £9.50 10 11 THE HANDBOOK OF THE NATIONAL RIFLE ASSOCIATION This book contains three Volumes, each containing Parts, Sections and Paragraphs. Appendices appear at the end of each Volume. Parts, Sections, Paragraphs and Appendices are all numbered consecutively through the entire book. To avoid repeating pronouns, the masculine form only is used throughout. Thus ‘he’ should be read as ‘he/she’, ‘him’ as ‘him/her’, and ‘his’ as ‘his/her(s)’. The 24 hour clock is used throughout. Volumes 4 to 6, the NRA Gallery Rifle and Pistol Handbook, the NRA Target Shotgun Handbook and the NRA Civilian Service Rifle and Practical Rifle Handbook, are published separately, but derive authority from the Council’s authorisation of this Handbook. Volume 7, the Classic and Historic Arms Handbook, is in preparation. This book is available in large print on A4 paper by application to Shooting Division. All Volumes of the Handbook are available as pdf downloads on the NRA website. Information contained in this Handbook is valid as at 22 February 2020. Changes will be notified via the NRA website, the NRA Journal and, if necessary, by e-mail and/or post. -

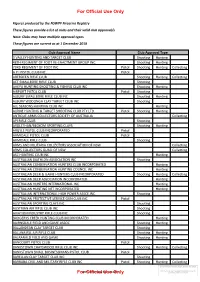

5842:ED Use - PAGE Only 1 Command, NSW Police Force

For Official Use Only Figures produced by the NSWPF Firearms Registry These figures provide a list of clubs and their valid club approval/s Note: Clubs may have multiple approval types These figures are current as at 1 December 2018 Club Approval Name Club Approval Type 3 VALLEY HUNTING AND TARGET CLUB Shooting Hunting 48TH REGIMENT OF FOOT RE-ENACTMENT GROUP INC. Shooting Hunting 73RD REGIMENT OF FOOT INC Pistol Shooting Hunting Collecting A P I PISTOL CLUB INC. Pistol ABERDEEN RIFLE CLUB Shooting Hunting Collecting ACT SMALLBORE RIFLE CLUB Shooting AHEPA HUNTING SHOOTING & FISHING CLUB INC Shooting Hunting AIRPORT PISTOL CLUB Pistol Shooting ALBURY SMALLBORE RIFLE CLUB INC Shooting Hunting ALBURY WODONGA CLAY TARGET CLUB INC Shooting ALL SEASONS HUNTING CLUB INC Hunting ALPINE HUNTING & TARGET SHOOTING CLUB PTY LTD Pistol Shooting Hunting ANTIQUE ARMS COLLECTORS SOCIETY OF AUSTRALIA Collecting API RIFLE CLUB Shooting ARDLETHAN/BECKOM SPORTING CLAYS Shooting Hunting ARGYLE PISTOL CLUB INCORPORATED Pistol ARMIDALE PISTOL CLUB Pistol ARMIDALE RIFLE CLUB Shooting ARMS AND MILITARIA COLLECTORS'ASSOCIATION OF NSW Collecting ARMS COLLECTORS GUILD OF NSW Collecting ASC HUNTING CLUB INC Hunting AUSTRALIAN BIATHLON ASSOCIATION INC Shooting AUSTRALIAN CONSERVATION HUNTERS CLUB INCORPORATED Hunting AUSTRALIAN CONSERVATION HUNTING COUNCIL INC Hunting AUSTRALIAN DEER & GAME HUNTERS CLUB INCORPORATED Shooting Hunting Collecting AUSTRALIAN DEER ASSOCIATION INCORPORATED Hunting AUSTRALIAN HUNTERS INTERNATIONAL INC Hunting AUSTRALIAN HUNTING NET INCORPORATED -

The Webley-Fosbery

From My Collection - The Webley-Fosbery When you have collected the whole Webley military revolver series, Mark I to mark VI, you might start to wonder ‘what next?’. The Webley British service revolver, developed in the 1880’s, was the most effective military sidearm of its day. However, by the turn of the century automatic pistols were making an appearance, with a number of different and competing technologies. The Borchardt/Luger toggle, Mauser/Bergman bolt and Browning slide actions are the best known. Amongst the other contenders was the quintessentially British Webley-Fosbery automatic revolver, the brainchild of Lieutenant Colonel George Fosbery, VC. Fosbery, ignoring all the other systems emerging in the 1890’s, devised a simple and ingenious method of harnessing the recoil energy of a fired round to rotate the cylinder and cock the hammer of a revolver. This was achieved by dividing the frame into two sections, with the upper part, consisting of barrel, cylinder and hammer assembly, fitted to slide to the rear of the lower part under the force of the recoil. A small vertical stud fixed to the lower section engages with zig-zag grooves on the outer surface of the cylinder, rotating it to bring the next chamber into line with the bore. At the same time the rearward movement of the upper section is used to cock the hammer. Apart from the fact that it cannot be fired ‘double action’, the operation of the Fosbery is otherwise similar to that of the top-break Webley service revolver. However, the cylinder is fixed and cannot be rotated with the action closed other than by firing a round or manually pushing the upper section rearward. -

