Ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Journey Would Not Have Been Possible Without the Support of My Family, Professors and Mentors, and Frie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Interview with John Thompson: Community Activist and Community Conversation Participant

An Interview with John Thompson: Community Activist and Community Conversation Participant Interview conducted by Sharon Press1 SHARON: Thanks for letting me interview you. Let’s start with a little bit of background on John Thompson. Tell me about where you grew up. JOHN: I grew up on the south side of Chicago in a predominantly black neighborhood. I at- tended Henry O Tanner Elementary School in Chicago. I know throughout my time in Chicago, I always wanted to be a basketball player, so it went from wanting to be Dr. J to Michael Jordan, from Michael Jordan to Dennis Rodman, and from Dennis Rodman to Charles Barkley. I actu- ally thought that was the path I was gonna go, ‘cause I started getting so tall so fast at a young age. But Chicago was pretty rough and the public-school system in Chicago was pretty rough, so I come here to Minnesota, it’s like a culture shock. Different things, just different, like I don’t think there was one white person in my school in Chicago. SHARON: …and then you moved to Minnesota JOHN: I moved to Duluth Minnesota. I have five other siblings — two sisters, three brothers and I’m the baby of the family. Just recently I took on a program called Safe, and it’s a mentor- ship program for children, and I was asked, “Why would you wanna be a mentor to some of these mentees?” I said, “’Cause I was the little brother all the time.” So when I see some of the youth it was a no brainer, I’d be hypocritical not to help, ‘cause that’s how I was raised… from the butcher on the corner or my next-door neighbor, “You want me to call your mother on you?” If we got out of school early, or we had an early release, my mom would always give us instructions “You go to the neighbor’s house”, which was Miss Hollandsworth, “You go to Miss Hollandsworth’s house, and you better not give her no problems. -

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series

MCA 700 Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series: By the time the reissue series reached MCA-700, most of the ABC reissues had been accomplished in the MCA 500-600s. MCA decided that when full price albums were converted to midline prices, the albums needed a new number altogether rather than just making the administrative change. In this series, we get reissues of many MCA albums that were only one to three years old, as well as a lot of Decca reissues. Rather than pay the price for new covers and labels, most of these were just stamped with the new numbers in gold ink on the front covers, with the same jackets and labels with the old catalog numbers. MCA 700 - We All Have a Star - Wilton Felder [1981] Reissue of ABC AA 1009. We All Have A Star/I Know Who I Am/Why Believe/The Cycles Of Time//Let's Dance Together/My Name Is Love/You And Me And Ecstasy/Ride On MCA 701 - Original Voice Tracks from His Greatest Movies - W.C. Fields [1981] Reissue of MCA 2073. The Philosophy Of W.C. Fields/The "Sound" Of W.C. Fields/The Rascality Of W.C. Fields/The Chicanery Of W.C. Fields//W.C. Fields - The Braggart And Teller Of Tall Tales/The Spirit Of W.C. Fields/W.C. Fields - A Man Against Children, Motherhood, Fatherhood And Brotherhood/W.C. Fields - Creator Of Weird Names MCA 702 - Conway - Conway Twitty [1981] Reissue of MCA 3063. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Und Audiovisuellen Archive As

International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives Internationale Vereinigung der Schall- und audiovisuellen Archive Association Internationale d'Archives Sonores et Audiovisuelles (I,_ '._ • e e_ • D iasa journal • Journal of the International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives IASA • Organie de I' Association Internationale d'Archives Sonores et Audiovisuelle IASA • Zeitschchrift der Internationalen Vereinigung der Schall- und Audiovisuellen Archive IASA Editor: Chris Clark,The British Library National Sound Archive, 96 Euston Road, London NW I 2DB, UK. Fax 44 (0)20 7412 7413, e-mail [email protected] The IASA Journal is published twice a year and is sent to all members of IASA. Applications for membership of IASA should be sent to the Secretary General (see list of officers below). The annual dues are 25GBP for individual members and IOOGBP for institutional members. Back copies of the IASA Journal from 1971 are available on application. Subscriptions to the current year's issues of the IASA Journal are also available to non-members at a cost of 35GBP I 57Euros. Le IASA Journal est publie deux fois I'an etdistribue a tous les membres. Veuillez envoyer vos demandes d'adhesion au secretaire dont vous trouverez I'adresse ci-dessous. Les cotisations annuelles sont en ce moment de 25GBP pour les membres individuels et 100GBP pour les membres institutionels. Les numeros precedentes (a partir de 1971) du IASA Journal sont disponibles sur demande. Ceux qui ne sont pas membres de I'Association peuvent obtenir un abonnement du IASA Journal pour I'annee courante au coOt de 35GBP I 57 Euro. -