Long Term Development

Long Term Development Target Shooting: a lifetime sport Copyright: Shooting Federation of Canada, 2021 Table of Contents 2 Acknowledgements 3 Foreword 4 Target Shooting is unique 4 Becoming involved in Target Shooting 5 The disciplines of Olympic Target Shooting 6 Target Shooting for athletes with a physical disability 8 Use of Firearms 8 Environmental Concerns 9 Why is LTD important for Target Shooting? 10 Current status of Target Shooting sports in Canada 11 The factors influencing LTD 15 The Stages of Long Term Development for Target Shooting 16 • Active Start 17 • FUNdamentals 18 • Learn to Shoot 19 • Train to Train 20 • Train to Compete 21 • Train to Win 22 • Active for Life: Target Shooting is a lifetime sport 24 Appendices 24 1. Glossary of Terms 26 2. Development of Mental Skills 30 3. Resource List 31 4. LTD Steering Committee LONG TERM DEVELOPMENT 1 Acknowledgements Shooting Federation of Canada (SFC) LTD Steering Committee: Bernie Harrison Istvan Balyi (LTD Expert Group) Mo Johnson Cathy Haines (Consultant) Rick Ward Susan Verdier (SFC Technical Director) The SFC acknowledges the contribution of the following individuals in the preparation of this document: Mike LaRochelle Keith Stieb Reg Potter Curtis Wennberg We also wish to thank the Federation of Canadian Archers, Biathlon Canada and the Canadian Fencing Federation for being role models with their Long Term Development framework documents, and for allowing us the use of some of their materials and ideas. 2 LONG TERM DEVELOPMENT Foreword The SFC has created this Long Term Development framework as a model for the development of athletes in the Target Shooting sports. -

Smallbore Rifle

January 2021 www.ssusa.org Coming Events NRA SANCTIONED TOURNAMENTS To be listed, NRA must sanction matches by the 15th of the month, two months prior to the month of the magazine issue. If you are interested in entering a tournament, contact the individual listed. For any cancellations or changes to this listing, please contact Shelly Kramer: [email protected], NRA Competitive Shooting Division. 1 January 2021 www.ssusa.org Legend A: NRA Approved Tournament OAR: Open Air Rifle R: NRA Registered Tournament OF: Offhand 1800: 1800-pt. match OP: Open 2700: 2700-pt. match ORF: Open Rimfire 3200: 3200-pt. match OS: Open Sights 6400: 6400-pt. match OUT: Outdoor 3P: 3-Position PAL: Palma 4P: 4-Position PC: Pistol Cartridge Lever Action Silh AIR: Air Pistol PI: Pistol AP: Action Pistol POS: Position BP: Black Powder POST: Postal BPS: Black Powder Scope PPC: Police Pistol Combat CFP: Center-Fire Pistol PRE: Precision CON: Conventional PRN: Prone CC: Creedmoor Cup PRO: Production DR: Distinguished Revolver PRF: Production Rimfire FC: F-Class RF: Rimfire FRP: Free Pistol RFP: Rapid-Fire Pistol FBP: Fullbore Prone SAR: Sporter Air Rifle HPR: High Power SBHP: Smallbore Hunter’s Pistol HPHR: High Power Hunting Rifle SBHR: Smallbore Hunting Rifle HPSR: High Power Sporting Rifle SBR: Smallbore Rifle HPSA: High Power Semi-Auto SC: Short Course HP: Hunter’s Pistol SO: Scope Only IN: Indoor SCLA: Smallbore Lever Action Silh Rifle IND: Individual SER: Service INSER: Interservice SP: Service Pistol INV: Invitational SPI: Sport Pistol ISO: Iron Sight Only SPT: Sporter JR: Junior SR: Service Rifle LA: Lever Action Silh Rifle STA: Standing LM: Leg Match STD: Standard LR: Long-Range STK: Stock Gun LTR: Light Rifle TAR: Target MET: Meters TM: Team MR: Mid-Range USTA: Unlimited Standing MRP: Mid-Range Prone WSP: Women’s Sport Pistol MS: Metallic Sights YD: Yards 2 January 2021 www.ssusa.org Table of Contents (Click the Left Mouse button to jump to a section) PISTOL ..................................................................... -

A 3D Tour Handgun History Dan Lovy

A 3D Tour Handgun History Dan Lovy I have a new toy, a 3D printer. I am amazed at the level of quality compared to its price. I'm printing out robots, cartoon characters and as many Star Trek ship models as I can find. The darn thing is running almost 24/7 and all my shelving is filling up with little plastic objects. First let me state that I am not a gun enthusiast. I own no fire arms and have been to a firing range once in my life. I believe that we have too many and they are too accessible, especially in the U.S. That having been said, I also have a fascination with the technological change that occurred during the industrial revolution. In some ways we are still advancing the technology that was developed in the late 19th and early 20th century. Fire arms, especially handguns, offer a unique window into all this. Advancement did not happen through increased complexity. A modern Glock is not much more complex than a Colt 1911. The number of parts in a pistol has been in the same range for nearly 200 years. Cars on the other hand gained complexity and added system after system. Advancement did not happen through orders of magnitude in performance. A 747 is vastly more capable than the Wright Flyer. One of the basic measures of a pistol is how fast can it shoot a bullet, that parameter has not really changed much, certainly not as much as the top speed of a car. -

Download Product Catalog

V6 HEADQUARTERS STAFFORD, TX SRT FABRICATION SUGAR LAND, TX ABOUT US Laser Shot provides affordable, alternative training solutions for military, ODZHQIRUFHPHQWSURIHVVLRQDOVDQGSURVKRRWHUV6LQFHLWVHVWDEOLVKPHQWLQ /DVHU6KRWKDVUHPDLQHGFRPPLWWHGWRGHYHORSLQJWKHPRVWUHDOLVWLF DQG SUDFWLFDO ¿UHDUP VLPXODWRUV FUHZ WUDLQLQJ VLPXODWRUV DQG OLYH¿UH Laser Shot, Inc. IDFLOLWLHVDYDLODEOHZRUOGZLGH &RUSRUDWH2I¿FH 4214 Bluebonnet Drive Stafford, Texas 77477 /DVHU 6KRW RIIHUV SURJUHVVLYH WUDLQLQJ VROXWLRQV WKDW DUH DSSOLFDEOH WR Phone: 281.240.1122 DOOVNLOOOHYHOVDGDSWDEOHIRULQGLYLGXDOFXVWRPHUQHHGV²DOOZKLOHIRFXVLQJ RQ ³WUDLQDV\RX¿JKW´ FRUH SULQFLSOHV 2XU WUDLQLQJ VROXWLRQV DXJPHQW H[LVWLQJ SURJUDPV ZLWK VDIH DOWHUQDWLYHV E\ XVLQJ WHFKQRORJLFDOO\ DGYDQFHG VLPXODWLRQV IRU LPPHUVLYH WUDLQLQJ ,Q OLYH¿UH IDFLOLWLHV WKH\ WXUQ FRQYHQWLRQDO PXQGDQH UDQJHV DQG VKRRW KRXVHV LQWR H[FHSWLRQDO FXWWLQJHGJHIDFLOLWLHV v10.5 SRT FABRICATION SUGAR LAND, TX CONTENTS SYSTEMS 06 TRAINING SOFTWARE 12 SIMULATED FIREARMS 29 ACCESSORIES 36 Shooting Range Technologies (SRT) )DEULFDWLRQ 730 Sartartia Rd RANGES 38 Sugar Land, Texas 77479 Phone: 281.240.1122 TECHNOLOGY 6LQFH/DVHU6KRWKDVUHVHDUFKHGFDPHUDWHFKQRORJ\WR¿QGDQRSWLPXPPHWKRGIRUWUDFNLQJVLPXODWHG¿UHDUPVXVLQJ YLVLEOHDQGLQIUDUHGODVHUV/DVHU6KRWFDPHUDVDUHWUXO\VWDWHRIWKHDUW:KHQFRPELQHGZLWK/DVHU6KRW¶VSURSULHWDU\VXESL[HO ODVHUWUDFNLQJDOJRULWKPWKHHQGUHVXOWLVWKHIDVWHVWDQGPRVWDFFXUDWHWUDFNLQJPHWKRGDYDLODEOHIRUVLPXODWHG¿UHDUPVRQWKH market today. /DVHU6KRW¶VFDPHUDWHFKQRORJ\LVDQLQWHJUDOSLHFHRIODUJHVFDOHPLOLWDU\WUDLQLQJVLPXODWRUVFXUUHQWO\LQXVHWKURXJKRXWWKH -