Zayn's Debut Album Mind of Mine out March 25

ZAYN’S DEBUT ALBUM MIND OF MINE OUT MARCH 25TH WORLDWIDE AVAILABLE FOR PRE-ORDER NOW TRACKLISTING REVEALED The track listing for ZAYN’s highly anticipated debut album MIND OF MINE has been announced. The standard edition features the following songs: 1.MiNd Of MiNdd 2.PiLlOwT4lK 3.iT’s YoU 4.BeFoUr 5.sHe 6.dRuNk 7.INTERMISSION: fLoWer 8.rEaR vIeW 9.wRoNg 10.fOoL fOr YoU 11. BoRdErz 12.tRuTh 13.lUcOzAdE 14.TiO With the deluxe edition featuring an extra four: 15. BLUE 16. BRIGHT 17. LIKE I WOULD 18. SHE DON’T LOVE ME Target will be releasing a deluxe exclusive version of ZAYN’s MIND OF MINE, which features 2 extra songs not available on the standard deluxe release: 19. DO SOMETHING GOOD 20. GOLDEN All three editions are now available for pre-order and in advance of the March 25th album release, fans will instantly receive the tracks “iT's YoU” and “PILLOWTALK” upon pre-ordering. The video for “iT's YoU” is available exclusively on Apple Music, and is directed by Ryan Hope. “PILLOWTALK,” the first single from MIND OF MINE truly cemented ZAYN as one of the most exciting solo artist of the time. Upon release, the single debuted at #1 on the Billboard Hot 100 Chart, #1 on the U.S. Digital Songs Chart, #1 on the U.K. singles sales charts, and #1 on Billboard’s On Demand Songs Chart. The video for “PILLOWTALK” has now amassed over 180 million views. Follow ZAYN Twitter: https://twitter.com/zaynmalik Instagram: http://www.instagram.com/ZAYN Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/ZAYN Spotify Artist Page: http://smarturl.it/ZAYNSpotify Website: http://www.inZAYN.com -

Environment and Children's Everyday Lives in India And

Environment and children’s everyday lives in India and England: Experiences, understandings and practices Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Catherine Louise Walker University College London (UCL) Supervised by: Professor Ann Phoenix, Thomas Coram Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education Professor Janet Boddy, Centre for Innovation in Research on Childhood and Youth, University of Sussex 1 Declaration I carried out the study presented in this thesis as a doctoral researcher on the ESRC National Centre for Research Methods node NOVELLA (Narratives of Varied Everyday Lives and Linked Approaches), and in collaboration with researchers on two research studies, Family Lives and the Environment and Young Lives. The thesis presents data that have been generated through collaborative work between myself and members of these research studies. I conducted all of the new research in children’s schools and almost all of the new interviews with children in their homes. Except where explicit attribution is made, the analyses presented in this thesis are my own. Word count (exclusive of appendices and bibliography): 79,976 words 2 Abstract In the context of heightened global concerns about resource sustainability and ‘climate change’, children are often discursively positioned as the ‘next generation’ by environmentalists and policy makers concerned with addressing ‘climate change’ and environmental degradation. This positioning serves to present a moral case for action and to assign children a unique place in the creation of more sustainable societies. In this study I critically engage with the assumptions about children’s agency underlying such positioning by considering these assumptions in relation to children’s situated narratives of environment and everyday life. -

141715236.Pdf

This issue of the Other Press has been brought to you by these people (and others) · Don't you love them so? Table Cont 28 30 , Georwe s Malady· Now if :r: could just prowam t ·his VCR to tape "Friends." - I guess it had to happen. The deli tions of its members." This is not At worst, when foisting spurious O where I go for sandwiches has a to say that he did not cherish propaganda, mission statements ~ mission statement. Posted in billboard such beliefs, only that he was too are misleading. At best, they are +-' proportions behind the counter, where busy eradicating a disease to superfluous. One local retail outlet, the menu should be, is their corporate embroider the words on a doily in a "statement of core values" C manifesto, replete with such feel-good and have them framed. issued to its employees, imparts 0 sentiments as "We recognize and But we Jive in a time when the stunning revelation, "We respect the rights of others" and "We humility and quiet accomplish recognize that profitability is · acknowledge the diversity in our ment are seen as weaknesses, essential to our success." Well, U community." The poor harried em when enterprising executroids duh. Might as well include the part C ployee making my sandwich behind buy off-the-rack personalities about opening the doors. As for the counter was so busy respecting . from Tony Robbins and other the respect-the-rights-of-others 0 rights and acknowledging diversity such snake oil salesmen, when type of statements, these are •- that he forgot the mustard. -