2019 Brookings County 4-H Shooting Sports Schedule

2019 Brookings County 4-H Shooting Sports Schedule Archery - 90 min BB Gun - 60 min Air Pistol - 60 min Air Rifle - 60 min .22 Rifle - 90 min .22 Pistol - 60 min Saturday Saturday Saturday Saturday Saturday Saturday 8:00 am 8:00 am 8:00 am 8:00 am 9:30 am 8:00 am 10:10 am 9:05 am 9:05 am 9:05 am 11:00 am 10:10 am 10:10 am 10:10 am Sunday Tuesday Sunday 11:15 am 11:15 am 3:00 pm 6:00 pm 5:15 pm All 4-H Shooting Sports disciplines will be held in Brookings at the Brookings County Outdoor Adventure Center; 2810 22nd Ave South SD 4-H Shooting Sports Website Link: www.sd4-hss.com sign up state time after qualified match score Brookings County 4-H Shooting Sports Page: https://www.facebook.com/brookings4hshootingsports Brookings County 4-H: https://www.facebook.com/brookings4H Cancellation Policy: If advising no travel in Brookings County then there will be no Shooting Sports. We will also list on KELO Closeline www.keloland.com/weather/closeline.cfm and Brookings County 4-H Shooting Sports Facebook page for the cancellation. There are many practice dates so use your best judgment if conditions are questionable in your area. Coaches will also use the Remind app for communicating reminders and schedule changes. Date Event Remember: November 19 – Online Registration Open: Payment is due to the Brookings County Extension/4-H December 2 https://fairentry.com/Fair/SignIn/2599 Office by 5 pm on December 7 or spots will be released. -

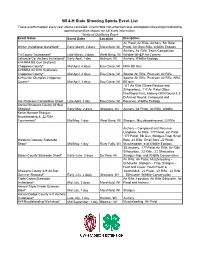

WI 4-H State Shooting Sports Event List These Events Happen Every Year Unless Cancelled

WI 4-H State Shooting Sports Event List These events happen every year unless cancelled. Check https://4h.extension.wisc.edu/opportunities/projects/shooting- sports/competitive-shoots/ for full event information. *National Qualifying Event Event Name Event Dates Location Disciplines Air Pistol, Air Rifle, Archery, Sm Bore Winter Invitational Marshfield* Early March, 2 days Marshfield, WI Pistol, Sm Bore Rifle, Wildlife Ecology Archery, Air Rifle, Team Competition, Tri-County Tournament* Late March, 2 days West Bend, WI Wildlife WHEP Art Contest Lafayette Co. Archery Invitational* Early April, 1 day Belmont, WI Archery, Wildlife Ecology 4-H NRA BB Gun Sectional Chippewa County* Mid April, 4 days Eau Claire, WI NRA BB Gun 4-H/NRA Air Rifle Sectionals Chippewa County* Mid April, 4 days Eau Claire, WI Sporter Air Rifle, Precision Air Rifle 4-H/Junior Olympics Chippewa Sporter Air Rifle, Precision Air Rifle, NRA County* Mid April, 3 days Eau Claire, WI BB gun .117 Air Rifle (Three-Position and Silhouettes), .117 Air Pistol (Slow Fire/Rapid Fire), Archery (300 Round & 3- D Animal Round, Compound and Karl Petersen Competitive Shoot Late April, 1 day Eau Claire, WI Recurve), Wildlife Ecology Annual Shawano County All Star Shootout* Early May, 2 days Shawano, WI Archery, Air Pistol, Air Rifle, Wildlife Kettle Moraine Shotgun, Muzzleloading & .22 Rifle Tournament* Mid May, 1 day West Bend, WI Shotgun, Muzzleloading and .22 Rifle Archery – Compound and Recurve- Longbow, Air Rifle .177 Pellet, Air Pistol .177 Pellet, BB Gun, Shotgun-Trap, Small Western Gateway Statewide Bore .22 Rifle, Small Bore .22 Pistol, Shoot* Mid May, 1 day River Falls, WI Muzzleloader, and Wildlife Ecology. -