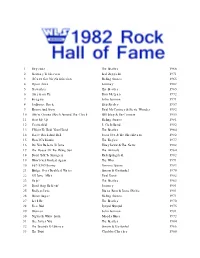

(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Open Ar

1 Hey Jude The Beatles 1968 2 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 3 (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 4 Open Arms Journey 1982 5 Yesterday The Beatles 1965 6 American Pie Don McLean 1972 7 Imagine John Lennon 1971 8 Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley 1957 9 Ebony And Ivory Paul McCartney & Stevie Wonder 1982 10 (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 11 Start Me Up Rolling Stones 1981 12 Centerfold J. Geils Band 1982 13 I Want To Hold Your Hand The Beatles 1964 14 I Love Rock And Roll Joan Jett & The Blackhearts 1982 15 Hotel California The Eagles 1977 16 Do You Believe In Love Huey Lewis & The News 1982 17 The House Of The Rising Sun The Animals 1964 18 Don't Talk To Strangers Rick Springfield 1982 19 Won't Get Fooled Again The Who 1971 20 867-5309/Jenny Tommy Tutone 1982 21 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel 1970 22 '65 Love Affair Paul Davis 1982 23 Help! The Beatles 1965 24 Don't Stop Believin' Journey 1981 25 Endless Love Diana Ross & Lionel Richie 1981 26 Brown Sugar Rolling Stones 1971 27 Let It Be The Beatles 1970 28 Free Bird Lynyrd Skynyrd 1975 29 Woman John Lennon 1981 30 Nights In White Satin Moody Blues 1972 31 She Loves You The Beatles 1964 32 The Sounds Of Silence Simon & Garfunkel 1966 33 The Twist Chubby Checker 1960 34 Jumpin' Jack Flash Rolling Stones 1968 35 Jessie's Girl Rick Springfield 1981 36 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 37 A Hard Day's Night The Beatles 1964 38 California Dreamin' The Mamas & The Papas 1966 39 Lola The Kinks 1970 40 Lights Journey 1978 41 Proud -

Botting Fred Wilson Scott Eds

The Bataille Reader Edited by Fred Botting and Scott Wilson • � Blackwell t..b Publishing Copyright © Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 1997 Introduction, apparatus, selection and arrangement copyright © Fred Botting and Scott Wilson 1997 First published 1997 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 Blackwell Publishers Ltd 108 Cowley Road Oxford OX4 IJF UK Blackwell Publishers Inc. 350 Main Street Malden, MA 02 148 USA All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form Or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any fo rm of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Ubrary. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Bataille, Georges, 1897-1962. [Selections. English. 19971 The Bataille reader I edited by Fred Botting and Scott Wilson. p. cm. -(Blackwell readers) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-631-19958-6 (hc : alk. paper). -ISBN 0-631-19959-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Philosophy. 2. Criticism. I. Botting, Fred. -

The Port Weekly SUPPORT

REPORT CARDS SUPPORT NEXT WEEK The Port Weekly RED CROSS VoL XVI—No. 7 SENIOR fflGH SCHOOL. PORT WASHINGTON. LONG ISLAND. N. Y.. FRIDAY. DECEMBER I. 1939 Price: Five CsntB Teachers Heeling 4 Committee Named Second Annual Fall Convention Discusses Port To Investigate Of Nassau County Press Group Narking System Handbook To Be Held At Adelphi College Definite Meaning Is Given G. O. Is Planning To Publish Many Well Known Newspapermen Will Speak On Wednesday, To Various Graduations Handbook For Newcomers December 6; Panel Discussion And Criticism Of Newspapers Of H. S. U About Port High School To Be Held; Banquet And Press Dance Will Close Confab The Second Annual Fall Con- A t the teachers meeting of last A t the November 21 meeting vention of the Nassau County Tuesday, which mii in rtyjm 108, of the student council a coi.iin.t- Midc h Popular Press Association will be held the present system of marking tee of three was appointed to during the afternoon and evening was discussed. The meanings of look into the possibilities of pub- m CHRISTMAS SEALS lishing a student handbook. This Noontime Activity of December 6 at Adelphi College each grade were again defined to handbook would contain informa- i n Garden City. provide for greater uniformity in tion about school in general and North Shore Symphony Plans All Nassau school newspaper the marking procedure. Fall Play To Be its extracurricular activities that To Present Concert staffs are invited to attend this I n Subject Mastery should be of interest to students convention. Christian Burckel, entering this school. -

A Piece of History

A Piece of History Theirs is one of the most distinctive and recognizable sounds in the music industry. The four-part harmonies and upbeat songs of The Oak Ridge Boys have spawned dozens of Country hits and a Number One Pop smash, earned them Grammy, Dove, CMA, and ACM awards and garnered a host of other industry and fan accolades. Every time they step before an audience, the Oaks bring four decades of charted singles, and 50 years of tradition, to a stage show widely acknowledged as among the most exciting anywhere. And each remains as enthusiastic about the process as they have ever been. “When I go on stage, I get the same feeling I had the first time I sang with The Oak Ridge Boys,” says lead singer Duane Allen. “This is the only job I've ever wanted to have.” “Like everyone else in the group,” adds bass singer extraordinaire, Richard Sterban, “I was a fan of the Oaks before I became a member. I’m still a fan of the group today. Being in The Oak Ridge Boys is the fulfillment of a lifelong dream.” The two, along with tenor Joe Bonsall and baritone William Lee Golden, comprise one of Country's truly legendary acts. Their string of hits includes the Country-Pop chart-topper Elvira, as well as Bobbie Sue, Dream On, Thank God For Kids, American Made, I Guess It Never Hurts To Hurt Sometimes, Fancy Free, Gonna Take A Lot Of River and many others. In 2009, they covered a White Stripes song, receiving accolades from Rock reviewers.