September 2011 Ear Double-Alpha Members and Subscribers, D We Are Proud to Offer You This New Issue of the DAA Zone Digital Magazine

September 2011 ear Double-Alpha Members and Subscribers, D We are proud to offer you this new issue of the DAA Zone digital magazine. As always, our thanks go to all who contribute to the content. Without your support it would not be possible. Thank you so much! The World Shoot is just around the corner and everyone’s preparations are at fever pitch. It sure feels that way here at DAA. Of course, Eli and I will be com- peting in the match, but we also have several exciting DAA projects in the works in Rhodes. First - we will be making the official match DVD, and it will be our best ever! Unfortunately, it may also well be our last, as DVD sales have dropped off con- siderably in recent years. This is largely due to rampant illegal copying, which greatly reduces sales. To all of you who bought and enjoyed our productions - we thank you. Double-Alpha Zone edited and produced by We are also involved in promoting and selling an exciting new service - the pro- Double-Alpha Academy fessional match photography offered by BitMyJob. This Greek-based company ____________________________ will have several professional photographers out on the range, taking top qual- for more information ity pictures of ALL the competitors. These pictures will be available for purchase visit: online, with or without additional super-cool editing effects from www.world- www.doublealpha.biz shootphotos.com or email us at: And, in addition, we will be launching two new major products at the World [email protected] Shoot, both of which are joint ventures with our partner, CED. -

Pistol and Rifle Performance

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Pistol and Rifle Performance: Gender and Relative Age Effect Analysis Daniel Mon-López 1,* , Carlos M. Tejero-González 2 , Alfonso de la Rubia Riaza 1 and Jorge Lorenzo Calvo 1 1 Departamento de Deportes de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Actividad Física y del Deporte-INEF de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, 28040 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] (A.d.l.R.R.); [email protected] (J.L.C.) 2 Department of Physical Education, Sport and Human Movement, Autonomous University of Madrid, 28049 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-913364109 Received: 17 January 2020; Accepted: 17 February 2020; Published: 20 February 2020 Abstract: Background: The sport overrepresentation of early-born athletes within a selection year is called relative age effect (RAE). Moreover, gender performance differences depend on the sport. The main objectives of the study were to compare performances between gender and RAE in precision shooting events. Method: The results of 704 shooters who participated in the most recent World Shooting Championship were compared. Performance was analysed by event (rifle and pistol), gender and category (junior and senior), together with RAE and six ranges of ranking positions. Results: The results of the study indicated that men scored higher than women in pistol events and that no performance differences were found in rifle events when the whole group was compared. According to the birth trimester, no significant differences were found in the participant’s distribution, nor in performance in any case. Conclusions: The main conclusions of the study are: (1) the men’s pistol performance is better than the women’s even though RAE is not associated to the shooting score in any case; (2) men and women performed equally in the general analysis, but their performances were different depending on category and event with no RAE influence. -

Shooting Sports Guide

Shooting Sports Guide 2020-2021 THE PROJECT Welcome to the Adams County 4-H Shooting Sports Project! The 4-H Shooting Sports program teaches members how to safely, responsibly, and ethically use firearms while having fun. Shooting is a skill that requires self-discipline, concentration, and individual effort. It can also require considerable financial resources. Before starting this project, please talk with one of our Adams County 4-H Shooting Sports leaders to get an idea of what equipment is required for each discipline. This guide will give you information about the project, the disciplines within Shooting Sports, the project requirements, a list of the trained shooting sports leaders in Adams County, and how individuals can qualify for Adams County and State Fair shooting contests. If you have any questions, please call the 4-H office at 303-637-8100. SHOOTING SPORTS LEADERS In addition to completing all required steps of becoming a 4-H leader (outlined on the Adams County 4-H website), all leaders who work as Shooting Sports instructors are required to attend a state- sponsored training in the Shooting Sports discipline(s) they instruct. To the right are listed the key shooting sports leaders for each discipline. If you have any questions as you proceed through the 2020-2021 shooting sports project, please contact them. They are a wealth of knowledge and are happy to help you throughout your project. LEADERS .22 Rifle/.22 Pistol/Air Rifle/Air Pistol Shannon Underwood - (720) 219-5728 Please Read! Archery All Adams County 4-H Members and parents are required Mike Sager - (303) 870-9313 to sign a safety contract for every discipline in which they participate before they can start practicing.